When taking a first look at the subject car for a Profile feature the first thing that comes to mind is where is the story behind this car? First, I’ll start with the name of the car—obvious, yes? Not so, what truly is the name of this car? Some say it’s the BMW-March GTP car, others say it’s the March 86G BMW GTP car. I’ve decided to use the name on the promotional material supplied in period by BMW North America—the 1986 BMW GTP car. Second, was it just a “happy accident” that March and BMW came together to produce this car? The story of this car took me on an unexpected journey, which I trust you’ll find as fascinating as I did.

Origin of the Engine Designer

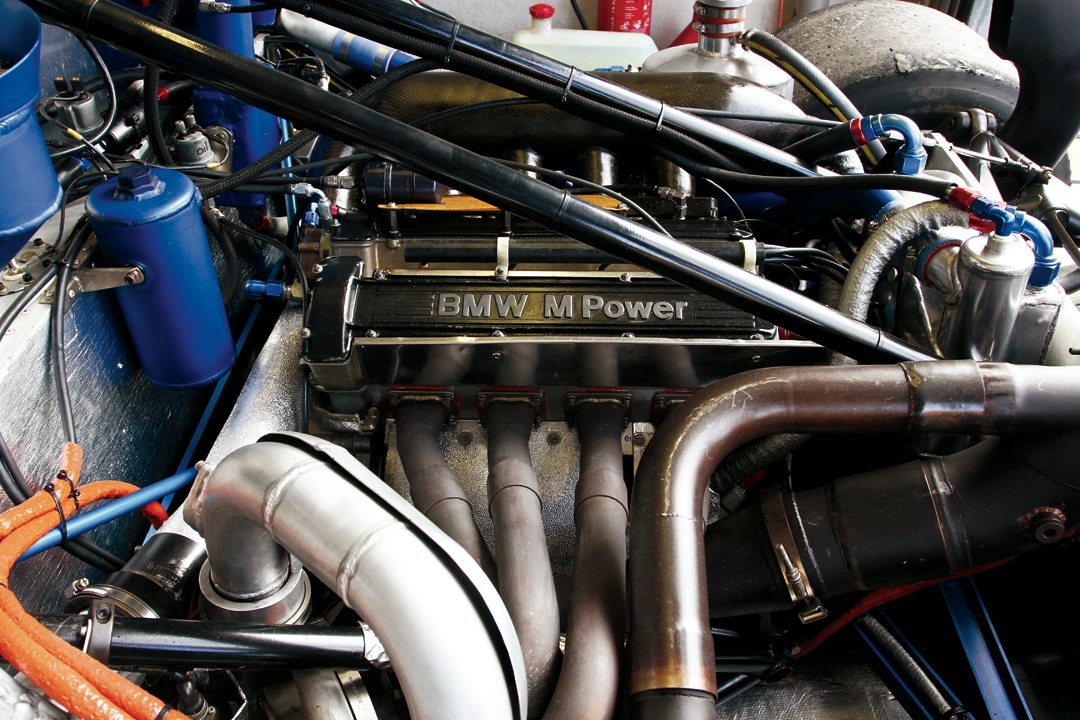

The heart and soul of this GTP car is the BMW M12/14 turbocharged, inline-four engine, capable of producing more than 1,400 hp. The origin of this power unit can be exactly dated to May 22, 1907, birthdate of its designer Baron Alex von Falkenhausen. Born in Munich, Germany, it was first thought the young Alex would follow the family tradition and join the military. However, it was his love of motorcycles that took him in another direction. At just 17 years of age, his first success was on a DKW motorbike as runner-up in a local hillclimb event. While studying wasn’t his forté, engineering was, particularly engine design. After leaving school, he worked as a trainee mechanic for a local company. A couple of years later he knew enough to qualify to attend the Munich Technical University specializing in motor vehicles and aero engines. His professor at University was Willy Messerschmitt, founder of Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, the aircraft company at Augsburg. It was thought he might join this company, but he was under a driving contract from the Bayerische Motoren Werke, more commonly known as BMW. From 1934 to the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Alex von Falkenhausen raced and designed BMW motorbikes. He notably worked first on introducing telescopic front forks to his experimental motorbike, the R5, and later added rear suspension that helped him win a great haul of gold medals for various speed, hillclimb and endurance events in 1936 and 1937.

Throughout the war years, like many British car companies, the German car works were geared to produce military vehicles. Von Falkenhausen was given a brief for two projects, first to design a military motorcycle combination with a monocoque sidecar. The second was to design a one-person armored vehicle. Following the German surrender and cessation of hostilities, von Falkenhausen set up his own company to tune BMW 328 cars, going on to produce his own racing cars fitted with 328 engines. At first, he thought it a good idea to call the cars Al-Fas (“Al” from his first name Alex and “Fa” from his surname Falkenhausen), but it was soon obvious he wasn’t going to get away with it! So, the new company became Alex von Falkenhausen Munich (although some journals use Motorenbau instead) simply known as AFM. While von Falkenhausen raced the cars himself, he recruited a number of other German drivers to his team, most notably Manfred von Brauchitsch and Hans Stuck Sr. It was Stuck who gave the new Formula Two spec AFM-1 car its first success with a 3rd place at the Grenzlandring circuit in the Lower Rhine area of Germany. The car was quite successful later, going on to beat the Ferraris of Ascari and Fangio at Monza. While the new cars couldn’t initially compete in the new F1 World Championship, they were entered when the new championship ran to F2 regulations in 1952 and 1953. By 1954, Formula One had new regulations that once again precluded the AFM cars. It soon became obvious that it was going to be a tough fight to continue as an entrepreneur, but by this time von Falkenhausen had been offered a place back at BMW as a driver and head of the motorcycle racing program—later he became head of engine development.

The “New Class” Engine

Baron Alex von Falkenhausen won many rallies in France, Austria and Germany, ably assisted by his navigator wife, “Kitty”—the Baroness Katharina. A good number of these victories were in his trusty 16-year-old BMW 328, but in 1956 he changed to a BMW 502. By 1961, work was going apace on a new four-cylinder engine. While BMW wanted him to produce a 1300-cc power unit, von Falkenhausen steered them toward a more versatile 1500-cc unit with the capability of being bored to 1800-cc and 2000-cc. Time has proved this initial decision to be a remarkable stroke of genius, as the engine has been the mainstay of the BMW motor company for many, many years.

The engine was first used in the BMW 1500 and was exceptionally good in racing cars. Von Falkenhausen himself won the Eberbach hillclimb and a gold medal in the Munich-Vienna-Budapest Rally in a BMW 1800 TI/SA. Now, in his late 50s, it was time for the Baron to hang up his race suit, helmet and goggles, but a new member of the family was to step into his shoes, son-in-law Dieter Quester. Although competitive motorsport was off the agenda, an attempt at record breaking wasn’t. A two-liter version of the new engine, now with four valves per cylinder, was fitted into the back of a Braham BT7. The car was taken to the Hockenheimring and the 59-year-old Baron was in the cockpit ready to take on the challenge at the 500 meters and ¼-mile distances. Later, the car was used as a works racing Formula Two car in the hands of Hubert Hahne.

BMW in Motorsport

Following his retirement from competition driving, von Falkenhausen became head of BMW’s motorsport department. He was well qualified, knowing the challenges the position would present after experiences at his own AFM. He’d had great discussions with the board at BMW convincing them of the significance of the marque participating in various racing and rallying events. A term well used in the motor industry shows success on the track will lead to successful sales in the showroom. The European Touring Car Championship (ETCC) was the first goal with the BMW 1800 TISA and victory at the prestigious Spa 24 Hours was the first along the way with Belgian drivers Pascal Ickx and Gérard Langlois van Ophem. Further success wasn’t too far ahead with Hubert Hahne winning the 1966 Div. 3 in a BMW 2000Ti and Dieter Quester winning the same division in 1968 and 1969 at the wheel of the BMW 2002. Since then, BMW has continued to build on its rich involvement in sedan and sports car racing over many years.

Photo: BMW Group Archive

However, for 1967, open-wheel racing was the next frontier for the Munich-based marque. BMW tried initially with its own chassis, but moved to Lola to provide type 100 chassis for BMW-sponsored drivers like Hubert Hahne, Jo Siffert and Dieter Quester. Two Lola 102 cars, sometimes referred as F268 cars, (designed by Lola and built by Dornier) were used, initially with the notoriously unreliable Apfelbeck rotary head engine. Using more conventional power the car came good for Hubert Hahne’s 2nd place at the AvD Trophy race. Halfway through the 1969 season BMW debuted its own new F2 chassis, the 269, designed by Len Terry, in which the unfortunate Gerhard Mitter tragically lost his life during practice for the 1969 German GP at the Nürburgring. The BMW cars were immediately withdrawn. In 1970, they returned to F2 once again with a new Len Terry 270 chassis for the regular driver, plus newcomer Jacky Ickx, to drive. However, while withdrawing from producing its own chassis and becoming an engine supplier only, BMW was still successful, winning with Jean-Pierre Jarier in 1973, Patrick Depailler in 1974, Jacques Laffite in 1975, Bruno Giacomelli in 1978 and Marc Surer in 1979—the last two being part of the Polifac March-BMW Junior team.

Photo: BMW Group Archive

BMW in F1

The basis of the BMW engines used for competition and motor racing can be genetically traced back to those first “new class” designs by Alex von Falkenhausen. As time goes by, age takes away certain people and replaces them with others. So, in the case of BMW, the engine design responsibility slowly transferred away from “Baron BMW” to Paul Rosche—who was to become known as “King BMW” and father of the BMW turbo engine. Rosche was a die-hard BMW man and had been with the company from an early age, after leaving university. Indeed, he had input to most of the successful von Falkenhausen engines, which bore Rosche’s signature tuning and modifications. In the early 1980s, Rosche was the Technical Director and had a firm hand on the new design of the F1 BMW turbo engine that was to be used by Bernie Ecclestone’s Brabham team. The 1.5-liter engine fitted with a Kühnle, Kopp & Kausch (KKK) turbochargers was a highly tuned four-cylinder power unit with 16 valves posting an initial output of 800 hp—eventually being designated the M12/13. The Brabham BT50-BMW debuted in the 1982 season with Nelson Piquet and Riccardo Patrese at the wheel. Initially, there were teething problems that blighted progress and tested the relationship of both parties, however, within just 630 days, using two chassis possessing extra power output that was believed to be around 1400 hp, the F1 World Championship was won with Piquet in the dart-shaped Brabham BT52. Success proved difficult to maintain, and although the team had the odd win here and there it was on a downward spiral. Other F1 teams to use the engine from 1982 to 1988 were ATS, Arrows, Benetton and Ligier. It was to power Gerhard Berger to his maiden GP win at the 1986 Mexican GP in the back of his Benetton B186-BMW.

Photo BMW Group Archive

BMW Go IMSA Racing

As we have mentioned before, motor racing success is directly proportionate to an increase in sales, that’s why, financially speaking, many manufacturers have plowed millions into motor sport. The U.S.-based IMSA GTP racing series was one of those that drew good drivers, professional, semi-professional and amateur teams and great cars. It was a stage where David could take on Goliath. Spectators too were drawn to the series and it created great publicity.

BMW first thought of entering in the early 1980s. A time when many of the sports car racing series had upgraded their rules. World Endurance Championship had Group C replace Group 5 as the premier class, just as the U.S. IMSA series replaced GTX with GTP as its premier formula. Looking back on their then recent success in F2, BMW turned to March to produce a chassis under the guidance of Dr. Max Sardou, a highly qualified engineer having qualifications in physics, mechanical engineering, aerodynamics and automotive design. Sardou’s design, known as the 81P or the BMW M1C, had the tell-tale March “lobster claw” front end and incorporated huge venturi tunnels at the rear. In actual fact, the chassis became the prototype for the March “G” series of cars. For their part, BMW used its 3.5-liter, inline six-cylinder naturally aspirated engine to power the new car, giving some 650 hp, which was a little inferior to the Porsche 3-liter engine that gave around 700 hp—as did the Chevy V8. On other occasions, they used a two-liter turbo engine, but the output of that was not much better. However, Paul Rosche was deeply involved with the new time-consuming F1 turbo engine for Brabham, and had no real inclination to develop yet another engine. Prior to shipping to the U.S. the car was tested by Christian Danner at Silverstone, in the UK, with very experienced British driver, David Hobbs, taking on regular racing duties. Hobbs was joined in some races by teammates that included Marc Surer, Vern Schuppan and Hans Stuck Jr. The underpowered car hardly looked capable of podium places, but finished 6th the first and second time out, a lowly 20th next, followed by another encouraging 5th at the 200-mile Mid-Ohio race. In early August, at the one hour Portland race, room for more encouragement came as Hobbs took 4th place. Just prior to the last race of the season, the Road Atlanta 150 miles, BMW announced its withdrawal from GTP—even a planned March 81G-2-BMW for European racing was canned as F1 took the limelight. To many observers, this first foot in the series was a half-hearted attempt by the German manufacturer.

That was it until 1985, when BMW North America felt the time was right to give GTP another chance, though this was to be without any financial support from the parent company based in Munich, Germany. The North American office had, however, seen how Ford and Chevrolet had grown by competing in GTP. Again, March made the chassis—number 7 to be precise, an up-graded 85G with remodelled radiator inlets in the side. It ran in just the one race, the Daytona Three Hours Finale, the last race of the season held in early December. As the car took to the track for the first time it was dubbed “Donald Duck” for its ugly appearance. However, David Hobbs, Davy Jones and John Andretti caused a stir when they qualified the car 2nd on the grid. Power was now from the former Grand Prix 1.5-liter, single turbocharged engine bored out to two liters and tuned by McLaren North America to give an estimated 1,050-hp, but the McLaren race team complained of the fuel BMW was using. It was very corrosive and care had to be taken handling it. After just 30 laps, Hobbs retired the car with gearbox issues—it was classified in 60th place.

The New BMW GTP Challenger

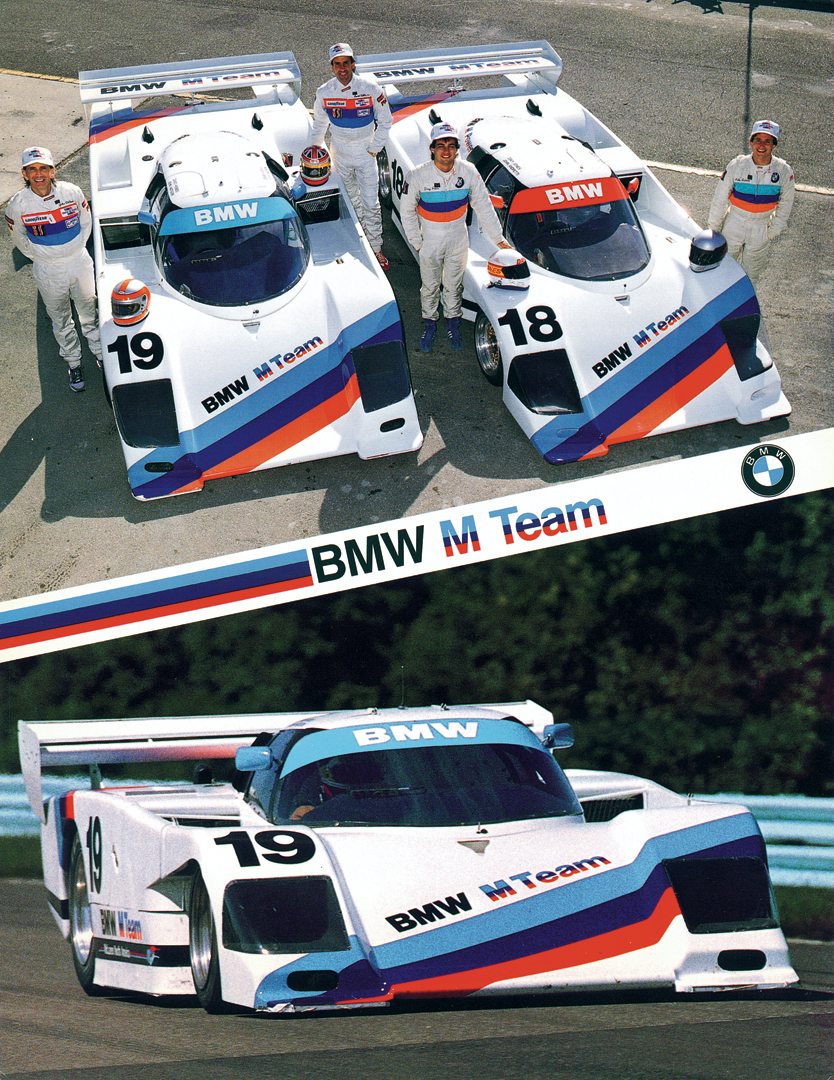

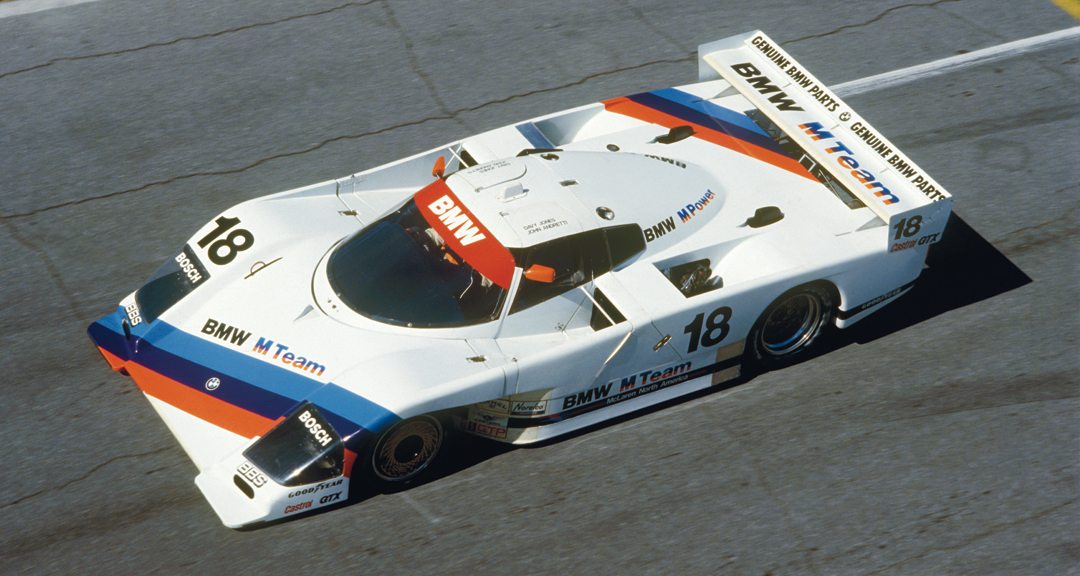

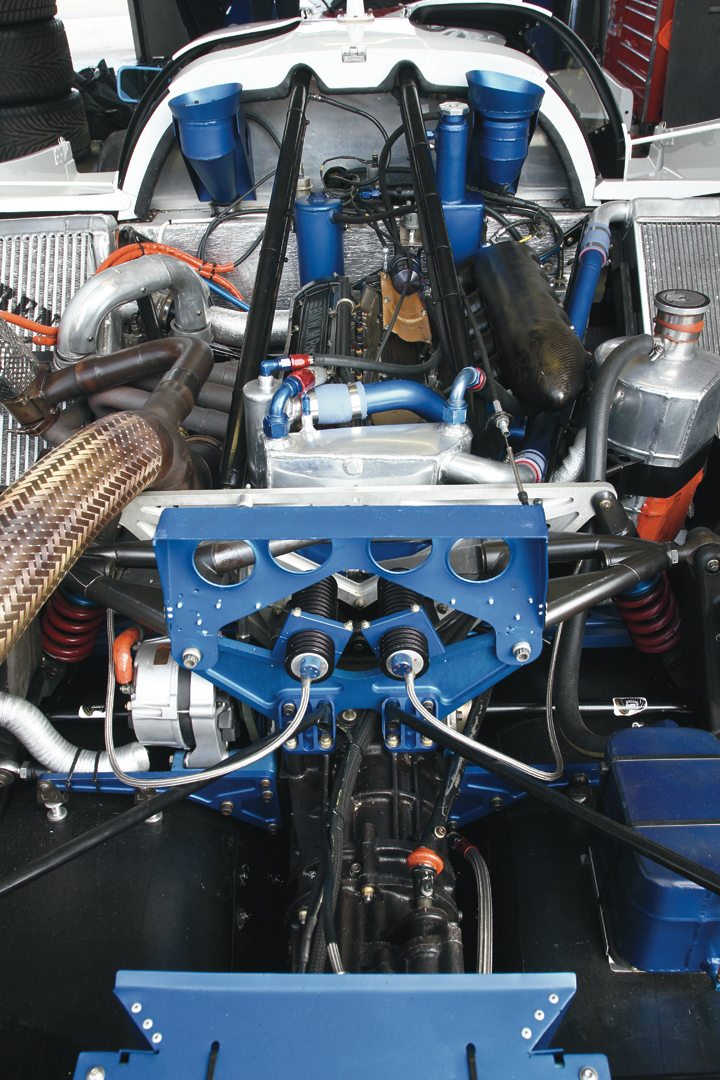

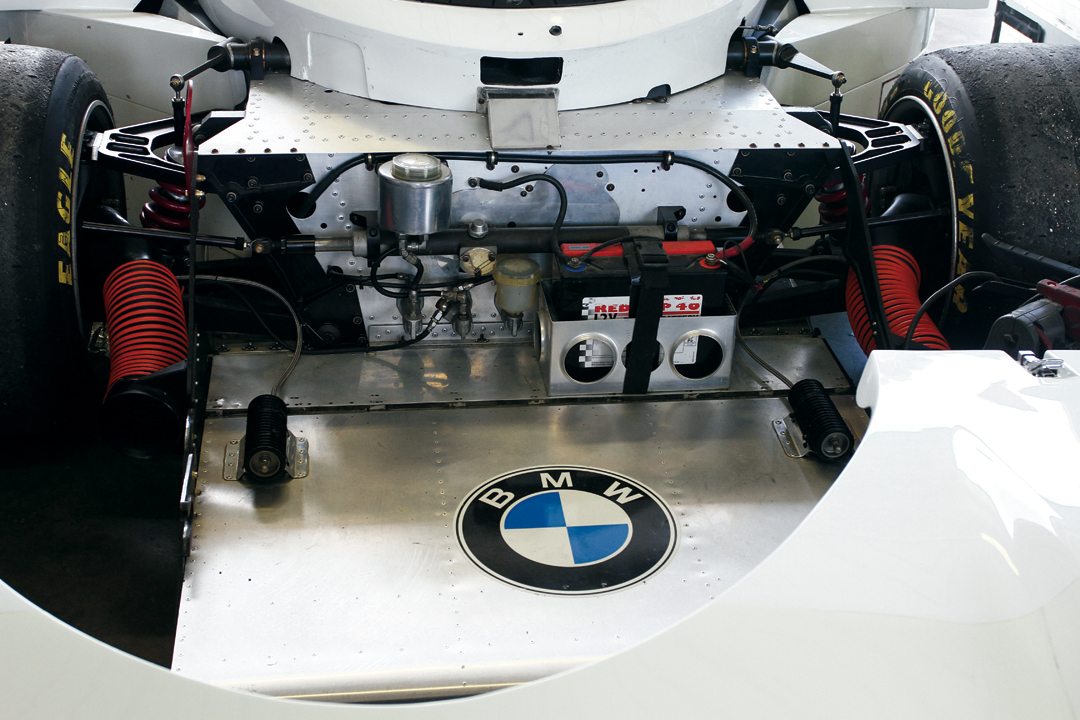

For 1986, a new car to be known as the BMW GTP was built to try and wrestle the stranglehold Porsche seemed to have on the championship after winning 15 of 16 races in 1985. Once again, the Bicester-based, UK constructor March was commissioned to design and build the chassis. Six chassis were built in total—the first to be wholly designed by a Computer Aided Design (CAD) program. BMW/McLaren North America had chassis numbers 86G 1-4, and a further two chassis, numbers 86G 9 and 10 (Nissan too took delivery of a further four, chassis numbers 86G 5-8, that were made to a slightly different specification and sometimes referred to as 86C). The first of the BMW March chassis was delivered in early November 1985, and the rest followed very soon afterward. Construction of the chassis was in line with the thinking of the day, with an aluminum monocoque reinforced where necessary with carbon fiber. BMW designer Manfred Rennen was responsible for the bodywork that was a carbon-fiber and Kevlar composite. The engine was mounted longitudinally on a steel tube subframe. Suspension technology and design was in line with coil damper system with front and rear wishbones similar to March Indycars of the day. Braking was via ventilated discs.

BMW power was to come from upgraded M12/13 former F1 engines, as with the 1985 car, bored out to two liters and modified by McLaren North America, power was boosted using a single turbocharger by Garrett Air Research and transferred to the wheels through a March 5-speed gearbox. In qualifying trim, the engine was said to have pushed out 1400-hp, and was capable of speeds around 220 mph. Problematic turbo lag had been addressed; or rather drivers became now more au fait with it not to cause an issue. Talking of drivers, as is the German norm, there was a senior team of David Hobbs and John Watson, and a junior team of Davy Jones and John Andretti. For the first round of the series two more drivers were taken on, Bobby Rahal to join the senior team and Dieter Quester to run with the juniors.

However, there were dramas from the outset. Fire completely destroyed one of the first chassis—believed to be caused by the heat of the turbo igniting the rear bodywork. In another, Bobby Rahal had a serious crash in practice when the rear bodywork delaminated and tore away, in no time the car was airborne. Thankfully, Rahal escaped unhurt, but that was another chassis gone—improper fastening of the bodywork latches were found to be the problem.

Chassis 3

Our profile car, Chassis 3, was part of the second consignment of chassis produced by March, in the UK, and freighted to the U.S. in late December 1985/early January 1986. Following the team’s withdrawal from the opening race at Daytona, the first race the car entered was the Löwenbräu Grand Prix of Miami, on the new 1.87-mile Bicentennial Park street circuit, driven by the seniors, Hobbs and Watson. As expected, the Porsche 962s had dominated the Daytona podium with the Al Holbert, Derek Bell and Al Unser Jr. car winning. During qualifying at Miami, chassis 3 took 11th spot on the grid, with a time of 1min 17.321secs, five grid slots ahead of its sister car. Hobbs and Watson made good progress to finish in 9th, while the junior team retired after Jones had an accident upon leaving the pits with just 30 minutes gone.

The next venue for the chassis was the Road Atlanta road course, in Georgia, situated in a quite tranquil setting that disguised the inherent dangers of the undulating circuit. Watson and Hobbs were once again the drivers. The team was optimistic of a great race after claiming 8th place on the grid. It is said the norm was to change engines between qualifying and racing as in qualifying the boost was turned up to maximum, while in race trim it was run slightly lower. As the car prepared to cross the line for the completion of the first lap fire engulfed the rear engine cover. The BMW had become a barbeque once again. John Watson was at the wheel and had to be extricated and helped to safety by fellow Brit Derek Bell and Jaguar’s Bob Tullius who’d run to assist the marshals. This retirement forced a major rethink, and Nigel Stroud came in to try and steady this very rocky ship.

Photo: BMW Group Archive

Chassis 3 took on Stroud’s modifications as described above and was next seen on track at Watkins Glen for the first of two visits during the season. This time the car was in the hands of the junior team, Jones and Andretti. The young chargers claimed 10th place on the grid and finished a very creditable 5th to save the embarrassed blushes of the BMW hierarchy.

Spurred on by this success, Portland, the next venue for the IMSA cars, beckoned and was looked forward to. From 12th place on the grid, hindered by a qualifying accident, the Andretti/Jones combination knew their objective was to push to the front. Unfortunately, the motor racing gods declared enough was enough and John Andretti steered the car off the road and into retirement, denying Davy Jones a chance behind the wheel.

It was nearly three months before Chassis 3 raced in anger again. It was the senior squad of Watson and Hobbs back in harness with the car taking 5th in qualifying on the bumpy streets of Columbus, for the Ford Dealer’s 500 race—a tremendous effort given the rain-affected sessions. Hobbs took the first stint and had a great dice with the Jaguar of Bob Tullius fighting over 6th place with Hobbs in front for most of the stint. John Watson took over the driving duty after the pit-stop and set about maintaining or bettering their race position. After a few laps, he was in 4th place and chasing down the leaders. Using the power and torque of the BMW turbo engine, which was now really “on song,” Watson was soon up to 3rd and looking to establish a podium position. An uncharacteristic mistake by Watson saw the car spin out at the Town Street Bridge/Civic Center Drive corner. He regained control, but lost a couple of places. Ill fate struck again, when the car retired from the race on lap 79.

Photo: BMW Group Archive

The last race of the season was the finale, the Eastern Airlines GP at Daytona. Al Holbert had been crowned driver champion and Ford was the manufacturer champion for 1986. Notice had already been given that this may be the last race for the BMW team, but perhaps a good performance could change the hearts and minds of those responsible for racing strategy at the team headquarters in Munich. Qualifying went well with an amazing 2nd place putting the car in a great position for the senior squad to emulate the junior team success at Watkins Glenn just a couple of races earlier. Watson took the lead at the start, but at the end of the first lap the power of polesitter Sarel van der Merwe’s V6 turbo Chevrolet Corvette took command and sped past on the banking. During the opening laps the story was about these two arguing the lead as the laps counted down, with Watson catching and passing on the slower parts of the circuit. As the race progressed, those gremlins that had blighted the whole campaign surfaced again and the car dropped down the order finishing 8th at the flag. From there on Chassis 3 was put into storage, as the decision to withdraw from racing was taken.

The car was ultimately released by BMW and sold to a private concern for restoration, remaining in the U.S. until the current owner, Dr. Peter Garrod, purchased the car to compete in historic Group C racing in Europe.

Driving BMW GTP Chassis 3

We’re at Donington Park Racing Circuit, in the East Midlands of England, for this unique test. What’s so special about this, you may ask? Well, this BMW GTP car only arrived in the UK from the USA a couple of weeks before, what’s more it will be the first time this car has ever turned a wheel on UK soil—quite a moment then? The month of August has been one of the wettest on record, but thankfully although very overcast we’ve had no rain on this early September day. The track is dry, humidity at 59 percent, visibility very good, a slight fresh west-north-westerly wind and temperature of around 53°F. The Alpine white car emblazoned with the customary diagonal blue, violet and red tricolor stripes with the “M Team” logo (motorsport livery of the Bayerische Motoren Werke division) looks extremely sleek and dynamic as it sits on the concrete pit apron ready for action. A throng of mechanics and team personnel from neighboring pit garages gather around in wonder and awe of its presence.

Photo: Dan R. Boyd

To business though; entering the cabin of the car is much the same as that of similar GTP/Group C cars, however, one has to be a little more agile than usual, worming and wriggling to get comfortably seated and in the driving position. It’s at this point you begin to understand how fit drivers had to be—even in the mid 1980s—to contend with quick driver changes.

Now seated, the carbon-fiber dash curves in front with dials, switches, sockets, lights and digital readouts all well marked in true German methodical style, leaving the driver well and immediately informed of the purpose of each. While the driver can keep account of various pressures and temperatures during his driving stint, there are two main displays. First, the biggest of the dials is the rev counter, centrally placed and ideally situated with clear pronounced markings for the driver to glance at when at speed. Second, to the far right, are three bold orange warning lights one above the other. When illuminated the driver will be aware of dangerous issues with either the fuel, oil or water. Unlike modern steering wheels the Momo racing wheel is devoid of any instruments or buttons and is there for a singular purpose.

The button we first look for is situated to the bottom far left of the dashboard—the starter. As it is depressed the already warmed engine bursts into life. However, it’s not with the anticipated roar, but more like a purposeful purr. Remember, it’s the turbo that will offer the blast of power once we’re on track, up to speed and within the correct rev range. It’s with great trepidation and sense of occasion that the clutch is depressed, first gear selected and engaged. Upon releasing the clutch we’re off and running, albeit slowly down the pit lane toward the pit marshal who waves us inexorably on toward the circuit entrance. We join the circuit tarmac and we’re in second gear building the revs as we negotiate Red Gate corner, and downhill through the Hollywood and Craner Curves sector we move through third to fourth gear as we approach the lowest point of the circuit. The car, although very light, is stable through these initial bends, no oversteer or understeer. Taking the right-hand Old Hairpin we’re down to second, hitting the correct apex to put a foot down to accelerate through two shallow left bends, the first under Starkey’s Bridge and the second Schwantz Curve to the 90-degree McLeans right-hand corner. Through this section with the revs hitting around 5,500–6,000 rpm the car begins to really fly—there’s a punch in the back as the turbo engages. Although expected, this punch of power surprises as there is transitory delay between pressing the accelerator, the revs building and the might of the turbo engaging.

Back into second gear as we negotiate McLeans we have still to keep the revs up, as the engine is capable of dying. Exiting the corner we’re back “on it” through to fourth as we go down and then up toward the double apex right Coppice sector. Top of mind, at this stage, is getting the correct exit, once again to put the full power down on the fastest section of the circuit that is the straight running alongside the Exhibition Centre. We’re on the full Grand Prix circuit today, so it’s a left and right chicane onto the straight down to Melbourne Hairpin. Exiting the second apex of Coppice Corner it is becoming apparent that this engine prefers high revs in a low gear rather than moving through the gearshift to a higher gear. High engine revs engages, or keeps the turbo engaged, which in turn keeps the power on. Although the boost is turned down, we can appreciate the power of the car—goodness knows how fast it would be at full boost! Braking hard at the 3-2-1 markers for the left and down to second it’s quickly up to third downhill toward the Melbourne Hairpin, exiting the tight 180-degree turn we’re back into first gear ascending back up through to second and third then back down to first gear to take another 180-degree corner, Goddards, then left onto the Wheatcroft Straight to complete the lap, building through the gears to Redgate.

The general feeling of the test is that this is a finely balanced, powerful car; indeed it drives through corners as though it were “on rails.” Its idiosyncrasy lies within the turbo, with the boost turned down it comes in around 5,500, turned up it no doubt will come in a lot earlier, around 3,500rpm. Turbo boost lag is another foible to understand, exactly knowing when the power will kick in is paramount for competition purposes. The remarkable thing is how well balanced and light the car appears, although one small problem is a slight wobble when the power is lifted—something for the mechanics to work on? The car was taken to a maximum of 8,500 rpm today on low boost, as mentioned earlier, but there’s no doubting the power available to the driver. Driving to keep the turbo engaged, which means keeping the revs over 5,500 rpm, is key. Today, under 5,500 rpm the car was only as powerful as a Mini. All in all, at just over 800 kilograms, it feels like an oversized go kart, it can be drifted in and out of corners, it’s very fast along the straight and simply a beautifully handling car. Despite the problems in period, I feel BMW really had something to show the world with this car. Indeed, David Hobbs is reported to have said, “This is the fastest car I’ve ever driven.” Speaking to a number of drivers of the day about the BMW challenge most seem to agree with me, it was a case of unfinished business!

SPECIFICATIONS

Constructor: BMW North America / McLaren North America

Chassis: March 86G aluminum honeycomb monocoque BodyCarbon fiber / Kevlar composite

Engine: BMW M12/14 2000-cc 4-inline water-cooled, turbocharged

Turbo: Single Garrett AiResearch turbocharger

Block: Iron linerless, aluminum head, 5 main bearings

Crankshaft: Steel

Con Rods: Titanium

Pistons:Mahle light alloy with Goetze rings

Camshaft: DOHC, gear-driven, 4 valves per cylinder, single-plug

Engine management: Bosch Motronic

Engine weight: 160 kilograms

Suspension: Coil/damper – Front and Rear wishbones

Wheels: BBS rims

Tires: Goodyear

Gearbox: March 86T / 5-speed

Wheelbase: 2685 millimeters

Front track: 1565 millimeters

Rear track: 1539 millimeters

Weight: 850 kilograms

RESOURCES

Bibliography

Inside IMSA’s Legendary GTP Race Cars, by J.A. Martin and Michael J. Fisher

Endurance Racing 1982 – 1991, by Ian Briggs

The Story of March – Four Guys and a Telephone, by Mike Lawrence

Grand Prix Who’s Who, by Steve Small

Generation Turbo by Bernard Asset and Johnny Rives

IMSA Yearbook 1986

Periodicals: Autosport, Motor Sport, AutoWeek and Bimmer

1986 BMW M Sport GTP Press kit

Sincere thanks: To Dr. Peter Garrod for his time and the use of his car To Phil Stott Motorsport for transporting the car to

Donington Park

To Donington Park Circuit and staff for their help

To BMW Group Archive for all help and assistance with providing period photographs and information