The Lancia Fulvia

Lancia was never short of talented engineers. Consider just Vincenzo himself, Vittorio Jano and, later in the 1950s and ’60s, Antonia Fessia.

Vincenzo had established the company as a forward-thinking quality constructor of motorcars and commercial vehicles, and ex-Alfa genius engineer Jano had developed this concept, in particular in the sphere of sporting vehicles, while Fessia applied advanced thinking as the solution to relatively mundane problems.

As early as 1947, the latter had masterminded the appearance at the Turin Show of a front-wheel-drive chassis powered by an 1100-cc flat-four engine. This eventually metamorphosed into Lancia’s Flavia Sedan, but the Torinese company also introduced and developed a small car called the Appia that continued carrying the baton, initiated pre-war, with the Aprilia. It had a narrow-angle V4 engine of just above one liter and, through the 1950s, was Lancia’s “entry-level’ product. Despite several subsequent updates, by the early years of the 1960s it was beginning to show its age, so company owner Carlo Pesenti agreed to the development of a replacement, and Professor Fessia was only too happy to oblige.

The car he designed was given the title Fulvia and, typically, indulged some avant-garde features for the period. Announced at the Geneva Show in March 1963, the first manifestation of the model was a boxy little berlina which, from spring ’63, began to be turned out of Lancia’s new factory at Chivasso, a few kilometers east of Turin. The latter was subsequently occupied by Maggiora, who built all the integrale Evo models there, along with the Lancia Kappa coupe and ironically (see later) the Fiat Barchetta.

Fessia’s originality was clearly displayed by the little Berlina’s 1091-cc, 13-degree staggered-bore V4, which was canted over at 45 degrees and drove the front wheels, but the lack of cubes meant that power output was never going to be enough to endow a 1040-kilogram car with a lot of performance. For the unit’s size, however, 58 hp was a good starting point. The later addition of more and larger carburetors helped push power up to 71 hp and nudged sales in the right direction so that 80,000 Fulvias in total were sold in five years.

One result of the relative success of the Berlinas was the whetting of customers’ appetites for something a little bit more special so, in 1965, Lancia obliged by dishing up the Fulvia coupe, which featured in-house styling by Pietro Castagnero and his team. With an elegant and airy cockpit area, probably the best accolade that the shape could receive is that it remained fundamentally the same for the whole of the model’s 11-year life.

Despite their ability to be innovative, Lancia introduced the new model with nothing more than a modest capacity rise of the V4 power unit, to 1216-cc delivering 80 hp. Top speed though was a genuine 100 mph, so the stylists obviously knew what they were doing. They had produced a car with an exceptionally low, for the period, Cx figure of 0.39. This was in a time when the generally accepted way of getting a vehicle through the air faster was to increase the capacity, and thus power, of the engine. The coupe’s suspension was by unequal arms and a transverse leaf spring at the front, while the rear consisted of a dead tubular rear axle supported by semi-elliptic leaf springs.

In 1966, a sportier version was announced and this adopted the famous HF—HiFi—appellation from Cesare Fiorio’s Lancia competitions department, HF Corse. Power was up to 88 bhp and inevitably a competition version had been developed, which made its debut on the 1965 Tour de Corse. By early 1966 a Coupe HF won the Rallye dei Fiori, later to become the San Remo Rally, and in 1967 a full-scale assault was mounted on the top rallies of the world, an activity that continued unabated until 1974 when the Stratos took over.

In the meantime, the ability of the chassis to accept more power had led to an increase in capacity to 1298-cc for 1967. Thus powered, the Fulvia Coupe Rallye 1.3S was announced.

I have been able to sample and compare three different versions of these charismatic little coupes spanning a six-year period of Fulvia production. They were not tried in any particular order, but for the purposes of this story I will present them in chronological order.

Fulvia Rallye 1.3S

First impression is of their shape; a light, glassy cockpit on a short-wheelbase version of the Sedan’s chassis. It simply works. Probably best viewed in profile, the Coupe’s proportions are just right except perhaps the nose treatment seems to be a little heavy, perhaps not helped by the habit of all Fulvia Coupes to sit slightly nose down.

The blue-grey livery of our test car is typical of Lancia’s thinking at the time as the technical side of the business consisted of a bunch of immensely talented engineers trying to produce the best machine they could devise for the job, so what was the point in turning them out in fancy colors? As opposed to today’s obsession with grey cars.

This policy, or perhaps this would better be described as custom, resulted in the cars generally being purchased by professional people. As much as anything, they were the only ones who could afford them new. All that engineering integrity and expertise in production led to a hefty price tag by the time the cars arrived in showrooms.

So, having salivated over the car’s good looks it’s time to open one of those wide doors and realize immediately that the expertise carried over to the model’s interior. Here, there was no skimping, with well-designed leather-covered seats and a neatly shaped wood-faced dashboard, with built-in grab-handle for the passenger and proper instrumentation consisting of speed and rev counters of large, equal, size. Between them are complementary fuel, oil pressure and temperature gauges.

However, all of this is overshadowed by the seemingly vast wood-rim steering wheel, and I had initial misgivings about the long, wand-like gear lever protruding up from low down out of the front bulkhead. Ready to run you down the road is a 1298-cc V4 unit rated at 90 hp at 6200 rpm. Fuel is fed by two horizontal Solex carbs and the power is transmitted to the front wheels by a four-speed gearbox. I admit that my preconceived judgment of the little coupe was somewhat clouded having previously tried the full-on 1.6 HF, but this smaller-engined car turned out to be a completely different animal.

While slotting the gear-lever into first and waiting to move away I had visions of hopeless early Mini gearboxes (I endured three years hard labor on those back in the ’60s), where selection always appeared to be more by luck than judgment, but it very quickly became clear that the Fulvia was on a different plane. The length of the lever meant that movement at its tip was, perhaps, magnified slightly, but changing gear was like flicking a switch, albeit a long one. Light clutch pressure and caressing the wand was enough to do the trick and, for 1300-cc, 60 mph comes up in under 11 seconds. It’ll go on to 106 mph given a clear enough piece of road.

Jerry Titus, in the April 1967 issue of Sports Car Graphic said, after a hard-driving 150 miles “there were no flaws…neither the coupe nor its pilot were even breathing hard……….we wound up very fond of the little Fulvia.”

The point is, this is not a fast car, but one that can move across country very quickly. The handling is delightful with a firm but comfortable ride except over short undulations. It will definitely understeer, especially if provoked, but essentially it’s light to handle and well-balanced. I could well understand why the Fanalone I had tested previously had a smaller leather-rim steering wheel as manipulating the standard, oh-so-slim, wood wheel initially felt rather like steering a ship. To replace it though would spoil the originality of the car and destroy the chance of getting to know the car as designed, which clearly demonstrated the almost tool-room like standards of construction that Lancia strived to achieve.

In short, this was a jewel; watch-like in its precision and clothed in that slim-pillared modern body that does not look out of place today. Balanced and quick, it is easy to understand why the cars racked up an outstanding rally record.

And talk of rallies turns our thoughts to the ultimate Fulvia.

Fulvia Rallye 1.6HF

This is the one that Lancia aficionados go all gooey about. “Top of the range, sir” as the tight-trousered contemporary salesman would announce today. It is also very rare, only 1,258 of this type were ever built. This example is an original car, having had five owners.

The point of the car can be spotted immediately and no, the black plastic add-on wheelarches weren’t bought at a motor-factor’s on a Sunday morning and fitted at home, Rallye 1.6HFs came with them as standard from the factory, fitted to allow FISA motorsport homologation of wider wheels and tires. This suggestion of purpose and intent gives the game away even before you sample the driving experience, as these cars were built purely to allow Lancia Corse to go rallying and win outright, instead of just picking up class placings as previously.

Gone was the small 1300-cc engine, replaced with an even narrower-angled 1584-cc V4 fed by two 42-mm Solex carburetors. Now, you had 115 hp to play with and the works cars would have had more—but that’s not all.

Lift the bonnet. It might as well be made of paper it’s so light, and the same goes for the trunk lid. Inside, the theme continues with bucket seats that make you feel like Sandro Munari and, looking down, you contemplate the purposeful lever that controls the five-speed gearbox that, on the first 1000 1.6HFs, was created by bolting the fifth speed housing to the side of the four-speed unit, first being selected as a dog-leg.

There is a handsome, reduced diameter from normal, leather-rim steering wheel, but it still has that period slim rim, which feels so delicate in your hands and has you scrabbling through the long-forgotten contents of drawers at home, trying to find those backless driving gloves you used to use.

This is the famed “Fanalone” Fulvia, so named because of its enormous inner headlamps, crucial for rallying. Settle in, turn the key and as soon as the engine fires it sounds like a bunch of angry wasps trapped in a tin. It is incredibly eager to deliver but, you must drive gently at first to allow the gearbox oil to warm up. Then you can ease the throttle further to the floor and the steering becomes more fluid and the whole car starts to beg to be driven appropriately.

Dunlop discs all around deal with the stopping situation, but it is through the application of a curiously mushy brake pedal, which initially raises questions such as “Is it actually going to stop?” but which works very well once you become accustomed.

Like a big kart, the car goes exactly where you want it to. You point it and with poise and precision it responds to your every whim. With typically period low gearing, which would have been suitable for rallying, it can become pretty noisy within that elegant glass house, especially at motorway speeds.

This car was never intended as a high-speed cruiser, of course, and its gear ratios seem ideally suited to squirt the car rapidly from 50-ish to 80-ish mph, easily leaving behind frustrated drivers of modern vehicles who never expected a 40-year-old car to have the dynamic abilities of this little jewel.

Much more at home on the twisty bits, here it can be really enjoyed, although over-exuberance with the revs will be curtailed by the manually adjustable rev limiter, which consists of a second, red, pointer needle on the face of the rev counter that can be set to any desired figure. You can feel the same life-blood coursing through the veins of this extremely potent coupe, just as in the later Delta Integrale HF from the same stable. The only difference is 25 years.

Fulvia 3

This is, in fact, a Series 2 car. Confused? Well, Lancia actually never officially created an S3, despite the car’s title.

The takeover of Lancia by Fiat in 1969 did not immediately result in any great changes, but eventually the Fulvia range was rationalized and the “3” appellation stems from the model being given a makeover with items such as a more up-to-date steering wheel and a wooden gear lever knob. White instruments identify this as a “3” while, from the start of Lancia’s second series, all models had enjoyed an upgrade to a five-speed gearbox.

Suspension settings were slightly raised and the design of the wheels reflected then-current tastes. New minimum lamp-to-road dimensions had been introduced in some countries, as part of the fashion for increased vehicle safety homologation rules and so, in particular for the UK market, the outer headlamps were raised as part of a front-end revamp, thus altering the looks of the car considerably.

None of this altered the model’s on-the-road dynamics and, with a better heater (it could hardly have been worse…) and the five-speed ’box, the car was an improvement over its predecessors.

So, here are three different Fulvia Coupes, from three different eras. The one you choose relies entirely on your preferred style of driving, but all will satisfy and, even more, delight you.

And After…

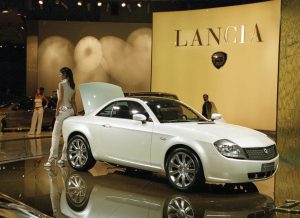

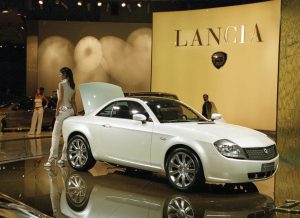

For reasons known only to them, Fiat chose to tantalize the world’s Lancia enthusiasts—and many others—by showing a concept “Fulvietta” at many motor shows during 2003. This gorgeous possibility was based on the floorpan and mechanicals of the then-current Barchetta, so it would have been front-wheel drive with a 1747-cc, twin-cam, four-cylinder engine. Styling was retro Fulvia but exciting, and detailing incorporated all the early 21st century latest technology.

After much speculation and prevarication, the project died despite the concept being briefly resurrected in 2007 on computer as a Spider, based on the then-new Grande Punto platform.

Finally, I have to say thank you to John Whalley for providing these cars and allowing me the enjoyment of a weekend playing at being Sandro Munari.