1966 Eagle-Weslake, Chassis 1G-102

We have had the discussion many times before…What is the greatest racecar of all time?…so we can cut the talk short. Without doubt, Dan Gurney’s Eagle-Weslake will always appear on enthusiasts’ lists of great racers. And the Eagle, with the Ferrari 156 Sharknose, the Alfa Romeo 158, the Auto Union, will always be described as “the most beautiful” or “the most striking” of all Grand Prix cars.

After meeting and talking with Dan Gurney a number of times, he got behind the idea that VR should do a test of one of his iconic F1 cars, and he put in a good word with people to assist, as there just aren’t many of these cars around…never were. In 2004, just before he went out to practice at the Monaco Historics, American Lou Sellyei agreed that it would be something we could do. A few minutes later, Lou was in the wall at Monaco, and a big repair job meant that the dream would be postponed. But when VR bumped into him at Phillip Island, Australia, in February 2006, the Eagle-Weslake was back in perfect shape. Lou jumped when he remembered what had happened the last time I talked to him, but agreed we could do the test. Bert Skidmore was entered to race it at Phillip Island but before we knew it, one of the all-time dream drives was going to take place.

All American and Anglo-American

The Dan Gurney story is far too complex, and far too fascinating to be able to record here, but in summary, Gurney launched All-American Racers in 1965 in order to participate in American USAC racing, particularly at the Indy 500. Retaining the British designer Len Terry also opened the door to fulfilling another Gurney ambition, that of running his own Grand Prix team. Dan had been in serious international racing since the late ’50s and had been a potent force in F1, though he never won nearly as many races as he should have. He had driven for Ferrari, Porsche, BRM and Brabham works teams. So shortly after the AAR factory opened in Santa Ana, California, a parallel operation was begun in Rye, Sussex, England, as a base for his Grand Prix team. The patriotic Gurney called the cars Eagles. The most memorable characteristic of these cars was that they did indeed look like eagles, with a dramatic beaked nose inspired by one of Len Terry’s designs.

Len Terry had first believed that Gurney was only going to build F1 cars, but Indy cars became the priority, and some historians will argue this is what prevented AAR from gaining success on the Grand Prix circuits. Of course, the counterargument is that the success of the American operation gave impetus to the F1 program. Gurney wanted to have a GP team ready for 1966 and, through his contacts with Aubrey Woods at BRM, he met Harry Weslake. Weslake had his base at Rye in Sussex so it was no coincidence that Anglo-American Racers set up their preparation shop next door. Gurney had been very impressed with some of the work that Weslake had been doing for BRM, especially with the 500-cc, twin-cylinder test unit he was developing that featured a four-valve head with narrow valve angles. It was this development that BRM put aside and opted for the H-16 engine instead for 1966, though they eventually had to give up and go back to the 12-cylinder. Gurney organized Weslake to build six engines for him. Gurney would turn out to be the only driver-turned-constructor who would not use a proprietary engine.

Photo: Casey Annis

When the new 3-liter formula started at the beginning of 1966, Jack Brabham and teammate Denny Hulme were ready for it, and the Eagles weren’t. When the Type F 101 showed up for the Belgian Grand Prix, however, it was striking both for its blue and white livery and its similarity to the Indy car. The team’s various factions had obviously been working closely together. Weslake had not managed to have an engine ready, so a 2.7 Climax—which was way past its sell-by date—did duty instead, mated to a Hewland HD5 gearbox. The Climax engine suffered from a severe vibration and this is alleged to have caused the great Gurney to stop for a “call of nature,” leaving the engine running with the wheels blocked as he did so! Spa that year was, of course, the famous scene of many cars crashing…and being filmed doing so…but Gurney wasn’t involved in this. He finished 7th but wasn’t classified.

Some refinements were made and the new car managed 5th at Reims for some championship points, though well behind the leaders. Dan then heaved the 2.7-engined Eagle onto the front row for the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch. Gurney held 1st, 2nd and then 3rd on the sweeping Kent circuit, but the engine broke a piston on lap nine and a fine show was over. At Zandvoort, Gurney was up in 6th when the head gasket, rear anti-roll bar and oil feed pipe all conspired to quit. It was even more heartbreaking at the Nürburgring when the Eagle, complete with underpowered engine, was holding its own in 4th place until the last lap. A bracket had broken which disconnected the alternator.

Chassis 1G 102

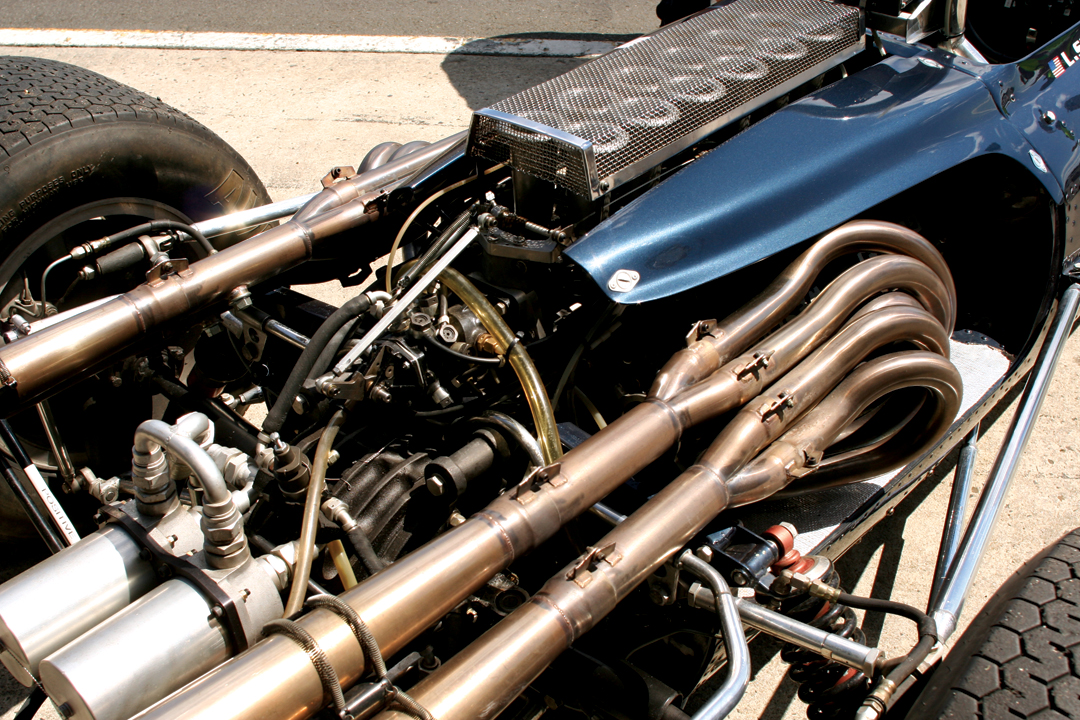

When our “test car” first appeared at the 1966 Italian Grand Prix at Monza, it was as impressive as its predecessor in appearance, and little had been done to change the full-length, riveted, aluminum monocoque chassis, with subframes for the front and rear suspension. The big…staggering…change was in the engine department where the Aubrey Woods–developed and Harry Weslake–built V-12 sat as the most compact V-12 anyone had ever seen. The engine was a 60-degree unit with twin overhead camshafts on each bank under a single cam cover. There was a single plug per cylinder arrangement, with the inlet valves in the Vee and the exhaust valves placed laterally. Chassis 102 came up against fuel feed problems in practice and these were alleviated but followed by very high oil temperatures, which caused Gurney to retire from the race. Phil Hill had been given 101 at Monza, but it wasn’t fast enough to qualify.

Bob Bondurant replaced Hill at Watkins Glen in 101, while Gurney showed the American crowd just what the Eagle was capable of. It was certainly one of the quickest cars in a straight line, with a terrific sound coming from the exhausts. But low oil pressure and a cracked fuel cell caused difficulties in practice. Gurney got to 8th in the race, but fuel was still a problem and oil leaked onto the clutch, which started to slip, leading to another retirement. Gurney put Bondurant into 102 in Mexico while he went for reliability in the older 101 and finished 5th. Bondurant retired after being disqualified at Watkins Glen, when he was unwillingly given a push start after being elbowed off the road at the start.

1967 and 102 Wins

Plans were being made back in California for the next stage of the design of the chassis where the aluminum skins would be replaced by magnesium and the steel parts by titanium on the new cars. In order to allow plenty of time for construction and testing, Gurney decided to take only the older 101 to South Africa in January, where he retired. Then 102 and 103 were sent to Brands Hatch for the Race of Champions, which would act as a test session, being not very far from AAR’s home at Rye. Chassis 103 was a new car but not built to the new specs at this stage, though it did have the latest version of the Weslake engine at around 400 bhp, while 102 had its older 360 bhp unit installed.

A great deal of work had been done over the winter on solving fuel and oil problems, and the obvious consequence of this was the thorough pounding Gurney handed out to the opposition. He had his new diminutive teammate Richie Ginther in 103, while he had 102 for himself. They annihilated the opposition in qualifying, with Gurney coming out a full second quicker than anyone else. Ginther did very well though this was not the all-new lightened car which had been developed, as that would appear a bit later.

Practice for the Race of Champions took place over two days. It was always an enjoyable and relaxed early season meeting, with some new cars about to appear, and with everyone in a relaxed mood. Gurney lowered the existing lap record by three seconds, with Ginther a second and a half behind. When Gurney won 100 bottles of champagne for fastest time on Friday, he pushed Harry Weslake forward to accept the prize. John Surtees was trying to disrupt the party with the first British showing for the new Honda V-12. Bandini’s 2-plug, 36-valve, V-12 Ferrari was putting out about the same power as the Weslake but was only 11th on the grid, while Amon withdrew after being hit by a “lady driver” on the way to the circuit and was injured.

McLaren (McLaren-BRM), Brabham (Brabham-Repco), and Rindt, Scarfiotti and Spence started behind the Eagle pair and Surtees for Heat 1, where it was freezing cold as 45,000 spectators watched Ginther get the jump at the beginning of the first 10-lap heat. Gurney got around him by the end of the lap, and he stayed there for all 10 laps. Ginther got taken by Surtees and that is how they finished. In Heat 2, Ginther again was in front, though Gurney passed him by at Druids Corner. The Eagle pair beat Surtees, Scarfiotti’s Ferrari and a charging Pedro Rodriguez in the Cooper-Maserati.

The final was over 40 laps, and only Denny Hulme and Guy Ligier were not able to race. Jo Siffert charged onto the back of Surtees as he chased the two Eagles, with Gurney in command. Rodriguez was also harrying Siffert, as McLaren’s engine failed on the first lap. Surtees was no longer a threat when he came in with a sticky throttle on lap 8 and eventually quit. Jack Brabham had forced his way through the field to latch onto Ginther, and got by on lap 10. As Brabham caught up to Gurney, Ginther fell back to a closing Siffert, who himself was fending off an improving Bandini. On the 17th tour, Brabham was looking to try and go around Gurney, but then disappeared, and came slowly into the pit lane with a misfire. At halfway, Bandini was now flying, getting past Siffert and closing on Ginther.

No one realized that Gurney was trying to survive low oil pressure, with smoke coming from one bank. The field closed up and Ginther dived into the pits on lap 36 with handling and other problems and was out of the running. Bandini closed on Gurney. The Ferrari had the pace but hadn’t been able to pass, but it was going quickly now. Gurney and 102 held off the Italian by under half a second. Siffert was 3rd ahead of Rodriguez. Dan Gurney had showed the world that the Eagle could fly.

The flight, at least for chassis 1G 102, was to be fairly short lived and undramatic. Gurney appeared at Monaco with 102 but swapped with Ginther. Gurney failed to finish at Monaco, and poor Ginther couldn’t get 102 qualified. He then failed to qualify at the Indy 500 and decided to call it a day. Chassis 102 then appeared only as a spare at the Dutch and French races, while Gurney tried the all-new 104. This car was radically different, and the mechanics were amazed at the quality of the titanium welding. It was, of course, lighter and Gurney was on the front row at Zandvoort. However, the fuel problems reasserted themselves and the new car was out after 9 laps. In Belgium, however, Gurney was again on the front row. Again, he had fuel-pressure problems and stopped, but this time he returned to the fray, flew the Eagle through the Ardennes, passed Jackie Stewart on lap 21, and won by a minute. It was spectacular, especially after Gurney’s win at Le Mans the previous week.

Bruce McLaren joined Gurney for three races as his own cars were being completed. He was given 102, which required an overnight engine change. He qualified well but the drive to the ignition sheared and it started to slip and begin to retard the ignition, causing retirement. Another engine change was necessary after practice at Silverstone for the British Grand Prix when a rod broke. This happened again in the race when McLaren was in 7th. Bruce’s final Eagle ride was no better at the Nürburgring where the heavy car bottomed and broke an oil-scavenge pipe. He pulled out to save the engine but wasn’t any happier that Dan had also retired in these last three races. McLaren was in 5th when he stopped at the German Grand Prix, but Gurney was on his way to another win when the drive-shaft universal joint broke with just over two laps to go.

There are some who say Scarfiotti drove 102 in its last Grand Prix at Monza and broke the scavenge pump but that is more likely to be 103. Chassis 102 seems to have been sold to Scuderia Filipinetti, but that team never raced it. It eventually found its way to America and, in recent years, to experienced racer and now historic driver Lou Sellyei, who brings it out on occasion.

Gurney had managed a good 3rd in Canada with 103 but retired in the last three races of the season in 104. Canadian Al Pease plugged on with old 101 attempting to run in the Canadian Grand Prix but not managing it. Gurney increasingly found that Weslake could not keep the engines competitive, and they were dogged with minor problems. As 1968 began, Gurney decided to split with Weslake and build the engines on his own. On a small budget, this was not practical. There were four retirements and one 9th-place for five races in 1968, and the increasing worry about the fire risk in magnesium parts helped to bring the end to hand. It was sad, as the car could be brilliant, and with a bit more luck would have seen some very impressive results. Indy cars, at the time, were “easy” and making money, so Gurney’s F1 construction came to an end.

Driving the Eagle-Weslake V-12

The VR crew…especially us “foreigners”…had found itself swept up on the south coast of Australia, well south of Melbourne, at Phillip Island. You can stand on the edge of the circuit and look out to sea and the next landfall is Tasmania or possibly Antarctica! It’s a long way away from what we are used to. What we were also not used to was the incredible Australian hospitality that greeted us. Now, I know we were among like-minded souls, but the Aussies were unendingly friendly and helpful.

When I go to certain circuits, I know—especially with a last-minute request to do something that will be a problem—I can predict the kind of look I am going to get. When we cautiously said to organizer Ian Tate that we would love to have a few minutes to do a photo shoot at the beginning or end of the day, he looked cautious, and said he would get back to us. Not only did he actually come back, but announced we would be the lunch-time entertainment! We had interrupted a serious and busy historic meeting and been allowed the circuit to photograph some interesting cars and do some driving. Why shouldn’t the spectators get a little more for their money? We were overwhelmed.

And so was I when I slid down inside Dan Gurney’s Race of Champions winner, some 39 years later. Gurney had said the car was very precise and I was going to find out firsthand.

There are several aspects of this car to get to grips with. The car itself is amazingly beautiful from the aggressive and shapely nose—the best nose of any Grand Prix car—to the solid sculpture of the exhaust system at the rear. The riveted precision is inherent in the design…it’s solid, dynamic…just stunning. Then you get in the car, and of course you can never do this on your own. This car always attracts people everywhere. The fact that you have entered something special is in the eyes of the beholders. I know why Lou Sellyei smiles, but I don’t know how Bert Skidmore keeps a straight face. The history is recounted to you in the expressions of all those around not lucky enough to be where you are. In all this it is hard to concentrate, but you are sitting on the plain but tidy alloy slab of the floor, with a back pad, but that is all.

There is reasonable room at the sides as the sun flashes off the perfect insides of the monocoque skin. It is hard to peer into the pedal area, and Bert reminds me that the brake pedal is raised…it’s higher than the rest. Only when he reads this will he realize that I wasn’t concentrating on that part of the lesson and would nearly bend the best beak in the business! For a car with so much charisma, the interior is simple and straightforward…the car is the charisma! The three-spoked wheel is thick and firm, making you feel like this is a machine to hang onto. There are only four simple gauges: a Smith’s rev counter reading to 12,000 rpm and three oil-and-water-pressure and temperature gauges. There is a minimum of switches, and the polished gearshift is poised below and to the right of the wheel. It’s all as if the car will do it with limited intervention from this intruder. Then there’s the starter button, which leads to the next level, the “symphony of 12” of Weslake’s cylinders. I can’t see the exhaust changing color as it warms up, but I know from the look on the faces that it is…fingers are pointing, the show is getting ready to roll. With almost a disappointingly easy snick of the lever connected to the Hewland DG300 gearbox, Eagle-Weslake 1G 102 points its sexy beak out into the road and prowls down the pit-lane. I am only vaguely mindful of heads snapping as this unscheduled bird goes out on the lunch hour. I have to fight, this time, to keep my mind on the job because rarely have I been so aware of the iconic nature of what I am sitting in. I hope the bird of prey doesn’t find that kangaroo we saw earlier running across the circuit and under the fence!

Phillip Island is longish and undulating, with a flat blind brow at the end of the pit straight and wide sweeps that angle left and take you in the direction of a fabulous sea view. After an hour, a few days earlier, rushing around the madness of the rising and falling Bathurst circuit, this is a day at the beach, though a tricky beach to be sure. There are banks and trees and up and down sweeps, which tighten at a glance, off-camber slopes where every bit of power is needed for a good time. This is Eagle country.

Chassis 102 warms to the task and emits a steady and growing burble, then a rush and then a whine. The gearbox clicks precisely, as Dan said, up and down. At slow speeds, there was no need for the brakes and, with no pressure, I warmed them up. Then as I came up on the camera car, it changed line in a tight, descending right with sand and gravel on the left, and I was coming up too fast, and snatched for the brake. It wasn’t there, and I panicked until I remembered that it was a high pedal and just got my toe on it as I headed onto the edge of the gravel in avoidance and shot past the camera car. Don’t get carried away during briefing time! I pushed the thoughts of how I would have explained bending the world’s most lovely proboscis away, and got back to driving.

The car is again, as Dan said, very precise. It moves with the slightest touch of the wheel, surprisingly sensitive to me, and it takes some getting used to. But everything else is precise as well: the throttle is responsive and feeds the power in without effort, and there is no struggle from that revered engine at the back. The struggles were sorted way back when. On this less-than-easy circuit, the Eagle turns in beautifully…you can pause your mind on the downhill turning-in points and just capture that gorgeous front end spearing into a corner. Chassis 102 eventually had some of the lightweight suspension put on it, and it seems to be working, creating a feel of perfect balance on entry and exit from the corners, with a hint of dive to tell you what is happening, but no undue activity at the rear. Having raced on the Brands Hatch Grand Prix circuit, I can see where this car would be at its best, ripping out of medium and fast corners, storming through Hawthorns at the back of the circuit. At Spa, however, this must have been an almost unreal experience. We’ll have to get Dan to tell it. In the meantime, I’m still grinning.

Specifications

Type: Eagle 1G

Constructed: 1966–67

Number made: 4 including one Type F

Chassis: Full-length riveted aluminum mono-coque chassis with subframe for front and rear suspension.

Front suspension: Lower wishbone, upper rocker arm oper-ating inboard coil spring/damper units.

Rear suspension: Double struts, two forward running radius arms, outboard coil spring/damper units.

Engine: Aubrey Woods and Harry Weslake designed V-12

Capacity: 2997 cc

Cylinders: 12 in 60-degree Vee formation

Bore and stroke: 72.8 mm x 60.3 mm

Valves: 2 inlet per cylinder in Vee, 2 exhaust per cylinder laterally

Carburetion: Lucas port fuel injection

Ignition: Lucas OPUS

Camshafts: 2 overhead per bank

Gearbox: Hewland DG300 5-speed

Brakes: Outboard discs

Resources

Thanks to Lou Sellyei for the experience, to Bert Skidmore for the help, and to Ian Tate and Phillip Island for being great.

Ellard, C. The Forgotten Races. W3 Publications. Surrey, England, 2004.

Sheldon, P. Milestones Behind the Marques. D. Charles Publisher. Canada, 1976.