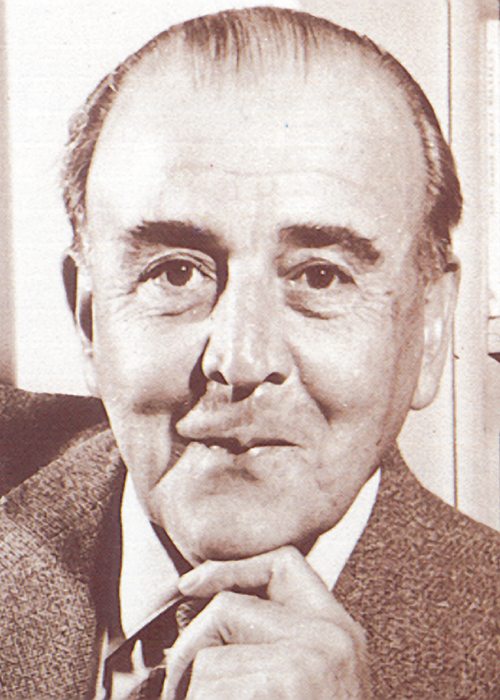

As I sat quietly in a pleasant house in Woking, England, in the winter of 1970, I watched and listened. My friend Brian Robbins, editor of BBC TV’s motoring programs at the time, was interviewing an 81-year-old man about his illustrious career. The little man was obviously ill, as he was swathed in thick pajamas and a heavy dressing gown, and a blanket lay loosely over his shoulders as he sat with his legs resting on a stool in front of a roaring coal fire. His name was Walter Owen Bentley, and he was a genius. He designed and built the powerful and luxurious Bentley cars, the specially tuned versions of which won the 24 Hours of Le Mans five times, four of them in succession.

The feat inspired Ettore Bugatti to call W.O.’s long, open cars the world’s fastest trucks. Sour grapes from another genius, but one whose cars only won Le Mans twice, in 1937 and 1939.

W.O. was born into what was then called a “well-off” family on September 16, 1888, in the London suburb of Hampstead. As their description suggests, his parents had money so they sent him to the exclusive fee-paying Clifton College in Bristol. Always fascinated by machines, W.O. got his first job in 1905 with Britain’s Great Northern Railway, where he learned to design railway engines and other equipment, a useful foundation for what was to come.

Bentley was also a keen motorcyclist and raced bikes, competing in the 1909 and 1910 Isle of Man TT, but was unsuccessful, as he did not finish either of them.

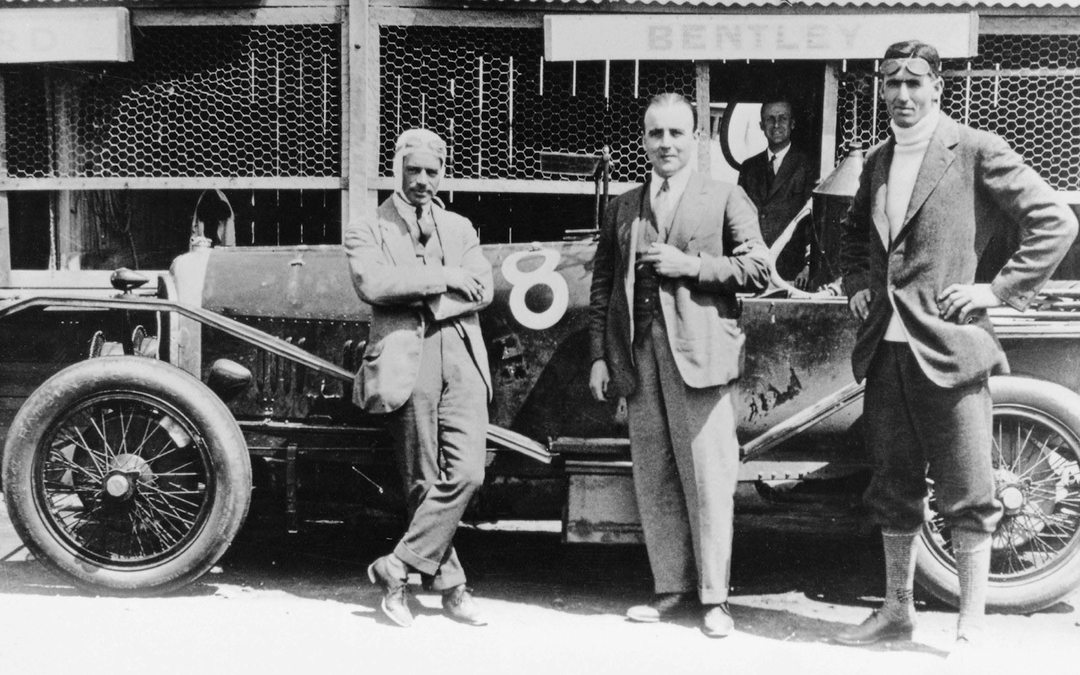

Photo: Bentley

W.O.’s father wanted the boy to buckle down and learn something useful, so the young man was sent to Kings College, London, where he studied theoretical engineering. Upon graduation, he went to work for a taxi company in the British capital, keeping as many of its 250 Unic cabs on the road as he could. That didn’t last long, though, because in 1912 he joined his brother Horace Millner Bentley in a company that sold French Doriot Flandrin Parant 2-liter 12/15 cars, tuned versions of which W.O. raced in hillclimbs and at Brooklands in 1913 and 1914.

The First World War put a stop to that, however, as W.O. was commissioned into Britain’s Royal Naval Air Service, where he put his mechanical knowledge to good use by contributing to the design of aircraft engines that ended up as the Bentley Rotary 1 and 2. After the war, he was awarded the MBE for his work. In 1919, W.O. and H.M. founded Bentley Motors Limited in a small factory in Cricklewood, London. The first Bentley to emerge from the works was the EXP 1, obviously an experimental model that more than one motoring journalist thought was brilliant. As W.O. was always looking for ways of doing better, he next came up with the

3-liter EXP 2 with which he won his first race at Brooklands with Frank Clement at the wheel. It was the 1921 Junior Sprint Handicap in which the Clement and the Bentley roundly beat stars of the day like Henry Segrave and Malcolm Campbell.

Racing was all very well, W.O. thought, but his main objective was to produce superior quality fast, luxurious touring cars. And he did just that, as a plaque in New Street Mews, off Upper Street, London, confirms. That was where he started up the first of his 3-liter Bentleys, a car that belched out an ear-splitting roar, and started road testing the roaring monster right away.

After his novice victory at Brooklands, Bentleys were entered in modest hillclimbs with W.O. at the wheel, won minor races and one of his cars even competed in the 1922 Indianapolis 500. Bentley’s Indy driver was 29-year-old Douglas Hawkes, who finished a creditable 13th and was the last car still running, after having completed the statutory 200 laps. Bentleys did better in that year’s Tourist Trophy with all three of the 3-Liters finishing. Frank Clement came 2nd, W.O. 4th and Douglas Hawkes 5th to win the team award.

Photo: Bentley

It took a lot of persuading to get W.O. to make the trip to Le Mans to see the very first 24 Hour race in June 1923. He didn’t think any car could withstand such a non-stop pounding for 24 hours over the unmade, pitted roads of the Circuit de la Sarthe, and thought the whole thing was crazy. Eventually he came around, though, and went to see the first of the famous races on May 22-24, 1923, mainly to see how John Duff and Frank Clement would get on in their privately entered 3-liter Bentley. They did well by taking 4th, which left W.O. open-mouthed, but keen to have a go with his works cars. Bentleys would eventually compete in a total of eight successive 24 Hours of Le Mans.

At the time, W.O. and his brother H.M. were doing well, with 1924 the best to date in 3-liter car sales. The development costs of the new 6.5-liter car were high, though, and the company’s financial position soon became somewhat precarious. However, the 6.5-liter turned out to be an outstanding car, and as W.O. was developing it he had racing in mind. John Duff, who came 4th in his own Bentley in 1923, was asked to drive one of the works cars in 1924. He was keen, but insisted on a harsh physical fitness program. And he practiced raising the car’s hood and snapping it back into place again to meet the new Le Mans regulations until he got the process down to 45 seconds. In those days, only the driver was allowed to work on his car, which included filling the fuel tank, as well as topping up the oil and water. Duff remembered the roughness of the 1923 Le Mans “circuit”, so for 1924 he lagged the petrol tank to protect it from flying stones and devised a wire grill for the front of the works 3-liter Bentley to shield the headlamps and radiator.

The race was run on June 14-15 with its now traditional 4 p.m. start, and was to cover 120 laps of the 10.76-mile circuit for a total of 1,287.12 miles, in which Bentley was the only non-French marque. There were some long faces midway through the race when Duff pulled up in the pits with a swollen hub and W.O. became even more concerned as the stop dragged on. The car got going again, however, and went so well that Duff and co-driver Frank Clement won by a lap from the Stoffel-Brisson Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6.

Strangely, at a private post-race celebration, there was no euphoric atmosphere in the dining room, but a sombre one, almost as if they had won nothing. That was because Bentley Motors was falling into worsening financial straits. So much so that the company needed a rich new owner to put it back on its feet. So W.O. and H.M did a deal with an established Bentley customer, 29-year-old Woolf Barnato, son of a South African diamond magnate, who pumped money into the starved business to become its new owner and chairman. Bentley Motors Limited moved to plush new offices, which a rather hurt W.O. didn’t like at all, dismissing them as being like London’s super-luxurious Savoy Hotel. But Barnato’s wealthy ways brought in the customers, who included a large slice of London society, actors, actresses and politicians. W.O. huffed and puffed over that, saying his company was to be renowned for its engineering prowess, not its flighty customers.

More than two years had passed since Duff-Clement won 1924 Le Mans, during which time Bentleys often did badly in British races and hillclimbs. That enraged chairman Barnato, so he imposed an almost military regime on his company’s attempt to win Le Mans again. A separate new racing department was built. The racing team was kitted out with all the latest mod-cons, right down to back up stopwatches for the time keepers. And drivers had to practice pit stops to get their times down to a bare minimum.

Preparation for the 1927 Le Mans steamed ahead with W.O. not allowing even the smallest mistake to slip by without correction.

The team turned up at Le Mans a week early and put in hours of practice, which included refueling with five-gallon milk churns—sometimes getting soaked in the process—and wheel-changing.

June 18 eventually arrived, although Woolf Barnato did not, as he was away on important business. So the Bentley contingent was comprised of Benjy Benjafield and Sammy Davis in 3-liter #7, Frank Clement and Leslie Callingham in the 4.5-liter and George Duller with a sharp-tongued Baron Andre d’Erlanger in another 3-liter, which finished its Le Mans by going off big time at White House. After 137 laps and 1,469 miles, Davis and Benjafield had won in their Bentley Sport at an average of 61.228 mph, and Clement had set the fastest lap on the 10.726-mile circuit of 8 minutes 46 seconds in the Bentley Super Sport. A triumph indeed.

That win was the making of Bentley Motors, even if only briefly. The fickle darlings of London society all wanted a road-going version of the car that won Le Mans, so the company’s finances took on a much more pleasing look.

The team continued to work and train hard for the 1928 Le Mans. W.O.’s car may have won the 1928 Le Mans again, but being a stickler for discipline, he noticed that there were too many “unwanted guests”—like the drivers’ girlfriends and family members—in the Bentley pits, so he issued an instruction for the 1929 race that only those authorized would be allowed in.

Believe it or not, the 1929 24 Hours of Le Mans was a rather boring race over a new track that did not take in the suburbs of Le Mans. The race was so slow that Glen Kidston actually stopped his 4.5-liter Bentley and called into the Café de l’Hippodrome for a drink! The whole thing was a walkover for the Bentleys, and it set winner Woolf Barnato on the road to making motor racing history. He and Tim Birkin won the race in a 6.6-liter Bentley Speed Six at an average of 73.186 mph. Second were Jack Dunfee and Kidston in the 4.5-liter, 3rd Benjy Benjafield and Andre d’Erlinger also in a 4.4-liter and 4th Frank Clement and Jean Chassagne bringing up the rear in the third Bentley 4.4.

Such glory, but at a price. Bentley Motors was all but broke by the time of its last Le Mans win, so the company was sold to Rolls Royce, but that’s another story.

By the time the BBC TV camera had stopped whirring, W.O. was all in, but he couldn’t resist showing the crew handsome models of all his Le Mans-winning racing cars before he was helped to bed by his housekeeper. After he left, both Brian and I had little to say to each other, as we quietly mulled over the labored answers of one of motor sport’s truly great men.

W.O. Bentley died soon afterward, on August 13, 1971 at the age of 82.