There’s no middle ground with A.J. Foyt, no compromising your feelings. You either love him or hate him. You either think he’s the greatest racecar driver who ever lived, or the most over-rated, or, perhaps like Chris Economaki, the luckiest guy who ever put on a racing helmet.

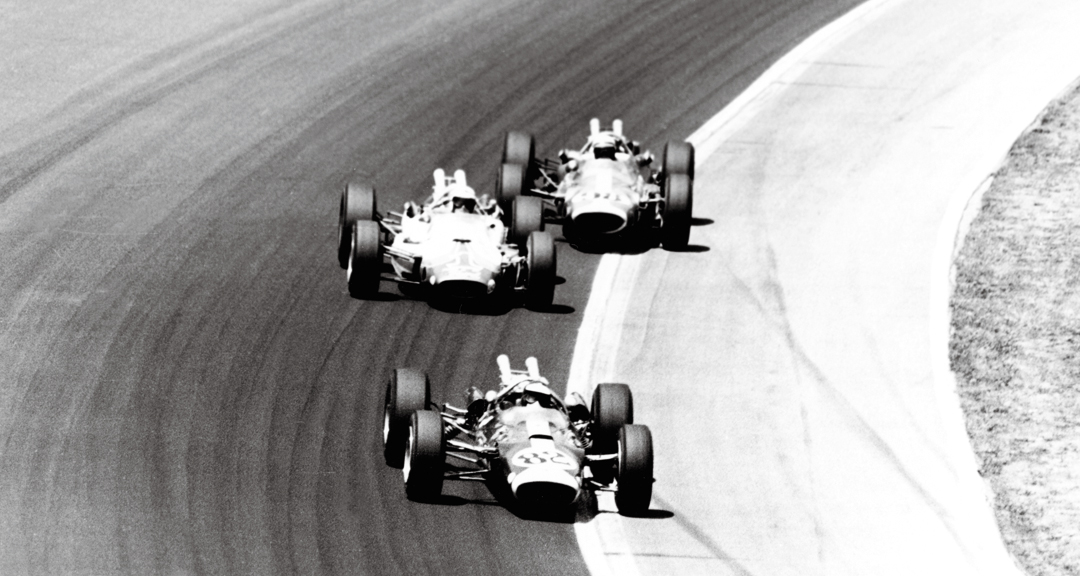

Whatever your feelings, this story is not about Foyt—not directly—but about the racecars built in his Houston shop between 1966 and 1981, cars that delivered 25 champ car wins, two Indy 500 victories, two national championships, and one very serious crash. The cars are the Coyotes and, as we shall see, reveal quite another side of the legendary Texan.

Foyt liked to talk about how he built his own cars, and raced his own cars, seemingly going it alone against the big money teams—All American Racers, Penske, Vel’s Parnelli Jones, McLaren—with their legions of designers and engineers, a David-versus-Goliath image. Foyt indeed worked on his own cars—he valved his own shocks, for example. Usually, he was the first to arrive at the shop and the last to leave. He set the tone, and there was never a question of who ran the team.

Nonetheless, he did receive a lot of help from the Ford Motor Company—in the form of free engines and free parts—and, when it came to chassis development, free technical support from several Ford engineers. In 1970, when Ford pulled out of racing, they turned over to him the entire Indy engine program—patterns, tooling and over $200,000 worth of spare parts—for virtually nothing. According to one Ford engineer, Team Foyt was in reality a Ford factory team. Of course, other teams using Ford engines received factory assistance, but none to the extent that Foyt did.

Photo: Indianapolis Motor Speedway

Two Ford engineers key to Foyt’s success were an unsung German named Klaus Arning and a soft-spoken Louisianian, Bob Riley. Arning was a suspension guru instrumental to Ford’s Le Mans program, and the designer of the 427 Shelby Cobra’s rear suspension. He spent a lot of time working with A.J. Riley and was among the first chassis designers to do extensive wind-tunnel testing. As early as 1969, he was flirting with ground effects, but more about that in a moment.

First, some debunking. The Lotus 38—the basis of the first five Coyotes—was not that great of a racecar. Sure, Jimmy Clark dominated the 1965 Indy 500 driving one, but the fact is the car never won another race, despite the efforts of Dan Gurney, Lloyd Ruby, Al Unser, Joe Leonard and A.J. himself. In 1966, Mario Andretti drove a Lotus 38 in practice at the Speedway and afterwards, in so many words, told his team to dump it in the Wabash. His Brawner-Hawk—with its lower center of gravity and superior grip—was four mph faster at the Speedway.

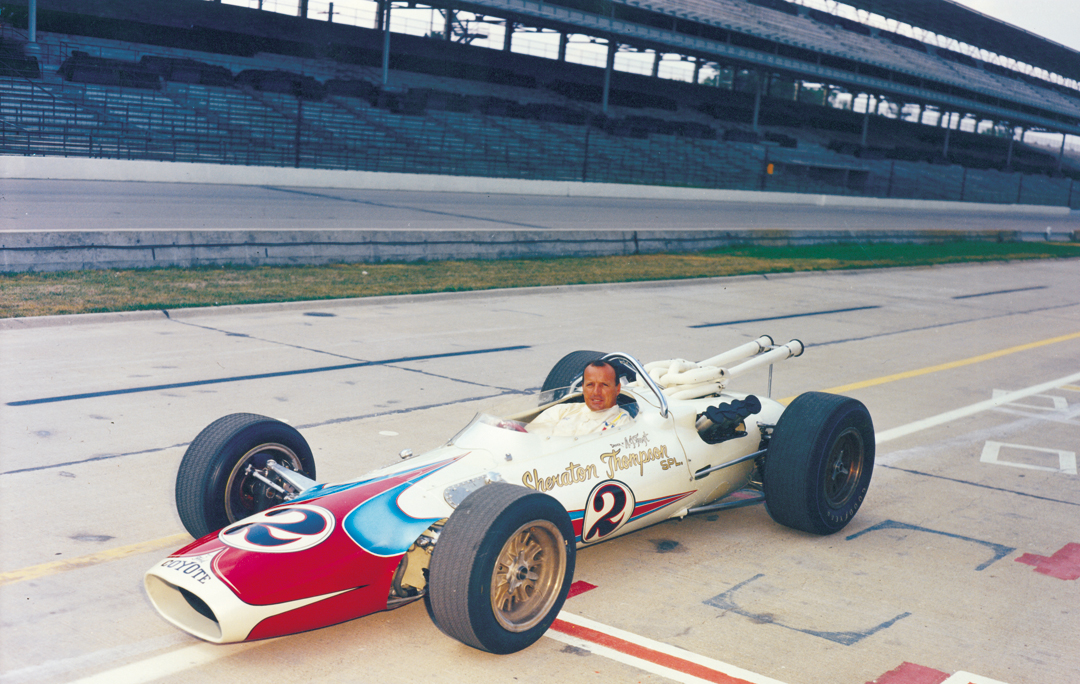

Like a lot of people, perhaps Foyt was dazzled by Clark’s 1965 performance. During the race, the Scot passed him easily to take the lead and eventually put him down a lap. For 1966, Foyt purchased two Lotus 38s and made a copy, which was the first Coyote (the “Coyote 38” as Colin Chapman put it). Then disaster struck. At the Speedway, the Texan crashed the Coyote in practice and in the race he and teammate George Snider crashed both Lotus 38s. Clark, the fastest of the Lotus 38 drivers, complained of handling problems most of the month. In the race, he spun twice and was fortunate to finish 2nd. After the race, Foyt purchased Clark’s Lotus and, a week later at Milwaukee, put it in the wall. The car caught fire and he suffered burns on both hands.

Had Foyt backed the wrong horse?

“There were a lot of issues with the Lotus 38,” says Dan Jones, a Ford engineer who worked closely with several Ford-powered teams in the 1960s. “With the asymmetric suspension, all the suspension arms were of unequal length, from right to left. Wheel travel versus spring travel, from side to side and front to rear, was unique on all four corners, so your wheel rates were very difficult to control.”

Eventually one of Foyt’s cars arrived in Dearborn for analysis. Bob Riley, who today with his son, Bill Riley, operates Riley Technology, said recently: “I remember when we got in Foyt’s Lotus. The bump-steer was terrible. We could get rid of bump-steer in front, but on the independent rear cars, we didn’t know exactly know how to get rid of it. That’s what drove a lot of them, that rear steer, which was really quite bad.”

Riley continues: “Ford had just gotten into the computer age, you might say, when we did the Le Mans cars. I think we went through 60 or 70 computer runs and almost by accident we found out how to get the rear steer out. We put castor in the rear uprights. I really think it was a big element in Ford beating Ferrari at Le Mans.”

Foyt went winless that year. For 1967, he built a second Coyote, updated the 1966 Coyote for teammate Joe Leonard to drive, and changed team colors from the white, red and blue livery he was known for, to a Ford color, warm poppy red (as used on the 1965 Mustang). The Ford blue oval began appearing on his cars as well. That May at Indianapolis, his old nemesis, Parnelli Jones, stole the headlines and very nearly the race driving Andy Granatelli’s turbine car. Leading easily, Jones dropped out three laps from the finish, handing Foyt the lead and his third Indy 500 victory. Two weeks later, driving the Ford Mark IV, Foyt and Gurney won the Le Mans 24 Hours. By the end of the season, the Texan was national champion, capping a remarkable year.

Foyt’s biggest challenge over the next three years was not Andretti or the Unser brothers or some new rising star, but rapidly advancing technology. In 1968, it was Granatelli’s turbines again, this time powering three of Colin Chapman’s wedge-shaped Lotus 56s—and turbocharging. The turbines again got all the headlines, but it was destined to be Bobby Unser’s year. He won the 500 and the national championship driving a turbocharged Offy-powered Eagle. Running a normally aspirated engine, Foyt was an also-ran until late in the season, when he won two races, the latter powered by a turbocharged Ford.

Photo: Indianapolis Motor Speedway

In 1969, it was four-wheel-drive that had teams scrambling. In 1970, it was aerodynamics, with cars assuming lower, wedge-like shapes to increase downforce. Foyt seemed not to notice. Each year, he made updates to the basic Coyote design: increasing fuel capacity from 60 to 75 gallons to meet the needs of the thirstier turbo-Fords; changing and strengthening the tub around the engine area; and having Klaus Arning down from Dearborn to design new uprights and relocate rear suspension pick-up points to take advantage of ever-widening tires.

At one point, Ford presented the Texan with a two-speed automatic transmission for his exclusive use. He might have run it had turbocharging not come along and negated its advantage. The Coyote sprouted various aerodynamic devices but, as late as 1970, still bore the same basic cigar shape of the original Lotus 38 Len Terry had designed over the winter of 1964–65. The car was still quick: Foyt put it on the front row at Indy in both 1969 (on pole) and 1970. But the Coyote’s only win those two years was at the inaugural California 500, in 1970. Foyt’s teammate Jim McElreath got the victory.

Photo: Indianapolis Motor Speedway

Foyt needed a change and knew it. Ford pulled out of racing in 1970, so he asked Arning to recommend a designer, someone who could deliver the complete package—suspension, chassis, aerodynamics. Enter Bob Riley, late of Kar Kraft and now with Ford styling. Riley had been moonlighting, designing Formula Vees and the like. Ford gave Riley a month off to go to Houston, set up his drawing board, and design Foyt a car for the 1971 season.

The first wholly new Coyote in four years was wedge-shaped and looked very much like the model Riley had been toying with in the wind tunnel at Ann Arbor in 1969. Under certain conditions, the model had developed ground effects, but Riley wasn’t sure how to harness it, not yet anyway.

His immediate concern was Foyt. Sure, the Texan had bought his design, but there was still the matter of whether or not Riley’s car would deliver where it counted—on the track.

Riley: “I made one mistake. I wanted to get the frontal area down and made everything very narrow, including the cockpit. When A.J. first tried out the car, there wasn’t room for him to shift gears. In other words, his hands were straight out, holding the steering wheel, but he couldn’t move his right arm back to shift the gear lever.”

Riley didn’t know what to expect next. The Texan might come storming out of the cockpit and punch him, or at the very least give him a good tongue lashing. For a second or two nothing happened. “I looked at him, and he looked up at me,” says Riley. Then, the Texan reached over with his left hand and grasped the shifter, and said, “Wait a minute. I’ll shift with my left hand.”

“I’ve worked with so many drivers since then who have to move the shifter a quarter inch here, a half inch there,” says Riley. “It was just remarkable that he ran like that, shifting with his left hand crossed over. I still can’t get over that.”

Working for Foyt meant working with some of the finest fabricators in the business, men like Luigi Lesovsky and Eddie Kuzma. “Up to then, I had to watch what I’d draw or people couldn’t build it,” Riley says. “With Eddie, anything I could draw he could build. On the 1971 car, we weren’t quite sure of the nose shape, so I think he built three of them out of aluminum—they were just perfect—and we went with the one that worked best.”

The 1971 Coyote was a good car, a quick car, and garnered Foyt his first champ car victory in three years, and a solid 3rd place finish at the Speedway. However, with the arrival that year of the ground-breaking McLaren M16, it came one year too late.

The 1971 Coyote was a good car, a quick car, and garnered Foyt his first champ car victory in three years, and a solid 3rd place finish at the Speedway. However, with the arrival that year of the ground-breaking McLaren M16, it came one year too late.

Riley proposed a new car for 1972, with side-mounted radiators. The design bore a striking resemblance to Gurney’s 1972 Eagle. “It was built on the Gurney concept, you might say,” says Riley. “We did use Eagle rear uprights and Eagle transmission mounts, but the tub was built in Houston, to my drawings. If you saw both cars side by side, you would see the difference.” Development on the 1972 Coyote was set back when Foyt was injured in a sprint car accident and missed four races at midseason. At Ontario in September, he led from the start until sidelined by a broken differential.

Riley was not satisfied. Unlike the turbo-Offy that most teams were now using, the turbo-Ford presented a very large front profile that restricted maximum airflow from reaching the bottom side of the rear wing. After wind tunnel testing various models, Riley proposed a new car for 1973, one with a very low and wide chassis and a tight aero-package around the engine that required rerouting the engine’s bulky induction system. The design didn’t come easily.

“I went down for a month in his shop,” says Riley. “When I was finished, I was just not happy with anything, so on the last day I wadded it up and threw the whole thing away. I told them I was going to go back and do it at home. I guess along the way I got the idea of the very low tub. I went home and did it at night and then sent Foyt the drawings.”

Photo: Indianapolis Motor Speedway

There was something unique and groundbreaking about the 1973 Coyote: it had skirts. Riley: “We were looking for more downforce. I had a model we were running at Texas A&M, and I was just trying different things on the model, and I tried bringing the sides down, and that picked up some downforce in front.”

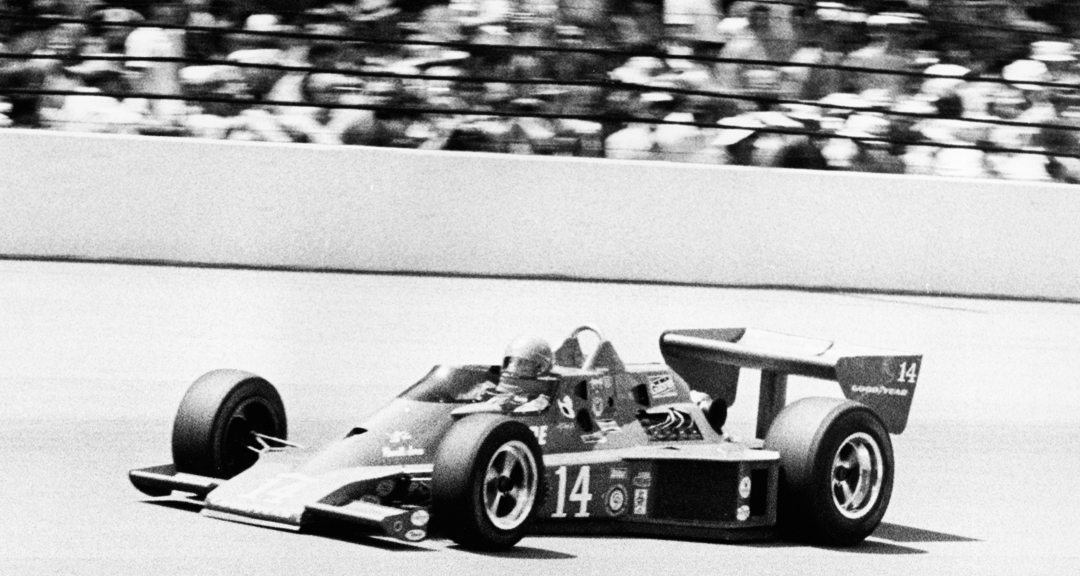

Foyt tested the new car at Phoenix and noticed the difference immediately. That summer, he won two races, his most wins since 1968. Weight distribution, however, was not ideal. For 1974, the radiator was moved to the front, and that solved the problem. Foyt was on top again, the man to beat, and the Coyote widely copied. The Texan put the car on pole at Indy in both 1974 and 1975. In 1975, he won seven races and the national championship, his sixth.

About working with Foyt, Riley says: “I did do the drawings; that’s true. At the time, I had designed enough cars to know that I had to work with someone who really knew what he was doing. I think had I designed an Indy car for someone else—for just an average team—I fiercely doubt it would have worked. I’ve worked for a lot of drivers over a half century, and he really was the best.”

About testing, Riley says: “What he would do with a new car at Indianapolis, he would usually take one slow lap, and then kind of take a fast lap. Then he’d come back with a big grin, and he’d say, ‘Oh, I almost took off in Turn 1,’ or, ‘I lost steering in Turn 2.’ He’d make about 10 changes and go out again. ‘Well, that was better, but I don’t know,’ he’d say. But he always had a good time doing it. Usually, by the second day, the car was sorted.”

Photo: Indianapolis Motor Speedway

For 1976, Foyt and Jack Starne, his chief mechanic, modified Riley’s design. The new car looked similar to the previous model, but had several detail changes. Foyt finished 2nd at Indy that year, and in 1977 won his fourth Indy 500. He raced the Coyote throughout 1978, and in 1979 split driving time between it and a Parnelli-Cosworth. Foyt drove the Coyote to its final victory that year, at College Station, Texas, in his own backyard, so to speak.

Foyt raced a Parnelli full time in 1980. In 1981, he returned to building his own car. Once again, Riley was called to Houston. Ground effects were by then standard in F1, but still new to Indy. The new Coyote had a lot of downforce. “We really didn’t know how to handle it,” Riley admits. “We had no idea you had to go so high with the springs, how stiff they really had to be. To make the car work, we actually ended up cutting holes in the bottom of the sidepods to let it breathe air out.”

Says Starne: “If we really had understood what the car needed, we would have been on Broadway. The car was mighty good and mighty fast, but then it could have been so much, much better.”

Foyt put the Cosworth-powered Coyote on the front row at Indy (third fastest) and in the race finished 13th after being slowed by mechanical problems. It was the last time a Coyote would compete at the Speedway. That summer, the Texan crashed heavily at Michigan, breaking an arm and suffering a concussion. Foyt would return to race another day, but the Coyote era was over.

Photo: Pete Luongo

Starne: “We weren’t prepared to get into the car manufacturing business, because we weren’t selling them. We were just doing them for our own race team. By then, you could buy a car a lot cheaper than you could build one.”

The Coyote’s lasting legacy, perhaps, is this: No American chassis-engine combination has won the Indianapolis 500 since Foyt’s 1977 victory, a source of obvious pride for the Texan.

No one at A.J. Foyt Racing is sure how many Coyotes were built over the years. When asked, Indy historian Donald Davidson guessed the number was eight. Even A.J. doesn’t recall. He never assigned serial numbers (or, for that matter, chassis types). Adding to the confusion is the fact that at least one and possibly two Lotus 38s were rebuilt in Foyt’s shop and variously competed as both Lotuses and as Coyotes.

The likely number is 12. Here’s the reasoning:

Most years, one car was built and raced by the boss. Foyt’s teammate drove the previous year’s car, which along with the primary backup car was rebuilt and brought up to current model spec. A few examples:

In 1967, Foyt drove a new Coyote, while Leonard drove the 1966 car. The Coyote McElreath drove to victory in the 1970 California 500 was a 1969 model. On the other hand, the Coyote mechanic/driver Crockey Peterson campaigned in Formula 5000 started life as a Lotus 38 (the very chassis Clark drove to 2nd place at Indy in 1966 and that Foyt crashed at Milwaukee one week later). The Coyote Mel Kenyon drove for owner Lindsey Hopkins in 1970 was a 1966 Coyote. Bottom line: between 1966 and 1970, if Foyt built one new Coyote each year, the total for this period is five.

For 1971–81, the numbers are better known. In 1971, the year Foyt switched to a Bob Riley–designed Coyote, two cars were built. In 1972, one was built. In 1973, two Coyotes were built and raced through the end of 1975. In 1976, one was built, plus enough spares for a second car that was never built. Foyt raced this car from 1976 up to winning the 1977 Indy 500, when the car was retired. After this, he raced one of the 1973 cars through the end of 1979. The final Coyote was built in 1981. Counting the cars built 1966–70, the total is 12 Coyotes, 13 if you count spare parts.

Where are the Coyotes today? Three are in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum: the 1967 Indy winner, the 1970 California 500 winner, and the 1977 Indy winner. The three remaining Coyotes from 1966–70 were sold (one and possibly two went to Lindsey Hopkins) and today are presumed privately owned. Of the two 1971 Coyotes, one was recently restored. The whereabouts of the other is unknown. The 1972 car was sold and crashed in the 1974 Indy 500 (driven by Rick Muther). Recently it, too, was restored. Of the two 1973 cars, one is owned by the Jim Robbins family (a longtime sponsor). The second is presumed to be privately owned. The spares for a second 1976 car were sold and are reportedly in the Indy Museum basement. The 1981 Coyote is thought to have been restored and privately owned.

Roger Penske may have gotten all the ink for his immaculately prepared racecars, but for the month of May no one could top A.J.’s Coyotes for sheer mechanical elegance. Granted, the original Coyote is a Lotus 38 copy, but Foyt made the car his own. Where the Lotus’s fuselage is all rivets and seams, the Coyote’s skin is glass smooth and unbroken. The tapered nose and upswept tail—the result of extensive testing—gives the car better proportion than did the original nose and tail of the Lotus 38, as if someone had taken an airbrush to Len Terry’s design and given it flair. Chrome? If it wasn’t painted warm poppy red, Foyt chromed it.

Riley’s 1973–79 Coyote looks more purposeful and menacing than the 1966–70 Coyote but, of all the Indy cars built and raced in the 1970s, none had a more striking profile. Look how Foyt resolved the bulky intake manifolding. Not even the ex–flower shop owner (and ex–Foyt chief mechanic) George Bignotti could do anything with it. The big Ford four-cammer with all its plumbing—so out of harmony with the Lolas, Colts and Eagles of the day—is neatly integrated into the Coyote’s overall shape.

Also, the Coyotes were never the rolling billboards that so many Indy cars were then and are today. The sponsor’s name never took center stage on Foyt’s cars, was never gaudy but small and in harmony with the overall appearance of the car. Face it. Foyt had taste, and not just for Texas chili.

Foyt did get a lot of outside help, especially in the beginning. Most top teams did, from one source or another. It’s what he did with it that counts. His accomplishment—building his own cars, developing his own engines, doing all the testing and racing and winning—was monumental. Few have attempted as much, and none with Foyt’s success. It’s unlikely anyone ever will.