Photo: Jeff Bloxham

The British motor industry has had a rather checkered history since it began in the late 19th century. At its zenith there were between 150 and 200 motor companies, as early as the first part of the 1920s. During the Great Depression, in the latter years of that decade, between two-thirds and three-quarters of those companies disappeared, either through bankruptcy or amalgamation. Obviously, the war years produced a national effort directed toward saving a nation, and car production literally took a back seat to military defense. Post-war, as the country and the car industry returned to a somewhat normal service, the British motor industry once again became lively and prosperous. As the early 1950s dawned, the UK was the second biggest manufacturer of automobiles in the world—only the U.S. produced more—and the biggest exporter of cars in the world. Enjoying this latest boom, on reflection, it was rather naive to think the industry would continue to flourish, or even sustain the then current trend.

By the late 1960s, national and world events had brought a severe decline in the industry to the point where amalgamation and government nationalization were thrown at it as life buoys. Despite this, however, the erosion continued with emerging markets from Europe and far eastern countries such as Japan taking trade away from the UK. The 1970s found British Leyland bankrupt and needing government funding to survive. Poor management decisions, quality control issues and mediocre models, together with the oil crisis and a certain trade unionist (Derek Robinson, colloquially known as “Red Robbo” and described by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher as a “notorious agitator”), collectively took the industry to a nadir from which it has never really recovered. However, against this background, cars were still being produced to try and inject new life into an ailing patient. This included the road model of our profile car the Rover SD1—something of a major step forward in terms of styling for an executive car.

The Rover marque

The Rover marque began life in the Midlands of England in the 1870s, known as the Starley & Sutton Company of Coventry, they built bicycles and motorcycles before turning to automobiles as the UK became gripped by this new mode of now affordable transport. Thought to be a lucrative move, it turned out to be anything but. Despite much world publicity in the early 1930s for the “Blue Train” race where the Rover Light Six beat the Calais to Cannes Mediterranean Express train, the Rover Car Company’s history was on a continual “knife edge” financially speaking, but enjoyed those halcyon years of the 1950s to early 1960s. Rover also dabbled in new technology producing several gas turbine models, most notably the Rover-BRM that raced at Le Mans in the hands of Graham Hill and Richie Ginther. Diesel engine cars were added to the mix, as well as other experimental designs, as the company fought to be at the cutting edge of the market.

Photo: Kary Jiggle

As a manufacturer, the Rover marque specialized in executive models such as the Rover 80, or P4, and the P5 and P6 models. Ironically, it was the utilitarian Land Rover that made the lion’s share of the money for the company. Moving forward to the mid-1970s, by then under the umbrella of British Leyland, the SD1—simply called as it was the first of the Specialist Division projects to replace the now outdated Rover P6 and the Triumph 2000 models made its debut. Understanding the background, thoughts and interests of the designer of a particular car gives us some clue as to how and why that car ended up the shape it did in that point of motoring history. From a road car point of view, the car was once again for the executive market and aimed to give various degrees of luxury from the cheaper basic two-liter model to a more expensive and exclusive three-liter V8 automatic. The road cars were first produced in 1976 and continued production with various upgrades and redesigns for the next decade. Stalwart Rover employee and architect David Bache headed the design team responsible for the car. Bache, born in Germany, was the son of famous Aston Villa and England professional footballer, Joe Bache. Not wishing to take up a career in sport, he served his apprenticeship with the Austin Motor Company under the guidance of Argentinian Dick Burzi—a former automotive designer with Lancia and recruited by Herbert Austin, following Burzi’s political outburst and disparaging cartoons of Benito Mussolini, Italy’s fascist leader. In the early 1950s, Bache moved to Rover, becoming the company’s first ever “stylist,” and worked on the Rover 60, 75 and 90 models. He was greatly influenced by French and Italian styling, particularly Flaminio Bertoni’s ground- breaking Citroen DS and the Facel Vega of Jean Daninos and, of course, the work of renowned coachbuilders such as Ghia and Pininfarina.

Rover SD1 road car

After a number of years on the drawing board and in the design studios perfecting the ultimate design, the first Rover SD1 was unveiled to the press and public midway through 1976. It was immediately bestowed with the prestigious “European Car of the Year” award for 1977—to date, the very last time a British car was honored by such an accolade. Styling-wise this was brave new thinking, the heavy box-type designs formerly synonymous with executive models had now been replaced with a much lower, sleeker and sportier looking lines—sans the usual distinctive front chrome radiator, which was replaced by an air scoop, or intake below the front bumper. The frontal design, with enveloping front light cluster (necessarily redesigned for the U.S. market), bore much resemblance to the Leonardo Fioravanti-penned, Pininfarina-styled, Ferrari 375 GTB/4 Daytona. The equally sleek rear shape of the car was audaciously finished with a “fifth” door, or hatchback. A new Rover V8 power unit powered this initial model (a number of engines were used, dependent upon final finish—this was a car that could be ultimately built as a relatively cheap economical four-cylinder engine, 5-speed manual gearbox model through to a significantly more opulent top of the range Vitesse) and drive was through a three-speed Borg-Warner automatic gearbox. Outdated rear drum brakes and the use of a live axle were anomalous to this otherwise advanced new vehicle. The ugly specter of poor production and the constant staccato of interruption by various industrial actions, resulting in many total walkout strikes instigated by Red Robbo, ensured the British government-owned company wouldn’t make any beneficial monetary remuneration from this innovative automobile.

Motorsport

Since the mid-1950s, like many worldwide marques and manufacturers, the British Motor Company (BMC) and the evolutionary titles including British Leyland (BL) and Austin Rover have gained much good publicity to aid national and international car sales. Luminaries of British motorsport including Marcus Chambers, Stuart Turner and Peter Browning have all headed this department. Despite being ideally suited aerodynamically, the Rover SD1 was not initially looked upon as something to be used in competition. In fact, up until the 1980 season, the regulations for the British Saloon Car Championship (BSCC) precluded cars with engines exceeding three liters. These rules were relaxed in 1980, however, to allow the use of 3.5-liter engines, so the door to competition was opened for the SD1. Despite this, the incumbent BL Competitions Department team manager, John Davenport, had to work hard and get significant support before he could convince the hierarchy of the BL Board that competition was right for the SD1. Davenport had spent most of his racing career as a professional rally co-driver to many of the top names of the sport, including Ove Andersson, Timo Makinen, Hanu Mikkola and Vic Elford, and appreciated the benefits a successful racing campaign for the car could produce.

By 1979, much testing and development of the SD1 chassis was done by BL Motorsport in collaboration with Dave Price Motorsport. Price had been racing for a few years in F3, running drivers like Nigel Mansell and Martin Brundle in their formative years. History shows his many successes over subsequent years including a Le Mans victory in 1989 with Sauber-Mercedes, the winning of both driver and constructor championships with the McLaren F1 GTR and the initial running of Team USA in the now defunct A1 Grand Prix World Series. While the Rover with its very low and smooth lines, wide track, suspension system and well-balanced characteristics was ideal for racing, upgrades were very necessary for the arena of competition. Two cars were produced to enter the 1980 season of the BSCC. Rivalry would come from a number of sources, including Gordon Spice in the Ford Capri, but most significant was from Tom Walkinshaw in his very successful TWR-prepared Mazda RX-7.

Photo: BRDC Archive

With title sponsorship from Triplex and Esso, the 250-hp Rover 3500 S drivers were named as Jeff Allam, in his third season of BSCC racing, and Rex Greenslade. Racing in Class D, they produced a reasonable year with the car showing much promise, including a well-deserved Allam victory in the Empire Trophy race at Brands Hatch, but it was plagued by unreliability—mainly in the engine department. It was during this initial racing season that Tom Walkinshaw was asked to get involved with the project, as he told me when I interviewed him a few months prior to his passing. “The SD1 Rovers were in the same championship as the Mazda, they were run out of the factory in Abingdon. The cars kept blowing up and weren’t very quick—just embarrassing, it was a complete disaster area. I think it was at Thruxton when someone from the Rover team came and asked if I could take a look at their car to see where things were going wrong. I ended up lying underneath their car in the paddock, evaluating their problems. I looked carefully at what they’d got and the way they had put things together. I was asked for my thoughts. I told them there were a number of issues and problems where the car could be made more competitive. I was asked if I, or rather TWR, could do anything for them. I said we could help, but it would have to be for a price. They asked for a number, which I duly gave—naturally it caused them to faint! We ended up doing a deal; it was for £1,000 for every tenth of a second we could better their lap times—to a maximum of £20,000. It was two weeks before the next race at Silverstone. In the meantime, we prepared the car by making improvements to the inlet manifolds, the suspension, and other things. To cut a long story short, at Silverstone the car was on pole! So, from an ‘also ran’ we had made a car 2.8 seconds faster than it had previously been. It pleased Rover, but made life a little more difficult for us and our Mazda. Rover duly paid out our £20,000 and asked us to talk to them at the end of the season, which we did, and that led to us having a contract to prepare the cars for Rover.”

In 1981, TWR took a more hands-on role with the Rover, entering Jeff Allam, now recruited by TWR to race the car under Walkinshaw’s banner, and Pete Lovett as a sometime teammate. TWR also ran a brace of Mazda RX-7s and indeed Martin Brundle and Stirling Moss aboard a pair of Audi 80 GLE cars—Moss’ first “official” regular racing comeback since his 1962 Goodwood accident. Patrick Motorsport, with major sponsorship from ICI and Duckhams Oil, also ran two Rover 3500 S cars for Rex Greenslade and veteran Aussie driver Brian Muir. South African Rad Dougall contested Round 11 in a third entry. It was Lovett in the Daily Express TWR-prepared car that took the first victory of all the Rovers during the 1981 season, at the Marlboro F3 racing weekend. He won again a few weeks later at the same circuit in the British GP support race, this time with Allam completing a famous 1-2 finish. Allam took the final wins of the 1981 season at Thruxton and Silverstone respectively. The 1982 season built on the success of the previous seasons with the SD1 taking further victories and an overall class win. While preparing racing cars, TWR also prepared a number of long-distance rally cars. These were not as successful as the road racing cars, but went a long way to building the competitive reputation of the car.

Birth of the racing Group A Rover SD1 Vitesse

In 1982, the launch of the road version of the Rover SD1 Vitesse with now stiffer suspension, fuel injection and various styling appendages including a zero-effect, but very sporty, rear spoiler was directly due to recent motor racing success and the public’s thirst for a more powerful car and the need to homologate a more powerful racecar—a minimum of 5,000 vehicles were necessitated for this purpose, which sales-wise “flew off the shelf.” The BSCC evolved their racing regulations and for 1983 it was decided to run to the new FIA Group A regulations. TWR worked tirelessly to produce new cars complying with the new regulations enabling the team to compete along a broader band of competition, which would include Blue Ribbon ETCC races, such as the Spa 24 Hours, and other domestic production series in both France and Belgium. Of course, in 1983 Walkinshaw and his TWR race preparation company began to work with the Jaguar XJS, but that’s another story. Group A regulations required much redesign not only to the Rover engine, but the chassis too. A new active rear wing—as opposed to the decorative road car spoiler—ably assisted by the sloping tailgate rear bodywork, increased backend downforce of the new racing version and combatted the lifting seen in previous cars. New 15-inch alloy wheels were fitted and, of course, the new fuel-injected engines were also added. The total weight was increased by 50 kilograms above the previous BSCC rule to 1185 kilograms. The external coachwork was required to mirror that of the road car exactly. While there were restrictions, significant freedoms were allowed in other departments like gearbox, rear axle, suspension and brakes.

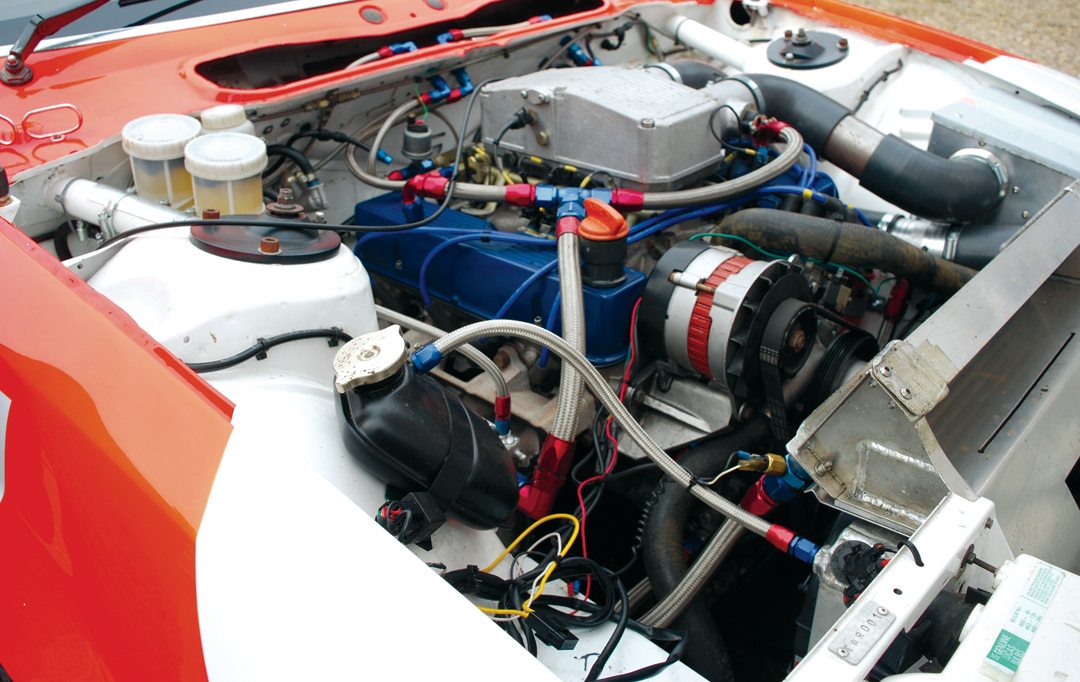

TWR worked in tandem with the new Austin Rover Group Motorsport (ARG) to assist with the heavy workload and production process to get the cars on track for the coming season. There were many headaches and dilemmas associated with understanding and applying the new engine rules. The new car with fuel injection was supposed to increase power from the 250-hp of the previous season, but with restrictions on engine tuning, exhaust manifold design and air intake the previous 250-hp wasn’t a target they could achieve, let alone exceed. The Lucas units were replaced at a cost of £400 per car with the more reliable Zytek-designed models—this gave the cars an initial edge at the beginning of the season.

TWR ran three Rover SD1 Vitesse cars in the BSCC, driven by Jeff Allam, and Peter Lovett in blue Sanyo-liveried cars and Steve Soper in a privately funded gold-colored Hepolite Glacier Racing-sponsored car. At the first meeting of the new season, the Silverstone International Trophy, in very damp and soggy conditions, the three cars simply blew away all opposition finishing 1-2-3 (Soper, Allam, Lovett). Much to the chagrin of other competitors, particularly BMW, the SD1 cars completely dominated the 11-race series, but to no avail. BMW challenged the design of the Rover, with particular reference to the wheel arches that didn’t exactly mirror those of the road cars. The authorities upheld the challenge and the TWR team was excluded from all the 1983 BSCC results. Steve Soper should have been champion driver, but was replaced by Andy Rouse driving an Alfa GTV6.

Our profile car, chassis 001, is the initial test and development TWR Group A car that logged many miles of development driving prior to competing in the 1983 French Production Car Championship (officially titled Championnat de France de Voitures Production). Andy Harrison managed the TWR/ARG team entry, and René Metge would compete in all 14 rounds of the championship. Metge was a 41-year-old racer who had his own British Leyland dealership on the outskirts of Paris. He was the current champion, winning in a Rover 3500S. He was a maverick racer and took on many a challenge, from Le Mans to the Paris-Dakar—indeed he won the latter event in 1981 in a Range Rover.

The French National Production Series, in 1983, were running to ETCC Group A rules, as has already been mentioned, but the French being the French, had certain exceptions to those rules and allowed certain relaxations in engine setup and aero packages—this suited both TWR and ARG Motorsport as many parts used in the 1982 BSCC series could now cross over to the 1983 French series rather than being obsolete. Racing regulations in the French Championship included success ballast, this was supposed to even the playing field in a series that included lighter-weighted Alfa GTV6s and Peugeots against the heavier BMWs and, of course, the Rover SD1. Like many rules there were ways that the teams could strategize by finishing lower in one race to gain an advantage at the following meeting—all very unpredictable.

Metge qualified the Rover in a mediocre 10th place for the first round of the championship at Montlhéry, but was disqualified from the results after being push-started during the race. The next round at Nogaro produced an improvement in grid position, but an accident left the team without points as it headed to Paul Ricard. Following revision to the fuel injection trumpets, Metge managed to finish 5th, albeit 15 seconds behind the victorious Chevrolet Camaro. Another 5th at Magny-Cours, Round 4 of the series, showed signs of progress; this was underlined at the following meeting at Dijon where Metge finished on the podium in 3rd place in the first heat of a doubleheader meeting, although he didn’t start the second heat. Minor placing on the street circuit at Pau in another two-heat meeting was the prelude to bigger and better results at La Chatre, 2nd, and victory at last at Rouen. Metge visited the top step of the podium once more during the season, at Croix en Ternois, winning Heat Two and taking overall victory on aggregate at the doubleheader event. Although there were no further victories, Metge had done enough to amass 209 points by season end at Montlhéry and finish a very respectable 4th in TWR’s first year of competition in the French series.

Building on this success, TWR upped the game and entered a brace of SD1s for the 1984 edition of the French series, with a more comprehensive support package for the team—although Tom Walkinshaw himself didn’t appear at any of the rounds. The cars, once again ran to the relaxed Group A regulations, as in 1983. TWR saw the French series as an ideal testing ground for experimental aerodynamic and engine modifications, some of which could be translated to other racing series. Despite his solid racing year, Rene Metge was dropped as a driver for this second year and replaced by Jean-Louis Schlesser and Marc Duez. Schlesser had shared the 1978 Formula Three championship with Alain Prost and had finished 2nd on his debut at Le Mans. With previous experience in the French series, he was looked upon as being a stronger competitor than his French counterpart. The young Belgian, Marc Duez, was seen as an ideal teammate to keep Schlesser on his toes.

The French Peugeot team were the guys to beat in 1984, fielding three 505s for their very experienced drivers—J-P Beltoise, J-P Jabouille and J-P Malcher. While Beltoise and the Peugeot team took the spoils in the opening rounds of the new season at Montlhéry, Schlesser was king at Nogaro with pole position and overall victory in the race. This success was short lived as the Peugeots heaped more pressure and took a grip of the series for the next three rounds. The double-header at Rouen found Schlesser taking overall victory again with a very close 2nd place in Heat One and victory in Heat Two. Engine problems dampened spirits and curtailed form at the next round at Clermont-Ferrand.

Although winning ways were resumed at Nogaro—a six-second gap back to Beltoise—it would be the last time the SD1 would seriously challenge for the title. It was a 5th-place finish in the championship behind the winning Alfa Romeo of Dany Snobeck and the mighty Peugeot team. While Schlesser would go on to take the 1985 French championship, chassis 001—trail blazer of the TWR Group A touring car program—was retired and used as a show car by ARG Motorsport, repainted in BASTOS livery synonymous with the marque’s successes in the ETCC with Jeff Allam, Win Percy and Tom Walkinshaw himself. The Marlboro colors, while relevant to the French motor racing community, meant little or nothing to the UK. Over the years, the car eventually found a home at the former Gaydon Heritage Center—now the British Motor Museum. In later years, the car was sold to a rally driver in Weston-Super-Mare, England, who campaigned Rover SD1 cars at various events. The car, however, didn’t see any active duty since it was purchased purely as a complete spare car—or rather bodyshell should it be required.

In 2012, by quirk of fate, the car completed a full circle when it was purchased by the current owner, Richard Postins, and restored by former TWR employee Ken Clarke, who worked on the Rover SD1 project in period. Clarke had also prepared cars for Postins’ father, prior to joining TWR and, over the years, had become a family friend. Richard Postins, already an accomplished driver and champion in the Masters Series with a blisteringly quick Austin A40, as well as an overall podium and class winner in the ultra competitive U2TC European series with Laranca BMW as teammate to Richard Shaw and Jackie Oliver, was considering a new challenge and looked at a new series, the Heritage Touring Cup run by Peter Auto, for 2014. With all of 2013 spent restoring the car to its 1984 specification, it was then successfully campaigned in the new series, which Richard won.

Driving the TWR Rover SD1

We are at Donington Park on a sunny, dry, crisp winter’s morning. As I gaze toward our Marlboro-decaled steed for the morning, a livery more associated with the successful McLaren F1 cars and Penske Indycars of the last century, I’m transported back in time for a brief moment as I owned a Rover SD1 roadcar in the early 1980s. My car was finished in arctic white paint that bears some resemblance both to today’s ambient temperature and the base color of chassis 001. However, the similarity stops as soon as the driver’s door is opened, instead of entering a vehicle of opulent luxury this is the “office” of a serious racing car.

The real jolt back to reality is completed as a stark basic interior is revealed, gone is the sumptuous leather seating, door panels, roof lining and other accoutrements associated with lavish interiors, these have been completely stripped out to reveal a basic bare metal internal finish. The only extravagance afforded to this toned competitor is a hefty roll cage to aid driver safety should disaster strike. Sitting in the minimalist, but workmanlike, “office chair” from the outlook through the screen the driver position has changed markedly from the road car, driver comfort and visibility is replaced by the need to find the optimum center of gravity—the seat therefore is much lower.

Having initially got the car to temperature and completed a couple of installation laps we’re now ready for a proper run. In these initial circuits, we’ve had to get used to driving a relatively heavy car without the comfort of power steering. Of course, power steering wasn’t used in period and certainly Tom Walkinshaw would have given that certain stern grimace of disapproval had any driver questioned the steering. The other thing quite noticeable is the braking distance needs to be a few yards earlier than you would particularly expect, but all told the car seems nimble, well-balanced and quite direct given its size. So, we’re now approaching the start-finish line and heading toward the right turn at Redgate, in fourth. Just after the pit lane exit there is a white inverted “V” shape painted on the road surface and we head left and toward the point of the V to get the optimum entry for the right-hander, changing down to third and turning quite early we’re able to wash through Redgate easily, using quite a bit of apex on the inside. Smoothly increasing power as we exit Redgate, changing up and trying not to use the curb, we prepare for the shallow right at Hollywood and then the Craner Curves. At this point, we’re driving downhill and easily picking up speed. There are those drivers who would simply take this flat, but this is not the way in the Rover—especially in cold ambient conditions and the obvious lack of road surface and tire temperature. On a hot, sunny summer’s day with sticky tires our driving style would be totally different—today, we’re driving within our limits. Exiting Hollywood we prepare for the more abrupt but smooth left, good speed, but not flat, or we could find ourselves in the “kitty litter” at the Old Hairpin. Through the right at the Old Hairpin, in third, we use a great deal of curb, the idea is to keep the momentum of the car alive as we start to climb under the bridge through Starkeys, flat through the shallow left at Schwantz Curve and up to the sharp right at McLeans. McLeans is a blind right-hander taken in third gear, with more room on exit than you believe you have. Exiting McLeans is assisted by a slight downhill gradient until it’s back uphill toward the double-apex Coppice. There’s a slight floaty feeling just prior to Coppice due to being directly on the flight path for East Midlands Airport, this is also felt at Redgate too, but to a lesser extent. All vision of the track is lost for a brief moment due to the low seating position and the circuit geography…so good memory is required.

Thankfully, due to recent improvements to the circuit, under the guidance of Circuit Director Christopher Tate, the hole that once caught many people out when taking too much curb has now been filled in, so it’s entirely possible to hug the apex as much as possible without the fear of any reprisal. There is a brief red mist moment that could induce a driver to floor the right pedal here, but caution is required on exiting the first part of Coppice onto the second apex of the corner to get the ideal entry to the fastest part of the long straight—where the old Dunlop bridge used to stand—we’re now pulling maximum revs, around 7,200, for the lap and approaching the last corners as we’re on the short circuit. The braking here is marked by being in line with the last fire exit door of the Exhibition Centre (on the left side) this gives the ideal entry to the Roberts Chicane. There’s no way we can take any curb here as they are far too high, so hard braking down to second gear as we turn right—momentum is the watch word again—as we turn hard left and progress up to fourth and maximum speed across the start-finish line to complete the lap. Of course, our lap has been a traffic-free tour without any obstruction. In race conditions, there have been issues with tramping—so late braking is a very careful maneuver precisely done to achieve ultimate advantage.

Epilogue

In the current historic series in which the Rover competes it is interesting to understand that the SD1 is probably the least powerful of all the entrants, which include such cars as the BMWs and Cologne Capris. Of course, in period, the SD1 had the measure of many of its rivals and produced great results—even though some were expunged by regulation infringements. The Rover SD1 was a very capable racer, it should have been the holy grail of the British motor industry, but political and industrial working issues significantly reduced the impact the car had on the UK market. Sales figures of the previous Triumph 2000 and Rover P6 models amassed some 650,000, the replacement Rover SD1 was at least supposed to emulate those numbers, but barely managed half that amount.

Competitively speaking, despite the politicking and controversies, the Rover SD1 stood up to most challenges in many forms of the sport, both on and off track. However, in motor racing you’re only as good as your last race, and time and a tide of other marques soon overshadowed the performance of the Rover SD1. Today, many enthusiasts remember the competition cars with much affection and deep sentiment—although many road car users still bitterly complain about the poor finish and build quality. For Tom Walkinshaw, the SD1 race program had shown his TWR team had the ability, experience and logistical knowledge to take on the world.

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine: 3500-cc

Max rpm: 7300 rpm

Gearbox: Getrag

Brakes: AP Lockheed / All bespoke brake components are made by KCM.

Rear axle: Bespoke to Group A cars utilizing CV joints within the rear axle to obtain negative camber on the rear.

Suspension: McPherson Strut front and coilover rear using Bilstein dampers. Front uprights are bespoke cast aluminum centerlock hubs all round

Wheelbase: 2815 millimeters

Track: Track must fit within the homologated bodywork.

Tyres: Yokohama 260/640 x 17 all round.

Weight: 1197 kilograms / 2633 pounds

Resources / Acknowledgements

British Leyland Motor Corporation 1968-2005: The Story from the Inside by Mike Carver, Anne Youngson and Nick Seale

Wheels of Misfortune—The Rise and Fall of the British Motor Industry by Jonathan Wood

TWR and Rover’s SD1 by Allan Scott

Rover SD1: The Complete Story by Karen Pender

Periodicals: Motor Sport / Autosport

Special thanks to:

Richard Postins for allowing us time with his car Ken Clarke of Ken Clarke Motorsport for his kind assistance