Photo: Pete Austin

One of the problems in writing this profile is the temptation to indulge in a long list of Chris Amon misfortunes—and there were plenty of them. Chris, however, has always been a really nice guy, and inevitably ends up looking like he perhaps didn’t know what he was doing in choosing teams, leaving teams, and setting up his own projects. A summary of his career always tends to strengthen that stereotype. One of his misfortunes was to have his biography written by someone who failed to ask the penetrating questions; i.e., why did he do the things he did. Always choose your biographer carefully.

Briefly, however, here are some of the key points about the man who should have been a champion, but never won a Grand Prix.

Born in Bulls in New Zealand in 1943, he started competition in the 1950s with a self-fettled Austin A40 Special, and progressed via a 1.5-liter Cooper, an old 250F Maserati and then began to make his name with an ex-Bruce McLaren Cooper T51. Reg Parnell convinced Chris to head for the UK. He was a member of Parnell’s team in 1963 and put in a full F1 season in the Climax-powered Lola, usually qualifying faster than his more experienced teammates. It was a mechanically disastrous season, but he salvaged a 7th at both the British and French GPs. At the time he was sharing a well-known London apartment with fellow drivers Mike Hailwood, Tony Maggs and Peter Revson.

Photo: Pete Austin

Over the next few years he left and then rejoined the Parnell team, had a stint in McLaren Can-Am cars, drove a Brabham and then a Cooper. In 1966 Chris and McLaren won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in a Ford MkII, and Enzo Ferrari invited him into his team for 1967, which was a terrible year for Ferrari, as he lost Bandini at Monaco and then Mike Parkes broke his legs at Spa, leaving Amon as the sole team driver for much of the season. His three 3rd places brought him fourth in the championship, and in sports cars he won the Daytona and Monza races, and was 2nd with Jackie Stewart at Brands Hatch. The 1968 season should have been his year in F1. He qualified on pole three times, led several races and yet never won. I was present at the British Grand Prix to witness one of his greatest drives, pressing Siffert to the very end. He continued his winning ways in 1969 in the Tasman series, but had no luck at all in GPs, so he left Ferrari for March in 1970, the year when Ferrari’s reliability returned.

March was supposed to provide Amon with a small, professional team, but they then decided to build cars for everyone. He won the non-championship International Trophy, always qualified and ran well, and almost won only to break down near the end of a race. He moved to Matra for 1971. Again he won an early season non-championship race, this time in Argentina, and then it was yet another year of good qualifying, a few decent results and many retirements. Same for 1972, when he had more heartbreaking “almost” wins. At the end of the year he set up an F2 engine building company with Aubrey Woods, but it did not last very long. For 1973, he headed to Tecno, which had started in F1 the previous year. On the basis of their success in F3 and F2, it was reasonable to think the flat-12 Tecno might do quite well, but again it didn’t turn out that way. Part way through the season Amon got Gordon Fowell to build a new chassis, which again had a feel of promise in it, but it just wouldn’t work and Amon again packed up and left at the end of the season. He had a few drives for Tyrrell, and was in a third car at Watkins Glen with Stewart and Cevert. As bad luck would have it, Cevert was killed in practice and the other two cars were withdrawn.

Photo: Pete Austin

Enter the Amon AF101

At the end of 1973, Amon was feeling he was going nowhere, although he still had enormous enthusiasm for racing and felt he could probably do just as well on his own as he had in the various teams he had been part of. There was no doubt that the greater part of his misfortunes had very little to do with him. He still had some funds available, and in spite of the failure of the previous engine business, he decided to revive Chris Amon Racing and attempt to build his own small team where he, hopefully, could focus his attention on driving and getting his own car right. He very much wanted to keep the whole thing simple and uncomplicated, and in that perhaps he might be seen as being naive, given the rate at which F1 technology was beginning to develop.

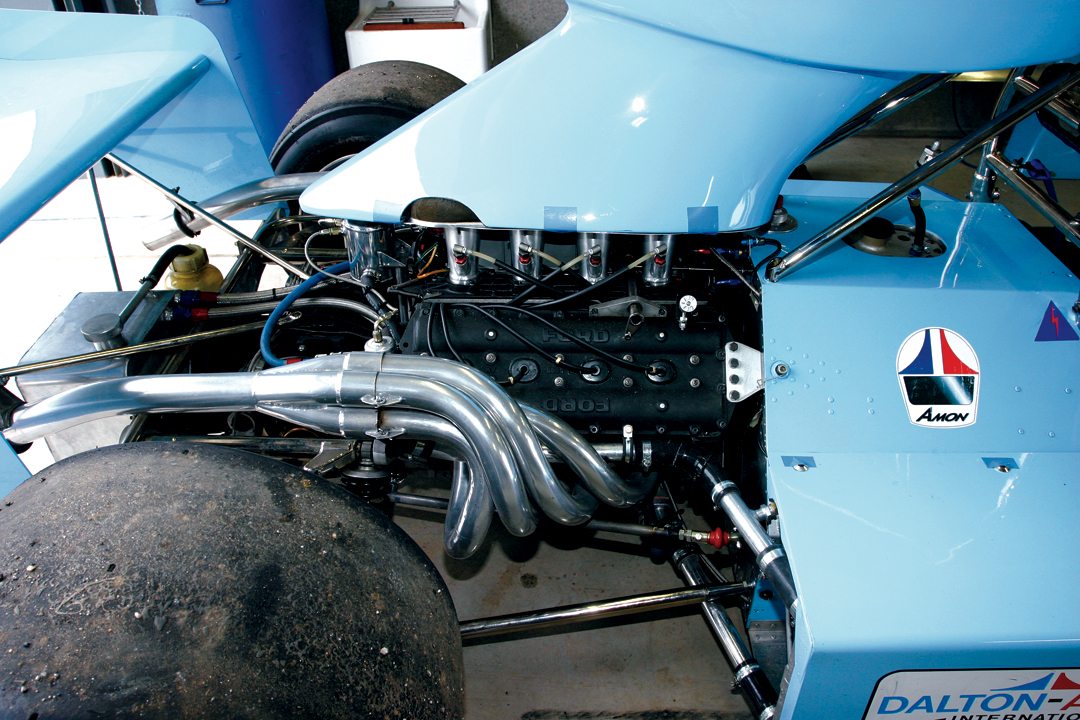

Amon managed to secure backing from John Dalton; not a huge amount, but sufficient to take on Gordon Fowell once again to design a sophisticated new chassis. Though Fowell’s experience was somewhat limited, he had Amon’s respect, and was given a fairly free hand to come up with new ideas. John Thompson, who had manufactured cars in F1 for Ferrari, Surtees and Tecno, would be responsible for the building of the car in Northamptonshire. Professor Tom Boyce would look after the aerodynamic and bodywork package, and other capable people in the team were ex-McLaren and Rondel racing mechanic Richie Bray, with Ray Buckley responsible for the car’s Cosworth DFV. Amon’s friend, Australian journalist David McKay, also brought Larry Perkins into the small team with his own F3 mechanic, Charlie Coburn. Perkins was an able driver as well as engineer, very adaptable, and willing to work for Amon for a very low rate of pay as mechanic and test driver.

Photo: Pete Austin

Amon was clear about what he wanted from the project:

“It was a high-tech venture, but we did it in the backyard. Had we built something basic, we would probably have done a lot better, but I was always striving for some kind of Utopia, because I thought I knew technically what I wanted. It was very advanced—fuel tanks in the middle, with the driver located forward a bit, titanium torsion bars. I prided myself on my ability to develop a car, but it was so difficult with this one because it just kept falling apart.”

It was not long before the “simple” in the team started to wander. There was soon talk of building an F5000 car for Larry Perkins to drive in Europe and North America with a view to possibly selling some cars to the USA. The early team plans were solid and cautious, with a clear vision of how Amon and Perkins would work together to test and develop the car, with Perkins being a likely team driver further down the road.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

The Fowell innovations looked interesting and sound. The fuel tank was to be a single unit placed between the driver and the engine, the first F1 car to do this. This was a real move away from the tradition of multiple tanks, and in addition to improving weight balance, was clearly much safer than having the driver surrounded by fuel tanks. As a result the center of gravity was lower, also improving overall balance. The car employed titanium torsion bars in the suspension instead of coil springs, and also had inboard brakes.

Amon had been in the center of wing development in the 1967 to 1969 period, especially at Ferrari, and had seen the best and worst of what wing technology could do. He retained his interest in aerodynamics, and Boyce evolved a package that would try to make the best of their combined knowledge. A great deal of testing was done on a number of components, including the airflow inside the large airbox, and on the size and shape of nosecone, or should I say nosecones, because in the end there were lots of them. Work went into making the nose and front wing work together, and you can’t really fault the team over the lengths they went to get it right. Tony Southgate would later say that the AF101 was a real marker for the future, a milestone in the development of cars with central fuel tanks and “low polar momnet” characteristics. Southgate thought that if the Amon car had sidepods and skirts it would look at home among the later ground-effect cars.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

Nevertheless, with all the optimism, there was reality. By the time the funding was in place, the construction was already behind schedule for the 1974 season, and the team missed the opening Brazilian Grand Prix, as well as the non-championship Race of Champions at Brands Hatch. There were many very frustrating test sessions at Goodwood and Silverstone. Amon recalls that at “that first test at Goodwood a wheel fell off, and then it happened again at Silverstone. I only had to get in and something would fall off.”

It was apparent at Goodwood that there were structural weaknesses in the design. Amon had the right front wheel shear off at 140 mph under braking at Madgewick because the CV joints in the hubs were moving. He was fortunate to escape the episode unscathed and the chassis was undamaged, but it made Amon very nervous and started a policy of strengthening everything, which then made the car quite heavy. Despite all the testing, there were just too many problems to sort out, so the decision was made to enter the International Trophy meeting at Silverstone.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

Struggle to the grid

There was an interesting grid lineup as the Lotus 76 was there for Ronnie Peterson, and that bristled with new Chapman technology, and there was a Lyncar and a new Ensign for Brian Redman. Amon went out in Friday practice and set a “leisurely” time some eight seconds slower than James Hunt’s eventual pole time in the Hesketh 308. Amon came in to report brake vibration and was concerned that the Goodwood problem was still there. With the death of his former flatmate Peter Revson still fresh in his mind, Amon and John Dalton decided to do further work on the car and it didn’t appear again over the weekend. Hunt won the race from Jochen Mass in the Surtees TS16 from a field that included F5000 as well as F1 cars. It had not been an auspicious debut for the Amon team.

Having missed the first three Grands Prix, several weeks of hard effort went into the car before it headed off for the next event, the Spanish GP at Jarama on April 28. Further testing had brought the disappearance of Boyce’s reverse-curve nose in favor of a more conventional front end treatment. The brake vibration again appeared in practice, but Amon got in a much more reasonable time some three seconds off Clay Regazzoni’s Ferrari pole time. He managed to be quicker than Rikki von Opel in the works Brabham BT44, Schenken in the Trojan and the two non-qualifying cars of Tom Belso and Guy Edwards. With the brakes still a considerable worry, and the circuit now wet with rain, the team decided to use the race as a test session and try to do some further sorting. Chris ran well in about 21st spot until lap 23 when a brake shaft snapped. He managed not to hit anything, but it was now clear that the whole suspension and brake setup needed re-thinking. Thus was the Belgian race given a miss in hopes that things could be improved for Monaco. Lauda won in Spain and was beaten into 2nd place by Fittipaldi’s McLaren M23 at Nivelles in Belgium.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

Yet another new nose configuration appeared on the AF101 when it rolled out at Monaco. This time the radiator was located in the wide, high-downforce nose. A major change had taken place in the braking department and the team had reverted to outboard brakes in hopes of solving the never-ending vibration troubles. This was to be a very tense weekend as it was clear from the start that only 25 of the 28 cars entered would qualify. While Lauda was taking pole from teammate Regazzoni in the Ferrari 312B3 and Ronnie Peterson, back in a Lotus 72E for this race, the real struggling was at the other end of the grid. Amon was having a real battle with Ickx in the second Lotus 72E, Carlos Pace in the Surtees and Graham Hill in the Lola T370. The Amon was handling very well on the tight Monaco circuit, a terrible place to have to be taking big risks just to qualify. In the end, Amon managed 20th place behind Ickx, ahead of Hill, Migault in the BRM, John Watson in the Brabham and Schenken in the Trojan.

In spite of the tremendous efforts to qualify, it was clear that the front hubs were still not working properly. A crash at Monaco would not only be painful, but financially crippling, and the very difficult decision was made not to start as Amon felt the hubs would fail again. The financial situation now forced the team to re-think, again, and forced the team to miss the Swedish, Dutch, French and British races. Scheckter, Peterson and Lauda were winning races, though Fittipaldi was still in contention for the championship. Nine weeks after Monaco, the sky-blue Amon AF101 reappeared at the Nürburgring for the German Grand Prix.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

A great deal of work on several fronts had been carried out, and at the Ring yet another new front wing arrangement was in place, but there was yet more pain to come. Chris was unwell during the weekend and managed just one timed lap, during which the airbox fell off! The time was 90 seconds off the pace and on Saturday Amon was still so ill that Larry Perkins was put in the car to attempt to qualify. At the beginning of the project, Larry had expected to get lots of seat time to prepare him to become a Grand Prix driver, but in fact he’d hardly been in the car at all. Thus, at the daunting Nürburgring he had an impossible task. He ended up spinning into the Armco, 15 seconds slower than anyone else and 45 seconds off the pace, so couldn’t qualify. It was a bad weekend for the “down under” crowd altogether. Howden Ganley had injured himself crashing the awful Maki, Schenken couldn’t qualify the Trojan, Denny Hulme crashed his McLaren and Vern Schuppan had the gearbox break on the Ensign. None of this made Amon and Perkins feel any better, however.

After skipping the Austrian race, it was a last-ditch attempt to redeem something at Monza in September. In spite of everything else that needed doing, yet one more new nose appeared for the Italian race. Maybe that was one of the problems—somehow failing to tackle the car’s Achilles Heel was symptomatic of why things never got better. By now the money was gone. Amon managed only 30th best time at Monza in qualifying with the car handling badly. Six cars failed to qualify and Amon was by far the best of those six drivers, but his car was only quicker than the Surtees of Leo Kinnunen. Chris subsequently decided to shut down the operation and the car never ran in anger again—until it appeared for our test.

Whence the AF101

After the team returned from Monza, the car was relegated to a shed in Woldingham where it sat and rusted for some ten years. It was found with some parts missing by one Andrew Smith, who did some restoration on it, and later in the 1980s it found its way to the collection of Erwin Derichs where it also sat untouched for many years. Then in 2005, Ron Maydon, who runs the Grand Prix Masters race series and competes regularly himself, visited Derich’s workshops to look at a March:

“I saw the Eifeland car and saw the Amon in the background and asked what that was and he said it was an F1 car no one wants, and I thought that might be cheap, so it went from there. I had to sort out what configuration I wanted it in because it had been changed around so often. We rebuilt it using modern and heavier metal—the suspension bits were feather-weight. So it’s now gone from 535 kilos to 610 because we over-engineered. We couldn’t believe how small the wheel bearings were they had used, so we put much bigger ones in and in eight years have not had one of the failures that Amon had. The basic design was OK, and they were on the verge of having a really good car. I asked Chris why they didn’t make a stronger suspension, and he told me that when they were in Spain, they had a total of 110 pounds to get back to England—no money! I got a 4th at Monaco in the Historics with it, and with a really good driver it would be very quick. I took it out to New Zealand this year and Chris came to see it. On a quiet day, he came back and did a dozen laps in it and found it very quick. That was a special occasion, and he was impressed with it.”

Driving the AF101

When it came time for our test at Donington, the car had been fully restored and Ron had found a replacement Cosworth DFV and Hewland gearbox. The car was in roughly its Jarama configuration as far as front and rear wings, airbox and radiator location were concerned. Gone were all the fancy and essentially unsuccessful fancy front nose styles. The car was attractive and straightforward looking—until you got into it.

The car, as we have said, was designed to have a very low center of gravity. It is indeed very low, and the driver does not have the usual fully enveloping structure and bodywork to make him feel safe inside. I found myself sitting up in the air. With the car’s less than perfect pedigree I was pretty wary about what might be in store. The cockpit, aside from being small, was pretty sparse and there were minimal gauges, just the basics. The surprise came, however, as soon as it pulled smoothly out of the Donington pit lane and headed out onto the enjoyable and swooping circuit. It took a few laps to get used to the forward driving position and the fact that the side bodywork didn’t come up as high as one’s armpit!

Mind you, the visibility was great, and the positioning provided a feel for everything that the car did. The DFV, as expected, pulled beautifully and combined with the Hewland ’box made for a great package. I couldn’t quite believe that I wasn’t being blown about. The aerodynamics of this configuration work well, certainly as far as the driver is concerned. There was no great rush of wind knocking me about, as the air flowed neatly up and over me into the huge airbox. With improvements made to the suspension and some chassis stiffening, the car already feels better than it must have when Amon first drove it. It’s steady and progressive into the fast right-hander at Redgate and then fabulous into the next downhill right, all the way to the Old Hairpin where second gear was a bit low and third just a bit high, but the torque was terrific and launched it into the second half of the circuit. With the new wheel bearings and the brake system having been totally revised with stronger components, there is no hint of the vibration that plagued the car in the past. In fact, it quickly inspired confidence, something that poor Chris Amon was cheated out of.

After 12 laps, the right-hand radiator sprang a leak—shades of the past—but that was quickly mended. It was a rewarding experience to see such a car come back to life. Since my test, there have been more improvements and the car has done a lot of historic racing. It’s also nice to know that Chris’ initial belief in the car was in fact justified, and that he finally got to see what its potential was.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis/Body: Lightweight narrow aluminum monocoque

Suspension: Torsion bar suspension

Engine: 3-liter Cosworth DFV V8, 450 bhp

Brakes: Both inboard and outboard used, currently inboard rear and outboard front

Weight: 610 kilograms, 1342 pounds

Tires: Firestone in period, now Avon slicks; front 10.0/20.0-13, rear 18.0/26.0-13

Acknowledgements / Resources

Many thanks to Ron Maydon for his generosity and help.

Hodges, D. A–Z of Formula Racing Cars Bay View Books, Devon UK 1998