1972 Lola T290-Tecno

Here is your first question for 10 points: How many racing car manufacturers have been going nonstop for 50 years? Answer: two. Let me refine the question a bit. How many manufacturers of only racing cars have been going for 50 years and are still in international competition? Answer: one.

By the time you read this, Lola will have been at Daytona and Sebring for the big sports car events of the year at those tracks, and given the seriousness of effort in Huntingdon, UK, they should have done well.

Beginnings

Eric Broadley established Lola Cars in 1958 after building a 1,172-cc, Ford-engined Broadley Special for what was known in England as the Ford Ten Special class. The little “clubmans” car was successful from the outset and quickly led to the development of a Coventry Climax-powered variant. Eric shared the driving of the early cars with his cousin Graham, but Eric felt the new car was too quick for himself, so he decided to concentrate on design and construction, as well as with the formation of Lola Cars Ltd. The Climax-powered car became the prototype of the Lola Mk I. Thirty-five examples of the Mk I were built during a 4-year period; most of the multitubular space frames had Climax engines and were built in the Lola premises at Bromley, in Kent. The Mk I was a very successful challenger to Lotus and Elva, with Peter Ashdown winning many races in his car, and Lola taking its first European victory at Clermont-Ferrand in France.

Broadley ventured into single-seaters in 1960 with a front-engined Formula Junior, which struggled to compete with the dominant Lotus and Coopers. A rear-engine Junior followed, but it still couldn’t get on terms with the Colin Chapman and John Cooper products. However, when the Lola MK 5 and MK 5a appeared in 1963, the car was much more promising, and Richard Attwood won the 1963 Monaco Junior race supporting the Grand Prix. For 1962, Reg Parnell had commissioned a Grand Prix car, for which John Surtees and Roy Salvadori were to be the drivers. Surtees put the Mk 4 on pole at Zandvoort and was 2nd in the British and German Grands Prix.

This was a hugely busy period for Broadley, having already been in minor and major formulae when his partnership with Ford saw the Mk 6 GT sports car with the 4.2-liter Ford engine go to Le Mans in 1963. This effort prompted Ford to sign an agreement with Broadley to develop the MK 6, which eventually became the amazingly successful Ford GT40. Sports car racing in its various forms became increasingly important for Lola. As such, Broadley produced the T-70 in both open Mk 2 form, and the lovely Mk IIIB coupe. Big-banger Lolas won in Can-Am, British and European races, and are still among the most popular cars for drivers and spectators alike in today’s historic events.

USAC and Indy cars followed the T-70, with Graham Hill winning the Indy 500 in 1966, at a time when Lola was very active in F2 with BMW and Cosworth engines, and had also begun to gain prominence on the European F3 scene, with drivers such as Nigel Mansell and Arie Luyendijk.

In 1970, Lola moved to its current premises at Huntingdon, where it went on to produce a wide variety of purpose-built racecars including F5000s and a unique series of 2-liter sports racers.

The T290

Sports car racing was always important to Eric Broadley, sports cars being Eric’s roots in racing. Derek Bennett’s Chevrons had been doing well in the clubman and GT classes, but when the 2-liter sports car classes began in international racing, Broadley’s new open monocoque T210 took Chevron by surprise resulting in Jo Bonnier winning the 2-liter title in 1970. Helmut Marko repeated the feat in 1971 with the 210’s successor the T212, giving Lola the manufacturers’ crown as well.

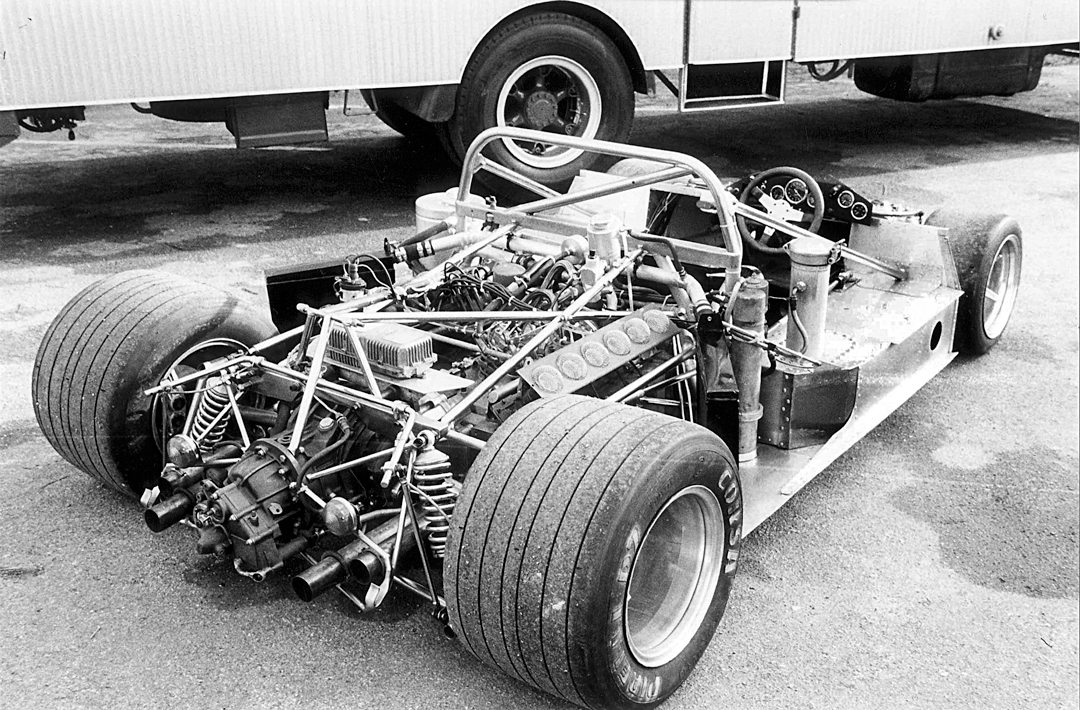

The T280 and the T290 both appeared in 1972. By now Broadley and Bob Marston were joined in the design work by Patrick Head and John Barnard, which was a truly formidable team. The T280 and T290 were similar cars, the 280 built to receive the 3-liter Cosworth V-8 and the 290 for 2-liter racing, though, as you will see, our test car had a slightly different history, being a 290 with a 3-liter engine. The T280 was never entirely successful, but it frightened the big teams on a number of occasions, and had it been a bit more reliable would certainly have won several races.

Over the next 10 years, the T290 spawned the T292, 294, 296, 297, 298, and 299, as Lola worked hard to stay on top in 2-liter racing. Many of the cars were updates of the previous models, using the earlier chassis, while a number were built with brand-new chassis for customers around the world.

Photo: Peter Collins

I was fortunate enough during my short dabble in the World Sports Car Championship in the early 1970s to have raced against the Lola T210, T212, and then the T290 and its later variations. I was even luckier to know—and still know—Tony Birchenough who started in sports cars in a Chevron B8, and then had a T212 and then the T290, which he still has in his possession, chassis HU 22. This car did long-distance races for many years, and has come back on the scene to run at the Le Mans Classic. Tony shared the driving with Brian Joscelyn among several others. I went with Tony’s Dorset Racing team to a number of races in 1974, including the three races in Angola. HU 22 was probably the Lola with the longest and most consistent international competition record.

HU 4—T290 and Tecno

Italian Lorenzo Prandina is a great guy, humorous, generous and passionate about Italian cars…especially the obscure, the rare, and the downright crazy. He owns and is restoring the Life Grand Prix car, arguably the least successful GP car of all time. It never qualified, it never prequalified, and I don’t think it ever made a complete lap of a circuit. Its W-12 engine was a nightmare, and F3 cars at the time were faster…but what a challenge! Prandina owns a beautiful Tecno PA123 F1 car and the 1972 Ferrari 312B3 “Spazzaneve”—the snow-shovel!

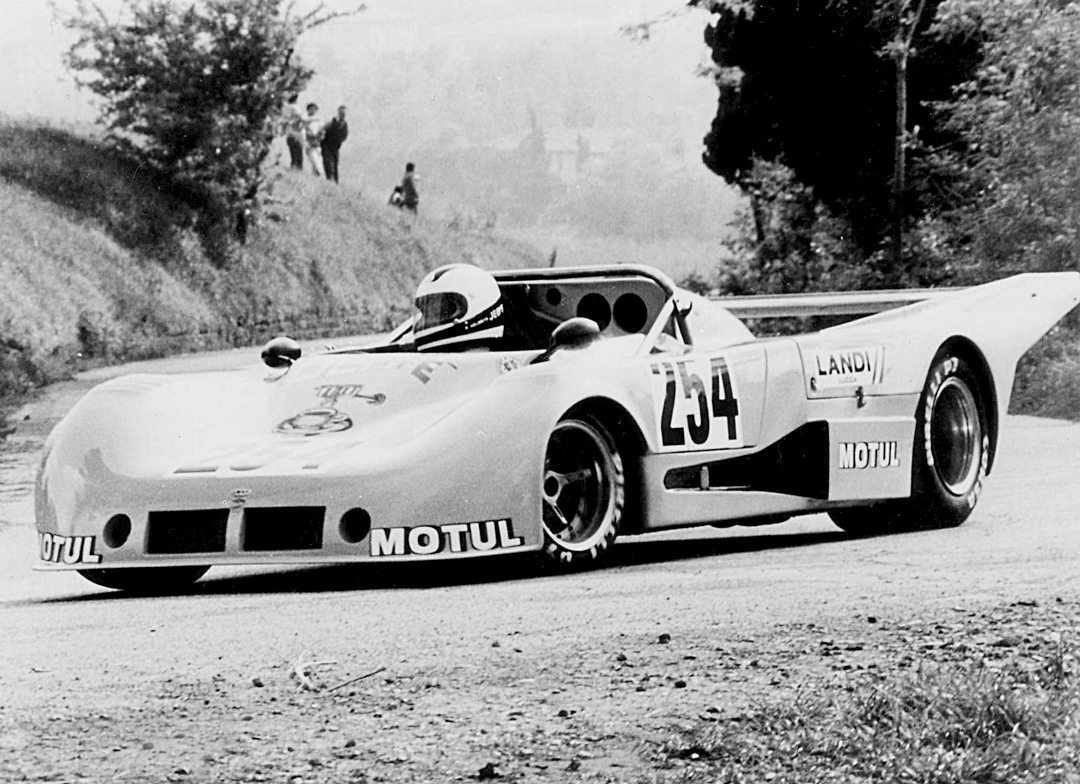

Lorenzo agreed to bring HU 4 to the Silver Flag Hill Climb in Italy, the 9-kilometer historic hillclimb event near Piacenza, which runs on public roads from Castell Arquato up the mountain to the hilltop town of Vernasca. The Silver Flag always attracts fabulous and little-known cars, and is now as famous for its wonderful social atmosphere as for the cars.

This car was built as a standard T290 in 1972 and was sold to Jo Bonnier, who in addition to being a Grand Prix driver and competitive sports car pilot, was the Lola importer in Switzerland. His yellow-and-red T70, T210, 212, and 280s were very well known around Europe. Sadly, Bonnier was killed at Le Mans in that same year when his T280-DFV touched another car and crashed into the trees at high speed.

HU 4 went to Bonnier painted in red and complete with a 2-liter Cosworth FVC engine. The FVC was in common use by the long-distance racers of the period. It was flexible, pretty reliable and churned out a respectable amount of power—somewhere between 230 bhp and 275 bhp. I raced Tony Goodwin’s Dulon with an FVC and found it a superb unit, especially for a long-distance beginner, as it had no serious quirks and a pretty wide power band unlike its predecessor, the FVA. Interestingly, rather little is known of what happened to the car in the 2–3 years after Bonnier’s death.

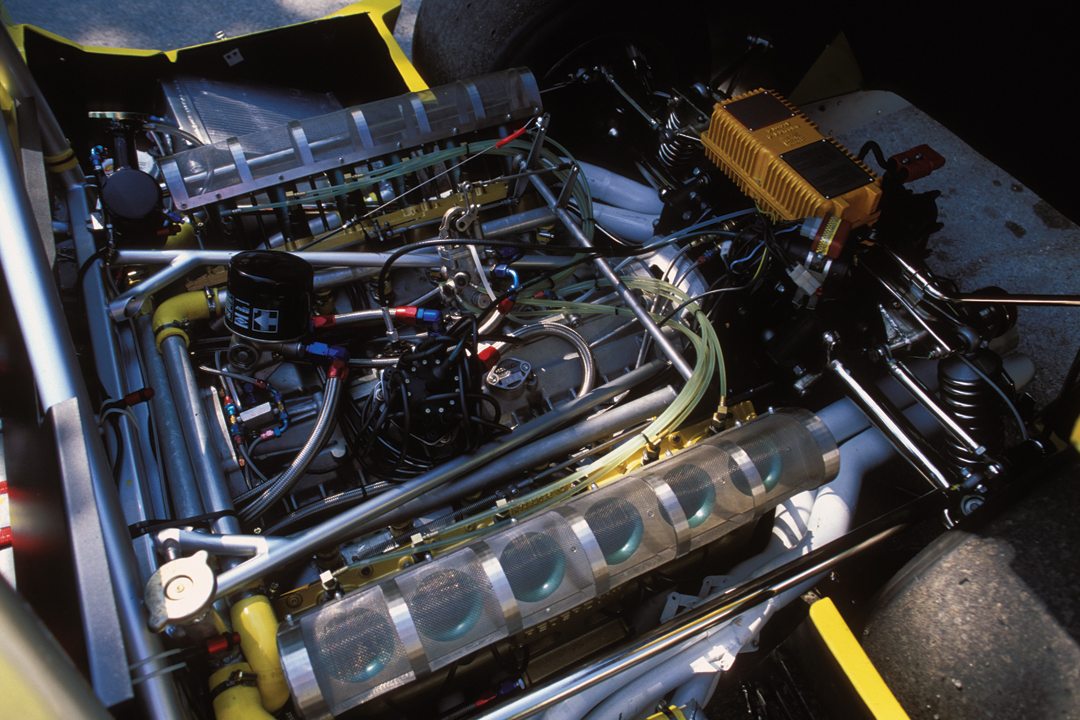

In late 1975 or early 1976, HU 4 changed hands and arrived with its new owner, Sergio Mingotti, in Italy. Mingotti had been a mechanic with the Pederzani brothers who built and raced Tecnos. It did some hillclimbs in Sicily, driven for Mingotti by a Signor Bono, using the original 2-liter engine. While there are some arguments about the exact timing of the next move, it appears the car was sold to a Signor Paganucci in 1979. Paganucci had Francesco Landi turn the T290 into something quite remarkable. Landi, who with his son Giovanni, still runs Landi Motors, which specializes in bodywork, chassis, and engine restoration and rebuilds historic racecars, had in his possession one of the original Tecno, 3-liter, Flat-12 Grand Prix engines. Luciano Pederzani had apparently given it to the senior Landi in appreciation of Landi’s good work in running a Ford-engined Tecno F2 car in hillclimbing the previous season.

The T290 chassis required some adaptation to fit the Tecno F1 unit, as this engine is a fair bit wider and heavier than a 2-liter motor. The midsection of the monocoque was lengthened and strengthened, and some changes were made to the bodywork. Additionally, the nose was shortened to make the car more suitable for use on hillclimbs. Paganucci and his brother ran the car in several Italian hillclimbs between the time he bought it and 1985, namely the Caprino-Spiazzi where it ran a number of times, the glorious Tecno Flat-12 being guaranteed to bring in the crowds. The Paganuccis were not renowned as great drivers, but the car was always spectacular. Painted in bright yellow by Paganucci, it was dubbed the “Yellow Screamer”…not surprisingly!

Climbing with HU 4

Photo: Lorenzo Prandina Collection

It was with great anticipation and no small degree of trepidation that I approached the task of taking Lorenzo Prandina’s pristine machine up the long Silver Flag hill. It is, in the spirit of European hillclimbs, long and challenging. I had competed here before, most memorably in the Lancia D50 and also in a Maserati Tipo 63 Birdcage, so I knew the course and also just how tricky it was if you really wanted to push it.

Silver Flag starts on the narrow main road in Castell Arquato, down at the bottom of the Val D’Arda alongside the River Arda, where a huge and enthusiastic crowd gathers for the first 100 meters after the start. The road bends right and runs 4 kilometers over a very fast series of bends, with three 20-mph chicanes put in to keep the overall speed down. After the final chicane you enter the next town, Lugagnano, do a 90-degree left past the bus stop, again with big crowds in attendance, “fly” one half mile downhill (!) over a bridge, and then start the serious uphill set of hard twists and turns, working all the way to the finish at Vernasca.

Prandina was doing the first run on Saturday morning. The conditions were good and I would have a run after lunch. Prandina’s loyal and ever-friendly mechanic worked to get the Flat-12 to run smoothly. Work had been done on the engine when it was originally put into the car to make it suitable for life as a hillclimb machine. The original F1 engines—this is #14—produced its maximum 445 bhp between 9,000 and 12,800 rpm. This unit had been tuned to bring the power band into operation between 6,000 and 11,000 rpm. The Lola T290 and its variants had several rear wing types fitted over the years, and this car has a rather flat and long wing. The Tecno engine sits quite low in the chassis giving a low center of gravity, and the airflow over the body is smooth and untroubled by bumps and bits protruding out. That is important for rear-end grip with this car.

Well, Lorenzo did his run, or part of it and the car broke. Specifically, the right rear driveshaft fractured under acceleration. The car is very low-geared for hillclimbing and there is terrific torque. I had been loaned Gianni Codiferro’s 1928 Salmson for a run—there’s another good story coming!—so I had gone up the hill and was at the top when I heard the news that the Lola had broken and there was no spare driveshaft. So, as sometimes happens, that was that. I stayed up after lunch and was on the hill to take some photos in the afternoon when the local police arrived with Prandina to say that the car had been repaired and I had to hurry and get in it. This was pretty amazing as there was no way they could have just found a driveshaft. I was rushed to and inserted into the car for my drive, with no one telling me how repairs had been achieved. I decided not to think about that!

Having sat in the car earlier and being a good bit shorter than Lorenzo, I had the foresight to grab a cushion to give me the ability to see out of the car. The racing seat is very much on an angle and, in hillclimbing, you want to see exactly where the corners are, where the apex is, where there are bumps and holes and rocks. Having done that, learned all the switches, and got a feel for what the 5-speed Hewland BTG400 required, I pressed the starter and let the clutch out…and stalled! Three times! Prandina helpfully shouted across the road to give it a lot more revs, so I booted it to 6,000 and let the clutch go, and this time she moved away. Having been parked on the side of the road instead of in the paddock so I wouldn’t get blocked in, the police then cleared the way as I soared out onto the public highway… Get that…a police escort to drive as fast as you bloody can on a public road! Only in Italy.

The ripping sound crashes into the air and instantly you can sense the spectators move to watch, to find out where that noise is coming from. We worked out over the weekend that you could hear the Tecno engine from 6 kilometers away. Throttle response is instant, the offset pedal needing very little pressure to raise the revs. However, it did need careful handling. The Hewland 5-speed box is characteristically a bit of a handful, but this one seemed even a bit more heavy than usual, but mainly in first and second, at low speed. Once under way, provided you are positive and quick, it all works well. Off the mark in first, the low gearing brings the revs right up so it’s a fast move forward and right for second and equally quickly back for third. Top gear on the fastest part of the straight was probably 150 mph, but my attention was very much on going down the box and keeping it all in a straight line for the first bout of heavy braking. The big, vented Girling discs did a good job, with plenty of feel and no sloppiness, the Avon slicks warm enough to get some good grip.

Performance in hill climbing is about precision more than anything else. You don’t get two, three, or four laps to get in a groove and ease your way in. If you want to win, or even do well, you have to be “on it” every inch of the way. Fortunately, I guess, the Silver Flag is not timed, so you can go for it, take it easy, or even carry a passenger. This may be a relief for some, but I really wanted to see what this car would do. The torque was stunning up through the gears—that was with low gearing and it would have been the same with high gearing, as long as you got to 6,000 and that wasn’t hard. For all the problems the F1 Tecno had in period, this engine ran beautifully. I came into Lugagnano a bit too quickly, too many revs in third, down to second, and a really hard foot on the brakes. The tail wiggled…a bit…but it all held together, snapped around the 90-degree corner, and was away in a yellow flash, Flat-12 symphony ricocheting off the walls of the houses, a wave from the inmates of the bar on the corner.

On the “hill proper”…left, right, left, right, negative camber, dipping, second gear, short blast, third, second, brake, go…again and again for four and a half kilometers. The cockpit is spacious, enough for elbows to fly free, though most of the work is in the wrists, often one-handed as you change gear again and again…yes, that’s 445 bhp being driven one-handed, twirling the wheel, stabbing the brake, left-foot braking and squeezing the throttle, almost at the same time. At least on a hill you don’t have to look in the mirror.

I really would have liked time to think what the suspension was doing. The impression was of a nice sense of balance, some—enough–feel but really tight, no roll at all, and neutral steering. The Landi team, still looking after this car, have got it working very well for a hillclimb car. And this hill, which is amazingly contrasting, with long, fast stretches in fourth and fifth and then miles in second and third, seemed to bring the best out of the beast. The handling was confidence inspiring. The steering is very positive with 1.4 turns lock to lock…very manageable. What was hard to get from inside the car was a sense of what it looked like tackling this bumpy and tough road, though the faces on the side reflected how it struck them. Huge grins are of epidemic proportion on Italian road events, and this was no exception. You have to resist the temptation to wave back. One hand is hard enough, but no hands?

We had the additional treat of driving the Lola-Tecno down the hill, so that provided the space to think about what was happening. The car was just amazing in short, sharp bursts, a crescendo of noise and instant acceleration, a high-pitched whine on the over-run. The car tucks neatly into tight corners both up- and downhill, no scrabbling for grip, it’s just there, and it flies out of these corners. The medium and faster bends required more caution, as the speed built very rapidly and the crowned road into a 100-mph corner was slightly unnerving. But the car stuck. In fact, it behaved supremely well, oil pressure and temperature remaining steady, and not a sign of problems in the drive department. So what was that about?

Back down in the confines of the shaded and atmospheric paddock, once I came down as well, I asked what had happened in the morning. There was a lot of laughing and shuffling of feet. I don’t think they wanted to tell me but, eventually, Lorenzo’s mechanic was too proud of what he had done not to show me. Lifting the impressive and shapely rear tail section, the Flat-12 crackling as it cooled down, he pointed to the right rear driveshaft. It had clearly been welded back together… But how? He then took me to the side of the road and pointed to a sign indicating “Disabled parking only.” This sign was some 8 inches shorter than all the other signs in the area. He had hacksawed off a section of the heavy steel signpost and cut it to fit and welded it back in place. The welding was beautifully neat, the dimensions perfect, and a disabled parking sign had helped the “Yellow Screamer” to live again. When Claudio Casale, the bubbling Silver Flag organizer, realized what had happened, he didn’t know whether to hide from the local officials or award the ingenuity prize to the team. He had no worries with the police. They would have helped to chop up the public amenities if it meant letting the car have another run.

Owning and Running a Lola T290

This is a one-off car…not an ordinary or run-of-the-mill 2-liter T290. It’s very special. There is a 2-liter on the market at the moment for $150,000, which seems pretty reasonable for a car with a sound history and in good condition. How do you put a price on this very special car? No one seemed easily able to do that, but I would guess it to be worth maybe twice that figure. It would be interesting to see this car in some circuit races, with the gear ratios raised.

The Tecno engine is beautiful, a work of art, but pretty complex, so there are few people with the knowledge and experience to run it…at least outside Italy. Interesting that Prandina runs an F1 car and fellow Italian Giuseppe Bianchini runs another one. Having said that, historic racers have gotten more exotic cars racing successfully all around the world. The Lola part of the car is straightforward, well put together, strong, not overly complex, and a great racing machine now as it was in the 1970s.

Happy 50th Birthday Lola!!

Specifications

Weight: 1,484 lbs.

Engine: Flat-12 Tecno F1

Displacement: 2995 cc

Compression ratio: 12.6 : 1

Power: 445 bhp at 11,000 rpm

Ignition and fuel: Marelli/Lucas

Gearbox: 5-speed Hewland BTG400

Drive: Rear-wheel drive

0 to 60 mph: 2.7 seconds approx.

Top speed: 180 mph

Brakes: 4 ventilated discs with Girling Competition calipers

Wheels and tires: 9” x 13” front and 13” x 13” 3-piece peg drive wheels by BBS with Avon slicks 9/20-13 front and 13/23-13 rear

Resources

I am very grateful to Lorenzo Prandina for being so helpful and especially his very resourceful team.