Harris-Costin Protos F2

Many of the drivers who progressed through the standard single-seater stages of racing in Europe in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s recall Formula 2 as the most enjoyable part of their racing careers. The cars were fast, they brought out the best in the drivers, and the driver’s skill really counted when it came to results. True, it was a dangerous category, but the racing was invariably close, the fans loved it, and the atmosphere was friendly with less commercial pressure than was present in F1 racing.

Formula 2 goes back as far as 1948, but a “proper” series for it didn’t really exist until the European F2 Championship was created in 1967. It then ran for 18 years (over 210 races) with a vast number of important drivers taking part. From 1966 until 1971, the rules called for 1600 cc racing engines; from 1972 to 1975 it was for 2000 cc production-based engines; and finally, from 1976 until 1984, the rules specified 2000 cc racing engines with a maximum of six cylinders. March chassis dominate the list of successes, but Brabham, Ralt, Matra and Martini all had their day, powered by BMW, Cosworth FVA, Ford BDA, Hart 420R and Honda engines. F2 was a class for creative imagination – a class for making small engines, push lightweight chassis to high speeds.

Enter the Protos

The story of the F2 Protos is full of coincidences and accidents of timing, and has as many connections with aviation as it does with motor racing. A youngish Brian Hart (of later Hart F2 and F1 racing engine fame) had been racing a Lotus 35 in the one-liter F2 races in 1965 and 1966 and was looking for something interesting to drive in the following season. The new rules had been announced well in advance and Hart, always an innovator, wanted something that could really exploit the new rules. Hart had started racing in the late 1950s and by 1963 had won the prestigious Grovewood Award for promising up-and-coming drivers. He had driven for the Peter Sellers team and also for Colin Chapman. In addition to his driving prowess, he also had an engineering apprenticeship at de Havilland Aircraft to his credit and had worked for Cosworth in its early days.

Costin and Hart talked about how little thought had been given to aerodynamic application in single-seater racing, and this propelled Hart into introducing Costin to Ron Harris, a great racing enthusiast and entrant who harbored a keen interest in building and running his own cars. The consequence of the meeting organized by Hart was the commissioning of four wooden F2 chassis to be built for the 1967 season, with Firestone Tires agreeing to pay part of the development costs if the team would run the entire championship season.

With less than three months before the start of the 1967 season, Costin and the Harris team had precious little time to design and build a pair of racecars that featured a timber-skinned monocoque, which was both strong and light in weight and would have advanced characteristics for air penetration. The car would have to meet the new minimum weight limit of 925 pounds and would use the Cosworth FVA 1600 cc engine, which was able to produce some 200+ horsepower.

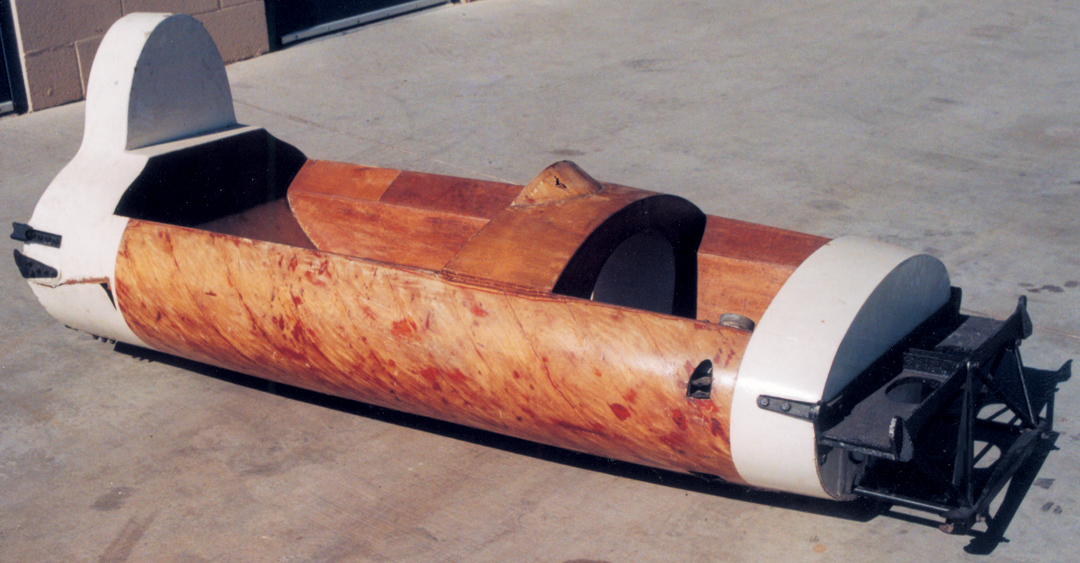

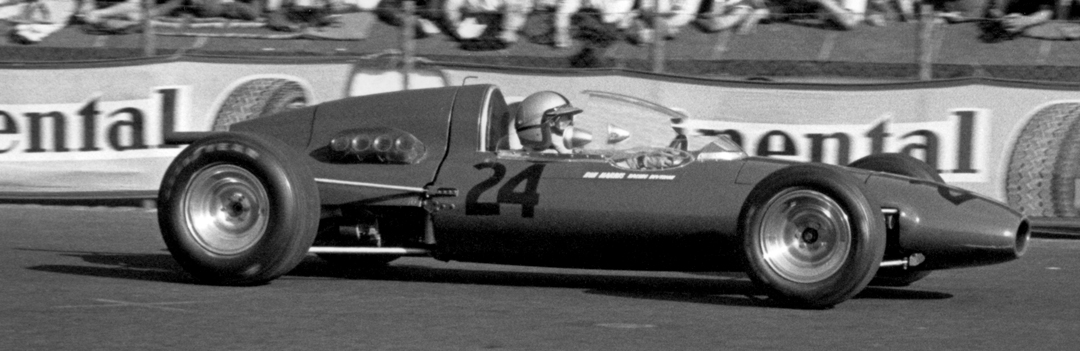

Photo: Whittlesea Collection

Costin’s original intention was to have one set of plywood panels bonded to elliptical plywood end panels and bulkheads with adhesives and further stress-bearing panels of spruce made to form strong box shapes on both sides of the cockpit area. Then, further layers of overlapping strips would form the outer skin. Much like modern carbon-fiber construction, Costin intended for the whole monocoque unit to be placed into a rubber tube to clamp the adhesive and form the proper shape, with the air being sucked out by vacuum. The outcome, Costin reasoned, would be very high levels of strength and low weight in a smooth shape. Unfortunately, the old specter of time rushing by meant this elaborate process just wouldn’t be possible. So birch plies were used for the outer skin, and the whole thing was clamped in the conventional manner and the finished wooden structure smooth-sanded when the glue was dry! Unfortunately, this speeded-up process added some weight to the finished monocoque. But after priming and a pretty coat of red paint, it was hard to tell the difference between this and a steel or alloy unit. Due to the car’s novel construction and the techniques used, Harris dubbed the car “Protos” – meaning “first” in Greek.

The unique nature of the wooden design demanded other innovations. The threat of fire in a wooden tub was a concern. This prompted Costin to design neoprene-coated alloy fuel tanks, which would be housed on fairly fragile wooden bearers within the tub sides. In the event of a serious accident, the tanks would break away from the vehicle. This idea proved to be quite effective.

Photo: Casey Annis

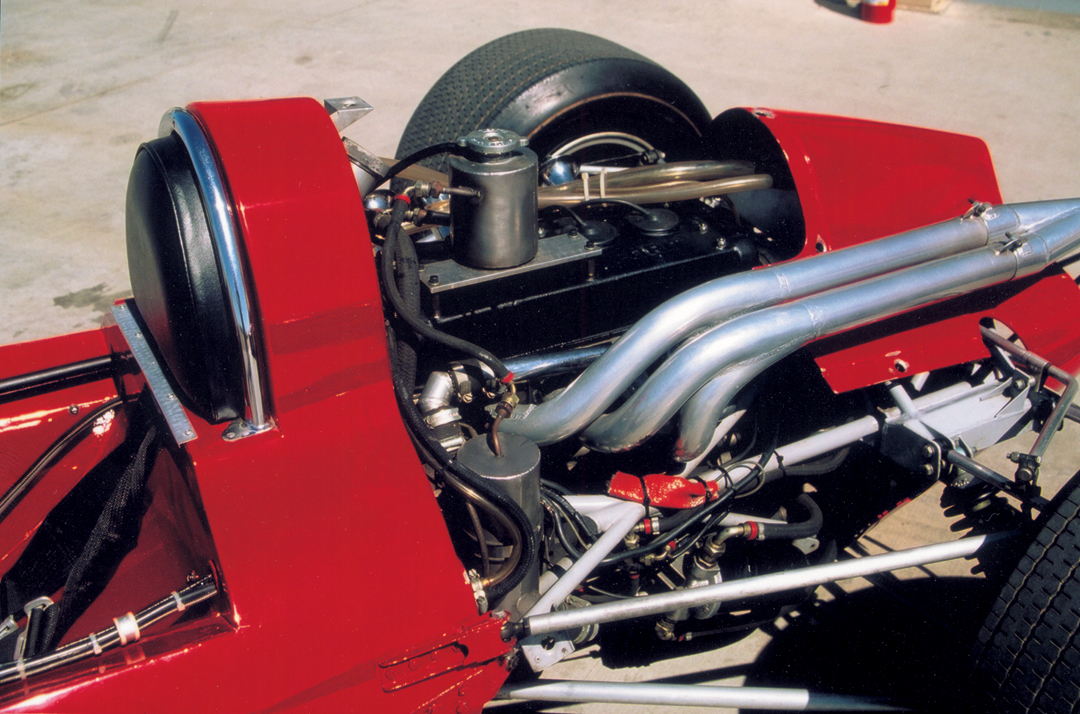

Fortunately for VRJ, our test car’s current owner, Brian Blain, brought along the spare monocoque for us to examine in detail the means by which the suspension would be attached to the tub. Keeping in mind Costin’s obsession with both lightness and aerodynamic efficiency, close examination reveals elliptically shaped front wishbones and swept-back rocker arms to improve airflow and minimize resistance. Magnesium was used, wherever possible, especially in the uprights. A magnesium bar is mounted across the front of the monocoque in conjunction with a light tubular subframe to support the dampers and rocker arms. A triangulated tube space frame at the rear carries the engine and the Hewland FT-200 gearbox. A mere six bolts hold the rear end mechanicals onto the tub, but the load is spread through the wooden monocoque via the ingenious use of internally glued metal spreaders. Particular attention was paid, throughout the building process, to the location of all components to ensure aerodynamic efficiency, and this is aided by the fairly short wheelbase of 7’10” and a wide track of five feet. The body shape is clean and has a penetrating nose with a minimum of extraneous pieces out in the airstream. The central section of the monocoque, of course, is the main part of the body, with a fiberglass nose section and an alloy rear cover, with other smaller alloy panels allowing access to the pedals.

But perhaps the most striking feature, which made the Protos stand out wherever it went, was the addition of a shapely Plexiglas canopy bubble that almost covered the entire cockpit area. This aerodynamic “bubble” was carried on a removable double-skinned wooded cockpit surround and had a 1 1/2” slot cut horizontally into it for undistorted vision. While the standard explanation of the slot was to avoid visual distortion for the driver, Costin soon concluded that allowing air into the front of the canopy and out through the top was also aerodynamically more efficient.

Protos On-Track

Photo: Casey Annis

There was hardly any time for testing once the four tubs were completed, and two of these were being built up into complete cars. Brian Hart ran a test at Goodwood and put in some very promising times but had difficulty shifting, so the canopy received the addition of a further bubble allowing greater access to the gear lever. There were also initial problems with the nose rising on acceleration and causing the front end to understeer, but this was corrected with some roll bar adjustments and better springing. This first car was chassis HCP-1 – the HCP referring to Harris Costin Protos.

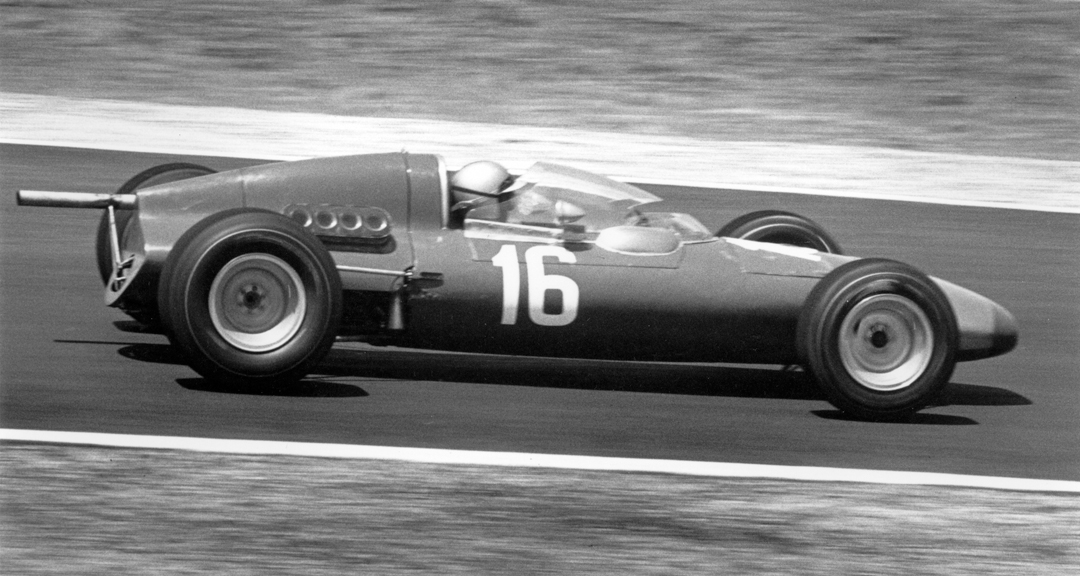

Hart brought the car to the line for its first race start at Silverstone on March 27, 1967, for the BARC Wills Trophy, where he appeared in 16th spot on the grid alongside the Lola of Jo Siffert. Hart and the HCP-1 retired in Heat 1 when a fuel pump belt broke, while a misfire appeared in Heat 2 (this misfire would cause problems for the team most of the season.) Although Harris entered two cars at Pau in France, the team wasn’t ready and gave this race a miss so they could field two cars at Barcelona on April 9. However, there was still plenty of work to do so only Frenchman Eric Offenstadt went to the Spanish race. After several off-course excursions, he retired with brake and more misfire problems. Just two weeks later, Offenstadt did little to improve the Protos image when he took Graham Hill off in practice at the Nurburgring and non-started.

Photo: Casey Annis

The second car, HCP-2, was finished and tested by Hart. Although the misfire would come and go, improvements were made in the handling, so both cars could be taken to Mallory Park on May 14. In spite of Hart’s 5th spot in practice, both cars were withdrawn from the race after Costin found a crack in an upright following yet another shunt by Offenstadt. New uprights subsequently appeared on both cars, and Hart tested HCP-2 at Brands Hatch, where the misfire appeared to have been cured. Two cars went to Crystal Palace on May 29. There, they both showed well in practice and in the heats until the misfire returned. However, Hart had managed to get up as high as third before an engine mount broke in the final. As a result, a number of modifications, mainly strengthening, took place in the following weeks, though both drivers reported the chassis to be immensely stiff.

The Protos’ potential seemed to be realized when Brian Hart put his car on pole position for the Rhein-Pokalrennen at Hockenheim on June 11. Hart held the lead (with Offenstadt back in 7th), fell back to third and then got back into the lead before the dreaded misfire returned. He eventually finished fourth, having reached a top speed of 163 mph without a tow and 172 with one! The team was much bolstered by the Protos’ high-speed capability at Hockenheim and so worked on refining the car’s top speed potential in preparation for another high-speed race at Reims on June 25. One of the more noticeable modifications was the extension of the cockpit canopy all the way back to the roll-over bar.

Practice at Reims was marred by a number of problems including Offenstadt crashing again on lap 7. Some of these problems stemmed from the fact that one of the sponsors hadn’t paid some bills, so there wasn’t the funding for bigger brakes – a real limitation at Reims. Nevertheless, Hart and the Protos amazed everyone with the car’s speed, catching and passing Jim Clark and Jackie Oliver after a spin. The French crowds cheered as Hart would drop back under braking and then catch and retake the leaders. Unfortunately, a water pipe broke on lap 37 and the over-heated engine quit, but the car was clearly the fastest of all the F2 machines on the day.

After causing the team too much grief, Offenstadt was replaced in time for the second Hockenheim race on July 9, by the small and very quick Mexican, Pedro Rodriguez. Other changes included new front and rear subframes, bigger brakes, and on Rodriguez’s car (HCP-1) a more enclosed rear body section. Rodriguez turned a third place qualifying position in practice into the lead in Heat 1, but spun when the Protos jumped out of gear and ultimately finished fourth behind Hart. The Mexican led once more in Heat 2, spun again, and then retired with a bent wishbone. Hart, on the other hand, drove an inspired race, battling with Jackie Ickx and Frank Gardner, and ultimately finished second overall and had fastest lap.

Hart retired his car at Jarama on July 23 with overheating and Rodriguez was seventh. Hart was sixth at Zandvoort on July 30, as Rob Slotemaker stood in for Rodriguez, who was doing Grand Prix duty in his Cooper-Maserati, but the Dutchman retired. Kurt Ahrens was in HCP-1 for the F2 class in the German Grand Prix at Nurburgring and retired, while Hart finished 4th in class.

Photo: Jim Gleave

On August 20, the Enna race in Sicily turned out to be the last race of the season for the Protos team. Pedro Rodriguez was back in HCP-1 and was on good form. In a recent interview, Jean Pierre Beltoise told the author how he had been surprised by the speed of the Protos. When Rodriguez attempted to get past the Frenchman’s Matra, Beltoise admitted not being ready for the move and didn’t give Rodriguez enough room. What followed was the truest test of the wooden monocoque’s strength and Costin’s safety features as the car careened out of control, hit the guardrails and broke in half, jettisoning the fuel cells as intended. The tub bore the brunt of the impact and protected the Mexican from grievous injury and was actually still in 2nd place as it hurtled past the finish line, shedding parts into Enna’s snake-infested lake! The twisted steering wheel from HCP-1 is now mounted as a prized collector’s item! Teammate Hart finished 8th in both heats and 8th overall, with the two cars reaching 165 mph on the long Enna straights.

Harris had the cars entered at Brands Hatch for August 28, but the damage and short engine supply led him to end the season early. As no more than two complete cars had existed at any one time, HCP-1 was rebuilt over the winter with a spare tub. It had been Harris and Costin’s intent to run an improved version of the Protos in 1968, but the year had been expensive, so Harris opted to run Tecnos the following year instead. However, these were delivered late and Pedro Rodriguez pressed Harris to send the Protos to the Nurburgring on April 21, this being the rebuilt HCP-1, while HCP-2 went for Vic Elford for his single-seater debut. Rodriguez retired and Elford finished seventh. Though the cars were entered for Zolder a week later, they never appeared on the F2 scene again.

Driving the Protos HCP-1

The 1968 season was so expensive and difficult for Harris that it really ended his active involvement in racing. Much of his equipment disappeared or was damaged on the late season Temporada tour in South America, so in the end everything was sold off. Englishman Richard Whittlesea bought the two cars, which comprised HCP-1 complete and HCP-2 as a rolling chassis in need of restoration. HCP-1 was fettled by Whittlesea, an accomplished engineer himself, and saw some limited action in the mid-1980s while it was on loan to the Donington Collection. The cars were then sold with the surviving spare tub to American Norbert McNamara, who had raced a Costin sports car in the USA. Blain bought HCP-2 in 1988 as a rolling chassis, and an FVA and Hewland FT 200 gearbox were found in California. He finally bought HCP-1 much more recently, and with the spare tub, owns virtually all that remains of the Ron Harris Protos Team.

While Blain is now completing the rebuild of HCP-2, HCP-1 remains in the condition it has been in since the 1970s, when it had a mild restoration by Whittlesea. The engine has had some tuning and tidying up, but essentially this car is very much like it was when Rodriguez drove it at Hockenheim in April 1968. For our test drive, Blain first did a few laps without the cockpit surround (just to make sure nothing would fall off), and then I was sent out with the canopy in place.

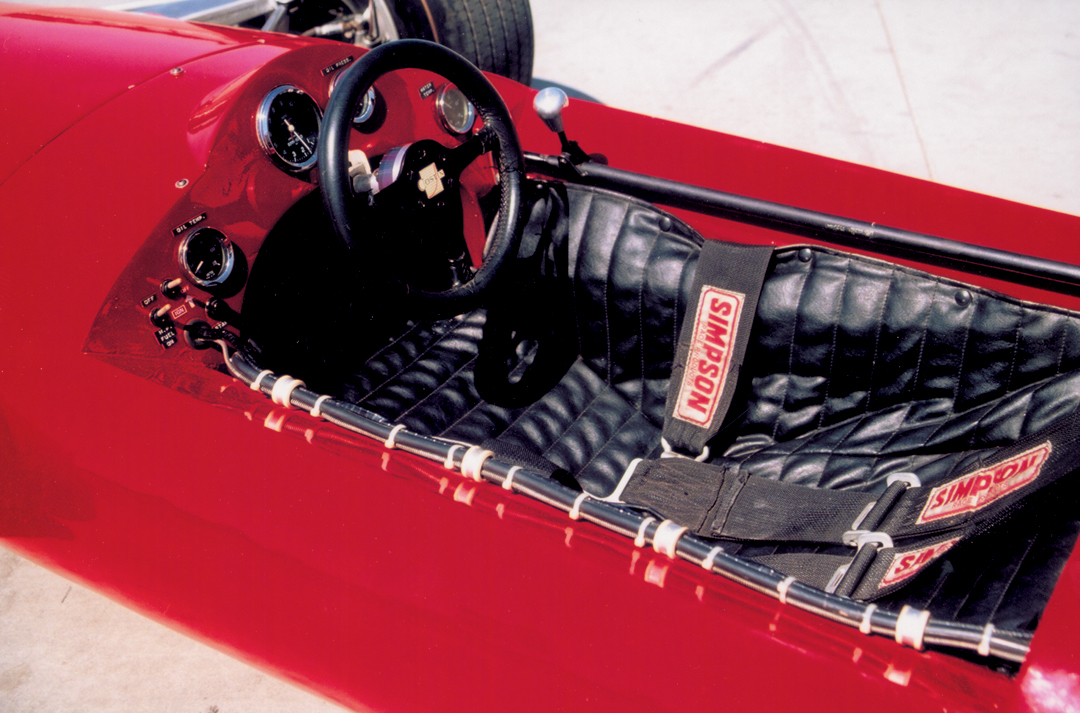

Well, it was a bit more complicated than that. Blain came in from his few laps fairly rapidly, attempting to lift himself in the seat, which was quickly filling with boiling water. A search for the problem gave us a chance to witness first hand just how challenging the Protos can be to work on, as one of the water pipes, which runs from the front through the tub, had sprung a leak. Apparently, a welded patch from its early racing days had come off, but through the valiant efforts of Blaine’s son, Brody, the problem was quickly mended. The next issue was about getting in the car. Fitting in the narrow tub required a fair bit of squeezing and shoving. Once that was accomplished, it came time to fit the canopy. Now Rodriguez was small, but he couldn’t have been this small! The cockpit surround barely fit around my shoulders, and I had to bend my legs severely to manage the pedals, with a good chance that I couldn’t fully depress the clutch. A little bit of claustrophobia didn’t help, nor did the thought of trying to shift gears with the little finger of my right hand!

Strangely, a transformation took place as soon as the Firestone (6.50/13.50-13 rear, 5.25/9.75-13 front) tires got some bite and the car was away. (These were original tires, so I should have worried about those too!) But I was able to slide a bit further down into the leather racing seat and get to grips with the next order of business, which was driving in a Coke bottle with a little slot in the end of it. It took full concentration to keep one’s eyes focusing through the slot in the canopy, as a glance either way created some interesting distortions to the apex of a corner! How was it possible to come down from 170 mph into a corner this way? While the Spax adjustable shock absorbers might have wanted renewing, the ride was immediately more stable than expected. There’s no feeling like being in a low slung single-seater, with all the wheels and suspension visible to you, and in this case the wheels were Costin’s own six stud design.

There is a minimum of gauges in this car, and that’s a good thing, since our earlier water problems necessitated my keeping a watchful eye on the temperature gauge. However, once focused on driving, the gear change was much easier than I expected – the changes being clean and quick – with getting into first being the real hard task. The gear gate is even bracketed into the wooden tub – bolted and glued!

The steering of the Protos is precise and responds to minimal movement. Having raced some FVA-engined cars, I felt this unit was particularly friendly, not suffering the “peakiness” of some FVAs, which tend to have a narrow, usable rev range. This can be a real problem in a heavier sports car, but mated to this lightweight chassis, it performs like a dream. I was able to use most of the allowable revs while getting familiar with the interesting and tough Buttonwillow circuit. The engine pulled cleanly through the wide sweeps and accelerated rapidly away onto the straights. Going into top gear at 6700 rpm, I was aware of the car almost leaping forward, a clear indication of how little wind resistance was being encountered. The air penetration was absolutely as good as it was meant to be… you are going much quicker than you expect in relation to the amount of throttle you are using. The other surprise was the serious lack of noise from chassis rattle. The wooden tub absorbs all the sound and allows the singing exhaust note to guide the driver through the gears. Even though Buttonwillow is bumpy in places and the car moves around on the road, the experience is one of total confidence and pleasure. I had even cast aside the seat belts to have a true period feel, and I was certainly getting it, flowing up and down the box, finding the brakes easy to manage and trying to shrink a bit more, so I really could be Pedro!

Buying and owning a Protos

Brian Blain is very clear what he wants to happen with his cars. He would like to see them stay together as a pair, perhaps even return to Europe. This pair will of course be unique, if and when they go on the market. Setting a price is considerably difficult, HCP-1 being worth somewhere between $60,000 to $80,000, but there might be a discount on the set. Brian is so fond of the cars, however, he might not be able to let them go.

The Protos is a virtually perfect machine for historic F2, as the history is so typical of the time, and some significant drivers have had their bottoms in these seats. Running an FVA is not an overly complex task, though pulling those water pipes out of the monocoque for a thorough look will take some patience! You will need to be a thinner, shorter sort of person even though Brian Hart wasn’t!

Specifications

Chassis: Wooden stressed skin with thin ply skins adhesive-bonded to plywood bulkheads to form body chassis unit; multi-tubular steel rear space frame with inboard front suspension carried on transverse magnesium beam.

Track: 5’

Wheel-base: 7’ 10”

Weight: 1,036 lbs

Suspension: Front: Front-lower wishbones, raked fabricated upper rocker arms and inboard coil springs/dampers. Rear: Rear-conventional lower wishbones with parallel upper transverse rods and radius arms.

Engine: Cosworth FVA, DOHC

Cylinders: 4

Capacity: 1594 cc

Valves: 16

Power: 225 bhp @ 9500 rpm

Fuel system: Lucas fuel injection

Top speed: 174 mph

Gearbox: Hewland FT200 5-speed with limited slip differential.

Brakes: Girling discs

Tires: Firestone

Wheels: Costin alloy

Resources

Costin, F.

Race of My Life

Autosport, Nov. 25,1993

Hodges, D.

A-Z of Formula Racing Cars

Bay View Books, 1990, Devon, U.K. ISBN – 1 870979 16 8

Nye, D. & R. Whittlesea

Costin’s Wooden Wonder?

Motor, Jan.14, 1984

Phillips, I.

Birthplace of a Generation

Autosport, Oct.4, 1984

Special thanks to: Brian Blain, Brody Blain and Jim Putnam for a truly great day, and to Richard Whittlesea for his help.