Talking with famed Indianapolis chassis builder

A. J. Watson, the question arises about the front, twin air inlets—the signature of the Watson Roadster. The first four Watson Roadsters, of 1956–1958, had a single air inlet and chrome grille, so why the change? Surely it had some advantage. Was it the result of wind-tunnel testing?

“Naw,” says Watson. “We went to Daytona in 1959 with Rodger Ward and he crashed. I sent the car back to California and told (fabricator) Wayne Ewing to straighten the nose. He straightened it and made a twin-holer out of it and didn’t tell me. So it was just his idea and it stuck with us and we had it ever since.”

A. J. Watson was the most successful chassis builder of the Roadster era (1953–1964). Today, at age 83, he is the sole surviving member of a small but dedicated group of American chassis builders that crafted approximately 110 Indy Roadsters. What is an Indy Roadster? It is part racecar and part hot-rod, a cross between a conventional front-engine Indy car of its day—where the driver sat exposed atop the drive line—and a lake-bed hotrod of the ’32 Ford Roadster variety where the driver sat beside the drive line partially covered by bodywork. The engine was mounted left of center, thus creating a left-side weight bias that improved cornering speed and was ideal for Indy’s four left turns.

If you had a mind to win the Indianapolis 500 in the mid-1950s, Southern California was the place to go, and A. J. Watson was among five men you would have wanted to see. They all had their shops within 15 miles of each other in the Los Angeles area, so you could meet all five in a single afternoon if short of time. There was flamboyant Frank Kurtis, who developed the very first Roadster in 1952. With four Indy wins to his credit through 1954—two of them with Roadsters—you wouldn’t have gone wrong buying a chassis from Frank Kurtis. His Glendale shop turned out cars with production-line efficiency, so delivery for the next Indy 500 was guaranteed. If you were a gambling man, then you would want to see Quin Epperly. A first-rate engineer and welder, Epperly, working in conjunction with George Salih, was planning a new unorthodox car with the engine cantilevered over to one side, thereby creating a very low center of gravity. The design made sense on paper, but would it work? There was Eddie Kuzma, metal fabricator par excellence. The upright chassis he built for J. C. Agajanian won the 1952 Indy 500. Still regarded as a dirt-track specialist, he has a Roadster in the works. If you had an eye for old-world craftsmanship, then Luji Lesovsky was your man. Lesovsky built cars with painstaking care—and almost entirely by himself—but don’t expect delivery for at least a year. Lastly, there was A. J. Watson, a former aircraft worker turned racecar builder. At age 30, he was the youngest of the group and the least experienced. He had a small shop a few blocks from Kurtis-Kraft in Glendale.

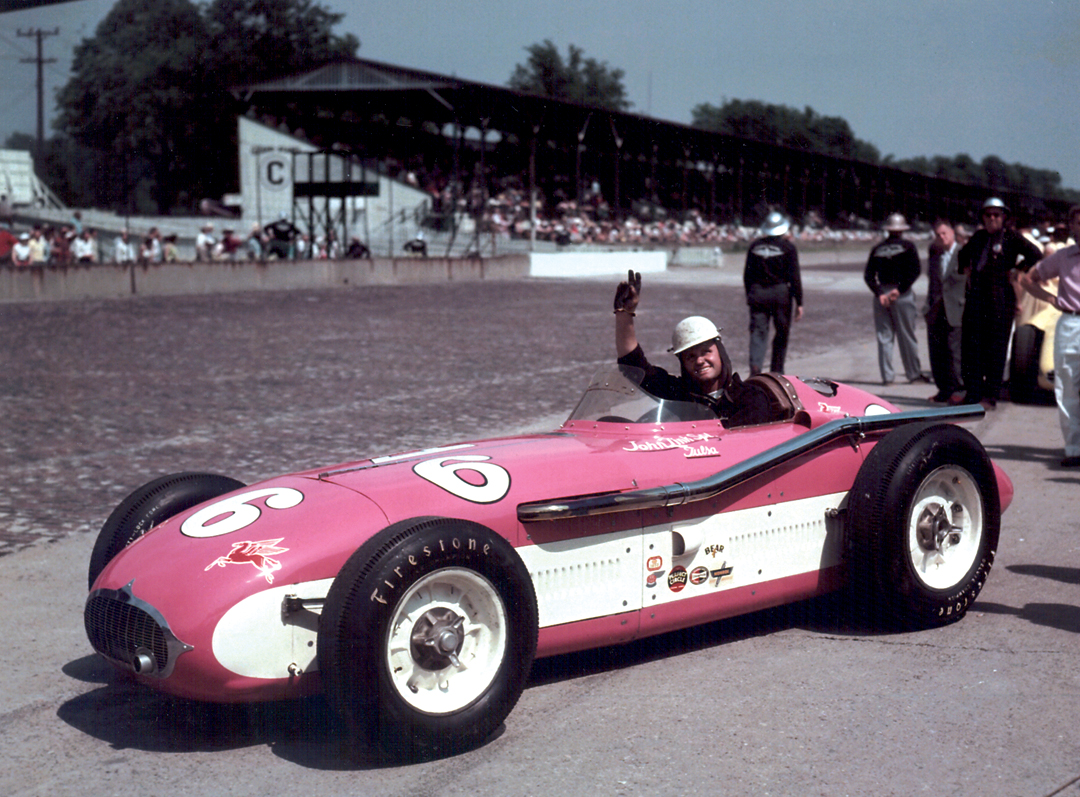

Watson was not a sheet metal fabricator like Eddie Kuzma or Luji Lesovsky, or an engineer like Quin Epperly, or an innovator like Frank Kurtis, nor was he handy at the drawing board. What Watson possessed was an eye for simplicity. He was the man John Zink went to see at the end of the 1954 season. Money was not a problem. Zink managed an industrial heating conglomerate in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “He offered to double my salary, if I went to work for him,” Watson says. “I was making $75 a week and he offered to pay me $150, which was pretty good money then.” To start, Zink bought a Kurtis 500C Roadster that Watson rebuilt from the ground up. First time out at Indy, in 1955, with veteran Bob Sweikert driving, the car won.

“The next year, in 1956, John Zink asked me to build a car for him,” says Watson. “So I took the Kurtis, and all I did was I figured out how to make it better. I made it narrower and lower and lighter.” His car featured a chassis of chrome molybdenum steel tubes in place of the heavy, channel-section frame of the Kurtis design. Some 200 pounds lighter than a Kurtis helped make it faster than a Kurtis. With Pat Flaherty driving, the Watson Roadster took pole, led 127 laps, and won that year’s 500 easily.

The next two years at the Speedway belonged to Quin Epperly. His radical lay-down engine chassis dubbed “the sidewinder” worked perfectly, and his car won the 500 both years, in 1957 (Sam Hanks driving) and 1958 (Jimmy Bryan driving). But by 1958 it was clear that Watson’s machine was the car to beat. At the Speedway that year, three Watson Roadsters started from the front row, but the fastest two—driven by Dick Rathmann and Ed Eilsian—were knocked out in a freak multi-car pile-up on the first lap of the race. A month later, at the Race of Two Worlds, in Monza, Italy, Jim Rathmann (Dick Rathmann’s brother) dominated all three-heats of the 500-mile race in a Watson Roadster.

“It was the car Elisian crashed at the Speedway,” says Watson. “He didn’t even hurt the car. We never even pulled the engine out. We straightened the nose and the header that was bent, and went right on to Monza.”

Watson was building Roadsters for other people now, which was a sore spot for team-owner John Zink. “He didn’t like it,” Watson confides. “He finally got mad. He tried to stop me by saying, ‘You’ve got to move to Tulsa or I’m going to have to let you go.’” Watson saw himself as a chassis builder and had no desire to move from Los Angeles and its many suppliers, so the two parted company.

It was at this point that Bob Wilke stepped in. Heir to the Leader Card envelope empire, Wilke had no problem with Watson building cars for other owners. “We worked on a percentage deal,” says Watson. “I just took 20 percent off the top; he got the rest and he paid the bills. He was happy, and I was happy.” With Rodger Ward signed as driver for the 1959 season, the trio of Ward, Watson and Wilke started winning immediately and soon were being called the “Flying W’s.”

The Watson Roadster was in demand. At the top of the list was Monza winner Jim Rathmann, now driving for Texan Lindsey Hopkins. Watson had time to complete only two cars for the 1959 500-mile-race—one for Ward and one for Rathmann. At Indy, the cars finished 1-2, with Ward in front. Ward went on to win the National Championship. A third car, built later that year, went to team owner J. C. Agajanian. It would later be dubbed “Old Calhoun” by Parnelli Jones and would win the 1963 Indy 500.

In some ways, 1960 was a repeat of 1959. Watson was again pressed for time and only built two cars, one for Ward and one for Rathmann, who with the backing of a couple of wealthy friends had formed his own team. “Rathmann wanted me to build him a car so bad, he paid $15,000 for it, the most I ever got for a Roadster,” says Watson. “Usually I got about $10,000 to $12,000.” Rathmann paid a premium but was more than compensated by turning the tables on Ward and winning that year’s Indy 500. Ward finished 2nd.

Unable to keep up with demand, Watson allowed others to copy his design. Wayne Ewing, the fabricator who fashioned the Watson Roadster’s trademark nose, built a copy for crew chief Clint Brawner (for Eddie Sachs) while a Texas fabricator named Floyd Trevis built a copy for crew chief George Bignotti (for A. J. Foyt). As fate would have it, these cars finished 1-2 at the Speedway that year, with Foyt 1st, Sachs 2nd. Ward finished 3rd. But times were changing. Englishman John Cooper entered a rear-engine car in that year’s 500. Vastly underpowered, it nonetheless had superior cornering speed and in the hands of two-time world champion Jack Brabham finished 9th, despite long delays in the pits.

However, Watson’s best year was yet to come, in 1962. His Leader Card team entered two cars in that year’s 500, and they finished 1-2. For Ward, it meant winning his second Indy 500 and a second National Championship. Still, Watson sensed the Roadsters’ days were numbered, and he began thinking about building a rear-engine car. But with demand for his Roadster greater than ever, nothing came of it. Over the winter of 1962–1963, his tiny Glendale shop filled orders for eight new Roadsters, the most ever.

If there is a date when the reign of the Roadster ended, it is probably March 27, 1963. That day, at a test session at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, a rear-engine Lotus-Ford driven by Dan Gurney lapped the famed oval at 150.504 miles-per-hour. Only one car had ever gone faster, a Roadster with 75 more horsepower, driven by Parnelli Jones. Jones won the 1963 Indy race by driving all 500 miles absolutely flat-out and by extending his lead during several yellow caution lights, which was against the rules, but race officials did not uphold the rules that day. Future World Champion and Indy rookie Jimmy Clark, cruising most of the way, finished 2nd in a Lotus Ford. Foyt and Ward finished a lap behind Clark, in 3rd and 4th place, respectively.

A rear-engine car had failed to win, but the Roadsters were beaten. Watson said afterwards, “I’m sort of sad. It’s awful tough when you’ve worked like hell to get to the top to have to start all over again with something new, something none of us knows much about.”

The following May, a Watson Roadster (driven by Foyt) won the 500 for the last time after all three Lotus-Fords dropped out. No one, not even the few remaining die-hard Roadster owners, celebrated that day as two drivers were killed in a flaming second-lap accident. Watson was among the old-guard who already had made the switch: he built two rear-engine cars that year, one for Ward who finished 2nd and one for Don Branson who finished 12th.

A lot of people took potshots at the Roadster builders for persisting so long with an obsolete design while the rest of the racing world was switching to rear-engine cars. “Dinosaurs” they called the Roadsters. Colin Chapman of Lotus was particularly critical saying the typical Roadster was in fact little changed from the Depression-era cars that competed at the Speedway in the 1930s. Perhaps, but it’s worth noting that a mere ten years before—in 1953—the average Indy car had magnesium wheels, tubular shocks, disc brakes, fuel injection, and fiberglass bodies while their European counterparts still relied on wire wheels, lever-action shocks, drum brakes, carburetors, and aluminum bodies. As late as 1958, when the Roadsters faced front-engine Ferraris, Maseratis and Jaguars on Monza’s banked oval, the Roadsters still held a distinct technological edge. True, the European cars had fully independent suspension, but given the state of chassis tuning in those days, it’s likely a good Roadster with fully symmetrical suspension would have held its own against such competition on most European road circuits and likely prevailed on smooth-surfaced tracks such as Reims and Silverstone.

It was development of the rear-engine Formula One of John Cooper in 1958 and 1959 that had pushed European car builders ahead on the technological curve. Chapman’s development of the fully-integrated monocoque chassis in 1962 pushed them still further ahead. True, the Americans had been caught napping, but not for 30 years as Chapman would have had you believe. Chapman, it will be remembered, was innovative for the sake of being innovative. The Roadster builders took the position, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

With a bevy of suppliers manufacturing engines, drive trains and other various racing components, the Roadsters were in fact kit cars, not unlike the kit cars that dominated F1 in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. A few myths have persisted down through the years about how Roadster chassis were actually designed and built. Is it true that Watson never designed his cars in the conventional manner on the drawing board, but with chalk marks on the shop floor?

“Well, it kind of is,” Watson admits. “I had marks on the floor to lay out the frame and stuff. Later on, I used a piece of plywood that was more complicated and put it up on a sawhorse, so I didn’t have to bend over. I never made a jig. I just never got around to it. Later on, when I was building four or six or eight cars, I made a cardboard template for all the pieces. I would send them downtown to some frame-cutters to cut the pieces. We’d get them back, clamp the frame together, put the cross members in, and then we’d just arc everything together.”

The engine of choice was the 4-cylinder Offenhauser. In an era when Roadster builders were tilting the venerable Offy engine this way and that in a ceaseless search for the ideal weight distribution, Watson mounted his Offy upright, 12 inches left of center, and never varied. The Offy was mated to a Dale Drake-designed gearbox that in turn delivered torque to the driving wheels through a Halibrand quick-change rear axle. The Offy transmission in fact dated back to the 1930s, so Chapman was partially correct. Says Watson: “From the outside you can’t tell an Offy trans from a Model A trans, except that it’s made of aluminum and has stronger components inside. It has four gears, but only two were used.” Watson ran beam axles front and rear, offset 1.5 inches, transverse torsion-bars with trailing links in front and leading links in rear, International truck spindles, Halibrand steering, Halibrand disc brakes, and Halibrand mag wheels (16 inch front, 18 inch rear). Total weight was about 1,550 pounds dry. In 1963, the final production year, he switched from torsion-bars to coil-springs for a weight savings of 100 pounds. Between 1956 and 1963, he built 23 Roadsters in all.

Watson eschewed adornment. He did away with chrome grilles, front nerf bars, chrome lettering and anything else that wasn’t absolutely necessary. Above all, he believed in simplicity and, like his contemporary John Cooper, lived by the adage, “If it looks right, it is right.” The Watson Roadsters were faster mainly because they were lighter. As racecars go, they were uncomplicated and therefore easy to service and set up. As important, Watson raced what he sold.

In the final analysis, Watson was more chief mechanic than racecar builder and, in this sense, was not unlike George Bignotti and Clint Brawner, gifted mechanics who could take someone else’s car and make it faster. However, while Bignotti and Brawner switched to rear-engine cars and continued winning, Watson struggled.

“I didn’t listen to anything by anybody back then,” he explains. “I thought I was the smartest, so if I had listened more…” his voice trails off. He continues, “My ’65 (rear-engine) car didn’t work at all. Danny Jones was working for Ford at the time and he came down to me and said, you need to put this rod on the left side and this one on the right, and he was right, but I didn’t do it, and we missed the show (Ward failed to qualify; he quit the team soon after). Later on, why we did that and the car won at Atlanta, with Johnny Rutherford.” Ironically, the 1965 car was the most wholly original car Watson ever built. While everyone else was making Lotus and Brabham copies, Watson produced a wedged-shaped car three years ahead of everyone else. Had Watson pursued the concept, his success might have continued. As it was, the 1965 car won, but only once.

In 1966, Watson began buying other people’s cars. Through the end of the 1960s and throughout most of the 1970s, he ran Eagles but with nothing like the success he enjoyed in the Roadster era. By the mid-1980s, after failing to qualify two years in a row at Indy, he retired. “I was there but I wasn’t,” he says. For the past ten years he has been building Roadsters again, “for ten times what I was getting in the 1960s.” Each one takes about a year to build and there is always a buyer waiting.

Watson’s legacy will be forever linked with the Roadster. Frank Kurtis may have built more of them—estimates are he made at least 50—but Watson won more races. During the Roadster’s 11-year reign at the Speedway, Watson Roadsters entered Victory Lane six times (seven if you count Floyd Trevis’s Watson copy). Kurtis-Kraft Roadsters captured three 500s (one with Watson as crew chief). The Epperly Roadster won two 500s.

What became of the other Roadster builders? Luji Lesovsky built several variations with limited success. His best year was 1959 when Johnny Thomson put one of his cars on the pole and in the race finished 3rd. In 1962, Lesovsky decided A. J. Watson had a better idea and built a Watson copy of his own. He went to work for A. J. Foyt and did the sheet aluminum fabrication on Foyt’s 1967 Indy-winning Coyote. As mentioned above, a Kuzma dirt car won at the Brickyard in 1952. Kuzma’s best year as a Roadster builder was 1957 when Jimmy Bryan drove his car to 3rd place at Indy and a month later to 1st place in the Race of Two Worlds. Kuzma did sheet metal fabrication on Lotuses for both Jones and Foyt. In 1970, he replaced Lesovsky at Foyt’s Houston shop when the latter was lured away by Roger Penske. Quin Epperly never equaled his Speedway success of 1957–1958 although some, including Jones, believed his 1960–1961 cars were quicker than Watson’s, but the record does not bear this out. In 1965, he set out to build a rear-engine car similar to his “sidewinder” Roadster—with a side-mounted Offy. The car was never completed. He turned to welding full time, in which he was without peer. His specialty: welding cracked, aluminum, cylinder heads and engine blocks with seamless precision. Frank Kurtis, his five Indy wins notwithstanding (two with dirt cars, three with Roadsters), enjoyed even greater success with midgets (building 1,000). The National Midget Auto Racing Hall of Fame described the Kurtis-Kraft midget as “virtually unbeatable for over 20 years.”

Forty years on the Roadsters are perhaps the most popular cars in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, where a disproportionately large number—eight winning cars—are on permanent display. They are: the 1953–54 Kurtis 500A driven by Billy Vuckovich; the 1955 Kurtis 500C driven by Bob Sweikert; the 1957–58 Salih-Epperly driven by Sam Hanks (’57) and Jimmy Bryan (’58); the 1960 Watson driven by Jim Rathmann; the 1961 Trevis driven by A. J. Foyt; the 1962 Watson driven by Rodger Ward; the 1963 Watson driven by Parnelli Jones, and the 1964 Watson driven by Foyt The 1956 Watson driven by Pat Flaherty remains in possession of the Zink Family; the 1959 Watson driven by Ward is privately owned. All the Museum Roadsters are expected to be displayed this summer at the Monterey Historics.