Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the McLaren F1

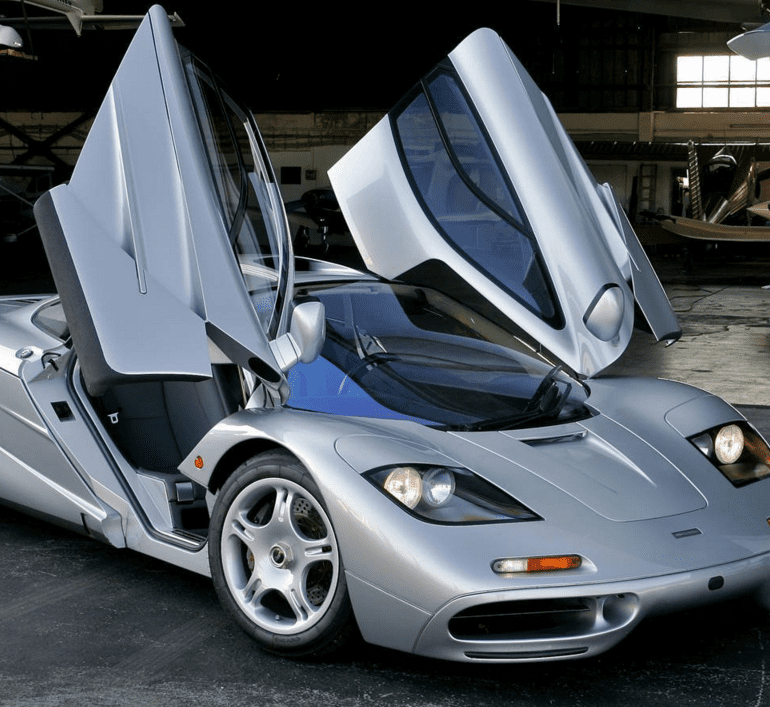

In 1992, McLaren took the supercar market by storm with the astonishing McLaren F1. It was a supercar like nothing before it. It was light, fast, agile and it absolutely obliterated just about every record in the books.

Amongst the firsts, the McLaren F1 was the first production car to feature a carbon-fiber monocoque and a center-mounted driver’s seat, among many other unique features and innovations. It became the world’s fastest production car at 240.1 mph.

We’ve written about the McLaren F1 in detail so we won’t do that again. Instead we wanted to use this post to tell you about some of the things that you may not know and to summarize all the facts and stats about this legend. Enjoy.

McLaren F1 Engine & Performance

McLaren F1 Engine

| engine | BMW S70/2 60 Degree V12 |

| position | Mid Longituinal |

| aspiration | Natural |

| valvetrain | DOHC w/4 Valves per Cyl |

| displacement | 6064 cc / 370.0 in³ |

| bore | 86.0 mm / 3.39 in |

| stroke | 87.0 mm / 3.43 in |

| compression | 10.5:1 |

| power | 467.6 kw / 627.1 bhp @ 7400 rpm |

| specific output | 103.41 bhp per litre |

| bhp/weight | 550.09 bhp per tonne |

| torque | 649.4 nm/479.0 ft lbs @ 5600 rpm |

| redline | 7500 |

McLaren F1 Performance

| Top speed | ~386.4 kph / 240.1 mph |

| 0 – 60 mph | ~3.2 seconds |

| 0 – 100 mph | ~6.7 seconds |

| 0 – 1/4 mile | ~11.6 seconds |

McLaren F1 Specifications

The Basics

| type | Series Production Car |

| production years | 1992 – 1998 |

| released at | 1992 Monaco F1 |

| built at | Woking, England |

| body stylist | Peter Stevens |

| coachbuilder | McLaren |

| engineers | Gordon Murray |

| production | 65 |

| price $ | $ 970,000 |

McLaren F1 Size

| curb weight | 1140 kg / 2513 lbs |

| wheelbase | 2718 mm / 107.0 in |

| front track | 1568 mm / 61.7 in |

| rear track | 1472 mm / 58.0 in |

| length | 4288 mm / 168.8 in |

| width | 1820 mm / 71.7 in |

| height | 1140 mm / 44.9 in |

McLaren F1 Body

| body / frame | Carbon Fibre Monocoque w/Front Upper Sub Frame, Active Aerodynamics |

| driven wheels | RWD w/Torsen Differential |

| front tires | Goodyear F1 P235/45ZR-17 |

| rear tires | Goodyear F1 P315/45ZR-17 |

| front brakes | Unassisted Vented & Crossdrilled Discs |

| rear brakes | Unassisted Vented & Crossdrilled Discs |

| front wheels | F 43.2 x 22.9 cm / 17.0 x 9.0 in |

| rear wheels | R 43.2 x 29.2 cm / 17.0 x 11.5 in |

| steering | Unassisted Rack & Pinion |

| f suspension | Ground-Plane Shear Centre Double Wishbones |

| r suspension | Double Wishbones w/Light Alloy Dampers |

| curb weight | 1140 kg / 2513 lbs |

McLaren F1 Questions & Answers

How much horsepower does a McLaren F1 have?

The McLaren F1 has a top speed of 240 mph (386 km/h), restricted by the rev limiter at 7500 rpm. The true top speed of the McLaren F1 was reached in April 1998 by the five-year-old XP5 prototype.

When did the McLaren F1 come out?

Production of the original F1 began in 1992. The LM model was then introduced in 1995, followed by the GT model in 1997. The GTR was built from 1995 through 1997. Production of the McLaren F1 drew to a close in May 1998, with a total production of 100 cars.

The F1’s engine bay was lined in gold.

Gold’s the best reflector of heat, and the F1’s engine ran very hot. Gold foil was installed to protect the car’s carbon fiber.

How much is a McLaren F1?

If you’re wondering how much a McLaren F1 would sell for in today’s market, a price of around 3.5 million pounds (approximately $5.58 million) is a good starting point. That’s the price that famous British supercar dealer Tom Hartley recently sold one at.

Who makes the McLaren car?

In 1999, McLaren agreed to design and manufacture the SLR in conjunction with Mercedes-Benz. DaimlerChrysler was the majority shareholder of the McLaren Group as well as engine supplier to the Team McLaren racing team through its Mercedes-Benz division.

What was the McLaren’s acceleration and top speed like?

The McLaren F1 is capable of 0 to 60 mph in 3.2 seconds and a top speed in excess of 240 mph. This made it the fastest production car in the world at the time. A fun fact was that the McLaren F1 was actually faster than contemporary F1 cars of the time above 130mph.

During development work, McLaren driver Jonathan Palmer drove F1 prototype XP3 around Italy’s 7.5 mile Nardo test track at 231 mph. But for the tight nature of the track, the car could have gone even faster. Early in 1998 this record was broken at Volkswagon’s test track with a recorded speed of 241 mph.

Tell us more about that engine.

Powering the McLaren is a quad cam, 48-valve, 6.1-litre BMW V12 engine with variable valve timing. It produces a staggering 627 bhp. The F1’s engine uses competition inspired dry sump lubrication. More complex than a conventional wet sump, it shaved vital inches from the oil pan, allowing the engine to be mounted lower.

Everywhere you look on the McLaren, attempts have been made to reduce weight. Like the front and rear wishbones which are machined from solid aluminium alloy; or the wheels, constructed out of magnesium alloy.

What about the seating position?

One key design feature of the McLaren F1 is the positioning of the driver – in the middle, with two passenger seats aft of either side. That makes everything equi-distant from the wheel.

It looks small.

It is, especially compared to today’s massive supercars. In fact it is smaller than a Porsche Boxster.

Your F1 at home is more powerful than the race version.

That’s right folks. The F1 that won Le Mans was less powerful than the road car due to rules on air restrictors.

Ron Dennis left the team alone.

Ron Dennis never saw the F1’s design until it was finished. That’s amazing given how much control he likes to have. Wow. 2) Two thicknesses of washer was available to the design office – a designer had to justify using a thick one.

Weight saving was an OBSESSION.

Here are some of the things the team did to save weight.

- 1.2mm. That was the thickness of the carbonfiber body.

- The toolkit was also custom engineered to save weight (tools were titanium)

- Same for the Kenwood stereo. In fact, several potential partners were selected. Five walked out when McLaren gave them a 50% weight-saving target. But Kenwood stayed on board and made its stereo half the weight.

- They even saved 5kg by shaving leather to half usual thickness

It almost had a different engine.

A Honda V10 or V12 approximately 4.5 litres in displacement was originally on the short list. That was mooted before the 6.0L BMW V12 was chosen.

Even the air conditioner was complicated.

The F1’s central air intake caused a few engineering headaches. ‘We had to design a water separator, trap and drain to avoid filling the engine with water when following a truck in the rain!’ recalls Murray.

Nice touch.

Tag Heuer launched an owner’s watch with each F1’s chassis number engraved on it – as did a matching luggage set. McLaren customers could even buy a custom made golf bag designed to be strapped into the passenger seats.

No remote start on the F1.

Starting a McLaren F1 is quite a ceremony. The inspiration for the lift-up flap over the starter button came from a WWII fighter firing button. ‘I really wanted the start to be an event,’ says Murray. ‘We cancelled the electronic signal to the starter for two full rpm so that the driver could hear that starter engage.

Three seats? Central driving position.

The McLaren F1’s unusual three-seat layout was designed to fix two of the worst supercar problems: pedal offset and visibility. The Honda NSX was the world’s most practical supercar to date and the F1 project team lowered the scuttle even lower by packaging the air-con in the front – making the F1 very easy to see out of.

There’s Jaguar and Lotus DNA in the McLaren F1

Peter Stevens had worked at both Lotus and Jaguar immediately prior to joining the F1 programme. Other specialists from both companies also had an impact at McLaren. A young Steve Randall was responsible for the F1’s suspension. His dad was Jim Randall, the chief engineer at Jaguar. A homologation specialist also joined from Jaguar. Several Lotus employees jumped ship. Barry Lett was a body engineer who had worked on the stillborn Lotus supercar with Stevens, and also the Lotus Carlton. Mark Masters did the brakes on both the F1 and the Lotus Carlton, and Mark Roberts – a good friend of Stevens – moved from Lotus as a technical illustrator.

Suppliers didn’t make much money

The budget was tiny. Murray’s pitch was simple: “we’re going to build the best engineered car in the world and the best driver’s car in the world, can’t tell you a thing about it at all, but if you want to come on board I need all this stuff for free”. Luckily enough suppliers said “I’m in”.

Explain the advanced active aero

Gordon Murray’s ‘fan car’, the BT46B designed during his time with Brabham, was banned from motorsport for its fan-assisted aerodynamics. Free from those regulations, Murray again put the concept to work on the F1. ‘We had a very short, steep diffuser to get under the driveshafts, and we didn’t want the driveshafts to poke through the diffuser,’ says Murray. ‘So I just steepened it and used fans to suck off the boundary layer, so the air still followed the surface. It was fan-assisted ground effect.’ Don’t say you wouldn’t have done the same.

Why are tyres always a nightmare

Both Michelin and Goodyear developed bespoke tyres for the F1, but the timeframe meant the tyre spec was being honed at the same time as the suspension. ‘Although I’d done tyre work before, I had no idea what a huge influence on steering feel the sidewall construction has,’ admits Murray. ‘So we’d just get something right on the geometry and spring and damper rates and then you’d change the tyres and it would get far worse or far better.’ Remember those words the next time you take your F1 to Kwik Fit and get tempted by the Nanyams.

It had space for an engine, but no actual engine for a while

Murray’s Plan A was for the F1 to have a Honda engine. The plans were for either a 4.5-litre V10 or V12. It got to the stage where the F1 was designed with a space for the engine, no-one knowing quite what would fill it. Then, in 1990, Murray walked past the BMW garage after the Hockenheim Formula 1 race, where he spotted engine genius Paul Rosche having an after-hours beer. The rest is history. Bespoke BMW V12, 620+ hp. Not bad.The development timeframe was tiny

Most cars take around four years to develop. Thinking for the F1 started during Murray’s last season in F1, 1989. Soon after, he walked into an empty building and …. then, on 23 December 1992, Murray drove the first McLaren F1 prototype. 3.2 seconds to 60mph. Sub three years from zero to McLaren F1. Damn.

Awesome rear lights. We’re they custom?

The rear lights are pretty exotic. They came from an Italian bus. It was the quickest way to get approved lights.