1975 Eagle 755 F5000

In 1967, the SCCA began a fledgling “professional” category for open-wheel formula cars known as Formula A. The idea was to provide a series of five races, open to F3, F2 and 3-liter F1 cars, with each race having its own $5,000 purse. Though the turnout was a bit spotty the first year, the SCCA came to believe that by allowing competitors to use the more easily accessible and lower cost, 5-liter Chevy V8 engine the change might add enough speed and excitement for the series to really take off and stand as an American version of Formula 1. Thus, starting with the 1968 season, Formula 5000 was born.

In those first years of Formula 5000, if you wanted to be competitive you needed to be racing one of Dan Gurney’s F5000 Eagles. These early Mk V Eagles, which were penciled by the AAR design team lead by Tony Southgate, were a subtle variation on All-American Racers’ USAC Indy cars, but were effective enough in F5000 form to carry Lou Sell to the inaugural championship in 1968 and Tony Adamowicz to the championship in 1969. However, with the start of the ’70s, AAR’s F5000 fortunes shifted as first the McLaren and then the Lola chassis began their respective rises to dominance.

By 1972, F5000’s stature (and prize money) had grown to such an impressive extent that Dan Gurney decided that it was time to develop an all-new Eagle F5000 design. Interestingly, during this same period, the prevailing chassis rules package for both F5000 and F1 were so similar that Gurney and his team set out to design a cutting-edge car that would not only be competitive in F5000, but that could also be run in F1 as well.

Photo: Casey Annis

So, near the end of 1972, AAR chief designer Roman Slobodynskyj and his assistant Gary Wheeler sat down to design the Eagle that was hoped to both recapture AAR’s previous F5000 glory and possibly reintroduce the Eagle name to Formula One.

An Eagle is Born

Slobodynskyj’s new F5000, dubbed the 73A, first turned a wheel in anger in the summer of 1973. The new Eagle featured a rocker-arm front suspension, in-board front brakes, a very low center-of-gravity and benefitted from much of the aerodynamic knowledge garnered from AAR’s highly successful USAC Indy car program. However, right from the beginning, the 73A – or Jorgensen Eagle as it was known due to AAR’s sponsorship from Southern California’s Jorgensen Steel Company – began to have problems. One of the first and most pressing problems was that the car was prone to overheat. When this was coupled with the already heat-sensitive, high horsepower engines being built by AAR engine guru John Miller, the result was a car that would often succumb to head cracking after 20-30 laps of hard running.

Testing of the new 73A went on into 1974, with a number of drivers putting the car through its paces including Sam Posey, Brett Lunger and AAR Indy car driver Bobby Unser. Eventually, design changes were made to try and minimize the overheating problems, but according to AAR designer Gary Wheeler, “The problems could never be fully overcome due to a miscalculation of the required radiator face area.” In fact, the Eagle’s tendency to over- heat would be a problem that would plague both the 73A and its successor the 755.

Photo: Casey Annis

As the start of the 1974 season loomed near, AAR completed the construction of four new 73A’s and chose as its driving team Brett Lunger, the wealthy DuPont family heir, and rising Super-Vee champion Elliott Forbes-Robinson.

Season of Discontent

Unfortunately, the 1974 F5000 season was stricken – before it even got started – by the oil embargo that was crippling the United States at the time. In an era of fuel shortages and long gas lines, the concept of sponsoring a race series that featured raucous V8-powered racecars guzzling high octane fuel no longer seemed like a good marketing move to series sponsor L&M cigarettes, and so they withdrew their substantial financial support. Ironically, USAC was struggling at the same time with their poorly supported road racing series as well. As a result, the powers that be from both series decided to combine forces for 1974 and run a joint road racing series that would allow both USAC Indy cars to compete in the seven race F5000 series and F5000 cars to com- pete in selected USAC oval races.

The 1974 USAC/SCCA F5000 Championship opened at Mid-Ohio on June 2nd with Lunger being the only Eagle to qualify (5th position) for the main event, though he was nearly three seconds a lap slower than the pole-sitting Lola T332 of Mario Andretti. However, despite this obvious speed disadvantage, Lunger was able to ultimately bring the Eagle home in 2nd place behind the Lola of Brian Redman, providing a solid debut performance for the new Eagle.

The next round at Mosport went much the same way with both Lunger and Forbes-Robinson qualifying mid-pack – about 4 seconds a lap off of pole time – but with Lunger again salvaging a podium finish with a somewhat distant 3rd place. While both of these results, on face value, appeared encouraging, the team had quickly come to the realization that the 73A was heavier and slower than the Lola T332. According to Slobodynskyj, “Unfortunately, I think it was a mistake to try and build a car that would accept both the 5-liter V8 and the Cosworth DFV. The drivers that drove the 73A really liked the way the car drove, but it was slow…or rather slower than the Lola T332; and ultimately, in retrospect, I think it was due to the fact that it was overweight.” While Wheeler (who would go on to become chief designer after Slobodynskyj left AAR in 1975) agrees that the 73A was a bit too heavy, however he also feels that much of the car’s lack of competitiveness stemmed from problems with the rear suspension geometry: “At the time, Dan was very insistent that the 73A have as low a center of gravity as possible. However, this posed a problem because by running the car so low to the ground, we ended up running out of suspension travel. This often resulted in the car bottoming out on the bump stops, which dramatically affected its handling capabilities. This geometry problem was most notice- able in slow speed turns where the Lola’s where able to get on the gas almost two car lengths before we could.”

As the season progressed the Eagle suffered a string of mechanical problems and accidents that resulted in the 73A not making it into the top 10 again until the last race of the season. However, by early summer Gurney and his team had already turned their attention to designing and building a replacement for the 73A that would hopefully debut before the end of the season. According to Slobodynskyj, “Our philosophy with the new car was to make it lighter and more simple.”

The 755

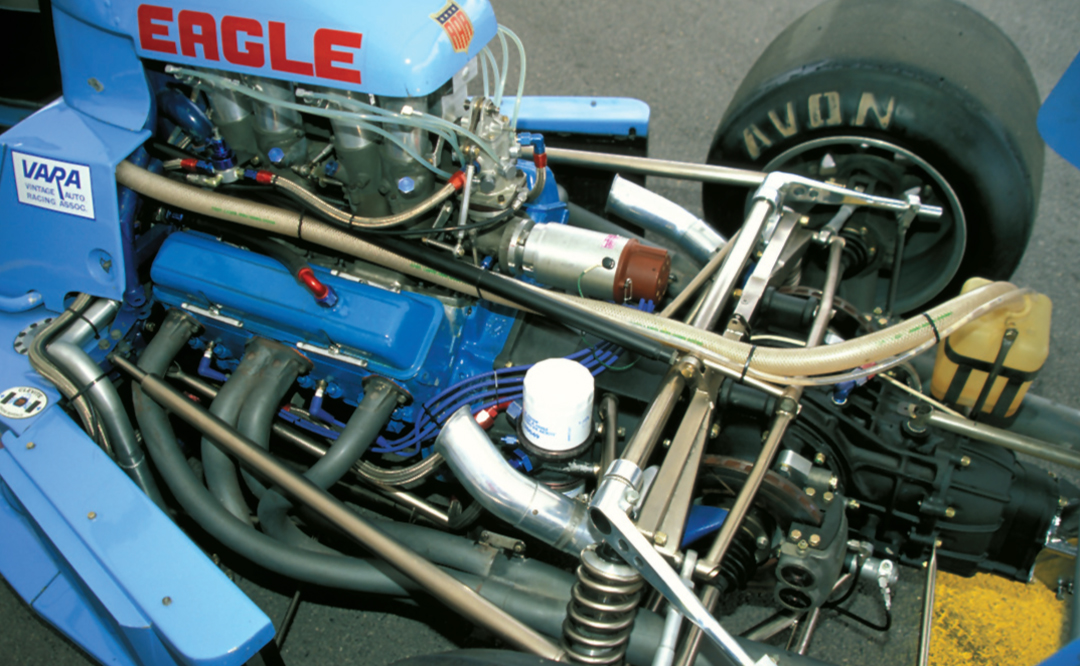

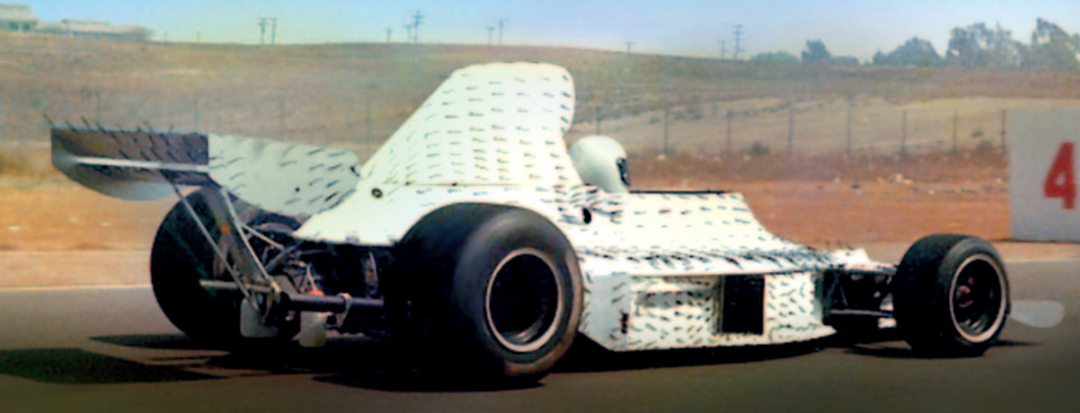

The new Eagle, dubbed the 755, did end up being a far more conventional design than its predecessor. The use of an aluminum monocoque tub was retained, but the rocker-arm suspension used on the 73A was replaced with fabricated A-arms and the heavy inboard front brakes were replaced with conventional outboard ones. At the back of the car, the new 755 still utilized one of John Miller’s 305-cu.in. Chevy small block V8s, inhaling gasoline through a Lucas mechanical fuel injection system. Power from this unit was fed through a Hewland DG-300 5-speed transaxle and put to the ground through a similar independent, parallel link rear suspension setup that had been used on the 73A. The overall styling of the 755 was also dramatically changed, incorporating more of a minimalist “arrow-like” appearance that featured a very low amount of frontal area. This new design provided significant weight savings since the tub now also served as much of the external bodywork – the only fiberglass body pieces being the nose, a small “conning tower” section wrapping around the driver and the air scoop mounted over the engine’s inlet trumpets. The net result of all these changes was that the new 755 was about 75-100 lbs. lighter than the 73A.

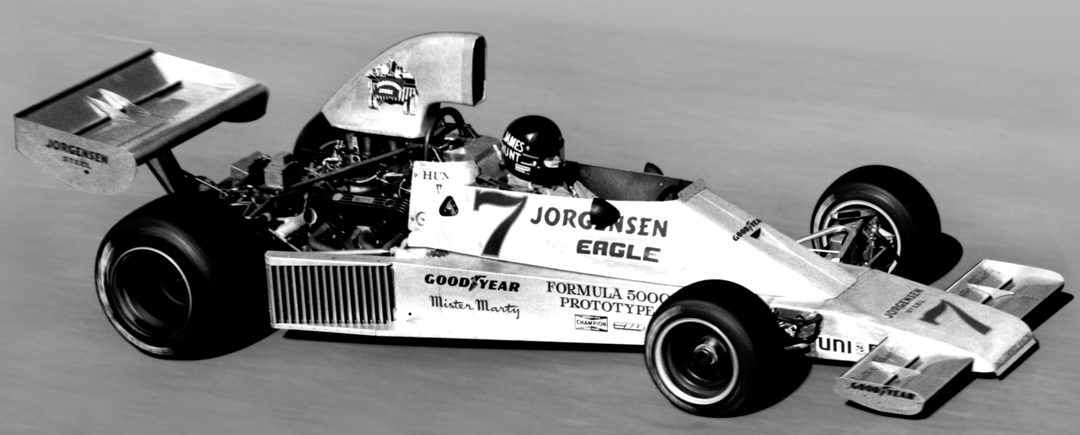

As the team had hoped, the new 755 was able to make its racing debut before the end of the 1974 season and, in fact, ran in the last two events at Laguna Seca and Riverside. For both of these races, Gurney was able to secure the services of rising Formula One star James Hunt to drive the new 755. At Monterey, Hunt immediately set the field on notice that there was a new Eagle in town when he qualified the 755 3rd on the grid behind series powerhouses Mario Andretti and Brian Redman. In the race, Hunt had a storming drive, finishing in 2nd place just 30 seconds behind winner Brian Redman and 20 seconds ahead of Andretti. For all intents and purposes, it appeared that the Eagle had landed.

The final race of the 1974 season was held at Riverside Raceway and was one of the events where the USAC Indy cars were invited to participate. Being AAR’s “home track” Gurney entered three cars for the season-ending event: Hunt in the new 755, Lunger in the 73A, and Bobby Unser driving a turbo Offy 73A Indy car. In qualifying, Unser qualified 2nd with Hunt start- ing 7th and Lunger 11th. At the start of the race, Unser got the jump on Andretti and led the first eight laps until his engine expired, while Hunt crashed the 755 into the Turn 9 wall on the 38th lap. This left Lunger in the 73A to soldier on to a 6th place finish while John Morton drove a privately-entered 73A to 7th place.

A New Beginning

For the 1975 F5000 season, AAR chose to concentrate on just a one car effort, so the 755 raced by Hunt at the end of ’74 under- went a few modifications in anticipation of AAR team driver, Bobby Unser, racing it for the ’75 season. These modifications included: a supplemental, nose-mounted radiator to help address the perennial cooling problems; the front anti-sway bar being relocated so it could be made larger; and a high-mounted, more streamlined air box, which it was hoped would improve the flow of air to the rear wing.

The first race of the ’75 season was held at Pocono on June 1, where things picked up much as they had left off – the Lola’s were quickest with Andretti, Al Unser and Brian Redman driving and the Eagle was 6th fastest still about 2 seconds a lap off the pace. In the race, Unser could do nothing to improve the situation and finished, as he started, in 6th place.

The next round was the tricky Canadian circuit at Mosport where Unser could qualify no better than 8th – some five seconds off of Mario Andretti’s pole time. Unfortunately, the situation got worse in the race when Unser went out on the 17th lap with a sus- pension failure. It was at this point that things momentarily unraveled for the AAR team. While the details are not well understood, Unser decided to abandon the Eagle F5000 effort after Mosport and concentrate on the USAC championship (of which he had just won that year’s Indy 500 in an Eagle). Some have attributed his departure to the relative uncompetitiveness of the new 755 while others suggest it was due to the fact that he had already signed a contract to race for Roger Penske in USAC. Whatever the reason, his untimely departure left the AAR team looking to find a suit- able replacement driver partway through the 1975 season.

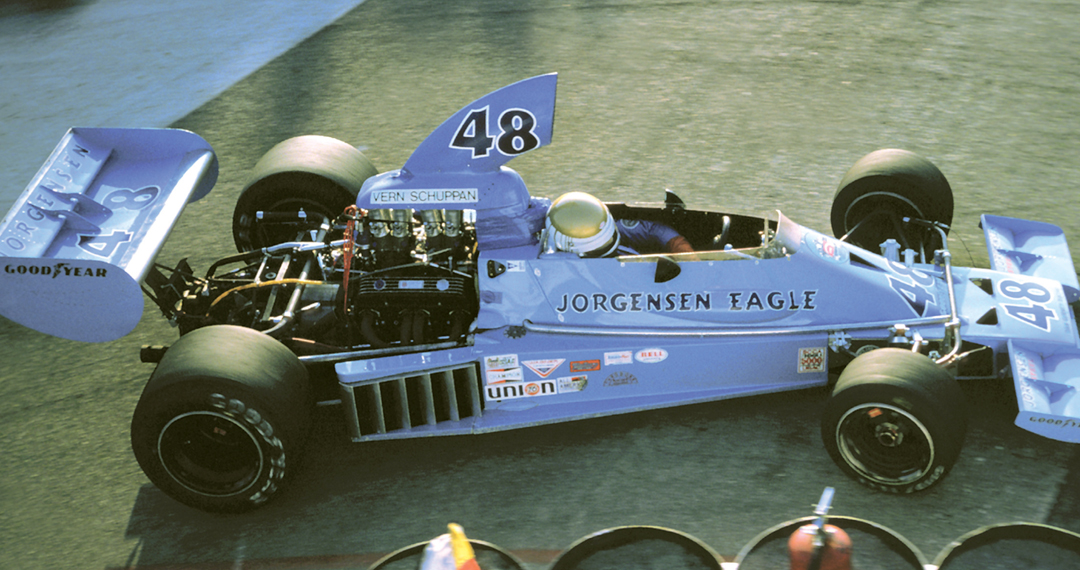

Unser’s eventual replacement came in the form of Australian Vern Schuppan, who had been designated Unser’s back-up driver at Pocono, when it momentarily appeared Unser would not be able to drive due to illness. Schuppan came with good credentials having already raced F5000 the previous year in a Lola and having also done stints in F1 with BRM and Ensign.

Schuppan made his AAR debut with the 755 Eagle at Watkins Glen in July where he finished 7th, one lap down on the winner, Brian Redman. The next event was Elkhart Lake in the end of July, but disaster struck when Schuppan suffered a suspension failure during a heat race that sufficiently damaged the car that it could not make the final. However, in the next round at Mid- Ohio, Schuppan got back on track, finishing a solid 5th behind the Lolas of Redman, Unser, Hobbs, and the Shadow of Jackie Oliver.

After Mid-Ohio, the AAR team elected to skip the next round at Road Atlanta to concentrate on the season-ending West Coast races at Long Beach, Monterey, and Riverside. While it is not clear what the reasoning behind this move was, it is possible that one explanation might be Dan Gurney’s involvement in the creation of the first Long Beach Grand Prix street race, which was being run for F5000 as a precursor to Formula One the following year. Whatever the reason, it seemed to pay off.

When the track at Long Beach opened for its very first practice, the first car to ever turn a wheel on the course was Schuppan in the 755. In fact, previous to that, Gurney himself had taken the 755 out on the track the day before to make sure the course was up to his standards as the event’s Director of Operations. In his heat race, Schuppan finished a promising 4th and as a result lined up 7th for the start of the inaugural Long Beach Grand Prix on September 28th. The race proved to be one of attrition with many cars retiring after being subjected to the pounding that only a temporary street course can provide. However, Schuppan and the 755 hung in there and finished in 2nd place behind the Lola of – you guessed it – Brian Redman. While this result was likely a welcome reward for Gurney – after all the hard work he put in to help bring the race about – it ultimately proved to be the car’s only podium finish in 1975. Unfortunately, Schuppan crashed out of the next race at Monterey with a right front suspension failure and in the season-ending race at Riverside finished 9th, one lap down on Andretti’s winning Lola. After showing so much promise in its debut with Hunt in 1974, the performance of the 755 during the 1975 season proved to be a bitter disappointment for the AAR team. Gurney summed up his feelings in Karl Ludvigsen’s book on the Eagles when he said: “This has been a sobering experience for AAR after so much success in Indy racing… Our inability to follow on with a similarly successful F5000 car has been rude to our reputations, has had disruptive effects on about eight different drivers, and has caused the collapse and reorganization of the AAR design staff.” With the eventual cancellation of the Formula 5000 series after the 1976 season, the brief saga of the Eagle F5000s came to a star-crossed end, with Schuppan’s 2nd place at Long Beach, being one of the F5000 Eagle’s last and finest results.

Flying with an Eagle

My opportunity to get behind the wheel of an Eagle F5000 came at VARA’s recent Formula Festival at Las Vegas Raceway. My car for this test was the one and only 755 that had been raced by the likes of Hunt, Unser and Schuppan – fairly big driving shoes to try and fill! The car was purchased by Tom Malloy in 2000 directly from Vern Schuppan and has remained in remark- ably original condition.

On first approach, I was struck by the car’s slender, streamlined good looks and distinctive robin’s egg blue paint scheme, which was characteristic of all the Jorgensen sponsored Eagles. After a brief discussion with Malloy about what things to do, and hopefully not do, I suit up and lower myself into the Eagle’s cock-pit. While I needed to sit directly on the tub in order for my knees to fit under the dash bulkhead, I was somewhat surprised by the sensation of sitting very deep in the car, or rather that the fiberglass cockpit surround sits very high. While sitting directly on the aluminum tub is never particularly comfortable, the overall seating position in the 755 is quite nice, providing the driver with a sense of being insulated and protected, though there is, in reality, very little protecting you!

The steering wheel is offset to the left of center, presumably to provide a little more hand room for the gear shifter, though visibility of the gauges through it is good. With my allotted track time approaching, I waited for the jump battery to be plugged in, I switched on the ignition and auxiliary electrical fuel pump and paused for a moment over the one push button that makes all our hearts skip a beat. With a push of the starter button, 525 horses woke up from their slumber and, from where I sat, they sounded big and they sounded mean. I know I’ve said this before, but there is simply nothing more visceral – more primal – than a race-pre- pared V8 motor. With each “blaaah” I hear in response to my jabs at the accelerator, my brain seems to go deeper and deeper into some primitive animal mode. The aural and tactile sensations that this type of engine creates is like the world’s most powerful narcotic drug – one shot and your hopelessly addicted. And just like a lab rat in some strange sort of addiction experiment, you can’t help but continue to press down on the lever that gives you more of what it is you crave!

With the green light given, I depressed the heavy clutch pedal, snicked the gearshift towards me and back to select first gear, squeezed on some revs, gently let out the clutch, and pulled out of the pit lane. As we took some of the on-track action shots that you see on these pages, I took a few “quasi-calm” moments to settle into the car and get a general feel for it. With virtually no bodywork beyond the front half of the tub, visibility forward and to the side is excellent. The view looking forward is one of a very slender, arrow-like car with almost nothing in your field of vision except the front wheels. However, looking out the rear view mirrors – which are dominated by the massive 17 ̋ rear tires and an enormous wing – the back end of the car gives the impression that it is 20-feet wide and that you better take that into account when you go into a tight apex!

With our photos now finished, it’s time to try and understand what Schuppan and friends were dealing with in 1974 and ’75. As I turned onto the Vegas’ front straight, I squeezed on the gas in first gear and begun rocketing down the track. While the engine will spin to 8000 rpm, I chose to shift at a cautious 6500 rpm, which is more than enough to flatten your eyeballs as you catch second and third gear before the first turn. I downshifted back to second for the first turn, snatching a quick, immensely satisfying blip on the throttle before catching the gear and getting back on the gas. The engine began to load up a little as I tried to accelerate out of Turn 1 so I feather it a bit, let it catch up and then surged back up to third before the next turn. This process continued for much of the first lap, with the car loading up coming out of the turns, until I finally took a stab at going back down to first for one of the final tight turns. Warp speed, Mr. Sulu! What I didn’t realize initially (and could not confirm until later) was that the Eagle had been set up with the gears that Malloy had used at Road America – first gear was good for almost 65 mph! With this problem solved, the Eagle now launched out of the turns with new- found ferocity. As I began to reel off faster and faster laps, I quickly came to realize that the 755 is very “hyper” at high speed. As I roared down Las Vegas’ two long straights, I became very cognizant of the Eagle’s tendency to want to zip and dart around with every ripple and undulation in the road. Since I wasn’t planning on testing the outer edge of the Eagle’s capabilities, I can only imagine what it must have been like to try and control this car at Elkhart Lake or the end of Long Beach’s long Shoreline Drive. In fact, it’s not until you get a chance to sample a car like this that you fully understand how talented (and brave!) drivers like Hunt, Unser, and Schuppan were in the day.

Owning an Eagle F5000

In the case of the 755, owning one shouldn’t be much of a concern since there is only one – and from the look on Tom Malloy’s face when he talks about it – it isn’t going to be for sale any time soon. With that in mind, the value of the 755 is probably the highest of all the Eagle F5000s due to its history and handful of podium finishes and is likely in the neighborhood of $70,000. While four examples of the 73A were built, these would likely command a slightly lower price due to their relative lack of competitiveness.

Grounded Eagle

Even before the 1975 season began, change was in the air at AAR. Feeling that he needed to make a dramatic change to his F5000 program, Gurney let designer Slobodynskyj go in the Spring of ’75 and promoted his assistant, Gary Wheeler, to the post of Chief Designer. According to Wheeler, Dan was ready to start with a completely clean sheet of paper and wanted to design a revolutionary new F5000 car. Wheeler devoted much of his time to the new car, the 765, throughout 1975. By the time the radical new car was finished it featured: a front-mounted radiator; full width nose and smoothly curved bodywork designed to help manage air flow to the rear wing; larger section modulus monocoque for better torsional rigidity; and, in contrast to the two previous cars, suspension geometry that allowed for a high static ride height and nearly 9 ̋ of suspension travel.

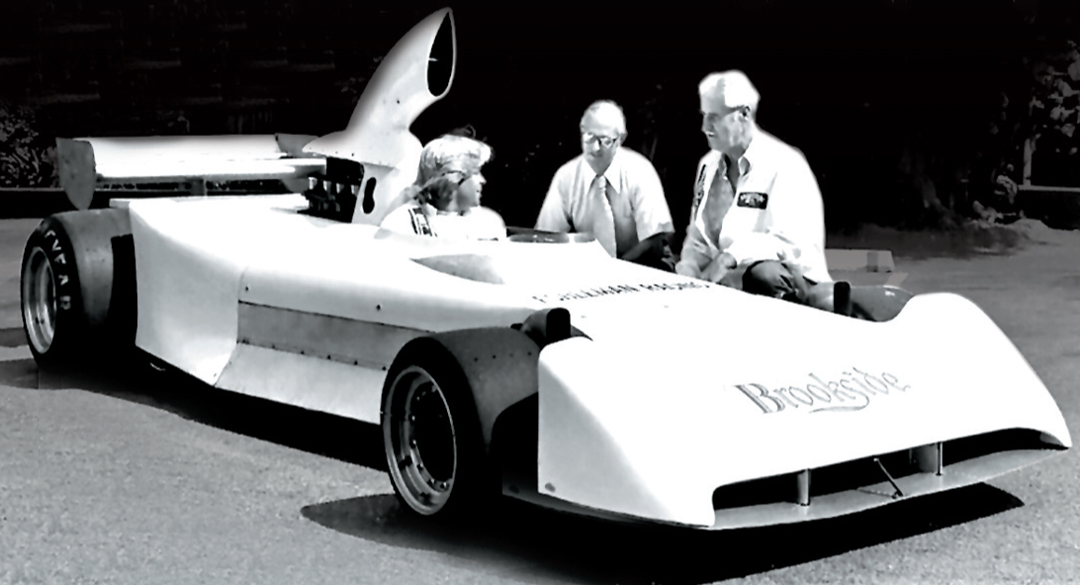

However, the new 765 never saw the light of day. Wheeler explains, “We pretty well finished the car on a Friday and I left for the weekend, thinking on Monday we would roll it out and take some pictures. Well, something happened later that afternoon that upset Dan enough that he disassembled the car over the weekend, had the pieces stored over the top of the AAR engine shop and that was the end of the 765. ̋ According to Gurney, the reason the car was shelved was that it was getting late in the season and the car was suffering from several problems. Later the 765 would be bought by Dave Eshleman and reassembled as a show car for Brookside Wineries. While the 765 has yet to be raced, Eshleman still owns it and hopes to have it restored one day for vintage racing.

Specifications

Wheelbase: 8 ́ 9 ̋

Track: 5 ́ 3 ̋

Length: 14 ́ 7 ̋

Weight: 1500 lbs.

Suspension: Front: Independent a-arms with Koni coilover shocks and anti-sway bar. Rear: Independent, parallel links with twin radius rods and Koni coilover shocks and anti-sway bar.

Engine: 302 cu.in. Chevy small block V8

Horsepower: 525 hp

Induction: Lucas mechanical fuel injection

Gearbox: Hewland DG-300, 5-speed

Brakes: Airheart calipers with 10.15 ̋ discs.

Fuel Capacity: 30 gallons

Wheels: Front: 13 ̋ x 11 ̋. Rear: 13 ̋ or 15 ̋ x 17 ̋

Resources

Gurney’s Eagles Ludvigsen, K. Motorbooks International

1976 Road Racing Annual Lyons, P., Knepper, M., Gilligan V. Paul Oxman Publishing,

1975 ISBN 0-914824-04-X

Riverside Raceway: Palace of Speed Wallen, D.

Dick Wallen Productions, 2000

Oldracingcars.com

Special thanks go to Dan Gurney, Roman Slobodynskyj and Gary Wheeler for their help in piecing together the history of the F5000 Eagles and a special thank you to Tom Malloy and his team for their generous help in making the test drive possible.