In this concluding installment of our interview with Trans-Am record-breaker Tom Kendall, we pick up the narrative just after he’s won his first Trans-Am crown and been invited to compete in the International Race of Champions. Then came the downside, and his big leg-smashing GTP crash at Watkins Glen, where his whole life changed. VR Associate Editor John Zimmermann picks up the story.

You began running in GTP with a Spice in ’90 and then joined Jim Miller’s Intrepid team, where you were a regular front-runner before your big accident at Watkins Glen. What caused the crash and can you summarize your injuries and the rehabilitation process you went through?

Kendall: The crash was caused by a broken left rear hub. We had just been going faster and faster and I kept saying, “If you give me more downforce I’ll go faster,” and so they kept extending the splitter and developing the rear wing with new elements and such. So basically, the hub broke and it hit head-on, and crushed pretty much from the mid-thigh down. I broke my right femur, both tibias, both fibulas and both taluses, which are the ankles. My feet escaped, it was all kind of crushed up from the bottom. Some guys broke their heels like that, but my heels didn’t break, the taluses broke. My rehab was an intensive eight months of all day, every day, for eight months. I guess I had the weekends off because the clinic was closed. My surgery was at Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis and the rehab was at an affiliated clinic north of town that was associated with Terry Trammel’s group, with Trammel and Kevin Scheib. Talk about slow. It felt like making no progress, but you look back a month at a time and you were making real progress.

I was in a wheelchair for five months because I’d done both legs, then I was on crutches for five months, and I had a cane for another eight months, but I was back driving after about eight months, even before I was off the crutches. (Scott) Pruett had had his accident, Foyt had had his, so when they came back I was thinking they came back too soon. Based on what happened to me it seemed too soon, so I said I wasn’t going to come back until I was as good as I was before. I was going to drive a Bondurant car and then a Trans-Am car and then the GTP car, and I told myself that until I’m as fast as I was I’m not going to go further. So it was quite a while. Bob Bondurant said I could come and stay as long as I wanted, so I did and got going pretty good. Then I scheduled a Trans-Am test and I was right on the pace and did a GTP test and again, right on the pace, right away, the first test. I was in really good shape because I was doing all this rehab and doing cardio with it, and upper body before the lower body, so I was in phenomenal shape. The only question was could I do a race distance, two hours. We did a test and it was hard, but it was like it was only as hard as it would be after a normal offseason where you’re getting back in driving shape. So I showed up at Miami, looking like I was doing what I swore I wouldn’t do, which was getting into the car off of crutches. I was quickest in the first session, but it kind of went downhill from there because everybody else—the new Jag had come, the new Toyota had come—had kind of leapfrogged us.[pullquote]

“After the race I called my Mom, because she had watched, and asked, “So what did you think?’ She goes, ‘You sounded really good, but you looked pale.’ I said, ‘You have no idea, Mom.’”

[/pullquote]

Jim Miller was really good about it all. He came to visit me in the hospital and he’s a man of few words and no bullshit. He just said, “Whenever you’re ready, we’re here, and we’ll pick up where we left off. No rush, as long as it takes.” Which was refreshing, but then the deal changed on him, where Chevy pulled back before that next season, but he said, “I told you we’d run, and I’ll fund it all out of my pocket.” I told him that was the nicest thing anyone had ever done for me, but that’s not your job, Chevy should be paying for this, so I said let’s run the number of races they guaranteed, but he said, “I told you I’d do it and I will.” There aren’t a lot of guys like him.

Nobody said anything, but I think there was a definite change in tone from Chevy, up until that point it had been whatever I wanted to do, as long as they were going to do something like that, Herb (Fishel) would move mountains and make it happen. Then all of a sudden, in the middle of ’92, they were not going to do GTP and so I was saying, “Let’s go back to Trans-Am,” but everything I would propose was, “Well, we can’t do that….” To their credit, I think they were going to keep me on as a spokesperson and maybe run a couple of Cup road races, but there was no full-time program.

How did you get hooked up with Jack Roush for ’93?

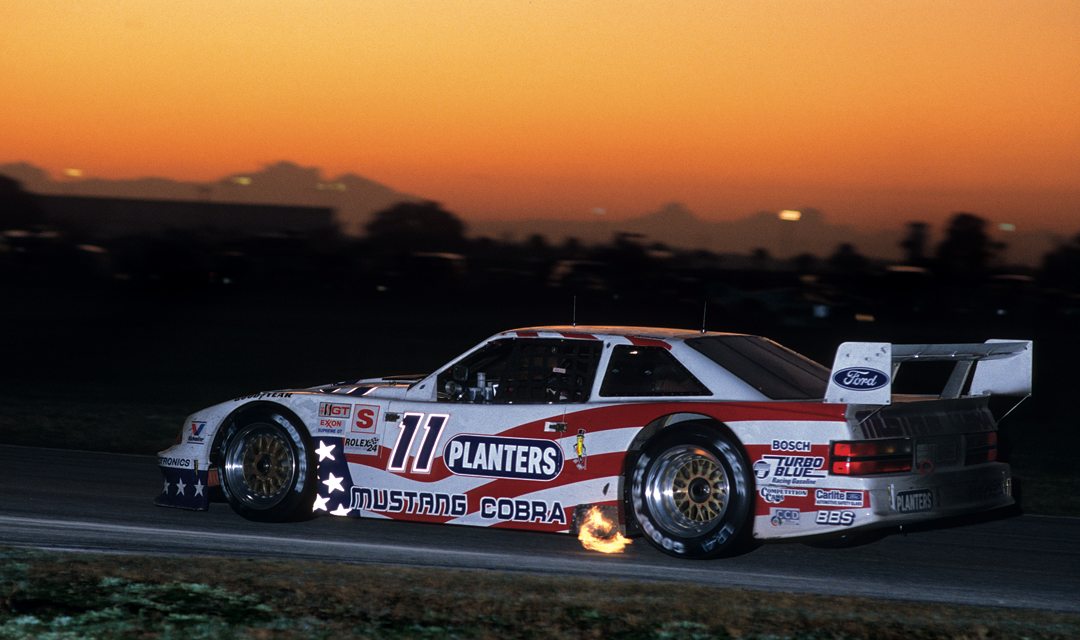

Photo: Hal Crocker

Kendall: Once I had won my first Trans-Ams, Lee Morse from Ford came around and said, “Hey, we’d like to talk to you,” but I just didn’t listen, I told him I don’t like playing one against the other, and after a couple of times I said, “I’m going to stay here as long as they’ll have me.” So he said, “Let us know if that ever changes.” So when that changed and I got the “let’s be friends” call from Chevy, I called and I didn’t know it, but Roush was gearing up for a new Mustang (IMSA) GTS program. I think (team manager) Lee White had just left, so Max Jones was in charge and I called him and he said, “We’re doing this program, let me talk to Jack.” So he did and Jack basically just asked, “Is he OK after his accident?” And Max said yes. The best indication he’d had of that was I had run a third Rocketsports Oldsmobile at Lime Rock because they were in a battle with Nissan for the championship and I brought (Dan) Binks in with me and we kind of led the charge that weekend in a car that probably wasn’t as good as their other two cars, so that removed any doubts. So I signed up with Roush. It’s funny how things work. We won the first race out of the box at Daytona in the GTS car, and it was almost right away that there were overtures from Chevy. It was never direct, but this guy who was a friend of mine was friends with Herb and friends with (GM executive) Jim Perkins, and so midway through that first year I told him the same thing I told Lee Morse: “I will stay here as long as they’ll have me.”

With Jack you won three more Trans-Am crowns, including that incredible 11-race win streak in ’97. What can you tell us about that—and how did you lose to Mike Borkowski?

Kendall: (Laughs) You’re gonna stir up old emotions! The funny thing is that ’97 was the only year we didn’t build a new car. In ’94 we got pretty handily beaten. Buzz McCall’s AER team with Ron Fellows had built a new car and we got kind of caught with our pants down. We built a new car for ’95, but it wasn’t a big enough leap compared to what they did, so we really went to town on our ’96 car. We won four races and repeated as champions and then just honed that car for ’97.

As for how Borkowski beat me, it’s a pretty darn good story. As the streak went on we had sneak attack inspections at the shop, they’d call us seven or eight races in, “Hey we want to come and inspect the car at the shop.” OK, when? “Right now, we’re here!” And they’d walk in. They were getting heat from everywhere, but the tech guys were kind of on our side, saying, “Look, guys, we’ve looked at that thing from every angle. No car’s ever been looked at as much as that car, and there’s nothing there.” It kind of took on a life of its own. Then we tied (the consecutive win record of Mark) Donohue and then we beat Donohue, all of a sudden Trans-Am was getting national attention in USA Today, so it was becoming “Anybody but Kendall.” When we got to Pikes Peak (International Raceway), that morning they introduced all these new driving rules out of the blue at the drivers meeting. They said that front-to-rear contact was allowed, like short-track racing. “You can unstick guys, but you can’t spin a guy out. If you spin him out, you’re gonna get a stop-and-go.” There had been contact in the series, but it had always been frowned upon, so this was something new. So I asked about side-to-side and what constituted side-to-side, and they didn’t have an answer. They finally said, “just next to him.”

On the first lap I get spun out by Dorsey (Schroeder), the only thing you’re not allowed to do, so I’m thinking, he’s going to get penalized. Dorsey didn’t get penalized. I got going again pretty quickly, but I’m last. So I set about picking my way through the field and Borkowski had made it to the front and was driving the race of his life. He was fast, he was tidy and he was really quick down the straightaway and onto the oval. We were quicker through the infield and under braking, so I started hitting him within the new rules. Coming onto the front straightaway I’d do it. I’d never done that stuff before, so I was getting used to it, but I could not rattle him, couldn’t get by him. I literally did that for the last 15 laps, but I couldn’t get next to him. Finally, I see this shaping up on the last lap, and he goes a bit conservative, doesn’t pass the guy ahead and he leaves me almost enough room on the inside, so I go up onto the curb and I’m next to him. I felt kind of bad about it, but these are the new rules, so I start banging him. First, they didn’t enforce the one on the first lap with Dorsey, and now I haven’t spun him out, just following the rules. So basically I just door-slammed him and ran him out of room on the exit. I had three corners to go, but hadn’t figured on the backmarker who was just like idling almost in the next horseshoe, so I know what’s coming. I see Borkowski in the dirt and I see him flat-out and I’m following this guy through the horseshoe, and BOOM! The only thing you’re not allowed to do, spin him out! After the race I’m thinking if they enforce the rules as instructed, then they’re going to move him behind me because he spun me out on the last lap. Regardless of what you think about it, I raced to the rules and put him off so I was pretty sure they were going to reverse it, but they didn’t. They got what they wanted. Like all racers, we only see things from our perspective, but to this day I do feel strongly that I followed the rules and so, according to the rules…. In hindsight, I had many people tell me, including my brother, “That was the best race ever.” And, they got rid of those rules the next weekend. Once I got a little distance from it, I understood the streak was going to end somewhere, so things have a way of working out.

Can you discuss your efforts to do Indycars? Was it just a case of being too tall?

Kendall: Not just, I don’t think. Somebody asked me on Facebook why I never raced Indycars, and the short answer is because I could never convince an owner to hire me, basically, with all that entails. If I’d had a huge budget behind me, they’d have made it work. If I were shorter, I maybe would have gotten some tests, whether that would have led to it or not…. The height was an issue because the effort required to get me into a car was a huge undertaking, and so, all things considered…. I was knocking on the door with Chevy, because at that time, and before I got hurt, I was Herb’s guy. They arranged a test. I drove Bobby Rahal’s Galles/Kraco car with Barry Green, at the end of the ’90 season, before the GTP season. I think there was a push—in ’90 I got that test, I also ran four Cup races with Earnhardt’s team—so there was a multi-pronged effort, I was going into GTP, and Chevy was the dominant engine in Indycars at the time, but then my accident changed all that and I was back to ground zero. I got a little ways down the road with Rahal when he was retiring, but not as far as I thought I did, and then also with Honda, with Team KOOL Green the year it was founded. I went to Team KOOL Green for a fitting and it was a real tight fit. The car was much bigger than the ’90 car that I drove, but after my accident I needed even more room because I had less flexibility in my ankle. Basically my ankles don’t bend, so I have to move my whole leg, and there just wasn’t enough room. Short answer is I just could never get it together. That was the irony when Trans-Am faltered, because I had stopped trying to get anywhere else and was happy where I was. I would have been happy running Trans-Am for another 10 years, but then first Dodge pulled out and then Chevy pulled out and then Ford pulled out.

Who were the toughest competitors you faced during your career?

Kendall: The one guy who was probably the most complete was Ron Fellows. Pruett was really tough, but I didn’t race that much against him. Pruett was fast, but Fellows was faster than Pruett, but Pruett made NO mistakes. He was really aggressive on blocking, and tactically he was just rock solid, and would never, ever give it away. Fellows kept getting better so that in the end there was no weak link. He was the consummate pro. Darin Brassfield was another guy. On race day he might be as good as anybody I ever raced with. He was a little bit like Al Jr., I think he just wasn’t that interested in practice and qualifying, but raceday Brassfield was as good as they come. There’s a lot of good guys, Dorsey, on his day, was really, really hard to beat.

How did you first get involved with television?

Kendall: During the ’97 season when I had the win streak going, Steve Beim was the director for Indycar coverage at the time, and I think they guy who usually did the production was off doing maybe World Cup, and so Beim got put in the producer’s chair, and he wanted to bring me in. He called me and said, “I wanted to see if you were interested in doing the Indycar broadcast from Elkhart Lake next week.” I said I didn’t think I could do that and he asked, “Why not? You race on Saturday.” I said I know, and he said, “Well, why can’t you do it?” I said because of Siebkens on Saturday night. We had just broken Donohue’s record, so it will either be 10 in a row after that race, or it’ll be over. Either way, and it’s Elkhart Lake. Back then, in the ’80s and early ’90s, the only time I drank all year was at Siebkins. By ’97, I don’t think it was the only place I drank, but he goes, “Are you serious?” And I said, yeah, I’m just being frank, I don’t know. He says, “I think you’ve got your priorities screwed up. I thought you’d jump at this.” I said, “No, I’d like to do it, I just don’t know what to say.” So he’s like, “How about if you don’t have to be there very early?” And I said, well, now you’re talking. So that was basically what happened, and he agreed. That year at Siebkins was like no other, and I had promised the night before, when they were trying to get me to take a shot of Jaeger and I said, “No, the race is tomorrow. Tomorrow night I’ll drink a yard of Jaegermeister.” That was a foolish statement. So Saturday night after winning, I was just barely on the sidewalk outside and somebody says, “They’re waiting for you!” I didn’t drink a yard, but did do a half-yard, and I now know that that’s a full bottle of Jaeger. And we refilled it twice! I don’t like feeling bad and getting sick, so the whole time I’m doing shots I’m usually trying to dish, to share with those around me. I was pouring for everyone else, and then we refilled it and I’m pouring some more. A lot of it got in me, and someone drove me home and the next morning I overslept and was late to my first-ever production meeting. I walked in with my hair all over the place, and said, “I’m sorry, but I did try to warn you.” Then I went back to the hotel to shower because I hadn’t showered or shaved, and I got stuck in traffic coming back and almost missed the start. There was a rain delay that year, so instead of the normal five-minute introduction, we had to do a 90-minute fill. And I’d never done that before, and I wasn’t feeling real well, but I just went ahead because I didn’t care. I’ve always had a feel for what’s needed for the job. Like when I came into racing there was no such thing as a clean-cut articulate driver. Well, fast-forward 10 years later and too many are like that. So I think I was ahead of the game because people were ready for straight talk. Straight talk that was considered sort of risqué back then was so tame by today’s standards, but back then just calling people out for stuff was just not done. I had a sense that people were ready for that and I did some of that in that race, and people responded well to it. After the race I called my Mom, because she had watched, and asked her, “So what did you think, Mom?” She goes, “You sounded really good, but you looked pale.” I said, “You have no idea, Mom.”

The hard part going forward, once I started doing more of it, and actually liked it, was not to let the realities of it—that some of the people I was talking about could get me fired—get in the way. So I tried to ignore that because I was working for the fans. My mantra became: “Try to get fired a little bit today,” just as a way to turn it loose and be honest. So, like everything I have done, my whole TV career was accidental, and pretty much everything that followed was accidental, I’ve never pursued any jobs.

I understand you’re getting going in vintage racing now, what can you tell us about that?

Kendall: I haven’t done it yet, other than a race back in ’97, actually. It’s funny, because when I was driving I really didn’t have much interest, and then about four or five years ago it was, “Oh, wow!” First, some of my cars are now 30 years old, and the thought of going out just for fun and driving and doing it on your own schedule—I have four of my cars, from my first five championships, I own those cars—the RX-7, a GTU Beretta, a Trans-Am Beretta, and the Firehawk Nissan 300ZX Turbo that Max Jones and I drove. The three non-Showroom Stock cars are perfect vintage cars, and there’s even some guys running Firehawk cars. I’m not sure it would be that thrilling—they had no brakes. The catalyst was that where I was storing them, at my Dad’s building down in Vista (California), a piece of a building that was just storage, and he said, “At some point that tenant’s going to want the rest of that building….” So I talked to Binks and he said he could store them back in Michigan, so he found a little shop and I ended up sending him eight cars, four racecars and four street cars, some of which are not worth what I paid to ship them back there. So I’m chipping away at it. I’m going to try to get the RX-7 going, and one of the cool things is that three of the cars, the Mazda, the Nissan and the Trans-Am Beretta, are all exactly as they came off the track. All this time I’ve been thinking that I needed to restore the RX-7 because the thing is totally beat, but in recent years there’s been an appreciation for cars as raced, original cars. First, it’s cool, and second, it’s cheaper, because I don’t have to strip it to the bare frame and make everything perfect again. So the RX-7 I have tabbed to get ready for next year, to have it running and race it next year for the first time. The Trans-Am car is the coolest of the bunch, but I’m wondering what it will be like to drive the RX-7 again, a worn-out unibody car that has six seasons on it, that has 330 horsepower, so a car that has all that horsepower and no torque, what will that be like to race? The Trans-Am Beretta will be fun, that’s why the class is so popular. I’m looking forward to it.