Automobiles first came to Los Angeles just over 100 years ago. Roughly 23 manufacturers eventually set up shop in the ensuing years and the region grew in concert with the relatively new invention, producing what we might rightly call the first auto-based city in the United States.

Novelty aside, early automobiles faced tremendous hurdles when first introduced. Folks were slow to give up their tried and true horse for a mechanical beast of questionable integrity.

Keep in mind, however, that the Los Angeles of 1908 was a very different place than it is in 2009. North/south transportation was limited to either ships or horse-drawn wagons traversing treacherous mountain passes. To the west lies the Pacific Ocean, and eastward was a vast, inhospitable desert. People who came to Los Angeles in those days were in search of a destination. They were not simply passing through and then decided to stay. They wanted a different life from that dictated by the Midwestern and Eastern vertical cities. They were willing to toss aside the 19th-century notions of American life and embrace the new century with everything they had.

Thus, the sleepy pueblo of Los Angeles found itself stocked with a vibrant, enthusiastic citizenry bent on establishing a new definition of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Advances in the auto industry just happened to appear alongside those of the entertainment industry and both found a home in Los Angeles.

How do you get your news? Where did you get the latest information about what interests you? No doubt you utilized some electronic form of information. The Internet, television, radio. What if those industries did not exist (let alone the myriad versions of each—sites, channels, stations, etc.)? That was the world of Los Angeles in 1908. That was the world in which Barney Oldfield thrived.

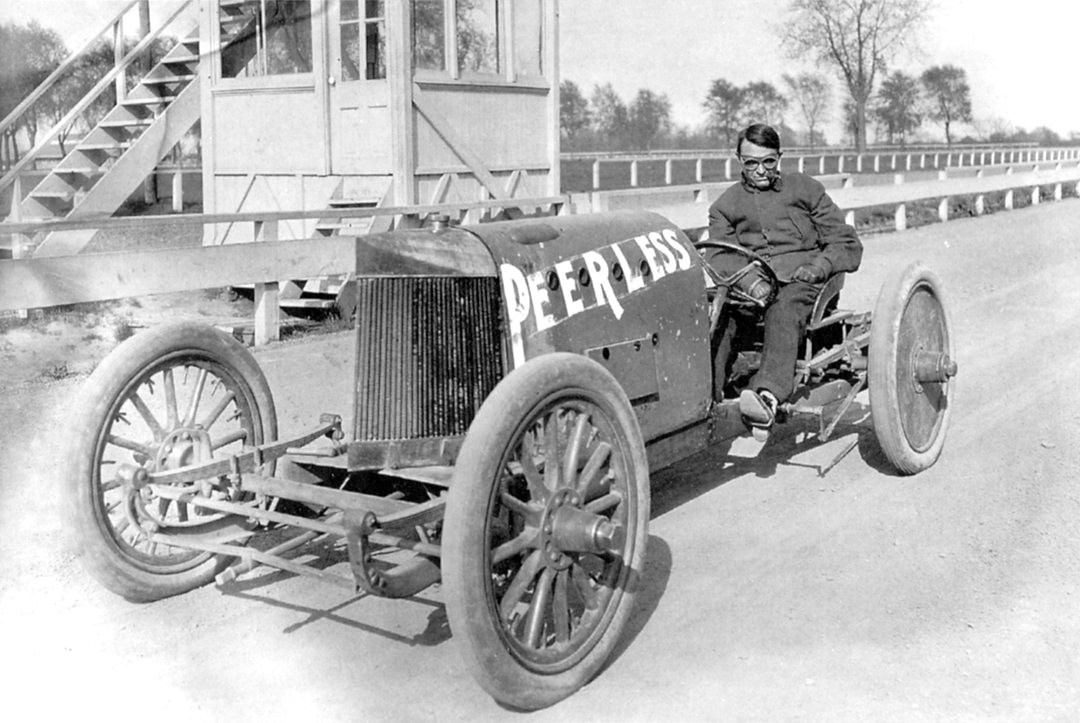

Oldfield’s first recorded auto-related visit to Los Angeles came in November 1903 at Agricultural Park. He staged a 3-day event consisting of speed record attempts, match races, and exhibitions aboard the Winton Bullet. An accomplished bicycle racer, Oldfield earned the respect of early industry pioneers such as Henry Ford, Alexander Winton, and others with his ability to control unwieldy machines at inordinate speeds with uncanny skills that could not be taught—because there was no precedent.

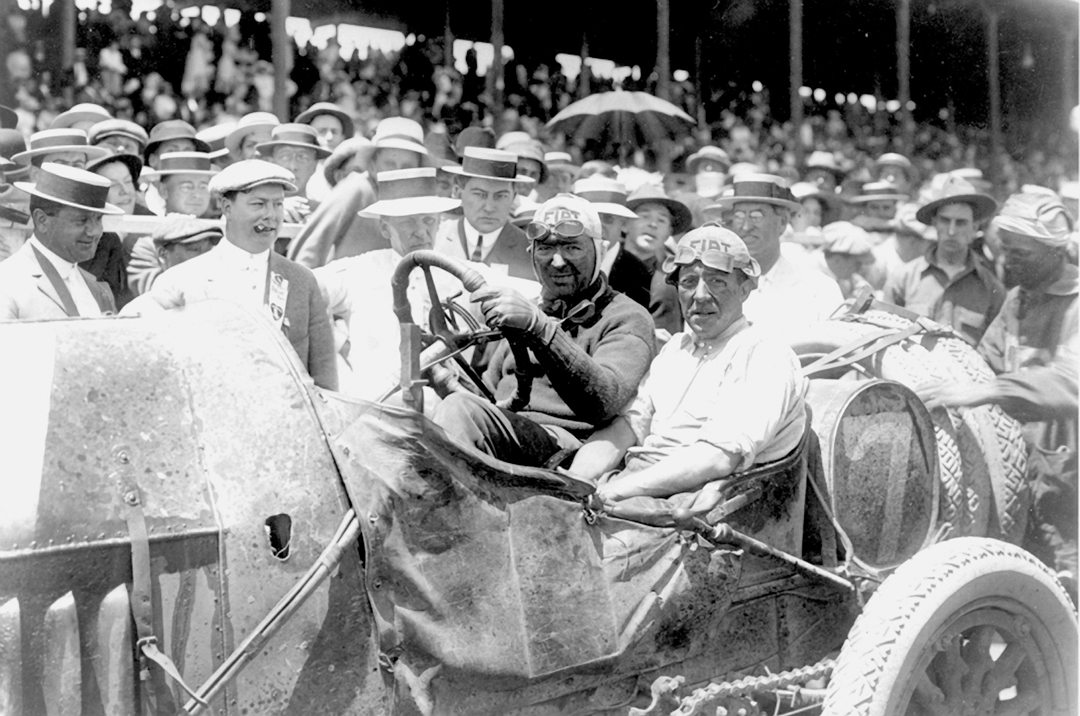

Trailblazers rarely get the credit they deserve. Often, they clear the path for others to follow and exploit for fame and fortune. To some extent, the same can be said of Barney Oldfield. He came at a time when the sport of auto racing was at best described as fledgling. He was a barnstormer, a boisterous shill for whoever would keep him supplied with cigars, whiskey, and cars. He was the first to pilot an automobile over a mile a minute and the first to record a 100-mph lap at Indianapolis. With promoter William Pickens, Oldfield traveled the county fair circuit taking on all comers and staging dramatic come-from-behind victories to the thrilling delight of spectators who rarely had even seen an automobile.

His style did not, however, translate well to the professional racing circuit. Within a few years, auto racing had established rules, points, and a championship schedule. Oldfield often participated at the behest of race organizers and just as often found himself at odds with race officials. Nonetheless, he managed to make a very good showing for himself during many sanctioned events and was always a fan favorite.

Contemporaries Ralph DePalma, Eddie Pullen, and Earl Cooper had groomed themselves as professional drivers and certainly benefited from Oldfield’s presence. More often than not, they also bested him in head-to-head competition. However, Oldfield tended to win the battle of headlines both before and after events.

Oldfield competed in many Los Angeles events and eventually took up residence there. Tracing his multiple race sites allows for a grand tour of this area’s growth. Agricultural Park, once the annual site of Fiesta Days activities and Los Angeles County fairs, gave way to the Los Angeles Coliseum. Oldfield was as regular a competitor as any at Ascot Park’s mile dirt oval in East Los Angeles, on the first all-wooden speedway (The Motordrome) at Marina del Rey, and on the real roads of Santa Monica.

His list of sanctioned wins is short. He won the Venice Road Race on Saint Patrick’s Day, 1915, his only recognized championship victory, but he placed 2nd at Corona and Santa Monica in 1914. He won the grueling LA-to-Phoenix road race in March that same year and was duly crowned “Master Driver of the World” for his efforts.

Barney Oldfield existed in a world without the Internet, television, or even radio, yet managed to become a household name and was readily recognized everywhere he traveled. Los Angeles and Oldfield exploited one another with mutually beneficial results. The Los Angeles County population went from 170,000 to 936,000 between 1900 and 1920, Oldfield’s heyday. The city and surrounding area grew, expanded, and developed in tandem with the automobile. Oldfield had simultaneously been a key instrument in the marketing of both.

Think of Babe Ruth. You can picture the robust man, swinging a bat, waddling around the bases, his round face smiling in an old-fashioned cap. Oldfield was all that and more. Except that you can’t picture him, can you? Moving pictures barely existed in his time. Radio was years away. Oldfield was larger in the American lexicon than Ruth, preceded Ruth by a couple of decades, and set the tone for what helped make Ruth’s persona possible. That’s what trailblazers do.

Tracing Oldfield’s steps in Los Angeles is akin to tracing the development of Los Angeles itself. While the race sites themselves are long gone, the locations remain. Many exist today as common thoroughfares with travelers blissfully unaware of why a road goes this particular direction or that, let alone of how famous the road once was. Fair enough, history is like that.

Barney Oldfield is buried at Holy Cross in Culver City, California, under an unpretentious marker.