Making its debut in 1963, the Rover P6 was introduced as the new jewel in the crown of the Rover fleet. The car was voted European Car of the Year in 1964 and it revelled in the glow of Britain’s last true motor manufacturing era. By the time the P6 reached the end of its shelf life in 1977, Britain’s motor car industry was in a spiral of decline from which it would never recover.

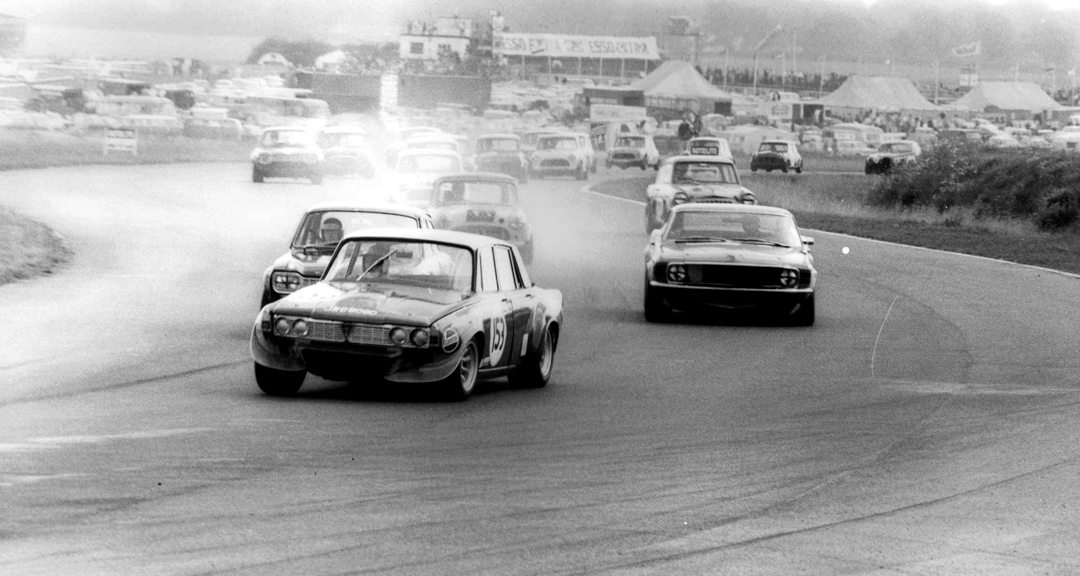

Photo: Pete Austin

The Rover P6 in its road-going 2-liter, 2.2-liter or mighty 3.5-liter specification was popular. Built at Solihull in the British West Midlands, the Rover was very much the executive’s car of the era. Used by company managers and by the police as a “Panda” car, the Rover was a car of style and only a Jaguar parked on your driveway allowed the man of middle England to feel he enjoyed a higher social standing.

The Rover’s success led to the inevitable introduction of a big-engined variant, and in April 1968 the 3500-cc Rover P6 was introduced—one year after the company had been purchased by Leyland, already owners of Triumph. The Rover V8, based on the aluminum Buick 3528-cc V8, was installed in production models and became an instant hit. The throaty engine provided Rover with a powerful unit that was ideal for the road and, more importantly, on the track.

The Leyland era of British motor manufacturing is now regarded as something of a joke. Mighty marques were assembled under one roof, each eventually losing its own identity and being swallowed up as brand partners. Rover’s position, for a while, kept the company name at the top of the pile, and those within British Leyland had a dream of sporting success. It was from those dreams that our profile car appeared.

KEEPING THE WHEELS TURNING

“You can stay in business so long as you keep on winning events that will give us worthwhile publicity. And don’t spend too much money,” were Lord Stokes’ words to Peter Browning, the BMC Competitions Manager, at the end of 1967, as another period of uncertainty surrounded the BMC Competitions Department. The range of vehicles open to the department did not fill Browning, and those involved, with confidence, and options for success in competition appeared very limited indeed.

In the last full season of rallying with the Mini, 1968, the Competitions Department had enjoyed a luckless year. The little Austin A-Series engine had been pushed to its breaking point, introducing a frightening level of unreliability as the cars from the opposition became ever more powerful. A concerted effort on the London to Sydney Marathon also took much resources, with the Austin 1800-mounted team scoring a disappointing 2nd overall when victory was really the only desired result.

Due to the economics of the time, the rallying project with the Mini was effectively placed on the sidelines and the attention switched to racing Minis in the British Saloon Car Championship. In 1969, the band of brothers from Abingdon took to the tracks and despite the now famed antics of John Rhodes and John Handley, the little cars failed to gain much success against the might of the Ford Escorts prepared and raced by the famous Broadspeed team.

Mini did continue a limited rally program with Paddy Hopkirk, scoring 2nd-place finishes on the Circuit of Ireland and Scottish Rally, as Brian Culcheth won in Scotland with his Triumph 2.5 PI Triumph. The final push of 1969 for the Leyland Group was again centered on the development of Triumph and Austin Maxi cars for the London to Mexico Marathon, which netted another 2nd-place finish in an event where victory was so urgently required to allow the continuance of participation.

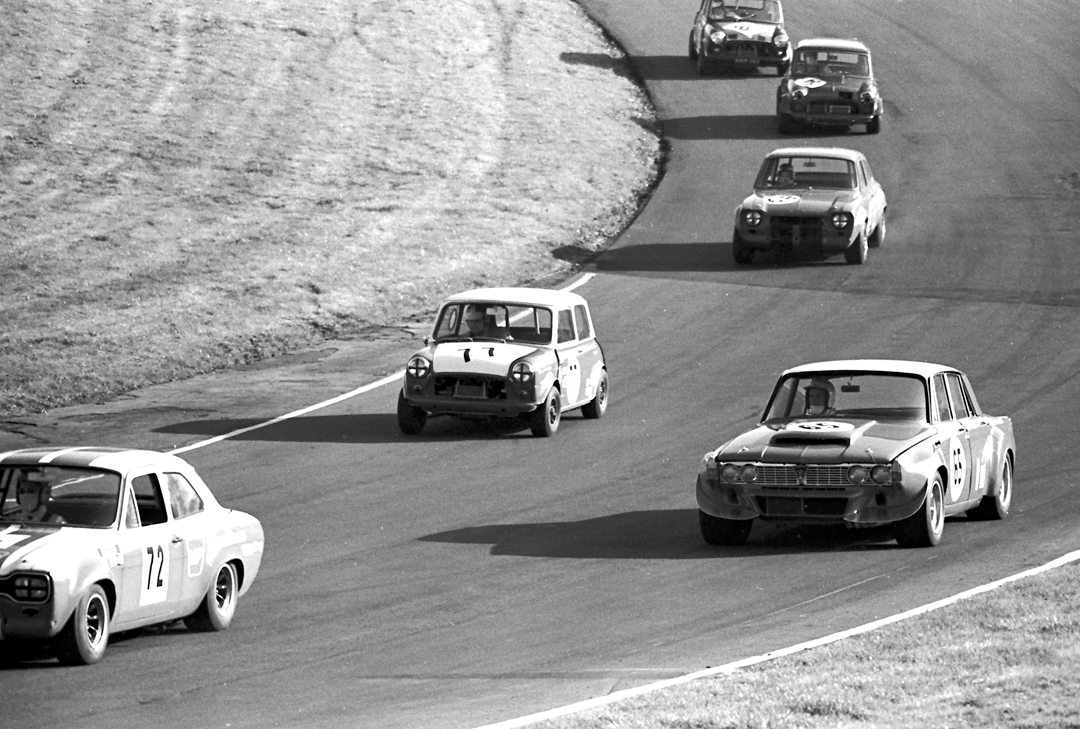

Photo: Pete Austin

Sitting at Longbridge, Lord Stokes made it very clear to the Competitions Department that he was far from happy with the results scored during the year. Instant wins and a long-term plan of attack was called for, and the introduction of some new models were heralded as the cars that could deliver success. However, the examples already in prototype phase, the Allegro and Marina vehicles, neither could, nor would, bring anything to the competition party. At Triumph, the marque was working on the new Dolomite, although a racing “Sprint” version was not anywhere near the production line, leaving competition possible for the brand—but not for short term and instant success.

MG was working on V8 designs for the MGB, but the final designs of this car were not yet scheduled for production, and the need for a turn-key car was now more important than ever before. Peter Browning recalls, “There is no substitute for sheer horsepower, and so we decided to investigate the potential of the newly announced V8 version of the Rover 2000. We knew that with Traco or Repco versions of the engine we could easily double the power output and, although the car had a Rover reputation of being a ‘gentlemen’s carriage’ one could obviously reduce the weight enormously and hopefully improve the handling.”

A four-stage program of attack was formed. It was decided that a new standard car would be prepared to compete in one of the popular televised Rallycross events at Lydden Hill in Kent, where in the past, the Mini had proven successful. If the car was a winner, or at least showed strongly, instant relief to the “we need success” vibes coming from the Longbridge works could be appeased. The second stage conceived was to build a “Club Racer” that would show the car’s on-track potential, stage three was to work the project toward the Special Stages and introduce a rallying pedigree to proceedings, and the fourth was to persuade Leyland to back the project! This backing would hopefully lead to a limited run of vehicles to obtain Group 2 homologation.

Success into the 1970s was firmly pinned on the back of the V8-powered Rover, and now the race was on!

SELLING THE IDEA

Peter Browning travelled from Abingdon to Solihull to present the Competitions Department report to the Directors at Rover. It was not an easy sell. The Rover Directors did not instantly see the appeal of why the brand should enter the competition arena. Of all the cars in the Leyland range this was one example that did not seem to require brand management. The Rover P6 had proven a popular range car and the executives in Solihull failed at first blush to see the benefit that a full competition car would bring. Browning’s proposal of a limited production run of special-equipment V8s fell on deaf ears. Only Ralph Nash, the company’s former Rally Manager, seemed interested and excited in Browning’s approach, and although he had been away from the sport for a while, he was suitably pleased that something was planned for Rover, so he arranged the presentation of an aging press fleet car for use as a base model for competition conversion. Browning was now the proud owner of “JXC 808D,” and as he left Solihull for Abingdon the race was underway!

Photo: Peter Collins

Little work was carried out on the car before it was taken to Lydden Hill for a Rallycross meeting where it was driven by Geoff Mabbs. The popular driver placed a bowler hat, curled handle umbrella and a copy of the Financial Times on its rear parcel shelf. Mabbs drove the car well, and with the legendary British motor sport commentator Murray Walker doing his finest on the BBC, the Rover gained great exposure. On the first working day of the week, a director from Rover telephoned Browning to offer up a few words of encouragement, and before Geoff Mabbs could eye his vehicle for further Rallycross outings, the team’s second phase of planning for the Rover P6 commenced.

Browning realized that time was of the essence and if JXC 808D was to meet its time targets, then a build away from the “works” was probably the safest and, in truth, only option. Competition builds within factories have always been beset by politics and delays, and in the case of our car things had to move quickly. It was decided to have the car prepared elsewhere and, as Browning adds, “Departments often, in fact, find this an arrangement of great convenience. If the project turns out to be a success you can claim all the glory and immediately take the operation back under your own wing. If it’s a failure you can tell the Board that, of course, it was nothing to do with you and pretend that it never happened! It is a policy that every Competitions Department has adopted to its advantage.”

The Rover P6 project was handed over to the partnership of Roy Pierpoint and Bill Shaw. Pierpoint was a former British Saloon Car Champion, who had much experience of running large V8-powered machines, and Bill Shaw was a well-respected builder of racing saloons. JXC 808D moved to Pierpoint’s garage in Walton-on-Thames, where its track preparation was started by two former Alan Mann Racing mechanics, Jim Morgan and Jim Rose.

The car was stripped and on the standard chassis a new lightweight racing body with extended fenders and wheel arches was fitted. The weight was reduced considerably, to around 950-kg (2090-lbs), and the front suspension modified with fabricated lower wishbones. PFTE bushings were used throughout, and ventilated disc brakes were added both front and rear to aid its stopping potential. Ten-inch wide Minilite wheel rims were fitted along with Dunlop tires.

Pierpoint looked at all the power plants available and opted for a 4.3-liter, Traco Oldsmobile engine that had been used previously by John Coundley in his McLaren-Oldsmobile sports racer. This Traco-developed unit was a potent unit, and using four Weber carburetors the power output was initially 360-bhp from 6800 rpm. A standard Rover 2000 4-speed gearbox was fitted, as it was at the time the only available option, attached to a differential from a Jaguar E-Type. However, the standard gearbox proved to be very fragile, and during early tests Pierpoint experienced numerous failures. Later on, an American Muncie gearbox was purchased and fitted, allowing much more power to be driven through it, and thus providing all-important reliability.

After much work and testing the car was ready for its race debut, which came early in April 1970 as it lined up at Mallory Park in Leicestershire. A huge crowd was gathered at the lakeside venue for one of the track’s early season events, and with Pierpoint on-track, a number of expectant Rover directors had made the trip to watch. Despite a good early showing, the car ate its first Rover 2000 gearbox and retired. Just a few weeks later, with more Rover directors present, Pierpoint guided JXC 808D to victory around the fast Castle Combe circuit in Wiltshire. Winning outright was a great delight for everyone involved with the project and the future looked bright. The car continued racing throughout the season, scoring some success along the way—notably victory in the 100 Mile Saloon Car Race at Silverstone. By the end of the season, the Competitions Department was set on moving on with the Rover competition story, and so a new car was commissioned and JXC 808D was sold to Alec Poole who raced it, not quite in the same specification as Roy Pierpoint had driven it, to several successes in Ireland.

NEW CAR AND THE END OF THE ROAD

The Abingdon-based Competitions Department decided it should now build a Group 6 prototype car Rover P6 from scratch. Initially, it was thought that this car would just be for racing, but an eye was placed on the Group 2 rallying scene, as well. With international rallying again set for a 1970s boom, it was a market that Rover felt it should explore, and so work commenced with fresh enthusiasm. Bill Shaw was again commissioned to carry out the majority of the technical work in the early stages, with Abingdon staff adding the finishing touches to the vehicle prior to an official “roll out.” The car was presented in Leyland blue and white—a striking finish that caught the eye of all who saw it.

Work was completed on the car prior to the 84 Marathon de la Route at the Nürburgring, and was entered by the works for the event that was a direct replacement on the motoring calendar for the Spa-Sofia-Liege Rally, with which Abingdon officials had previous experience. Victory in the event in 1966, with an MGB and a 2nd-place finish with a one-liter Mini the following year, left the team responsible for the P6 with some optimism as they set off for Germany to take part.

Despite the optimism, the travelling Rover squad was really taking an untested and unproven car to the world’s most gruelling circuit with the expectations of it running successfully for 84 hours around the track! Hopes were high, however, and really the event was viewed as a test to compare the car against machinery entered by other manufacturers of that time.

Prior to departure, the car had only enjoyed a handful of test laps at Goodwood, and so found itself entering the lion’s den at the ’Ring. Under the watchful eye of Browning, Bill Price and Bill Shaw, the car was transported to Germany where it would be driven by Roy Pierpoint, Clive Baker and Roger Enever.

The Marathon was contested over the combined north and south loops of the ’Ring, giving each lap a distance of 19-miles. Practice for the Rover team was kept to the bare minimum to preserve the car—its long-term reliability was an unknown quantity! Each driver within the Rover camp was granted just one lap in practice, but apart from a small concern with a vibrating and bouncing prop shaft, everything went well.

Clive Baker took the start in the P6 at 1:00 in the morning and with the South Loop of the ’Ring returning back along behind the pits, everyone in the Rover squad was keen to see how Baker was shaping up before heading off into woods and onto the full Nordschleife. Those present were in for a shock as Baker’s V8 rumbled by in the lead! Baker held a strong advantage, and as he disappeared off for a full lap of the ’Ring the rest of the field arrived, headed by the factory-supported Porsches.

The Rover’s lead at the completion of the first lap had increased. The worry from the pits was that, despite a limit of revs to just 4500, Baker was going too quickly. A quirky regulation in the event stated that the average speed recorded in the opening hour had to be recorded in the final 84th! With Baker, Enever and Pierpoint running to strict team instructions the mighty Rover ran trouble free for 16 hours until the prop shaft vibration that had first appeared during practice returned. The rattle increased, and the car was reluctantly retired from the event to avoid further damage, or a crash into the track’s daunting shrubbery. At the time of its retirement, the Rover P6 held an amazing lead of over three laps—a distance of more than 50-miles!

The Rover P6 V8 made a great first impression in Germany. It was a true talking point at the track and the European media raved about the Leyland giant. Things looked good….

However, back in England, things didn’t look so good. Dark clouds were forming over the Competitions Department at Abingdon and the Leyland management took the decision to its doors. The Rover P6 project was over. The fourth stage of Browning’s plan was never even considered. And as for any future potential, well, that remains unknown.

Those involved with the Rover P6 project know full well that valuable information was thrown away, and later, when the Rover V8 made a return to competition via the Rover 3500 SD1 touring car projects and the TR7 V8 rally work had to start all over again on a fresh chapter before the “old” Rover V8 disappeared from frontline competition forever.

A BIT OF AN ANIMAL

I must admit I have always been a fan of British cars! Born in 1970 I am a child of the British Leyland era, and when asked to drive the V8-powered Rover P6 I must admit to being quite excited. This car oozes ’70s goodness, and sitting quietly in one of the cavernous garages of the new Silverstone Wing pits complex it looked like a resting wild animal. Now owned by Ian Giles, the car has been lovingly restored and returned to competition, having already been in action at both Donington Park and the Silverstone Classic. It was at Silverstone that I was handed my chance to climb behind the wheel of this mighty beast and put it through its paces.

Settling into the driver’s seat I couldn’t help but think just how period the inside of the car feels. The Rover carpet set, fitting or not fitting, in all the right places is so typical of a Leyland-manufactured car of the ’70s, and the easy to read speedo and dials were placed high on the leatherette-clad dashboard. Settling behind the wheel, I was given instructions on how to fire up the car’s mighty Traco-badged engine, and I had previously observed a fine-looking side-exit exhaust on first inspection of the P6. As I pressed the starter button, I knew I wouldn’t be disappointed by the noise it would emit and I wasn’t! The V8 burst into life with a massive roar, and a blip or two of the throttle boosted my love affair with the car even further..

I love large steering wheels and the P6 has a traditional 1970s-style wheel fitted. It allowed me to wrestle firmly with the car as the rear end, on chilly slick tires, continually wanted to break away. Remembering the words of my good friend Neil Cunningham, a racer who has driven a V8-engined car or two in his career, I should make sure to keep some throttle in reserve just in case the back of the car becomes a little too excitable. “If in doubt, floor it!” are great words of advice for a driver of a rear-wheel-drive car. More throttle and not less is the only way to control a car in a slide, and this Rover is a car that feels like it wants to twitch! However, the large slick tires did give it a feel of stability at a time when things were getting potentially interesting behind the wheel!

Throughout my test the constant factor was the beauty of the noise. The V8 burbling as a constant companion as I changed up and down the gears through the four-speed box with its gear lever sitting high out of the floor and within easy reach from the steering wheel. A blip of the throttle and a double-declutch down the box, a requirement that enhanced my audio pleasure from within the cabin and for those watching from trackside.

Aiming toward apexes of the Silverstone track, the car found them no problem at all as I began to push harder. And, with Silverstone’s long and fast straights ahead of me, I knew I was in for some fun!

The car, in truth, is a bit of an animal! Conceived with the notion from Peter Browning that “there is no substitute for sheer horsepower,” this car was built to breath fire. It was suited to high-power venues such as Mallory Park and Castle Combe. It is easy to see why Roy Pierpoint could win in Wiltshire; the former airfield track in its original unadulterated format was supremely fast. The V8 would have lapped up every yard of the track with ease, and here at Silverstone it felt like it wanted to as well.

At the Nürburgring, the P6 showed its mettle against other major manufacturer entries, and if the project had not been ended at the end of 1971 this car would surely have been better remembered than it is today. The Rover P6 racer survives, but is mostly forgotten. The latter success by the TWR Rover SD1 cars are remembered as the biggest success for the Rover marque, but this car essentially started it all. I am proud to have driven this wild machine, and I can tell you I really enjoyed it!

SPECIFICATIONS

Body: Rover P6 V8

Chassis: Lightweight body on original Rover P6 chassis with extended fenders and wheel arches

Engine: Traco-Oldsmobile

Displacement: 4300-cc / 262 cubic inches

Power: 360 bhp

Transmission: 4-speed Muncie gearbox

Brakes: Four-wheel ventilated discs

Wheels: 10-inch Minilites / Dunlop Tires

Acknowledgements / Resources

I would like to thank Ted Walker for helping to arrange my drive in this Rover so that I could compile this Profile, and the car’s owner, Ian Giles, for kindly handing me the keys and allowing me to climb inside! I would also like to thank Peter Browning and Roy Pierpoint for their recollections, which have allowed me to chart the competition history of this car.