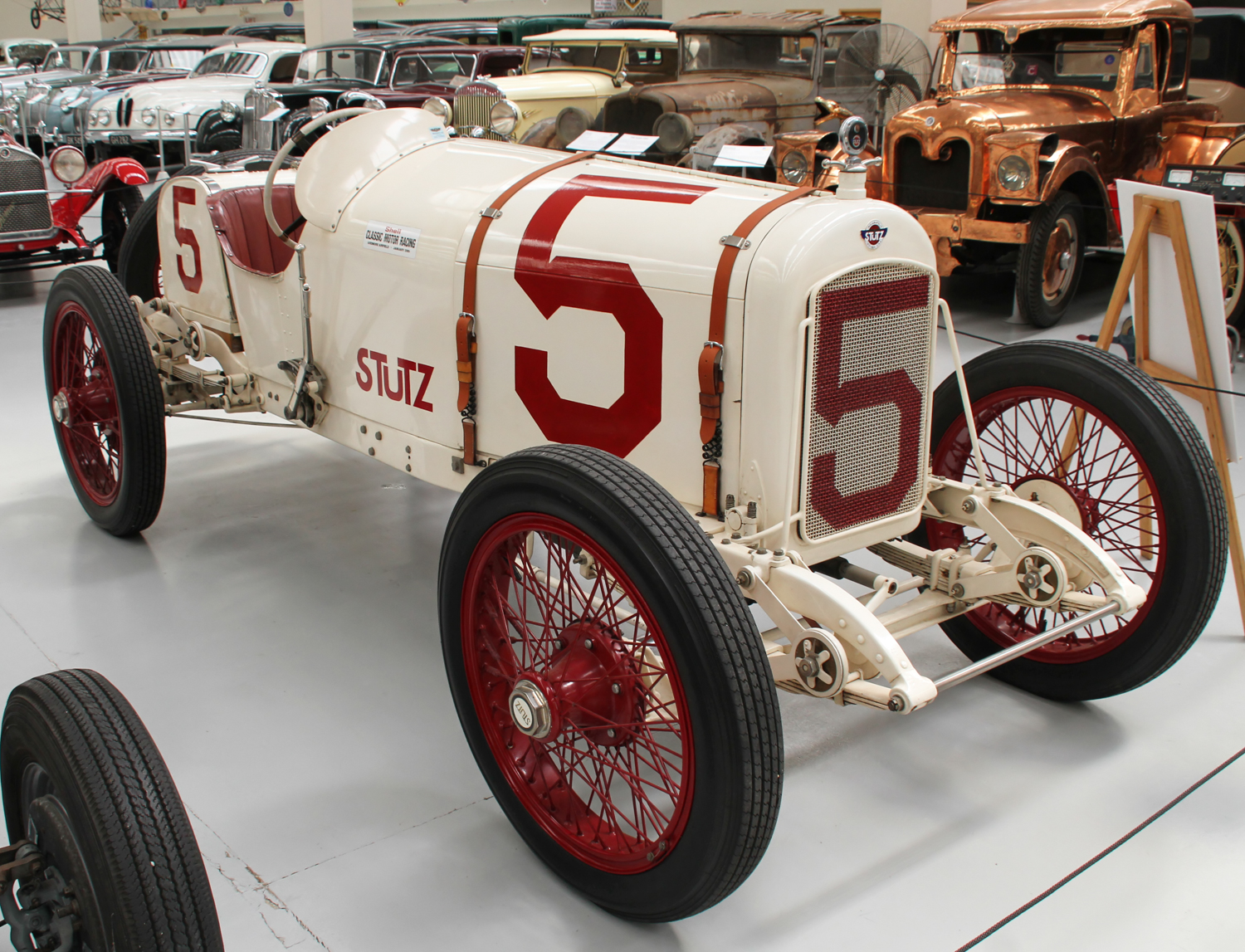

Its Spartan dash has a tachometer, oil pressure gauge and fuel pressure gauge. There is no speedometer. There is also a pull out knob, at the top of the panel, to pump air into the gas tank because you have to pressurize it to start the car. Once the engine is running, a vacuum tank takes over and keeps the fuel flowing. The only temperature gauge is in the radiator cap.

The clutch and brake pedals are in their usual places, but the throttle pedal is between them and sits a bit lower, so the clutch and brake pedals can help hold the driver’s foot in place. That way the driver can keep the pedal to the metal even on rough roads, and there were plenty of them in 1915. The gearshift lever is mounted outside the cockpit on the driver’s right, as is the parking brake. A spark lever and a throttle quadrant are on the steering wheel.

Little Al feels around to assure himself of where things are, adjusts the rear view mirror, fiddles with the spark, and then is off in a sudden lurch thanks to the car’s leather-faced, all-or-nothing, cone clutch. He is doing a celebrity run at an event called the Leadfoot Festival, near the seaside town of Hahai, on the Coromandel Peninsula in New Zealand, and taking the car up legendary Kiwi rally driver Rod Millen’s winding, curving, and at points steep, mile-long driveway.

For those of you who were not born yet, or were otherwise occupied during Unser’s racing career, he won the centerseat Can-Am Championship in 1982, the IROC Race of Champions in 1986 and ’88, and then took the Indianapolis 500 twice; first in 1992 and then in 1994. He also triumphed in the CART Series’ Long Beach Grand Prix an astounding six times, and took the CART Indy car world championship twice for good measure.

But driving the Stutz was a handful, according to Little Al, as it would be for anybody not familiar with the cars of a century ago. “You only have rear brakes, and it steers like a truck but it goes great for how old it is,” he said. The two-wheel, rear only mechanical brakes on the Stutz were business as usual in 1915, and indeed had an edge on many contemporary cars that only had one brake mounted on the driveshaft. Front wheel brakes came later, as did hydraulic brakes.

I did not drive Little Al’s Stutz, but I can tell you from having piloted a later Bearcat, the street version of the car, that you are out there in a tiny seat with no seatbelt, and though you may only be doing 60 or 70 miles and hour you feel like you are setting the land speed record. As Stirling Moss once said, it is not speed, but the perception of speed that is thrilling. Take-off speed for a Boeing 747 is 160 miles per hour but you barely notice it. However, 60 miles an hour in an open antique racer seems like warp nine, to use an old Star Trek term.

Another interesting and unique thing about our 1915 Stutz Indy car is that it has a massive transaxle in the rear. This transmission and differential combination—designed by Harry Stutz himself—is all one unit, which makes for a very sturdy reliable drive train, but it has one major shortcoming when it comes to racing.

Roads were generally terrible back then, and even Indy was paved with greasy uneven bricks, so the transaxle had to be sturdy— and as a result it was also heavy. And that cost Stutz in the 500 because it caused unusually high tire wear, which resulted in too many pit stops, and that cost the White Squadron (as the Stutz team was called) the 1915 outright victory.

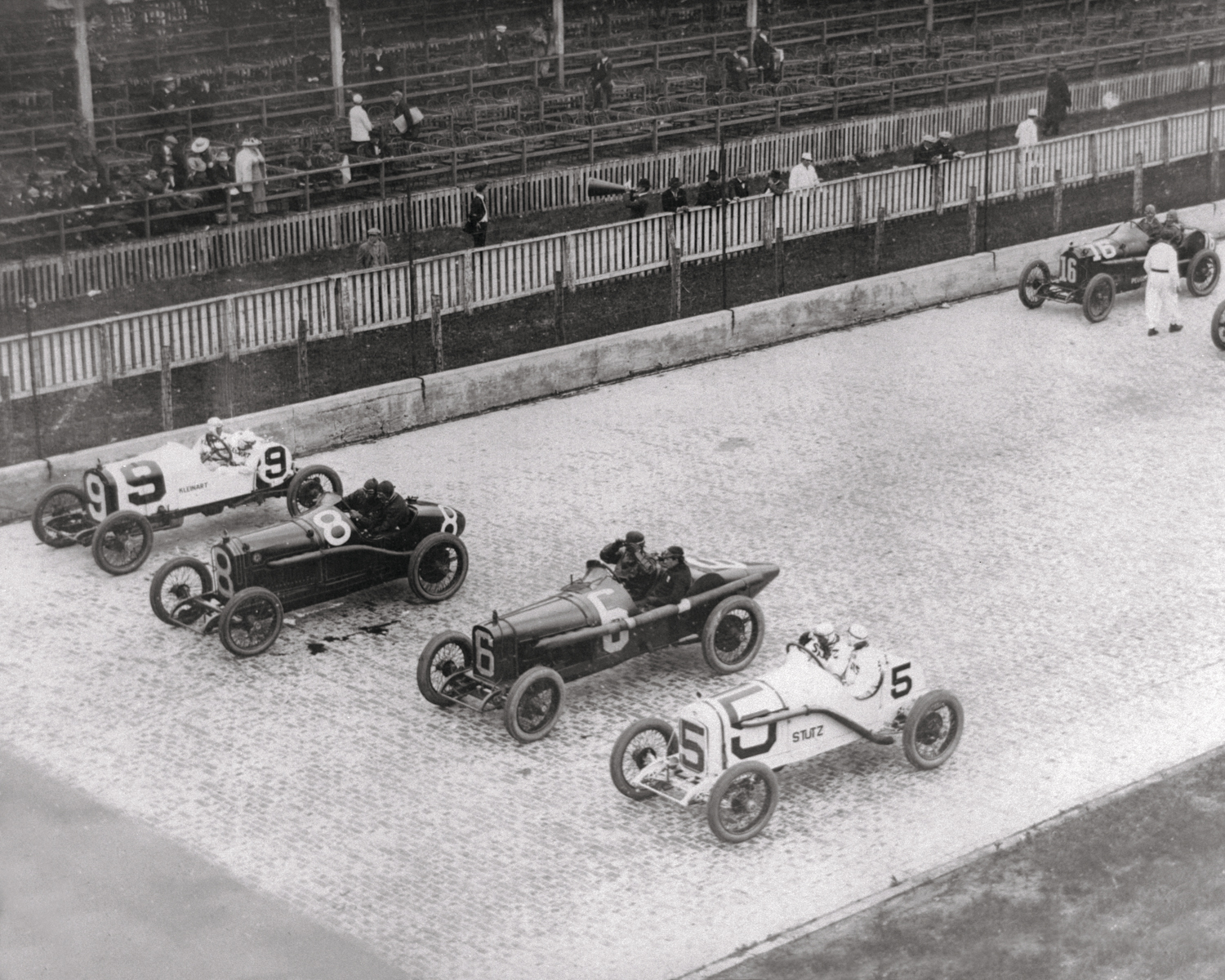

Harry Stutz, after great previous success with his racecars and Bearcat sports cars, entered three cars in the 1915 Indianapolis 500 race. He knew exactly what he was doing at the time too, because his strategy was to make sure that his first two cars qualified at under 97 miles an hour. Then his third car, piloted by Howdy Wilcox, came out late and qualified at 98.9 mph to take the pole.

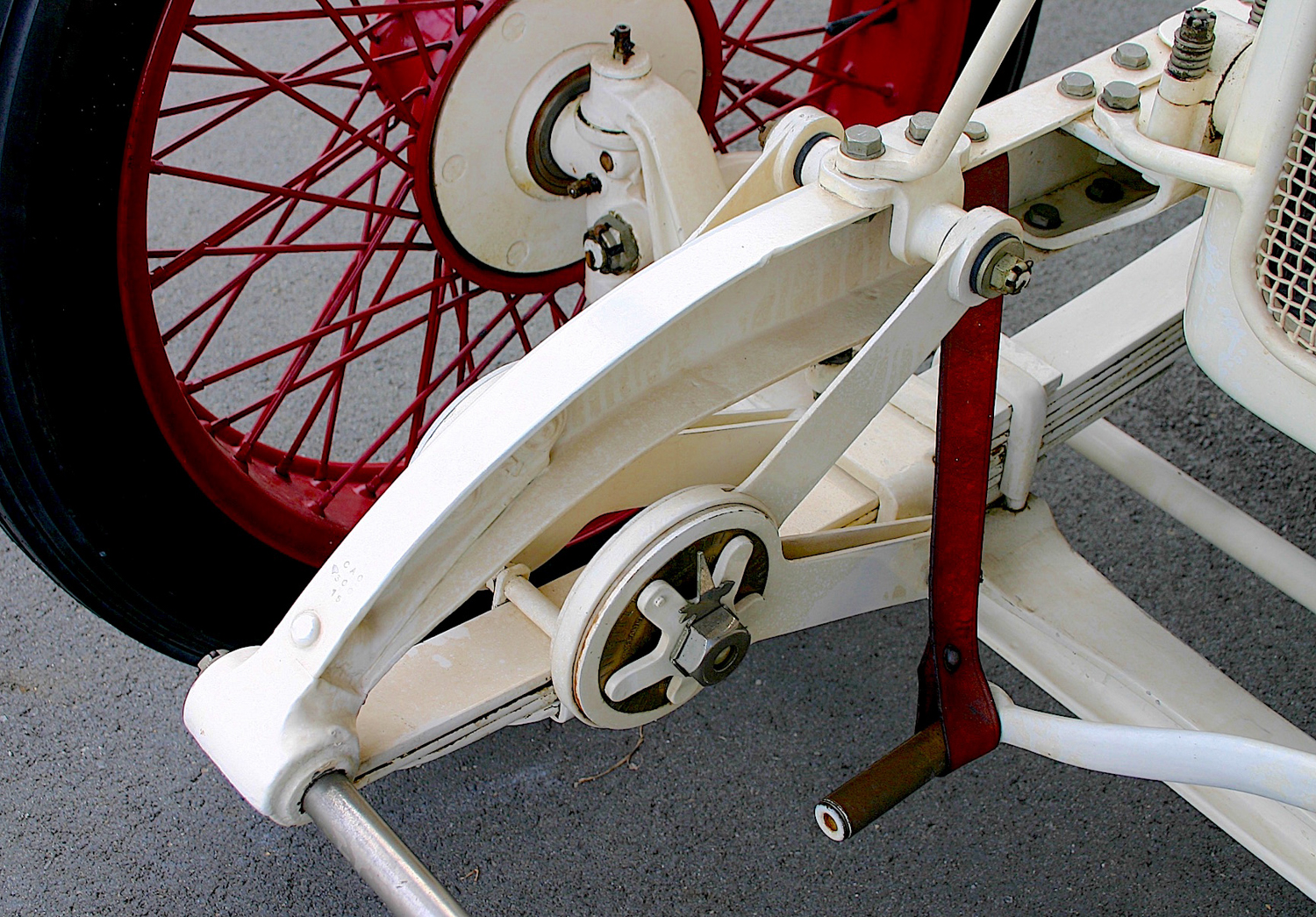

An innovation that helped the Stutz was its underslung chassis, pioneered by Stutz in 1905. This configuration transferred the weight of the chassis from the top of the axles and springs to being slung below them. That was accomplished by mounting the springs on the outside of the chassis with shackles that put the spring eyes above the frame. This lowered the car’s center of gravity, and helped in cornering immeasurably.

The night before qualifying, Wilcox noticed that Stutz was wearing a diamond stickpin that he much admired, so he talked Stutz into agreeing to a wager that if he took the pole, Stutz would give him the stickpin. And if he failed, Wilcox would buy Stutz a steak dinner. Wilcox put his foot down the next day and took the pole at 98.8 miles per hour and acquired the stickpin, as per the bargain.

Interestingly, 1915 was the first year at the Indianapolis 500 that the starting order was determined by the qualifying speed of the entry. Before that you had to qualify, but the starting order was determined by pulling numbers out of a hat no matter how fast you went. That was largely because, in the beginning, Indy was as much an endurance race as anything else, and many entrants were not able to finish the race. Many manufacturers of automobiles of the era recommended an engine tear down and overhaul every 500 miles.

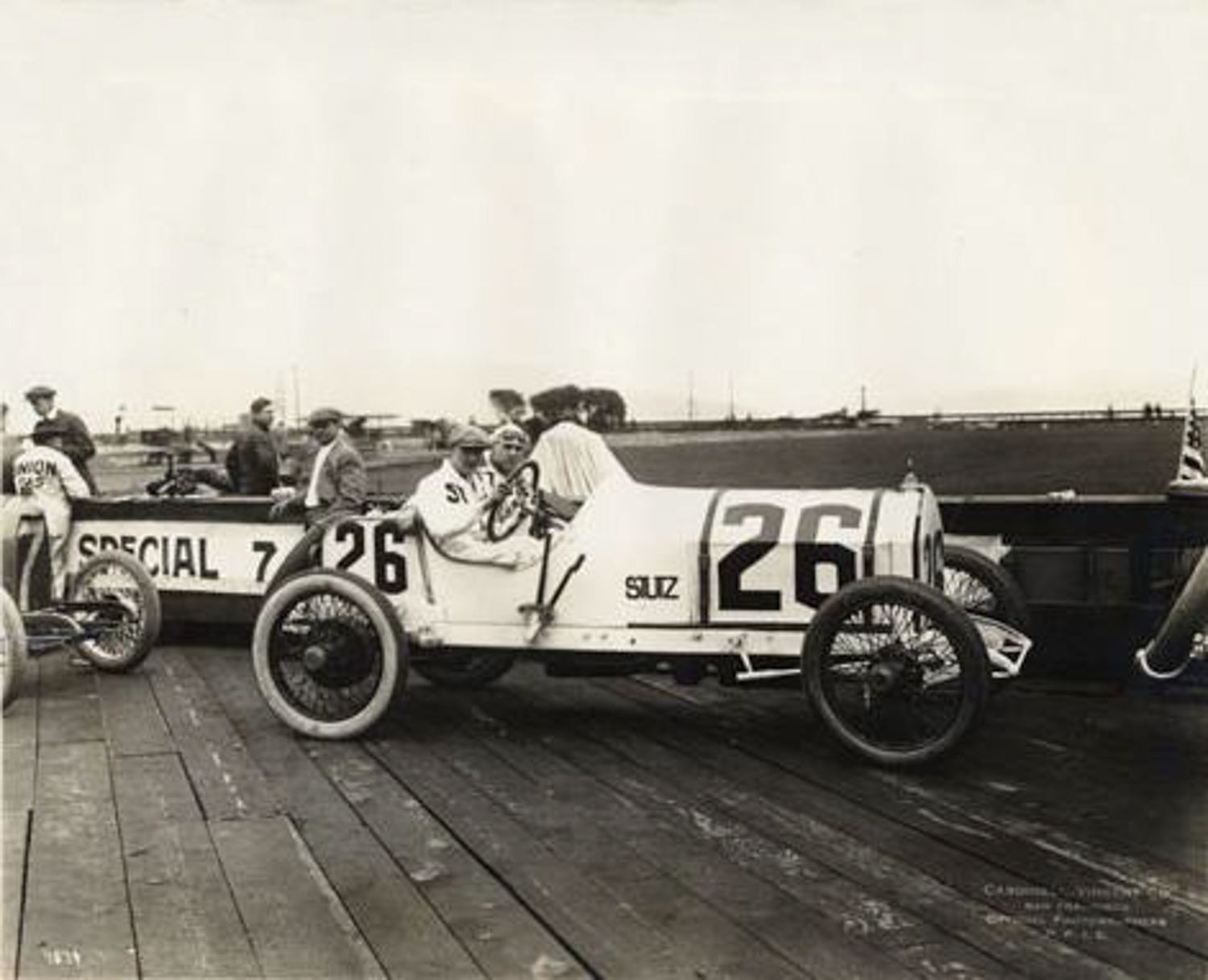

Also of note that year was the fact that the Indy 500 was delayed due to rain. Postponed from May 29 to May 31, the town of Indianapolis was quickly swelled by an additional 100,000 extra visitors that came in, in anticipation of the delayed race. Housing and food became scarce and there was concern of riots if the crowds were not distracted. Speedway owner Carl Fischer quickly came up with a plan, which was for Barney Oldfield to climb into Gil Anderson’s #5 Stutz on Sunday the 30th and race DeLloyd Thompson in a biplane!

Once the 500 was finally underway, on Monday May 31st, unfortunately, Wilcox’s leading Stutz broke a valve spring during the race, at which point the second Stutz of Gil Anderson took the lead. But in the end, excessive tire wear caused Anderson’s, and teammate Earl Cooper’s, Stutz entries to require repeated pit stops, costing Stutz the over all win. Ralph DePalma driving a Mercedes, took the checkered flag while Anderson and and Cooper finished third and fourth respectively.

But today, more than 100 years later at New Zealand’s Leadfoot Festival, Anderson’s old Stutz showed the crowd what she could do, and though she was no longer competitive—what with the modern BMWs, Peugeots, and Porsches—she was still astoundingly swift heading up the hill with Unser at the helm. Watching Little Al do what he does best in an antique racecar was a thrill, and a death defying one at that.

Pushing an antique racer with no roll bar, and no seatbelt because the driver was expected to jump out in the event of a crash to avoid being crushed or burned in a fire, along with the car’s high center of gravity, two wheel rudimentary brakes and large spindly wheels that would be stressed to the max through twists and turns on the winding road course, made the hair stand up on the back of my neck.

Those lacy delicate wheels could easily fail (and often did) under heavy side loads in the corners. And those narrow tires only presented a minuscule footprint for establishing control of the heavy 120-inch wheelbase machine. The Stutz’s primitive friction shock absorbers were treacherous too. They were simply steel disks with leather between them, and a bolt holding them together that you tightened to get a firmer ride. But dust and moisture could change that equation radically on the track.

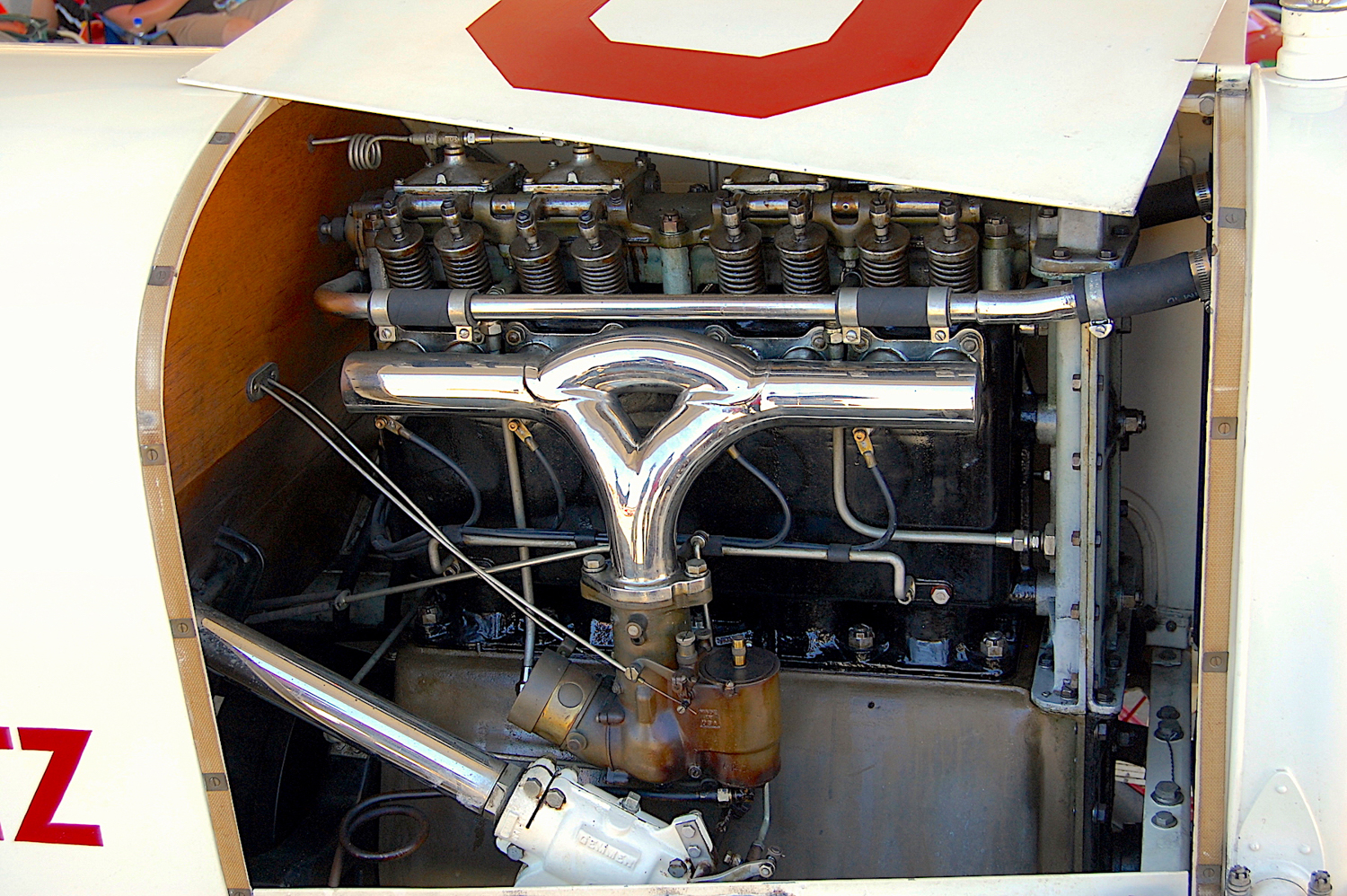

The Stutz’s 296.8-cubic-inch, four-cylinder Wisconsin engine, has a bore of 3 3/16” and an exceptionally long stroke of 6 ½” so it makes massive bottom end torque. But with its flat profile crankshaft and no counter balance weights, it makes the engine more like a twin two-cylinder rather than a conventional four. All that plus heavy steel pistons and rods limited the engine to a red line of not much more than 2,000 rpm.

However, on the plus side, the old Wisconsin had three massive ball bearings as main bearings, and a desmodromic, gear-driven overhead camshaft with four 1 ½” valves per cylinder in a cross-flow head that was cutting edge technology in 1915. Wisconsin supplied all of Stutz’s engines at the time, and Harry’s cars were assembled largely from components from other manufacturers.

There is no doubt that the Wisconsin power plant was heavily influenced— as were most of the racing engines of the time— by the brilliant Peugeot and Delage engines that ran at Indy in 1912. Indeed, the Peugeot four-cylinder, dual overhead cam, hemi head, four valve per cylinder, cross flow engine paved the way for the racing motors, including Meyer Drake Offenhauser engines that dominated American auto racing for the next 50 years.

Harry Stutz

The legendary Stutz racers and Bearcat sports cars (and yes, there is such a creature, but it is neither a bear nor a cat, but related to the weasel) were the brainchild of Harry Clayton Stutz. He was born in Ohio in 1876, and he discovered early on that he had a knack for fixing farm machinery, so he trained as a machinist and later found work with local sewing machine and cash register companies.

However, the new horseless carriages intrigued him, and he built his first car in 1897 after experimenting with internal combustion engines as a sideline. After that he formed the Stutz Manufacturing Company to build his engines, and then sold the business in 1902 to Lindsay Automobile Parts Company of Indianapolis, where he had moved to be with the company. Later, he founded the Central Motor Car Company, before moving on to Schebler Carburetor in 1904.

Clem and Mary C Lange – Huntingburg, IN

And then, in 1905, he designed an automobile for the American Motor Car Company and, in 1907, he became chief engineer and manager of the Marion Motor Car Company. While at Marion he became one of the company’s race drivers and learned a bit about that dark art. He then formed Stutz Auto Parts Company in 1910 to manufacture his innovative transaxle that he used in his Indy cars and Bearcats.

Around this time also, the founders of the Indianapolis racetrack took an interest in Stutz and he helped design a car for them. And with the advent of the first 500-mile race, he built his own entry in just five weeks that he called the Bear Cat. His car finished 11th, stopping only for tires and fuel, which was impressive when you consider that in those days many entries didn’t finish at all. That was when Stutz adopted the slogan: “Stutz— the car that made good in a day.”

The Indianapolis 500— and racing in general—was pretty basic back then. For one thing, the pits were just that. Open pits in the ground over which you drove your car to work on it. Hydraulic lifts came much later. Also, ride-along mechanics were common, and later even required, into the 1930s. The ride-along mechanic was expected to fix the car and change tires beside the track if necessary, hence the spare tire on the rear. It is hard to say which took more guts, driving or being the mechanic.

Thanks to this initial success, Stutz was able to combine his Stutz Auto Parts business with the Ideal Motor Car Company, in Indiana, and in 1913 he changed the company’s name to the Stutz Motor Car Company and began producing his legendary Bearcat for the streets, which was essentially the Stutz racecar with fenders and lights. The Bearcat was the Shelby Cobra of its era, and appealed to the young, well-to-do, hip flask toting, raccoon-coat-wearing playboys of the day.

Though the White Squadron was a great success, Stutz and the Stutz Motor Company retired from racing in October of 1915, and Harry Stutz himself left the company in July of 1919 along with his partner Henry Campbell, to establish the H.C.S. Motor Car and Stutz Fire Apparatus Company.

The Stutz Motor Car Company went on to build several more speed record setting cars, however, the company decided to concentrate on the luxury car market in the boom times of the roaring twenties, building some of the most beautiful and innovative cars of the era. The Weyman-bodied touring cars, circa 1930, were especially elegant, and were designed by Gordon Buehrig of Auburn Cord Duesenberg fame.

Stutz was also quite innovative, and was among the first to offer hydraulic brakes, though the system used water instead of hydraulic fluid. And the Stutz Motor Company was also first to use safety glass in their closed cars. The initial Stutz cars with safety glass had windows with wire embedded in them to keep them from shattering, but the company went on later to adapt the laminated safety glass we have today.

Safety glass was an important breakthrough – no pun intended – because up until that time most cars were open, with Eisenglass plastic side curtains, for safety reasons. Closed cars with plate glass windshields and side windows made drivers and passengers vulnerable to terrible injuries in accidents.

But in the end, as well engineered and beautiful as Stutz automobiles were during the twenties and early thirties, the company went the way of other small independent luxury car makers such as Marmon, Duesenberg, Pierce and Du Pont in 1935. As with other marques catering exclusively to the carriage trade, Stutz could not survive in the much diminished depression era market. Packard made it for a time by expanding into mid-priced cars built on an assembly line, and Cadillac Chrysler and Lincoln survived thanks to Big-3 backing.

After its ill-fated effort, in 1915, the White Squadron Stutz racer we had the honor of seeing at the Leadfoot went on to win the Astor Cup race in 1919, which was 350 miles, and it did it at an average speed of 102.6 miles an hour. It then went on to take second place in the 1919 Indianapolis 500 in the hands of Eddie Hearne, though it was now badged as a Durant.

After that, Anderson’’s Stutz racer was brought over to New Zealand in 1923 and competed successfully in many events in that country, including domination of the Muriwai Beach Races. And it also won the New Zealand Cup events in 1926, ’27 and ’28 driven by Kiwi racer Bob Wilson.

After that, the car was dismantled and its engine was used in a speedboat with its chassis becoming a tractor, albeit with a different engine. It wasn’t until many years later, in the late 1950s, that the chassis and engine were reunited and the famous racer restored by the Southward Car Museum, in Paraparaumu, near Wellington, the Capitol of New Zealand, who graciously permitted the car to participate in the Leadfoot Festival.

Al Unser Junior made exciting runs with the car several times over the Festival weekend, and had a big smile on his face most of the time. He had been invited as a celebrity race driver, and after the two-day event he told Rod Millen: “It’s been an absolute treat to drive the Stutz. I’ve been going up and down the driveway waving to the fans and they were all waving back.”

It was a treat for me to be able to say hello to Little Al too, and to be taken back in time to a day when auto racing was daring and dangerous, with innovation happening at an exponential rate. And it was great to see just how well a racecar built over 100 years ago could actually do in a modern event.

If you can get away during our American winter next year, I highly recommend you come to New Zealand, where it will be summer, and enjoy this three-day event. It includes entries from every era of motorsport including the latest rally cars and drivers, and you can watch from a number of great vantage points. It is in a beautiful setting much like California’s Big Sur, and accommodations are plentiful.

In fact, New Zealand is a great place to visit for car buffs in general and has a number of major events every year with cars from all over the world. There is the Bruce Mclaren Heritage Centre at the Hampton Downs raceway near Auckland, which houses many of his cars, trophies and awards, and there is a lot of good racing at the track too, with vintage as well as contemporary cars.

And then there is the Southward Car Museum that provided the Stutz, that has a collection of over 400 vehicles, including the late Mickey Cohen’s Cadillac with its inch thick bulletproof glass, and of course, our legendary Stutz Indy car, available for closer inspection. They are open most days, and are just outside Wellington on the North Island.