1978 Eagle DGF

There is a historical trope in the racing world, which suggests that a talented craftsman could build a simple, small displacement racecar—like a Formula Ford—and his prototype’s success would catapult that individual into becoming a major racing car manufacturer, eventually reaching the pinnacles of the sport, F1 and the Indianapolis 500. Names like Colin Chapman (Lotus) and Eric Broadley (Lola) spring immediately to mind. However, the tale of the Eagle DGF is the exact opposite of that story! After building a racing empire founded on Grand Prix and Indycar victories, American racing icon Dan Gurney elected to go the other way. Gurney’s Santa Ana, California-based All American Racers (AAR) was building race-winning Indycars and F5000 cars, but Gurney thought there might be opportunity in expanding his offerings into the more “mass market” world of entry level Formula Ford. According to Gurney, “There was a time there, where we thought that Formula Ford was going to go somewhere and it was one of the steppingstones for up-and-coming young men, and we thought we’d like to put our version into the arena.” AAR had the talented design staff, the manufacturing facilities and expertise, so why not diversify and grasp a larger share of the market, while at the same time, creating a pipeline for young drivers to come up through the ladder. If all went well, ideally one day they would buy and race more sophisticated Eagles. It was a logical move, yet oddly, it didn’t go entirely as planned.

While Gurney and AAR certainly had the staffing and resources to build a Formula Ford, what they lacked was an in-house “FF expert,” someone with a wealth of FF experience who could both drive and develop the car. While, in retrospect, Gurney is unclear who first passed the name on to him, it may very well have been fellow constructor Ray Caldwell, who had enjoyed the fruits of a talented young driver named David Loring.

Loring

David Loring got his start as a teenager in Formula Vee, in 1969. Loring soon caught the attention of both future automotive journalist Gordon Kirby and the up-and-coming Caldwell Formula Ford concern. With Kirby lending assistance, Loring raced for Caldwell in its D9 Formula Ford and racked up an impressive string of more than 30 race wins and four separate FF championships, in 1970 and 1971. With the help of his mechanic friend Chris Wallach, Loring prepared his own car out of the quintessential barn behind his parents’ home in Concord, Massachusetts.

The 1972 and 1973 seasons saw Loring travel to the UK, initially with the intention of racing in F3, but ultimately having to settle for more Formula Ford competition. Despite the UK’s elevated FF talent pool at the time, Loring was able to notch up five wins and a long-standing track record at Mallory Park. However, eventually funding dried up and Loring headed back home to more FF racing, as well as the odd Formula Atlantic ride. However, a phone call late in 1976 would forever alter the arc of Loring’s racing life.

According to Loring, “I was sitting at home in Massachusetts watching a hockey game and the phone rings and some voice I didn’t recognize says, ‘Is David Loring there?’ When I said, ‘This is David,’ the voice says, ‘This is Dan Gurney.’ And I go, ‘Yeah, right!’ and hung up. So five minutes later it rings again and it’s the same voice. So, I listened for a minute and realized it really was Dan Gurney, and he wants to know if I want to go to work for him, to help design and build this Formula Ford. Three days later I was in California with everything I owned in the back of a truck!”

Hatching an Eagle

The task of designing what would become known as the DGF (Dan Gurney Ford) was given to AAR’s junior designer John Ward. Having only worked at AAR for a year under designer Gary Wheeler, the DGF was not only Ward’s first complete AAR design; it was also his first complete racecar design! Having raced in FF himself, Ward sat down in October of 1976 and sifted through the SCCA’s rulebook for any technical advantages that AAR might be able to exploit. While needing to work to a specific price point, Ward, assistant designer Ron Hopkins, Loring and Gurney agreed on two critical aspects of the DGF’s design. The first was that the DGF needed to be designed with straight-line speed as its primary goal.

Due to Formula Ford’s limited horsepower, 1600-cc engines, the team determined that straight-line speed should be optimized, since at most tracks the cars were running predominantly flat-out, with slipstreaming duels quite common. Therefore, the DGF would be designed as a narrow, “arrow-like” racecar to minimize aerodynamic drag and maximize top speed. Loring commented at the time, “People give us static for not having side radiators and a wide nose on the Eagle, but all we’re interested in doing is making a very little hole in the air. At most of the tracks we run the cars are so even in suspension geometry, in the way they put the power down, that it seems like the only way you can try and break away from somebody is on your wind penetration, your straight-line speed. I just don’t agree that you need a lot of trick aerodynamics on these cars.”

The second key design feature was ease of maintenance, a concept near and dear to Loring’s heart, “A lot of the stuff I wanted was…like to be able to change an oil pump without pulling the engine, because with some—particularly English—Formula Fords you had to lift the engine up to do that. I had raced all kinds of different FFs, so I knew what things were real important as far as ease of maintenance and stuff like that.”

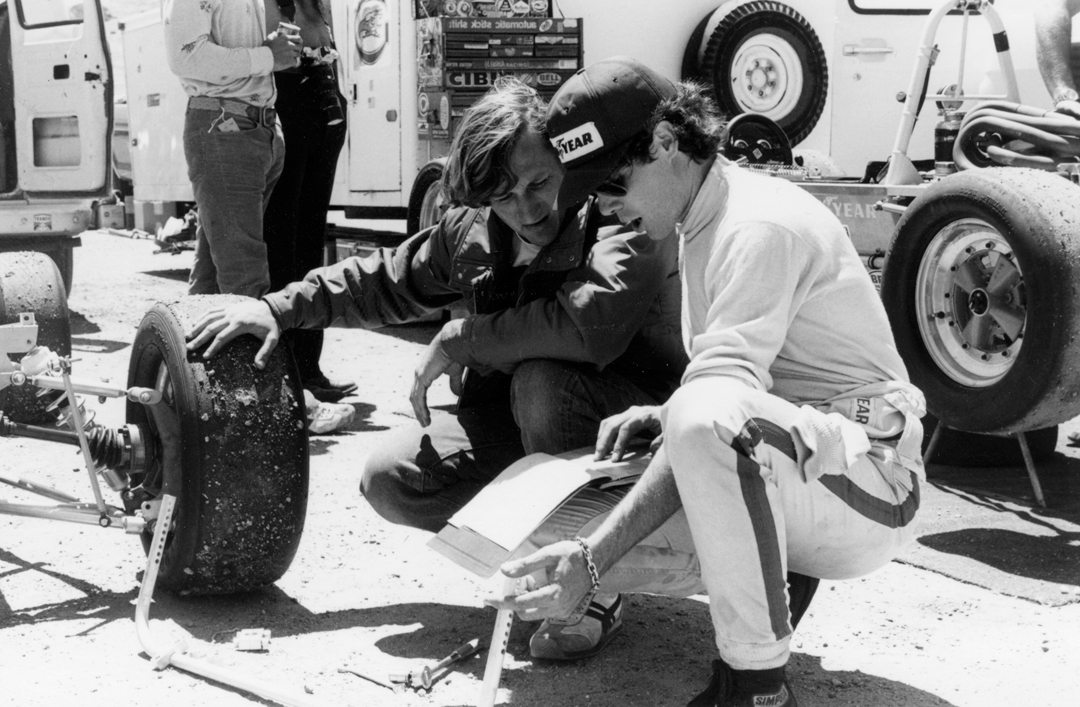

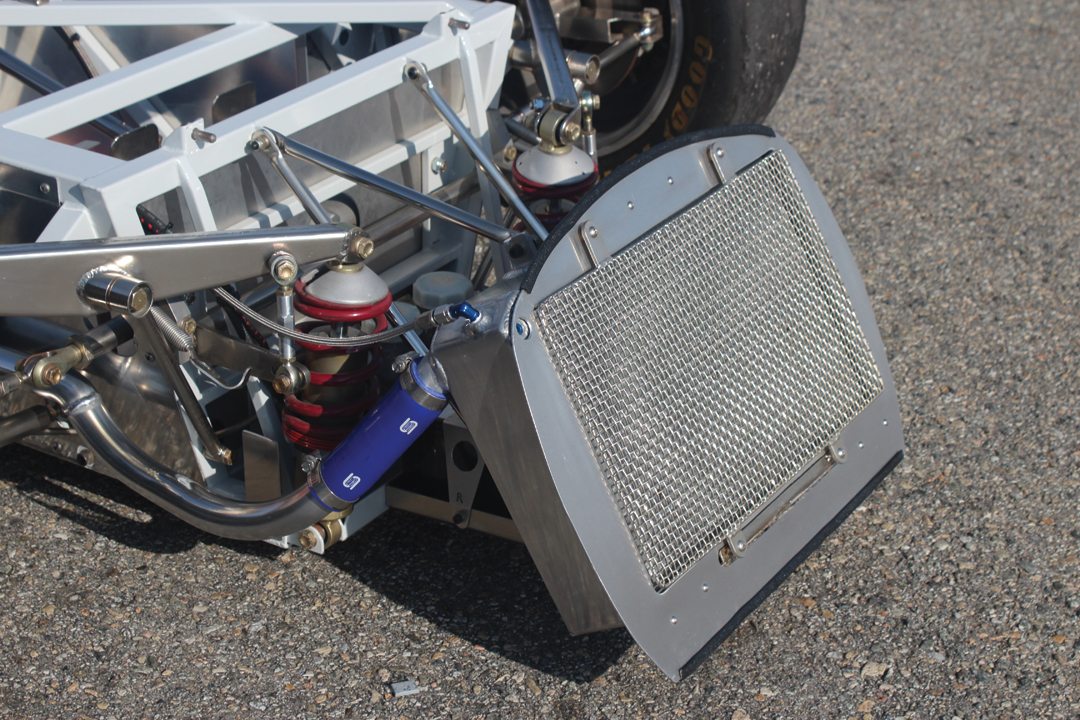

Photo: Casey Annis

In the end, Ward penned an extremely narrow track (54-inch front, 52-inch rear) space frame made with square tubing (for ease of repairs compared to round) that was Heliarc welded (instead of nickel-bronze brazed) for strength. The 95-inch wheelbase frame received unequal length A-arms, with inboard coilovers at the front to optimize the airflow over the front suspension. At the rear, the DGF had a fairly conventional, for the time, lower wishbone, with upper lateral link and radius rod setup connected to a cast upright. Rounding out the rolling chassis was a Schroeder rack and pinion steering unit, Lockheed 9.5-inch cast iron disc brakes and a set of Gotti 5.5×13-inch composite rims.

Under the watchful eye of AAR fabrication wizard Phil Remington, Chassis 001 was built over the winter of 1976 and then handed over to Loring for assembly. Loring installed a regulation, Charlie Williams-built, 1600-cc Ford Kent engine mated to a Hewland Mk9 gearbox. Clothed in a tight-fitting fiberglass body, with a nose perhaps more reminiscent of an anteater than an Eagle, the DGF was carted out to Willow Springs Raceway on May 2, 1977, for its first test, though the car’s first race would come just a few weeks later.

Learning to Fly

Loring and the Eagle made their SCCA race debut at Riverside Raceway on May 28-30, 1977. This was a true first for both the DGF and Loring, as Loring had never run at Riverside before! Despite his inexperience, Loring put the Eagle 6th on the grid for the National race and by lap 6 was leading! Sadly, in the closing laps a competitor made a diving pass attempt on Loring, going into Turn 6, badly damaging the Eagle. Loring later attested to the DGF’s strong, well-built frame as having saved him from serious injury.

After the damage was repaired, 001 was taken back out to Willow Springs for more testing. Ward recalls, “David could go through Turn 9 flat out, which in those days was edgy, but good. You could see that every now and then though, he would get it a little wrong and have to make some corrections. So we were trying to figure out how to make a long tail to stabilize the back end a little bit. There were other cars that had long tails, but they were wide and flat—ADF came to mind—so Dan said, ‘Why don’t we make something like half a pipe, round, with a Gurney flap on the back?’ So that’s what we did. Rem rolled up a piece of aluminum and we riveted it onto the fiberglass, put a Gurney flap on it and took it out to Willow and did an A vs. B test with it, and David said Turn 9 was ‘easy now, I don’t even have to think about it.’”

It’s important to note here that while Loring had the support of AAR in terms of the DGF’s devleopment, this really was not a “fully supported” factory race effort. Loring, would single-handedly tow the Eagle to the track behind his pickup, wrench on the car himself, race it and then haul it back to Southern California. This reality was a far cry from the disinformation campaign waged by Loring’s competitors.

While Gurney had seen an opportunity to enter the FF field, his competitors—who had obvious vested interests in not seeing AAR carve out another slice of the FF pie—were portraying this as the “Big Guys” coming in to dominate the category and make everyone’s cars obsolete. Ironically, these rumors were being spread by some of the biggest factory teams from their motor homes and large encampments, while Loring struggled to single-handedly run his car! Realizing that he needed to focus on driving at the track, Loring convinced engine builder Charlie Williams to start accompanying him at the races, starting with the next round.

The car’s next outing was at Laguna Seca, on June 24-26, for another SCCA National. But with little time to figure out the Eagle’s ideal setup and with Loring again having never driven the track, the best he could do was to qualify 12th and finish 5th.

At Riverside, on the July 4th weekend, Loring qualified 6th for the National event, and despite a lack of power from his engine, managed to salvage the car’s first podium finish with a 3rd place. Two weeks later at Pueblo, Colorado, Loring qualified the Eagle 2nd on the grid and went on to finish 2nd in the National. It looked as if Loring and the DGF were getting tantalizingly close to that elusive first win.

First Win

On August 7, Loring and the DGF unloaded for the Regional and National races at Hallett, Oklahoma. In Saturday’s Regional, the DGF qualified 2nd and easily led the race. Yet strangely, on the last lap, Loring pulled into the pits. He recalled, “On the last lap of the Regional, I had like a 5- or 10-second lead and I pulled into the pits. I called Dan that night, and I told him that I’d pulled in so that we wouldn’t win the Regional…and he went fuckin’ coo-coo! So, I said that I wasn’t going to go around with everybody saying that the first race the car won was a Regional, because the guy couldn’t win a National with it. He didn’t like that, but we won the National the next day, so it was OK.” In fact, not only did Loring handily win the National, he also claimed the pole, the fastest lap and knocked 1.1 seconds off the track record set by Bill Henderson just the week before.

Subsequent races included: Elkhart Lake, where despite a blown engine in qualifying, Loring was able to charge back through the field to finish 6th; Nelson Ledges, where a broken stub axle in qualifying left him only 41st on the grid, but found Loring posting a new FF track record as he passed 10 cars on the first lap; and a 3rd-place finish at Phoenix.

The grand finale for the 1977 season was September’s SCCA Runoffs at Road Atlanta. Loring recalled the weekend didn’t start off as planned, “I crashed it real big at the Runoffs the first year. Steve Shelton in a Lola ran me off the road. And, of course, my car, three corners were ripped off and the frame was twisted on the only DGF in existence, and he was in a Lola with Carl Haas, who had like 20 other cars there, so his car was back on the track that afternoon. Actually, I got into trouble there because I got out of my car and I went over to his car, and he was still strapped in, and I pulled up his visor and started smashing him in the face! We had to take it all down to the frame, and we put the frame on the ground and took a piece of guardrail and chained it to the back of the engine bay and drove a truck over it. And we took another piece of guardrail and chained it to the top front rail and kept twisting it until we got it reasonably straight. I should have won, but I just got caught out on the last lap. I had set it up so when I came onto the back straight I had a really good run on Dave Weitzenhof, but when I went to go by him, he moved over and put me into the grass. I didn’t think people did that in this country! If that had been England, I would have expected it—and after knowing Weitzenhof, I would expect from him, too—but it caught me out, and I ended up hitting him, but not hard enough!” Loring would end up finishing 2nd to Weitzenhof.

New Year, New Teammate

Photo: Fickling Collection

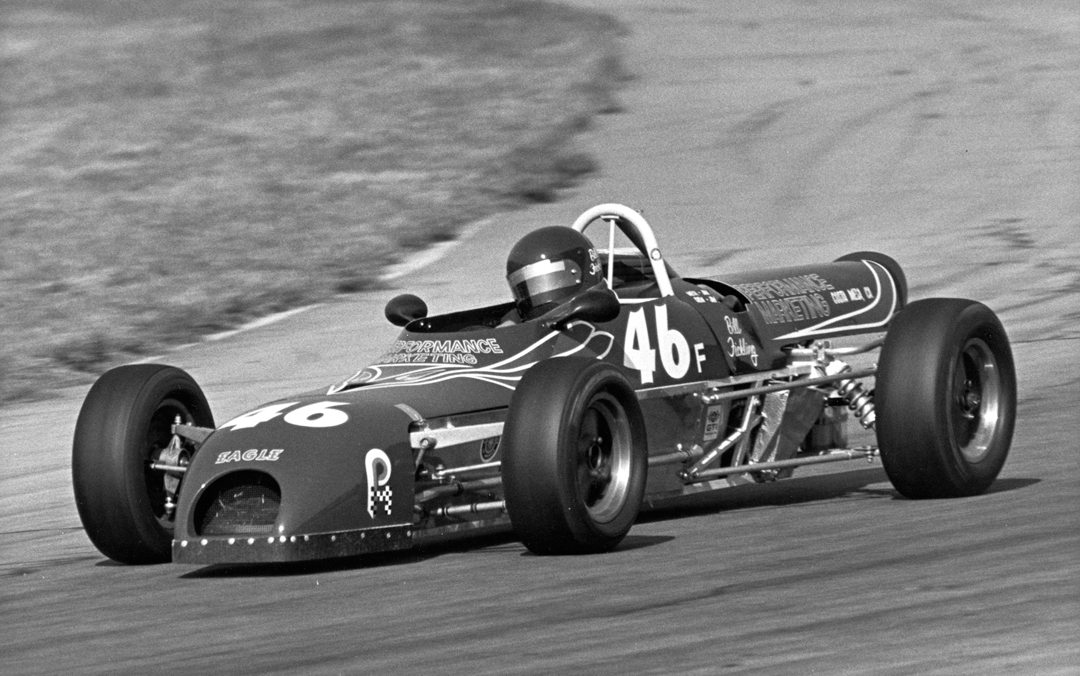

For the 1978 season, the badly damaged chassis 001 was retired and replaced by a new chassis, 002. Loring put this new chassis on the pole at Riverside in February and went on to win, following up that success with a 2nd at Phoenix in the end of February and another 2nd at Sears Point on April 9. But while Loring was demonstrating the DGF to be a winning combination, AAR was becoming concerned that if it was going to sell production examples, it had to prove that other drivers could be competitive in the car, as well. As a result, they reached out to an up-and-coming driver named Bill Fickling.

Fickling had already shown himself to be a fast FF driver. He started out with a LeGrand Formula C car in 1972, but by 1975 he was winning regional FF events in a Royale. Fickling really started to garner attention, in 1977, when he began racing a Lola 440, and then late that year bought Dennis Firestone’s Crossle and quickly began winning a number of Regional events. After a number of solid performances, Fickling found himself dicing with Loring at the front, which resulted in Loring calling Fickling in early April and asking him if he’d like to campaign a second Eagle DGF alongside him. Fickling was invited to drive Loring’s car at a National event later that month at Willow Springs, where he qualified 3rd and finished 3rd. After his Willow performance, Gurney offered Fickling an interesting arrangement.

While Fickling wasn’t to be a paid AAR factory driver per se, AAR offered to sell him a DGF (Chassis 003), for whatever he could get from selling his Crossle. Then he and Loring would work together at the races as teammates, though the business and financial side of Fickling’s racing would be his own affair. Fickling jumped at the opportunity and quickly found himself at AAR’s Santa Ana shop, working side-by-side with Phil Remington on the construction of Chassis 003, which would become the first production/customer DGF racecar.

Fickling and the new Eagle would make their debut at the Memorial Day weekend Riverside National event, where Fickling shocked everyone (including his teammate) by putting 003 on the pole, while Loring could do no better than 14th on the grid. In the race, Fickling comfortably led up to the halfway mark, until an overly optimistic pass attempt by the car in 2nd place, forced him off track. Fickling was able to recover and finish 4th, with Loring right behind him.

At Laguna Seca in June, the roles reversed as Fickling had the tough weekend and Loring took the pole and an eventual 2nd-place finish. Next up was a return to Riverside, where Fickling finished in the top five and Loring retired. This set the stage for the last race before the Runoffs, at Phoenix.

The weekend of September 10 found the Eagle duo at the height of their powers. Fickling put 003 on the pole by a full second over Loring in 2nd and established a new track record in the process. When the green flag dropped, Fickling took the lead, with Loring right behind. Fickling maintained that lead until about half distance when he came to a turn where sand had been thrown out on it. With no hazard flags waving, Fickling shot into the turn and immediately started spinning. When he came to rest, he was in the middle of the track facing oncoming traffic. Loring managed to miss him, as did the 3rd-place car, but the 4th-placed racer wasn’t so lucky. The oncoming car, sheared down into the side of Fickling, launching the opposing car into a horrifying flip and the impact badly injuring Fickling. Loring went on to win, while Fickling had badly damaged both his car and his body!

1978 Runoffs

With a little over a month until the Runoffs, Fickling began rebuilding his car while hobbling around on crutches. While still not 100 percent physically, he was able to get 003 back together and out to Road Atlanta for the Runoffs. Loring, on the other hand, had a different kind of struggle. While he and Fickling had shown the Eagle’s race-winning potential, AAR was not being flooded with orders. Likely due to a combination of its relatively high cost and the consistent bad rap being given the Eagle by its manufacturing competitors, the rank and file racers were not embracing it like Gurney had originally hoped they would. Added to this, the limited amount of sponsorship given to AAR for the program from ARCO petroleum had dried up, and on the Indycar side of AAR’s program, Goodyear was cutting back its significant financial support. Loring recalled the troubling situation, “We had to steal the car to get it to the Runoffs. The program was pretty much over. We hadn’t been selling cars, the cars weren’t working well, we’d lost a lot of money from ARCO, which wasn’t going to come back the next year for the Indycar, Goodyear had cut back its money a lot and the cars weren’t selling, so for all intents and purposes, the program was over. I said to Dan, ‘I’m going to win the Runoffs with this thing, I’ve been working on this for two years,’ and he says ‘Well, we’re not paying for it, we can’t afford to do it.’ So my engine builder, Charlie Williams in Kansas City, sent me out a trailer, and we took the car to Kansas where I prepped it, and then Kendall Noah, who owned Kansas City Metalcraft—you’ll see that name on the nose—paid for the hotels and all the expenses to get us there.”

Despite all the hardship for both Fickling and Loring, the Eagle duo did make it to the October 29 running of the Runoffs at Road Atlanta, though with decidedly different results. In Fickling’s case, he was still struggling with the physical ramifications of his Phoenix accident, and at Road Atlanta now found himself wrestling with such extreme vertigo that he was nowhere near on the pace of the frontrunners. Loring, however, finally saw it all come together. After qualifying 3rd on the grid behind the two Van Diemens of Peter Kuhn and Tom Davey, Loring capitalized on the Eagle’s superior aerodynamics to slingshot the pair at the start and dive into the first turn in the lead. “I won that race in the first corner, because I got a really good start and I drafted by those two guys and then just before the brake zone for Turn 5, when they were tucked in behind me ready to follow me up the hill, I did a big breathe on the throttle, and they had to jump on the brakes,” recalled Loring. He added, “Then I got back to full throttle without losing too much momentum, where they had to start the thing up the hill. So I got to the top of the hill and said to myself, ‘If you do the rest of this lap perfectly you can maybe break away,’ and about halfway down the back straight, I peeked up over the windscreen and they were side-by-side four or five car lengths back and when they kept fighting themselves, I just drove away.”

Not only would Loring go on to win, but he would do so by the largest margin of victory in SCCA history.

Killing a Champion

Ironically, by the time Loring won the SCCA National title, the Eagle DGF program was already dead and gone. Gurney summed it up, “What we didn’t understand was that it was an unwelcome situation as there was already a bunch of warring parties involved where each had hammered out a domain and didn’t want anybody coming in to upset it. They put out the word that we were a factory, and therefore the bad guys. So, with our little pickup truck and open trailer, we took a lot of abuse. So it was, I don’t know, it was more of an introduction to reality than expected.” In total, 12 chassis were built, the two initial prototypes for David Loring, followed by 10 customer cars, of which Bill Fickling’s was the first.

After the Runoffs, Fickling sold Chassis 003 and it slowly disappeared into the bowels of SCCA club racing. At some point in its future, 003 was converted to a C Sports Racer, with its frame heavily modified. By 2007, Indycar team owner Tom Figge had purchased the car with the idea of restoring it back to its original configuration for a racing museum he was building. While he went so far as to have restorer Fernando Bobedas fabricate a new chassis from 4130 steel tubing, the project stalled when the financial markets collapsed in 2008. In November of 2011, the car’s original owner, Bill Fickling, acquired the project and spent the next two years meticulously restoring the Eagle back to its original 1978 configuration and livery.

Driving the DGF

My test drive of Fickling’s Eagle (003) was something of a double homecoming. First off, this was very comfortable ground for me as I raced a Lotus Formula Ford for many years and absolutely loved the precision handling and total ease of maintenance. But not only was I going to get to drive a type of formula car that I have a lot of experience in, but I was going to do so at the track where I have probably logged the most laps, Willow Springs.

In many ways Willow Springs, in Southern California’s high desert, was the ideal place to test the Eagle. The car did its first testing here and in fact, the DGF was really designed for this circuit—long and fast—a place were its narrow track and slippery aerodynamics would yield the most advantage.

Strapping into the DGF was like putting on a favorite pair of slippers or moccasins—it just seemed to conform to my body in a tight, well-broken-in sort of way. As with all Formula Fords, the cockpit is the epitome of simplicity—simple, small steering wheel, a central tach, two small ancillary gauges, an ignition switch, starter push and fire system button. The only other dominating feature is the large, turned aluminum gear shifter, which falls perfectly to your right hand…ah, home!

With the ignition on and the Hewland in neutral, I crack the throttle and give the starter a jab, resulting in the crossflow Kent engine coming to life with an earnest, fast idle that lacks the “crackle” of a purpose-built race engine, yet still manages to communicate that there’s something serious behind your helmet. Dipping the clutch, I forcefully “graunch” the Hewland into first gear, squeeze the throttle while releasing the clutch and the DGF politely makes its way out into the Willow Springs pit lane.

The vast majority of the time, when I do these test drives, it’s in an unfamiliar car, at an unfamiliar track, so it’s here that I usually relay how awkward it feels coming to grips with the car and track over the first few laps…but none of that today. To be perfectly honest, by the time I got to the entrance to Turn 1, I was already completely at home and starting to get on it.

Accelerating out of Turn 1, in second gear, I set up for Turn 2 wondering if it has changed in the 10 years since I last raced here. Shifting up to third gear, I set the Eagle up to enter Turn 2 about a third of the way up from the inside edge of the track to try and take advantage of a groove that used to exist, lo those many years ago. As I hold a steady throttle through Two, feeling the lateral Gs starting to push the car outward, I’m met by a reassuring feeling—the groove is still there! The slight change in camber essentially holds the Eagle up and allows me to slingshot out of Two and down the short chute to the entrance of Turn 3. Turn 3 is the slowest turn on the course and is an almost 90-degree left-hander that also heads steeply uphill. Holding out the revs in third gear, I move to the very outside edge of the track and stand on the brakes as I toe-and-heel down two gears, all the way to first (Fickling has told me that first gear is so tall it’s good for 90 mph!). Pitching the Eagle down into the apex of Three, I get hard on the accelerator as the Eagle drifts to the right and launches up the hill. It’s here where I start to experience the unique handling characteristics of the DGF compared to other FFs. Due to the car’s narrow track and extremely stiff suspension, it feels more “go-kart-like” than any other FF I’ve driven. You can easily sense and feel the lateral movement of the car sliding, but without any real sense of side-to-side weight transfer or body roll, the car just starts to slide like it is carved out of a single piece of material.

Accelerating up the hill, I double apex Turn 4 (the crest of the hill) and get back hard on the throttle to try and maximize the short, downhill chute to the most critical turn on the course Turn 5. But it’s here where the Eagle almost catches me out!

Because the suspension is so stiff and the car is so narrow, the combination of turning right, getting hard on the gas and transitioning downhill—all at the same time—causes the notoriously tail-happy Eagle to break away. While I again didn’t have any sense of any weight transfer, the minute I got hard on the gas, I felt the rear-end start to come around. Trying desperately to resist that primal urge to back completely out of the throttle (guaranteed disaster!), I pull back to about half throttle as I saw the steering wheel left, then right in a lurid tank-slapper, before getting the Eagle back under control…whew! I know, somewhere in the pit lane right now, Fickling is wiping beads of sweat off his brow…

As mentioned above, Turn 5 is critical because the exit speed you carry will make all the difference as you navigate the rest of the track, all the way back to Turn 1. This starts the fastest two-thirds of the course. Racing downhill from my drifting demonstration, I downshift to second gear, turn down into the apex and squeeze the throttle back to full by the time I hit the apex, this launches the Eagle out of the left turn and up and over a short, blind brow at the apex of Turn 5. This is always a “Hail Mary” moment because you are cresting a blind brow, while turning into the apex, on full throttle and upshifting as you crest! Done right, you fly down the back straight. Done wrong….let’s not talk about that.

The last half of the track is all a combination of confidence in your car and pure testicular fortitude. After snatching top gear on the back straight, you set yourself up on the outside for the turn-in at Eight. In a Formula Ford, this turn is essentially taken flat, cutting down toward the apron and then letting the car run far outside to set up for the decreasing radius at Nine. However, while you can know this in your mind, as you hurtle into it at what seems like an impossible speed, there is always that brief crisis of conscience, “This isn’t going to work!” While I did in fact take a slight “confidence lift” going into Eight, I was surprised by how stable and confidence-inspiring the Eagle felt here, despite our brief moment at the top of the hill, moments before!

Bombing into the outside of Turn 9 at what seems like Mach speed, I briefly lift, wait a beat (turning in early at Nine has horrible consequences!) downshift to third and then turn the Eagle’s nose down into the right-hand apex as I squeeze her back up to full throttle and drift to the outside on the exit. From here it’s a single upshift and a full throttle bomb down the front straight with plenty of time to look at the gauges and contemplate the next lap.

As the laps went on, I continued to be amazed by the Eagle’s precision and poise, but also became cognizant of how difficult the car might have been for many competitors to drive right on the edge. As Loring later commented, “In all honesty I think the problem with the car was we had made it too much to my liking. It was probably too stiff for most people. It had huge (anti-roll) bars for a Formula Ford, it probably didn’t tell the average driver too much about what was happening, but if you could drive the car, it was wicked quick.”

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Heliarc-welded, steel spaceframe

Wheelbase: 95 inches

Track: (F) 54 inches, (R) 52 inches

Width: 62 inches

Weight: 935 pounds

Engine: Ford Kent, inline, 4-cylinder

Displacement: 1600-cc

Suspension: (F) Unequal length A-arms, inboard coilovers, with adjustable anti-roll bar. (R) Upper lateral link, inverted A-arm lower link, radius rods, outboard coilovers, with anti-roll bar.

Transmission: Hewland Mk9, 5-speed.

Brakes: 9.5-inch Lockheed rotors and calipers.

Resources / Acknowledgements

Zimmermann, John, Dan Gurney’s Eagle Racing Cars, Bull Publishing, 2007.

Nickless, Steve, The Anatomy & Development of the Formula Ford Race Car, Motorbooks, 1993.

Lyons, Pete, “Hatching an Eaglet” Parts 1-4, Formula Magazine, 1978.

Kirby, Gordon, “The Way It Is: Appreciating the life of an old friend” gordonkirby.com, 2012.

The author would like to thank Bill Fickling for both his endless patience and support in seeing this article come to fruition. Additionally, the author is deeply indebted to the assistance and forethought of John Zimmermann, who fortuitously for the author, saved and shared all of the transcripts of his conversations with David Loring, who passed away in 2012.