Destiny often has a hard time happening, seldom more so than in the case of Zora Arkus-Duntov, the champion of the Chevrolet Corvette. He made his way from Brussels to Detroit via Leningrad, the Russian revolution, Berlin, Nazi persecution, along an escape route through Marseilles and Lisbon to New York, eventually taking the Harley Earl-designed 1953 ’Vette under his wing and keeping it there, battling most of his life for its rightful place in American society.

His battle is the stuff of legends. The fact that the Corvette has been with us in one form or another for around 60 years and seven generations is the best testimony to that.

Born in Brussels on Christmas Day 1909, Zora was a year old when his parents, mother Rachel and father Yakov Myseivich Arkus, returned to their hometown of St. Petersburg. Deep malcontent was spreading through Russian society like a rumbling earthquake, which eventually erupted in 1917. By that time, Rachel and Yakov had divorced and a new man had entered her life, Josef Duntov. But it wasn’t until 1927 that the family moved to Berlin, where it was agreed that Zora and his brother Yura would adopt the surname Arkus-Duntov.

Zora—born Zachary—became interested in motorbikes and cars. His first machine was a 350-cc Diamant motorcycle, which he raced and used as quick urban transport on the unsuspecting streets of the German capital. After that he acquired a racing car of sorts, one of two 1922 Bob oval racers with long sloping mudguards, a low-slung pointed tail and built by an obscure manufacturer that has long since disappeared.

In 1934, Duntov received his engineering degree from Berlin’s Technical University and began writing technical papers for the prestigious magazine Auto Motor und Sport. Later, he met German Bluebell Girl dancer Elfi Wolff in Paris and the two were married just before the outbreak of the Second World War. The Arkus-Duntov brothers joined the French air force, but when France surrendered Zora obtained exit visas for Elfi, Yura and his parents from the Spanish consulate in Marseilles. Elfi, who was still living in Paris, made her escape to Bordeaux and on to the French seaport just ahead of the Nazi Blitzkrieg. Now reunited, the family made its way to Lisbon, the center of Allied and Axis intrigue, where they were able to board a ship for New York.

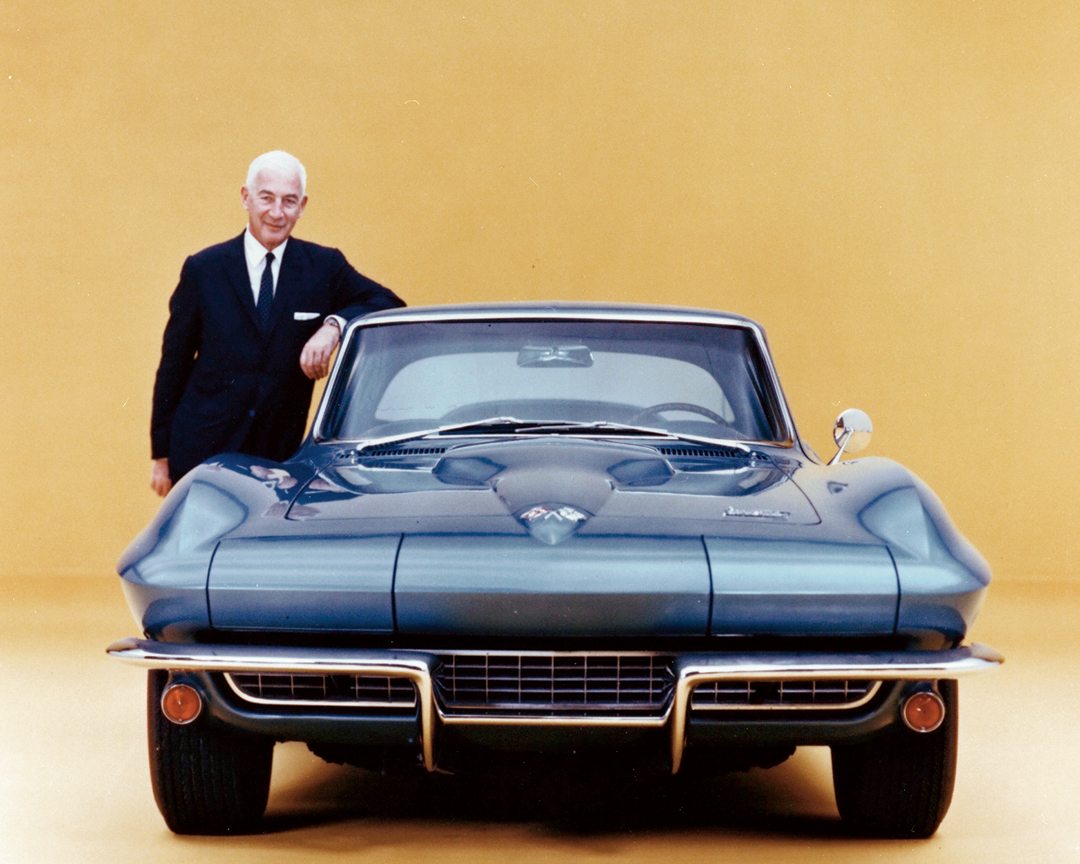

Duntov’s Corvette SS prototype racer featured a magnesium body over a tubular steel frame.

Photo: GM Media Archive

DISPLAY SETTINGS

The family settled in Manhattan and the two brothers founded Ardun—an anagram from their double-barreled surname—an engineering company that supplied mechanical equipment to the American armed forces. The company employed 300 people in its wartime heyday, which dropped to just over 20 after the hostilities. Following the war, Duntov designed his overhead valve conversion unit that promised high horsepower and torque over a wide band, but Zora was unable to further develop and build it. Later, faulty financial decisions by a partner led to Ardun’s failure. The conversion was used in racing years later, but built by others.

In both 1946 and 1947, Zora tried to qualify a Talbot Lago for the Indianapolis 500, but without success. He transferred to Britain in 1948, where he helped Sydney Allard develop his 5.4-liter Cadillac-engined J2X, two of which were entered for the 1952 24 Hours of Le Mans. Zora and Frank Curtis kept their mighty machine going for 15 hours, before it retired with brake and rear axle trouble. Paired with Englishman Ray Merrick, Duntov was even unluckier in the Le Mans a year later, when the Caddy-powered J2R faded away with engine trouble after 65 laps. But he did win his class driving a rorty little 1100-cc Porsche 550 RS Spyder in the 1954 race, in which he came 14th overall, and in the 1955 Le Mans, coming home 13th in that tragic event.

While all of that was going on, Arkus-Duntov started job hunting in the United States in 1952. He made a bee-line for General Motors after seeing a Chevrolet Corvette on a turntable at the GM Motorama in Manhattan. He joined the company in 1953 and regarded the car as visually outstanding, but was disappointed in what was inside it. So, in his passionate, opinionated way he wrote to the chief engineer of Chevrolet, Ed Cole, saying how much he would like to work on such a stunning looking car and sent a technical treatise offering an analytical way of determining the car’s top speed. That led to engineer Maurice Olley inviting him to Detroit, after which Zora started at Chevrolet as an assistant staff engineer.

Soon afterwards, Duntov wrote his famous “Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot Rodders and Chevrolet” paper, which became part of the fabric of Chevrolet and helped turn the company’s otherwise dull products into some of the most exciting and successful in the history of American motoring. Zora’s star was in the ascent, so much so that he was appointed the director of high performance. His magic turned a dull performer like the Corvette into a vibrant sports car that was a match for those of Maserati, Mercedes-Benz, Porsche and even Ferrari.

First up was a small block V8 for the Corvette in 1955 with all the extra power that brought. To prove the engine’s worth, Duntov entered a pair of Chevy 210 sedans equipped with the engine in the 1956 Pikes Peak Auto Hill Climb. On July 4th Zora personally raced it the 12.42 miles to the top in a record 17 minutes and five seconds.

That was followed by a test session at GM’s Arizona desert testing facility, where the V8 Corvette with an unconventional Duntov-designed camshaft and aero-dynamic improvements managed an astounding 163 mph, unheard of for the period. So, off Duntov and his team went to Daytona Beach. They arrived in Florida in December, but had to wait until January before they had the slightly wet sand with no tidal incursions that most suited their flying mile record attempt.

Conditions still weren’t perfect, but even so Duntov set a two-way average of 150.583 mph—he had his record.

After that, Zora Arkus-Duntov’s magic continued, with the development of his high-lift camshaft that helped bring fuel injection to the Corvette in 1957, then came four-wheel disc brakes.

Photo: GM Media Archive

In the early ’60s there was a mighty clash between Bill Mitchell, vice-president of Chevrolet design, and Zora. The battleground was the Corvette Sting Ray, show stopper of a car for the period with its incisive wedge shape and split rear window, which Duntov hated because it obstructed the driver’s view. He lost that battle; his argument was further weakened when the Sting Ray was launched and people loved it.

Duntov, however, continued to huff and puff over “his” Corvette. He said the Sting Ray ought to have its own badge that would become a sign of prestige like the Mercedes-Benz star; he fought against a move to build a four-seater Corvette; he didn’t like the Sting Ray name, either, and continued to push for just Corvette. But he was stuck with the ’Ray, so he tried to make the best possible engineering job of it, giving the car bigger brakes and a larger, stiffer frame than previous models so that weight reduction improved ride and handling.

In 1963, Duntov launched his Grand Sport program to create a special lightweight, 1800-pound model with an aluminum version of his V8 small block and special twin-spark cylinder heads. His plan was to race it on the international circuit, pitting it against the big guns of the GT class. But GM policy of the day wouldn’t let him race the Grand Sport, of which only five were built. They ended up in private hands and Duntov delighted in supporting his privateers and to hell with the official ban.

For years Duntov had wanted a mid-engined Corvette, but he had been given the thumbs down by the powers that be every time he made a new push for the concept. So, before his obligatory retirement in 1975, he designed just such a car using available parts. A squat, broad, all-business two-seater experimental car called the XP882, which made its debut on a turntable at the 1970 New York Auto Show labeled a Corvette prototype; it was the surprise hit of the event. But although the company looked briefly at transverse and two/four rotor Wankel engines with the Aerovette show car, the XP882 went no further. The production Corvette was selling too well to entertain such radical changes.

The GM bosses were certainly barking up the wrong tree if they thought Zora would shut up after his retirement. Whenever the Corvette was center stage, Zora was with it. For instance, he was at the rollout of the one millionth Corvette in 1992 and symbolically drove a bulldozer as the ground on which the National Corvette Museum was cleared in 1994. And just before he died aged 86 on April 21, 1996, Duntov was speaker of honor at “Corvette. A Celebration of an American Dream” at Cauley Chevrolet in Detroit. Of course, he stole the show.

Zora was uniquely honored when his ashes were interred at the museum. None other than Pulitzer Prize winner George Will wrote in his Arkus-Duntov obituary headed “Born to be an American:” “If you…do not mourn his passing, you are not a good American.”