Aston Martin DBR4/2

In Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, the tragi-comical Mr. Wilkins Micawber, despite his predicament, always had the most impeccable words of guidance and wisdom. In one part he takes his young and inexperienced tenant, Copperfield, aside and counsels him against being dilatory. Micawber says, “My advice is, never do tomorrow what you can do today. Procrastination is the thief of time. Collar him!” It’s a shame those in charge of Aston Martin’s Grand Prix car project hadn’t noted Micawber’s words. They were diametrically opposed to Micawber and more along the lines of the 1947 Peggy Lee song, “Mañana is soon enough for me,” for it was in the early 1950s when an Aston Martin F1, or rather F2 (Formula One ran to F2 regulations in 1952 and 1953) was first mooted, but the DBR4 wasn’t ready to race until the 1959 season. In their defense—if one were needed—at that time, sports car racing, with the Le Mans 24 Hours as its pinnacle, was eminently more significant in relation to car sales than Grand Prix racing. The new Formula One World Championship was very much in an embryonic stage with the inaugural race of the then seven-round series being at Silverstone in May 1950 and unusually including the Indianapolis 500.

Aston Martin

Photo: Jakob Ebrey

Since its conception and foundation by Robert Bamford and Lionel Martin at the early part of the 20th Century, the Aston Martin brand, and its racing success, had a somewhat rollercoaster ride with many highs and lows. The ebb and flow of the financial tide found the company shifting from the original partners through many hands including Bill Renwick, Augustus Bertelli, Lancelot Prideaux Brune and Sir Arthur Sutherland, until David Brown purchased it in 1946. While the Bertelli years in particular had the company sights set on racing and competition with great successes both at Le Mans and the Mille Miglia, financial constraints meant the company concentrated on producing road cars in the years immediately approaching the onset of war in 1939. As noted in many of our profiles, during the war years the British engineering and motor manufacturing companies concentrated on the war effort and Aston Martin was no exception.

History shows the David Brown years offered more racing success, but his original purchase of Aston Martin was purely arbitrary. In his foreword for the book, “Racing with the David Brown Aston Martins—Volume 1” by John Wyer with Chris Nixon, he explains, “One day in 1946 I saw an advertisement in The Times offering an unnamed sports car firm for sale. My enquiry revealed that the firm was Aston Martin and, shortly afterward—more or less on a whim—I bought it. I was in no hurry to go racing, as I felt the cars’ two-liter engine simply wasn’t powerful enough, but a few months later I was given the opportunity to buy Lagonda too, and did so, having convinced myself that the six-cylinder, 2.6-liter engine W.O. Bentley had designed for that company could make Aston Martin a race-winner.” For Brown, this was a personal purchase and outside the David Brown Engineering Company—the price, £20,000. At that time, the Aston Martin works were based at Feltham close to the Surrey border in England; a place familiar to them during their run of success during the Bertelli years and through to the 1950s and early 1960s. As the Lagonda premises in Staines had already been sold, the assets of that company moved there too, after being purchased by Brown.

Sir David Brown, whose “DB” initials prefix the various Aston Martin road and racing model numbers, was born in Huddersfield, Yorkshire. After his education he was apprenticed to the family business, David Brown Engineering Limited, founded by his grandfather in the mid-19th Century, which concentrated on the manufacture of gear systems. Fifty years after the founding of the company, they formed an alliance with the American Timken Company to produce and develop worm drive units under the name Radicon (now a standalone global brand). In the early 1930s, David Brown Engineering Limited allied with Harry Ferguson and began producing Ferguson-Brown tractors. While the partnership was originally convivial, like many strong-minded individuals their grievances, mainly based on design and development of the tractor, meant the two parted company. As can be seen later, this wouldn’t be the first time Brown saw a partnership dissolve.

Early Racing

Upon purchasing Aston Martin, David Brown had the brand name and the services of Claude Hill, whom he held in high regard, but tangibly there wasn’t too much in regard to machinery. Other than a prototype, the Atom that Hill had been working on throughout the war years and a few machine tools, which had lain dormant for some time, that was it! St. John “Jock” Horsfall, a successful racer in the UK and Europe in his “Black Cat” Aston Martin 2-liter Speed Model, was recruited to assist Claude Hill. Horsfall was also a competent test driver and his skills were required to put the Atom prototype through its paces. Many miles of testing in all weather were undertaken in the simple body-less vehicle. To cement his views, Horsfall wanted others to test the prototype, so he asked fellow racers Tony Rolt and Freddie Dixon. They were enthusiastic about the car’s promise, so much so that Hill thought it was time to build a new chassis to enter in the upcoming Spa 24-hours sports car race. However, Brown was more subdued and had certain reservations. First, he thought time was too tight to build a new chassis, second he thought the two-liter, four-cylinder, pushrod engine wasn’t up to the job, despite others’ enthusiasm. In the end, Brown relented and confirmed his racing team, including John Eason-Gibson as team manager, Jack Sopp and Fred Lown as mechanics and body designer Frank Feeley—the latter trio being from Lagonda. The drivers were “Jock” Horsfall and Leslie Johnson. Surprisingly, the car won, dispelling any adverse thoughts Brown may have had.

The relationship between David Brown and Claude Hill became tense as Hill’s successful Atom racing prototype became dubbed DB1, and was further strained as the new DB2 cars were fitted with a Lagonda six-cylinder power plant. Hill had been, and was still, actively developing his own six-cylinder engine and took this as a personal slight, which ultimately resulted in his leaving the company. Three DB2 cars were entered in the 1949 24 Hours of Le Mans, two 1970-cc powered cars, the Arthur Jones and Nick Haines #27 finishing 7th overall and 3rd in class while the #28 car of Pierre Maréchal and “Taso” Mathieson crashed—the unfortunate Maréchal losing his life. The third car, #19 driven by Leslie Johnson and Charles Brackenbury and powered by the Lagonda 2580-cc engine, retired with water pump issues.

For 1950, a new face was added to the Aston Martin race team, John Wyer—albeit his initial contract was just for one year, he stayed until 1963. Brown had first been attracted to Wyer by his precise and efficient running of Dudley Folland’s pit at the 1948 Spa 24 hours—Folland was racing an Aston, too. Wyer soon added the names of George Abecassis, Reg Parnell, Eric Thompson and Jack Fairman to the already signed Lance Macklin and Charles Brackenbury. Fairman crashed on the way to Le Mans and was replaced by John Gordon. It wasn’t all doom and gloom, however, as Abecassis/Macklin and Brackenbury/Parnell finished 1st and 2nd in the 3-liter class, but the Thompson/Gordon car failed with a broken crank on the 8th lap. Sports car racing, particularly Le Mans, was the ultimate goal for Aston Martin, and although the new Formula One World Championship had been inaugurated in Wyer’s first year with the team, it wasn’t seen as a priority. Of course, although sports car success came in other great races with the team attracting top-line drivers such as Stirling Moss, Tony Brooks and Peter Collins, to name but three, it wasn’t until 1959 that Roy Salvadori and Carroll Shelby broke Aston’s duck at La Sarthe. More frustratingly, British rival Jaguar had racked up five wins, one with the XK120C (1951) and the C-Type (1953) and three more with the D-Type (1955, 1956 and 1957).

The Grand Prix Car Project

Ultimately, the first attempt at an Aston Martin F1 was abandoned. The chassis was broken up and the engines sold to John Heath. Eberan von Eberhorst was not overly excited about the new engine regulations for the 1954 Grand Prix season and although a much lighter DB3S chassis was produced and a 2.5-liter engine installed, the project was once again shelved in favor of sports car events. During the 1954 season, Eberan von Eberhorst left Aston Martin and returned to Germany to work for Auto Union once again, but the Austrian rarely settled in a position for any length of time and finished his career at the Combustion Engines and Automotive Engineering Institute at Vienna University prior to his retirement in 1965.

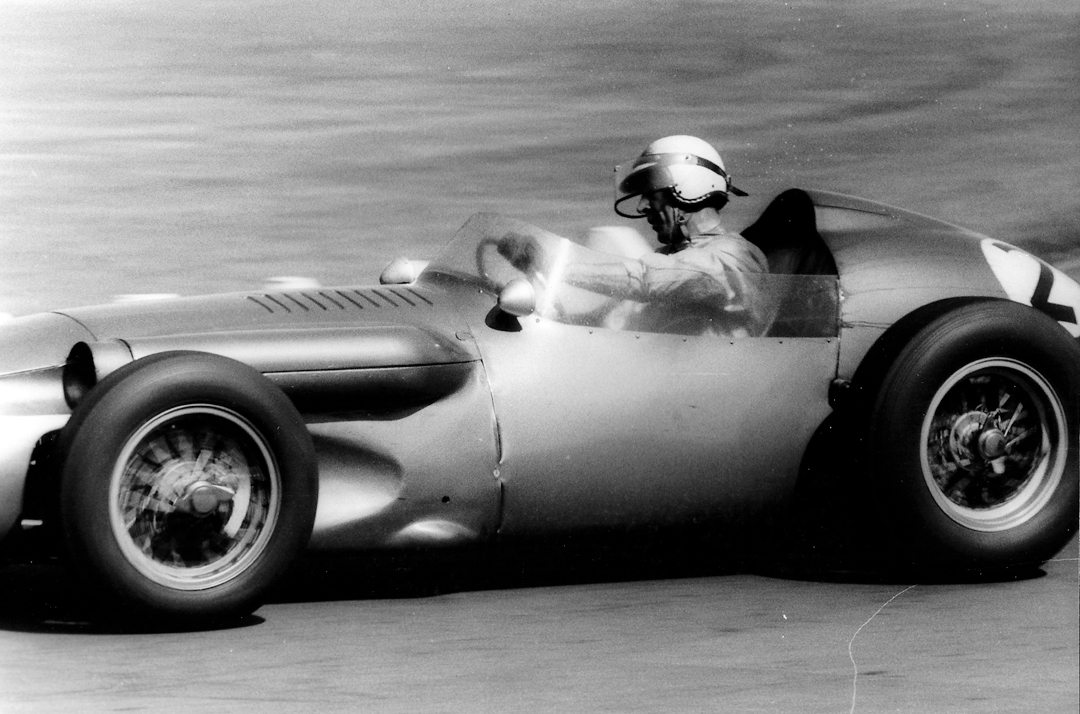

Meanwhile, the Mercedes W196 completely dominated Grand Prix racing in 1954 and into 1955, so Aston felt any attempt by them to compete would be pretty futile. Needless to say, the Le Mans tragedy of 1955, led Mercedes to withdraw from racing and opened the door once again for the Italian Maserati and Ferrari marques to return to the fore. Always ambitious, Reg Parnell asked Wyer if he could resurrect the defunct Grand Prix car, left covered in the factory since work ceased on it in 1953. Parnell’s idea was to take the car to New Zealand for the winter racing series, including races at Ardmore and the Lady Wigram Trophy at Christchurch. The car lacked a transaxle transmission and time constraints precluded any idea of construction. This meant the driving position would be directly over the driveshaft, not ideal as it meant the seating position was far too high. At Ardmore, disaster struck with Reg breaking the engine in practice—a rod went through the side, so racing the car there was abandoned. Parnell faired much better at Christchurch finishing 4th with a new engine fitted.

DBR4

Photo: Kary Jiggle

Like Ferrari, Aston Martin worked on a new sports car and Grand Prix car at the same time. And, also like Ferrari, the sports car always took precedence over the single-seater. So, in 1955, DBR4 and DBR1 began life under the same roof. There had been a change in the company management structure about that time too. During the latter part of 1956, John Wyer had been made General Manager of the whole of the Aston Martin Lagonda outfit. It was clear the nature of this new appointment left him unable to continue as Racing Manager. With Reg Parnell—who had raced so successfully for many years and was considered Britain’s leading participant in the sport—deciding to hang up his helmet and goggles, Wyer saw him as his ideal replacement. The two had become good friends over the years and Wyer held Parnell in very high esteem. In his book The Certain Sound, Wyer comments on the appointment, “I thought—and events proved me right—that he would be a great commander in the field and that his relationships with drivers and mechanics would leave little to be desired.” Wyer looked upon the task of running the racing team as a regimental military exercise, while he saw Reg’s strengths, he also saw his weaknesses too—paperwork being the main. Gillian Harris was appointed as his secretary and administrative assistant, or as Wyer puts it, “Reg’s Chief of Staff.” Parnell’s nephew Roy, who had worked in the experimental department since 1953, became his deputy and Crew Chief.

With the racing division now sorted, problems arose in the finances—not an unusual problem for Aston Martin. The biggest difficulty was that the company was producing too many cars that no one really wanted. Extraordinarily, in today’s thinking, at that time the cars lacked that certain something and didn’t appeal to the public. Wyer’s move to General Manager was more a point of desperation for the company as he began a worldwide tour to countries including Australia, New Zealand and the USA to boost sales. The continuance of car production was simply to keep the very valued staff. Wyer returned to the UK with the words of Kjell Qvale, Aston Martin Lagonda’s San Francisco distributor, ringing in his ears, “Win Le Mans and then we can sell some of your cars.” The comment cemented the “shelving” of the DBR4 project and an acceleration of the DBR1. Having said that, 1957 brought the completion of the first DBR4 chassis. Basically, the car was a derivation of DBR1, but obviously with a lighter and narrower multi-tube chassis, fitted with a 2.5-liter RB6 engine. David Brown saw Vanwall stealing the Grand Prix limelight and dearly wanted to get his DBR4 car onto the grid for 1958. Up until that point, Grand Prix cars had been able to run on alcohol fuel, but starting with the 1958 season, only petrol was allowed. This played into Aston Martin’s hands as its engine was purely developed with petrol. An engine test at MIRA, over the Christmas-New Year period of 1957-1958, produced very promising results for the new car, now known as DBR4/250, and Tony Brooks had been involved in road testing around the Lindley circuit. With this news all was set for a Grand Prix challenge, but once again sports car racing got in the way. From the 1958 season, the CSI had restricted the engine capacity for participants in the World Championship for Sports Cars (WCSC) to three liters. DBR1 was already the fastest three-liter sports car in the world, so it was thought an all-out attack on the WCSC, which included the 24 Hours of Le Mans, was their time to strike. After all, success, particularly at Le Mans, would surely get car sales moving?

The DBR4 project was set aside—a fatal error in the development of the Grand Prix car. Indeed, in hindsight, John Wyer admitted the company had probably walked away from the only season where DBR4 could have stood any chance of victory—the only viable competitive challengers were Ferrari and Vanwall, and DBR4 had proved in testing to be faster than both. The driver lineup was strong too, Reg Parnell talking Stirling Moss back from Maserati, Jack Brabham, Roy Salvadori, Tony Brooks, Carroll Shelby and Stuart Lewis-Evans—so, no lack of talent there. While DBR1 enjoyed a race speed advantage, it did lack endurance. Despite this all-out attack on sports car racing, retirements at Sebring, the first race of the season, set the tone for the season. Victory at Goodwood’s Easter meeting, a 1-2 at Oulton Park, victory at Nürburgring and a season finale 1-2-3 at Goodwood’s Tourist Trophy was the best the team could do. Once again, a Le Mans victory eluded them with early retirements from the Moss/Brabham car with engine problems, the Salvadori/Lewis Evans car crashing, and both before 50 laps had been completed, leaving the Brooks/Trintignant car as the only contender. Unfortunately, with their gearbox ironically failing on lap 174, it was a case of packing up and looking forward to 1959—a do-or-die year.

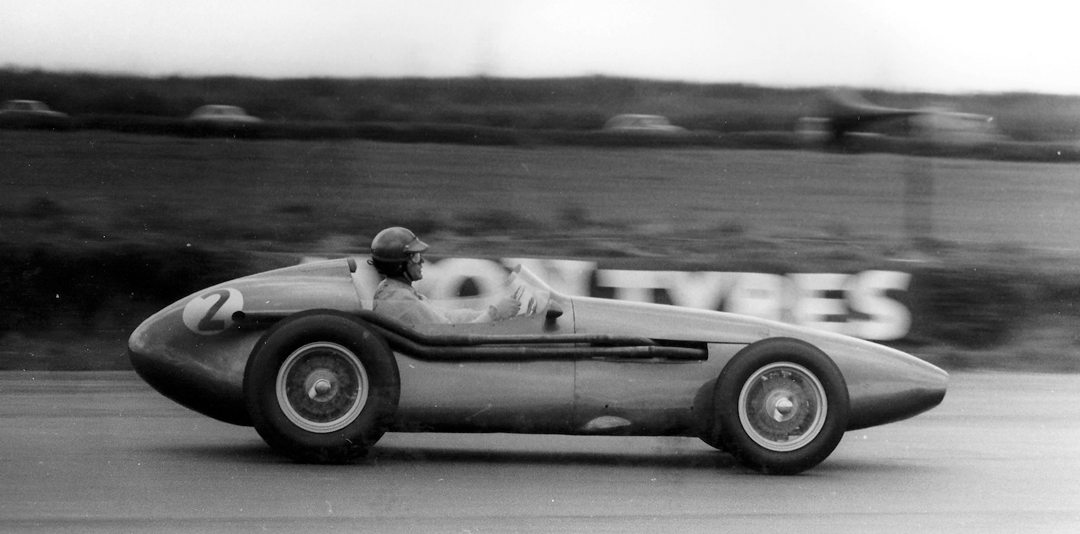

That was the dawn for DBR4 to hit the track for its first competition. In Formula One then, just as now, if you stand still you go backward, and at a very rapid rate. Cooper had worked tirelessly developing its new rear-engined, and very light, T51. It was already showing good promise, and was ultimately proven the way to go in Grand Prix racing. The services of Jack Brabham and Roy Salvadori were orally agreed for the Aston Martin inaugural assault on the 1959 F1 World Championship. Both drivers had previously raced for Cooper in Formula One, Salvadori being team leader. John Cooper wanted both drivers to remain with the team, and did all he could to persuade them to remain. Esso’s Reg Tanner played a vital part by increasing Jack Brabham’s retainer to stay with Cooper. With that and the promise of a new powerful engine, Brabham chose to remain at Cooper and the rest, as they say, is history. Roy Salvadori was already on a high retainer at Cooper for the Grand Prix season, but he was quoted as saying in period, “Money was not a factor in my choice of team for 1959.” Reg Parnell had convinced Salvadori that the Aston Martin Grand Prix budget was higher and their test and development record much better than Cooper—he should also show some loyalty to the team that had shown faith and given him an opportunity to race for the past six years. In the end, Salvadori stayed with Aston Martin, and his good friends Reg Parnell and John Wyer. In fact he reportedly said, “I had been happier in that team than any other.” With Brabham’s departure, a new driver was required and American Carroll Shelby seemed to fit the bill, so he was signed to race alongside Salvadori for the season.

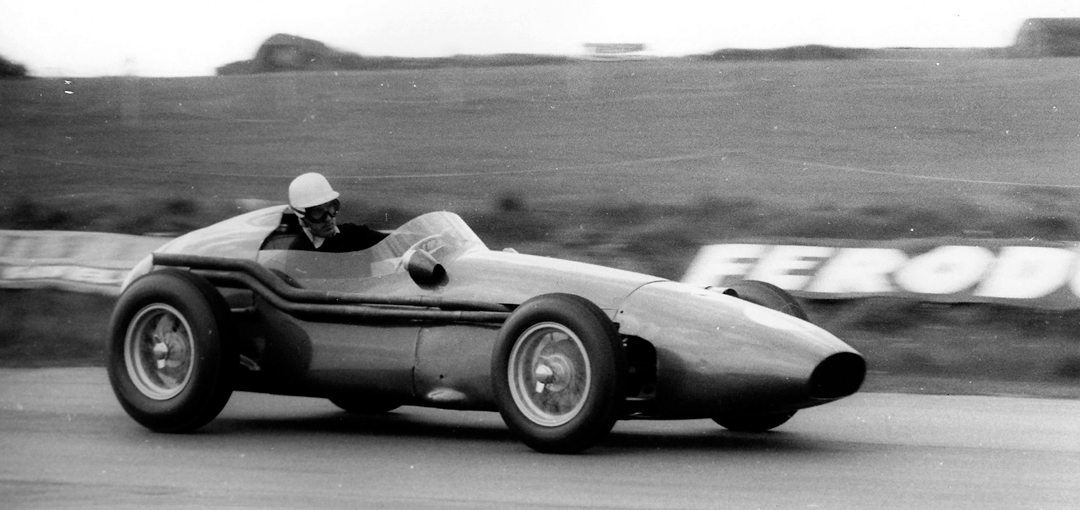

The first competitive outing for the two DBR4 cars was at Silverstone’s International Trophy race in the first weekend in May. The two cars displayed side-by-side in the paddock, although new, looked rather dated—especially when in company with the new Cooper T51. Designer Ted Cutting had redesigned the suspension in line with John Wyer’s thinking. The front was now more like the DB4 and the rear more like DBR1—a three-piece de Dion tube with longitudinal torsion bars, the DBR1 CG537 transaxle was also used. The team was quite upbeat after first qualifying, with Salvadori just a fraction off poleman Moss’ BRM P25 and 2nd qualifier Tony Brooks’ Ferrari Dino 246. The Aston had recorded a 1:40.4, for 3rd spot—ironically the exact same time as Brabham’s Cooper in 4th—to complete the first row of the grid. Carroll Shelby was in 6th place in the middle of the second row of the 4-3-4 grid. In the race, Shelby retired with engine problems after losing top gear early in the race, but Salvadori finished 2nd to winner Brabham, albeit some 17 seconds adrift, but had set a new lap record of 1:40.0, or 105.37mph. Weekly UK motor racing magazine Autosport reported: “Greatest talking point after the BRDC International Trophy meeting at Silverstone last Saturday was the outstandingly good performance of the new Formula One Aston Martins—one of the most encouraging debuts ever made by a British contender.”

However, back at the factory, the autopsy took place on Shelby’s engine—it had blown and lost all the bearings. On examining Salvadori’s car, it was found his engine wouldn’t have lasted much longer as the overlay had come off of the bearings. The engineers put the problem down to pure engine speed as the 2.5-liter RB6 engine had only been used to running at 7,500 rpm top speed, while at Silverstone, the engines were running at 8,000rpm and above. The drivers were told not to exceed 7,000 rpm in future races. Aston was already on the back foot. Quite late in the 1959 season, Glacier Metal eventually thought it had identified the problem and found the root cause, but this was just an expensive “red herring”—they thought the con-rods weren’t strong enough for the Glacier bearings, but even after stronger con-rods were manufactured the problem still existed. An Aston engineer eventually found the answer—the crankshaft drillings were cutting off oil supply, simply by making these drillings just off top dead center cured the problem. It really was a dreadful season full of what might have been if only they’d not dithered with the project. John Wyer eloquently summed up the whole Grand Prix saga, “The DBR4, which might have won races in 1958, was a dying duck in 1959 and a stinking fish by 1960. At Monza, in September 1959, our cars weighed 1,400 pounds, which was respectable by the standards of Ferrari, the 250F Maserati and the Vanwall, against which we would have been competing in 1958; at the same race the Cooper weighed 1,190 pounds and the new Lotus 1,080. John Cooper and Colin Chapman were busy driving nails into the coffin of the front-engined car.”

DBR4/2

The original DBR4/2 debuted, as mentioned above, at the BRDC International Trophy race in early May 1959 and was considered as Carroll Shelby’s racecar. With significant engine problems, it was more or less a “back to the drawing board” moment for the team. The Aston Martin DBR4s didn’t grace a World Championship round again until the Dutch GP at the end of May. The Monaco GP on May 10 was far too soon, and the Indy 500, which was then part of the F1 World Championship, wasn’t usually contested by the regular Grand Prix drivers. So, in Holland the bitter truth was finally revealed to the team, they were simply too far off the pace—Shelby some 2.5 seconds. His time got him a 4th row, 10th place grid spot with a time of 1m38.5s. Shelby’s race was once again ended by engine failure—the bearings had failed just as at Silverstone. Missing the French GP and returning for the British GP at Aintree, in July, the cars were once again much slower than other competitors, there was an added problem too—fuel was splashing into the cockpit from the tank. Reg Parnell had told both drivers to expect a spot here and there during the opening laps, but as the tank emptied it should not be a problem. On lap two of the Aintree circuit Shelby was sitting in a pool of petrol and made a pit stop—much to the irritation of team manager Parnell. Returning to the action it wasn’t long before Shelby came back in with ignition failure—his race was over. The car, while slow, was said to have tremendous braking and remarkably stability in the corners. If the acceleration had matched the braking, the Feltham team would have been flying!

The penultimate World Championship race for DBR4/2 was in Portugal, the team again missing a round—Germany. The Monsanto Park circuit just outside Lisbon was made up of varying types of surfaces including cobbles, tarmac and even tram-lines in certain places— it was to be the first and only time the Grand Prix circus visited the venue. On the grid, the DBR4s were side-by-side in 12th and 13th places—Shelby’s chassis 2 taking the “unlucky” position, however, with an 8th-place finish, Shelby may have considered the spot lucky. For the first time the cars were seen at consecutive races and lined up at Monza. Now both cars were nearing the back of the grid, of 21 starters Shelby in DBR4/2 started 19th, with a 1m46.4s and teammate Salvadori in the new DBR4/3 car was 17th, 1.7secs quicker. Shelby finished his last race in the car in 10th position he could see the writing was on the wall for Aston Martin in F1.

What happened to the car after that is not really known, some records suggest it was scavenged to build the new DBR5, others simply say by 1961 it was scrapped. Whatever, after a break of around 20 years, and already having DBR4/1, Aston Martin enthusiast Geoffrey Marsh approached the UK’s Vintage Sports Car Club (VSCC) with a view to recreating DBR4/2. When purchasing DBR4/1 and also DBR1, Marsh had acquired an enormous amount of original Aston Martin components, including a 2.5-liter 95-degree cylinder head and a David Brown transaxle. Marsh’s Marsh Plant Specialist Car Division set about rebuilding DBR4/2 to the same design and specification as the original car. Once completed, in July 1982, the car was vetted by the VSCC and accepted as a Group IV Historic Racing Car. Goodwood was the venue for the first shakedown test in October 1982 and, barring minor grumbles with the gearchange, it performed well.

One of the first public appearances was at the 1984 “Streets of Birmingham” historic racing car parade when the two original Aston Martin F1 team drivers, Roy Salvadori and Carroll Shelby, were once again re-united with their DBR4 cars. Since that date, the car has passed through a number of hands and raced very successfully in historic events by many notable and regular racing drivers. It has, of course, undergone further restorative care—the last being by Mike Williams and his team at Beaufort Restorations in the early 2000s. It was last seen out at the 72nd Goodwood Members’ meeting in 2014.

Driving DBR4/2

At first sight, DBR4/2 transports you back to a bygone period when front-engined racing cars ruled. Memories of a “golden era” of drivers like Fangio, Moss, Collins and Hawthorn stir in the mind, but unfortunately that was the failing of the car. By design, it was a car out of kilter with new thinking, technology and the way ahead for Grand Prix racing. It’s clear that not only did the physical car stand still, but the minds of those who considered racing it stood still too. Nevertheless, for the purpose of this test drive, we’ll need to clear our mind of that fact and instead dwell upon the attributes of the car itself. As the DBR4s debuted at Silvertone’s International Trophy race in 1959, it would only seem right to revisit the same venue for our test. Since 1959 the circuit has undergone many changes, including the Grand Prix track layout, which has not only increased in length by some ¾ of a mile, but almost doubled the amount of corners.

Weather-wise, it’s a good day for motor racing—clear skies, good ambient temperature and a dry track. The car has been readied by the mechanics and is ready to go with optimum temperatures and pressure of fluids. The first, most noticeable thing, as we climb aboard, over the twin hot exhaust tail pipes, is the roomy cockpit—not something racing cars are usually endowed with—the last thing on a designer’s mind is driver comfort. Thank you Mr. Cutting. Another is the lack of a roll-over hoop. Again, most historic racecars today have extra “scaffolding” fitted for driver protection, but not this car. Lastly, there are no seat belts! So, from a health and safety point of view, we are most definitely back into 1950s racing mode.

It’s fairly easy to sit comfortably, but I can anticipate the necessity of padding for a smaller driver. Sitting astride the offset driveshaft cover, the left leg and foot are guided toward the clutch pedal. On the right there’s just a little more room for your foot to easily operate the brake and accelerator pedals. The large, thin, three-spoke steering wheel allows ample visibility of the gauges—a large center rev counter, with the red tell-tale needle set a little over 6,500 rpm. To the left, is a small oil pressure gauge, to the right, at the top, is the water temperature and below is the fuel pressure. The Perspex wraparound screen offers unobstructed vision of the front wheels, of course, we’re sitting quite proud of the top so outside the cockpit we have a clear view, too.

Like most tests, we’ve completed a couple of exploratory laps warming the tires, brakes and the like. We’re gently trying to form a relationship with the car and generally getting to know it before driving a lap in relative anger. Up to this point, it has proved well balanced and responsive. As we’re using the original pit complex at Silverstone we start the lap after exiting Woodcote. Cutting Woodcote quite sharp gives us a straighter line across the start/finish line—with this car the straighter it is and the earlier we can get it onto the straight the faster our lap time will be, that’s the real secret with this 2.5-liter engine. As we start the lap we’re in fifth, top gear, to give us ultimate speed.

Approaching Copse, we lose a gear not only to take the right-hander, but also to give us power to negotiate the incline from the exit of Copse up to Maggots. Staying in fourth gives peak performance into Becketts and the complex of corners prior to getting onto the Hanger Straight. At this point, the lower gear is preferred as there’s not too much torque in the 2.5-liter engine—other cars, especially with three-liter engines, would take top gear prior to Maggots, but keeping the lower gear suits this car.

As the track meanders left-right-left, you can appreciate the superb road holding of the DBR4. Now on the fastest point on the circuit, Hanger Straight, we’re in top and pulling around 6,800 rpm. Soon, we’re approaching the marker boards for Stowe, so we start to scrub off speed and lose a gear through the right-hander, once again there’s a change in elevation—Silverstone is considered flat, but don’t believe it, there are many elevation changes on this new Grand Prix circuit layout that will catch you out. Approaching Vale and the 180-degree Club corner we again scrub off some speed and change down a couple of gears. Vale and most of Club are taken in third, accelerating hard and changing to fourth as soon as we can. We’re certainly in fourth as we cross the start/finish line opposite the new “Wing” pit complex.

It’s possible to hang the tail out on the exit of Club just a wee bit, but not too much. Great care must be taken not to induce the “pendulum effect,” which can soon take hold if exiting too fast and too soon—many people have lost it here and had their first heavy meeting with the pit wall. Again, we’re traveling uphill approaching Abbey, which is now a right-hand corner—not a left, as the original circuit continued—taking third as we enter Abbey, we’re up to fourth gear again on exit and through the long, gentle Farm Curve. Down a gear, we’re now turning right and approaching The Loop, a second-gear hairpin bend that quickly opens up, allowing great acceleration as we turn onto the National Straight, and another opportunity to get up to top gear and maximum speed.

Approaching Brooklands, the sharp left-hander, we drift to the outside of the track to open up the corner to give maximum power and grunt through it. A quick gear-change sees us take third and almost immediately fourth as we exit Luffield 1 and onto Luffield 2. At Luffield 1 we hug the right apex, but we turn late into Luffield 2 to allow us to get maximum power through the corner, we’re in fourth through Woodcote and looking for top just as we complete the lap.

Overall, the driving is safe and secure and the car holds the road very well, you can “play with it” a little and induce opposite lock at certain places, using the brakes the car will “dance” for you. In traffic, the car is equally responsive and handles well, but this is against other front-engine cars in the main. The thing that lets it down is the underpowered 2.5-liter engine and a lack of torque. Yes, in period, they tried the three-liter on the 1960 DBR5s, but that was too little, too late. Today, in historic racing, the three-liter DBR5s soon get the better of the DBR4s—but are in a different class.

So, the light, nimble and extremely powerful Cooper and later the Lotus rear-engined cars showed that the dinosaur front-engine cars’ time was up and there was a new way ahead. Like Aston Martin, Lance Reventlow’s Scarab fell similar victim. However, remember, this is an Aston Martin, regardless of the many missed chances and misgivings in period, the name and brand has that certain history and kudos that will always appeal to the marque’s many enthusiasts. While the DBR4s weren’t the way to go in 1959, in historic racing terms, today they offer a significant challenge.

SPECIFICATIONS

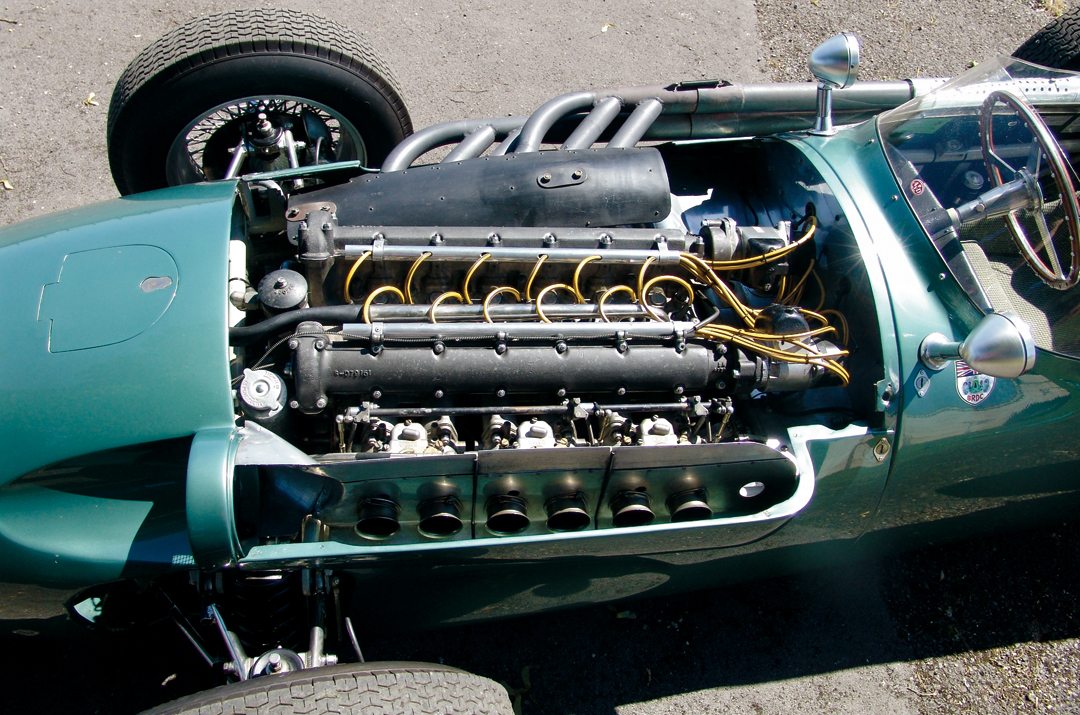

Engine: RB6, Straight-6, 2493-cc, 95-degree, DOHC with twin-choke triple Weber carbs, aluminum cylinder head and crankcase

Gearbox: CG537 DB transaxle

Brakes: Girling disc brakes all around. Front: 12.5-inch diameter, 1-pot caliper. Rear: 11.5-inch diameter, 1-pot caliper

Steering: Rack and pinion

Suspension: Front: Double wishbones, coil springs over dampers, Rear: DeDion axle, trailing links, transverse torsion bars

Track: Front: 51.5 inches, Rear: 51.5 inches

Wheels: Borrani. Front: 5.5 x 16, Rear: 7.0 x 16

Wheelbase: 90 inches

Length: 177 inches

Width: 66 inches

Height: 52 inches

Weight: 1378 pounds

Resources / Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Aston Martin—The Post War Competition Cars – by Anthony Pritchard The Certain Sound – by John Wyer

Racing with the David Brown Aston Martins – Volumes 1&2 – by John Wyer with Chris Nixon Roy Salvadori—Racing Driver – by Roy Salvadori

Reg Parnell – by Graham Gauld

Directory of Historic Racing Cars – by Denis Jenkinson

Publications

The Motor

Motor Sport

Autosport

Thanks

Vintage Racecar would like express sincere thanks to the following in assisting to prepare this piece: James Mitchell of Pendine Historic Cars, Bicester, Bicester Heritage

Barrie “Whizzo” Williams Ted Walker, Ferret Fotographics, and John Pearson for period photographs