1972 Giannini Gruppo 2 Corse

The story of Giannini is the tale of the Italian car tuners, the specialists who took many of the big manufacturers’ road-going products and changed them, modified them, raced them, sold them, and supplied accessories for them. Abarth was one of the great “tuners,” however Giannini, for a long period in Italian racing, was just as competitive. For many, the Giannini story may come as a surprise, in part, because it was founded as early as 1920, but also due to the fact that it is still producing cars, with modified versions of the very latest FIATs. For Giannini, and in fact most of the specialty Italian tuners, the inexpensive small cars made by FIAT have lent themselves well to the whole process of ingenious improvement and development.

The Gruppo 2 Corse featured in this account is just one of a long line of machines which came from the fertile minds of Attilio and Domenico Giannini and is often mistaken for the more widely known Abarth versions of the FIAT 500, 600 and 850. Gianninis were fundamentally Italian – built for the national market and competition scene with a few extravagant excursions outside the country.

Background

The Giannini brothers started up their tuning business in 1920, in the Northeast section of Rome, where they also had an Itala dealership. Most of the FIAT tuning work consisted of converting FIATs to twin-overhead camshafts. After the second world war, Attilio Giannini went into partnership with Berardo Taraschi and together they produced a new Italian car called the Giaur, the Gia coming from Giannini and the ur from Urania, the name of Taraschi’s previous car. The company was based at Teramo, and many successes in Italian national sports car races from 1950 to 1955 were the result of combining the power of Giannini-developed overhead valve engines in a very lightweight chassis.

Giannini started with the basic FIAT engine, which he modified considerably, improving both power and reliability (attributes that would become the company’s hallmark). Taraschi was an accomplished driver and won many events, including taking class wins four years in a row at the Mille Miglia. Most Giaurs were single-seaters and the sports cars were simply widened ladder-frame chassis with modified FIAT suspension and cycle wings.

Giannini had gained the bulk of his FIAT tuning experience before the war when the FIAT 500A engine appeared in 1936 in the now famous Topolino. According to Giannini authority Peter Collins, “Giannini had added a third bearing and alloy connecting rods to the little engine, fitting this unit into a super-light frame clothed in an aerodynamic body and ran the resulting car at Monza where, in 1938, they established 12 new world records.” It was a version of this engine, the G1, which Giannini took to his partnership with Taraschi. The G1 was a 661 cc. 4-cylinder engine with sohc that was later enlarged to 750 cc. In the mid-1950s, he developed the G2, a 750 cc. engine with twin-overhead camshafts and a supercharger; this could produce 115 horsepower, a staggering figure considering the modest origins of the block.

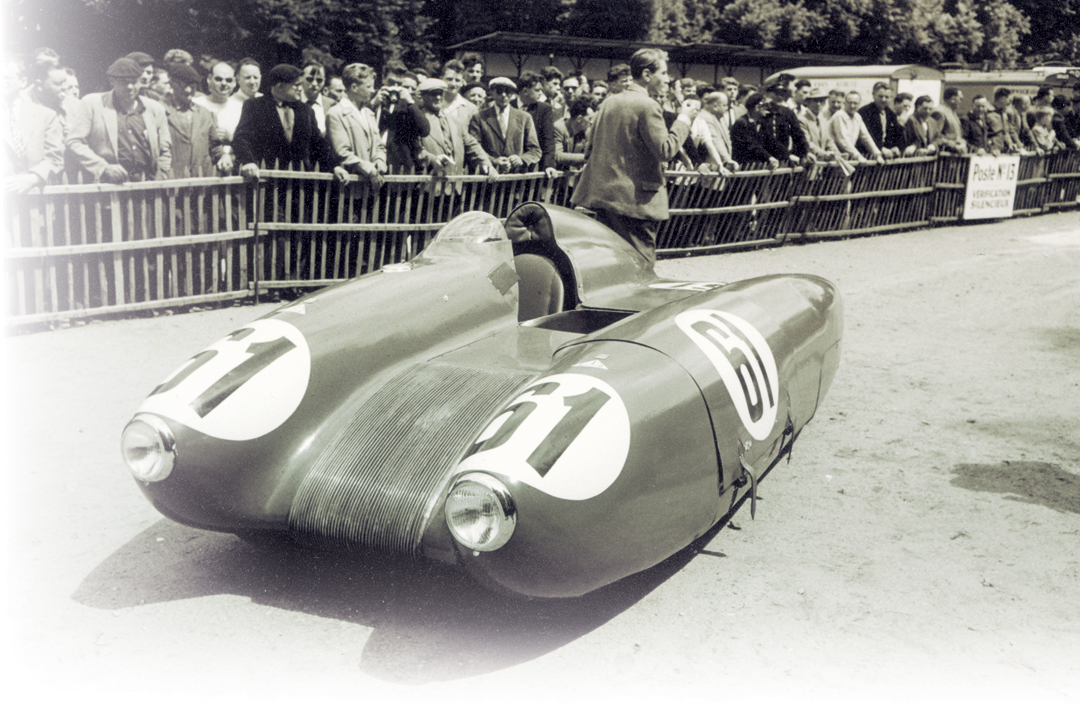

The most eccentric use of this engine was part of a Giannini-Giaur-Nardi project known as the Nardi Bisiluro Giannini, which ran at Le Mans in the fateful race of 1955. This was a twin-boom racer with fairly basic chassis tubes connecting the engine side of the car with the other half that carried the driver. The car received massive attention at the race. However, it was to the great relief of the drivers that it was actually blown off the road by a passing high-speed D-type Jaguar – such was the unstable nature of its aerodynamics and the inherent lightweight of the design. The failure of this rather spectacular car was overshadowed by the crash of Pierre Levegh, which killed more than 80 spectators.

In the later 1950s, Giannini split with Taraschi and continued his development of the G2 engine, which appeared in a Lotus 23 sports car in 1-liter form, and also developed a version for Formula 2 racing. Giannini had been involved in Giaur’s attempt to enter Grand Prix racing when the mid-1950s rules allowed either 2500 cc. unsupercharged engines or 750 cc. supercharged power plants. Only Giaur and Panhard were thought to have wanted to go in this latter direction, although recently a one-off Formula Jr. PLW has emerged in England with some claims that it too was originally designed for the supercharged specification. None of these supercharged designs were successful, though the Giaur F1 actually appeared at the Rome Grand Prix in 1954 in Taraschi’s hands, qualifying near the back of the grid and suffering an engine failure after 5 laps. In spite of the presence of Ferrari 500s and 625s, the Lancia D-50 and several Maserati 250Fs, it was the strange little FIAT-powered device which attracted so much attention.

It was the introduction of the FIAT Nuova 500 in the 1960s which allowed Giannini the greatest scope for success. Whereas the original Topolino 500A engine had been a four-cylinder, water-cooled side-valve unit of some 589 cc. (producing a very modest 13 bhp at 4000 rpm with a gravity feed carburetor), the “new” 500 picked up where the old Topolino motor had left off. This “peoples’ car” utilized a 479 cc. vertical twin – a two-cylinder unit – that was air-cooled. This new engine appeared in 1957 and most of the later racing Gianninis were based on this vertical twin, as it was known, and our featured car is one of the descendants of this FIAT variant.

Giannini modified these FIATs in every imaginable manner, producing the 500 Montecarlo, the 590 Vallelunga and the 650 Modena and Imola. The Vallelunga was probably the best known variant (in fact the car continues on as a replica produced in Japan). These models were essentially different in their engine capacity and were named after the circuits where they had become most successful. Many Italian racing drivers got their racing starts with these cars. Some went on to greater things, while others just carried on in this class of national racing, engaging in momentous battles with their Abarth rivals.

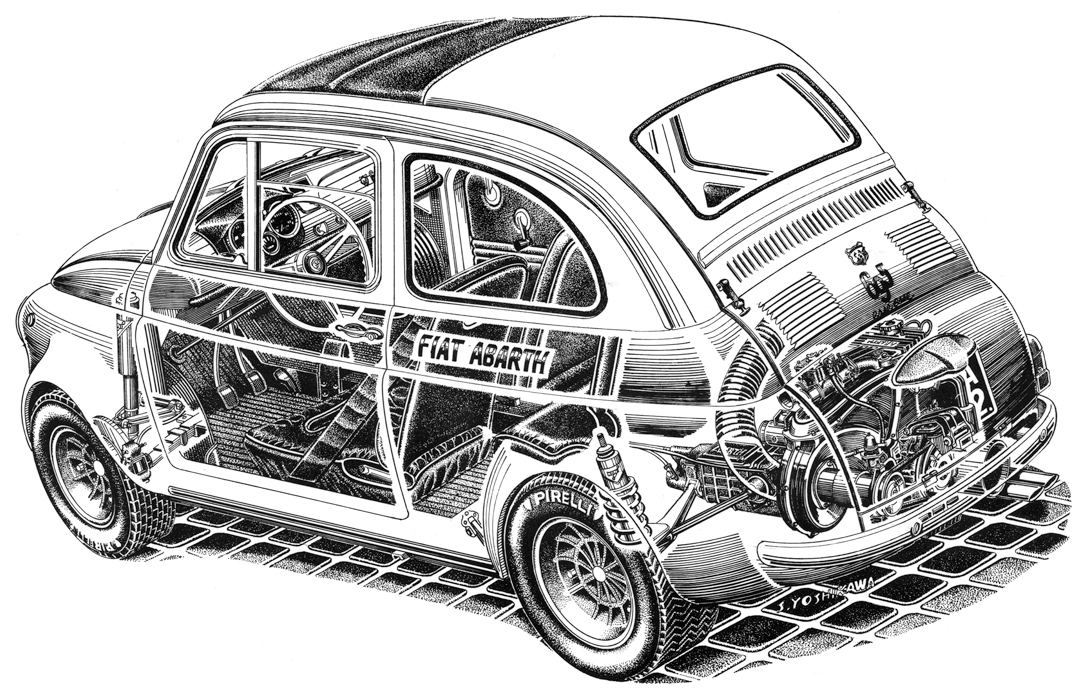

The Gruppo 2 Corse was in direct competition with the vast number of Abarth-tuned FIATs in the Italian Group 2 saloon car championships, both on circuits and on the hillclimbs, which were immensely popular in Italy and throughout Europe at the time. As Group 2 regulations were fairly restrictive, the Giannini and Abarth versions shared much from the original FIATs, particularly the basic suspension which incorporated an independent front setup with transverse leaf springs and wishbones and the use of telescopic shock absorbers. The rear was also independent with semi-trailing arms in FIAT fashion with coil springs and, again, telescopic shock absorbers. One reason Group 2 was so competitive was that the strict rules ensured similar setups based on reasonably priced and available spares. While the engines differed, the FIAT drum brakes were mandatory, as was the use of six-inch wheels. The FIAT close ratio gearbox allowed for some limited modification. The short wheelbase meant that full grids of these potent racers would go bobbing unsteadily into the first corner in one great buzzing horde. It was good racing.

The potent Giannini took no less than 16 class championships during the 1960s and 1970s. Ultimately, it was a rule change, introduced by the FIA, insisting on the homologation of 5000 cars for international racing that effectively killed off the work of Giannini and the small volume tuners in important racing series. This was a sad blow, as the modest changes to the original parts allowed in Group 2 maintained a very stable racing formula for many years.

From this point, Giannini concentrated almost entirely on the tuning and modification of the whole range of FIAT cars, up to the current models. There was a short return to racing in the early 1980s when an 1800 cc. turbocharged motor, which claimed some 500 horsepower, appeared in an Italian Alba chassis in World Championship Group C2 racing. In the hands of Finotto and Facetti it managed to win the C2 class in 1983 and 1984. A previous attempt to build a road-going sports car in the early 1970s, the Sirio, had not been a success, however. The company is currently engaged in producing the Topline and Sportline versions of the FIAT Seicento and Bravo GT.

Driving the Giannini Gruppo 2 Corse

Photo: Peter Collins

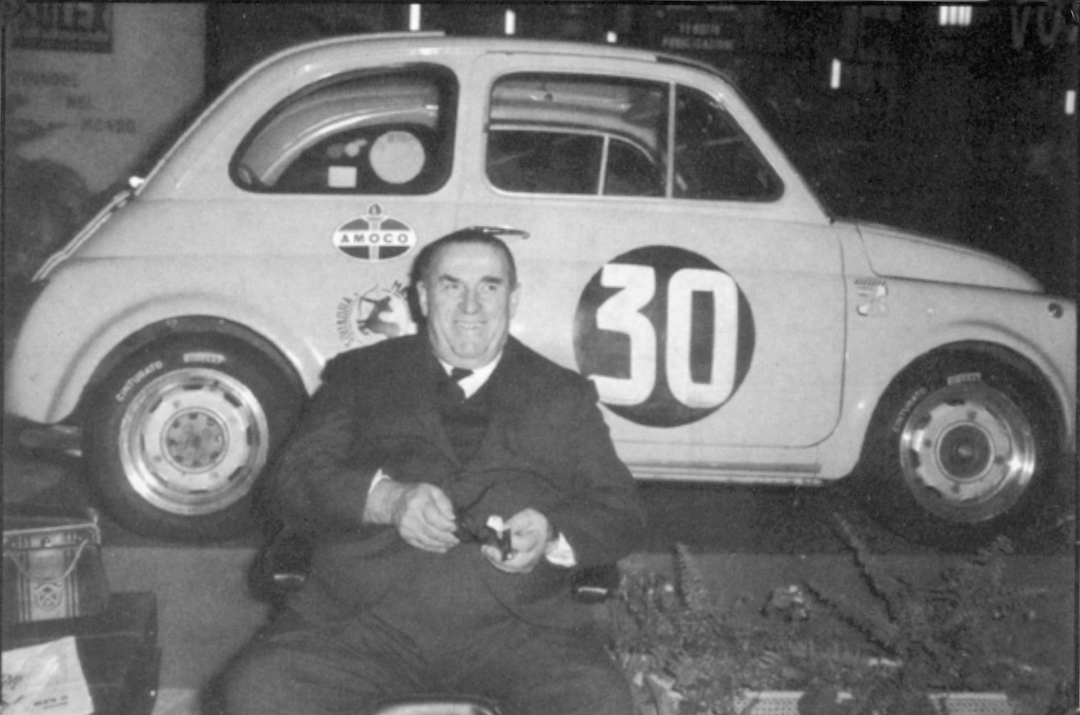

Our test car was produced in 1972 and sold to a Signor Salvatore Carleo, who took delivery in March 1972. It was registered for the road in Salerno, though how much it was ever used as a “stradale” is not known. The exact number of the Group 2 cars produced is also not known, although at times there were more than 15 on the grid at circuit races like Vallelunga. So prevalent were these little cars that even Luca di Montezemolo was one of the pilots of the tiny Giannini saloon racers. How the Ferrari president reconciles his activities in the diminutive Giannini with his career with the Maranello legend is a matter for some speculation! Nevertheless, as we have said, a number of prominent drivers began in little saloons.

Carleo entered chassis number 110F, with engine number 110F000 (the engine still in the car) for major hillclimbs including the Cronoscalata Di Montevergine in 1973, 1974 and 1975. It came second in the 1973 Coppa Della Primavera and won that event in 1975. The car ran in Gruppo 2 Turismo Speciale/Class 500, which included subdivisions for cars of 500, 600 and 700 cc. capacities. The Corse designation meant that this was a highly modified road car, which had several additional features to make it suitable for competition, though the power and handling were fairly similar in both. This particular car was campaigned right through the 1970s before going into long-term storage until current owner Mike Kason learned of it.

I’ve always made it fairly clear that I really like small cars, especially small competition cars. I loved the Moretti of the 1950s, and the Renault Alpine 110 (I was even lucky enough to own one for awhile). The FIAT Abarth Zagato 750 was a favorite for many years, and even the tiny road-going FIAT 500s were appealing. It was this kind of appeal that had the Italian tuners sticking big exhausts, racy engines, competition suspensions and loads of go-faster bits onto these abundantly available people’s cars.

When Mike Kason’s beautiful little Giannini made its first appearance at England’s Brooklands in February of this year, it had only just arrived in the country and hadn’t been run in almost 25 years. Numerous incorrect references to a FIAT-Abarth were overheard, as hardly anyone outside Italy knows about Gianninis. But this is no FIAT-Abarth copy, as evidenced by the carefully constructed 652 cc. Giannini engine rather than the 695 cc. unit employed by Carlo Abarth. According to Kason, there were some things wrong with or missing from the car. It had an original road version’s dash, not the Corse’s, and the seats were not competition seats.

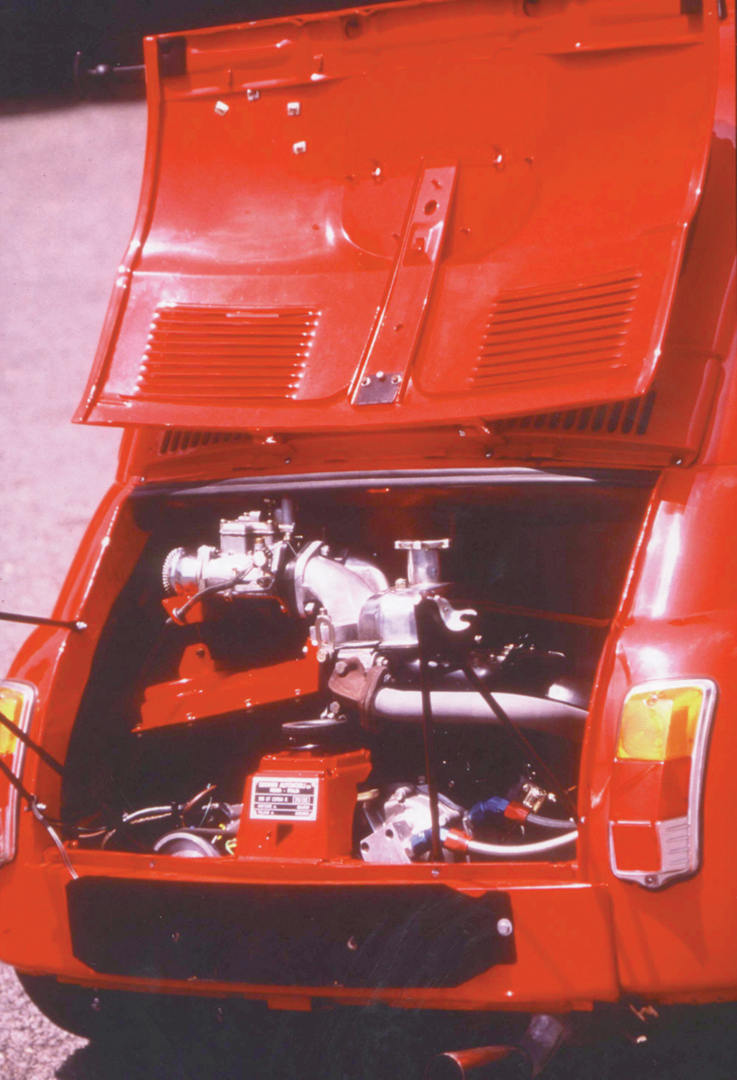

However, the car had its original sign writing and decals intact from the mid-1970s and even the scrutineering tags were still present. The car remained on the original 6” x 10” spun alloy wheels. The permanently raised boot-lid, of course, draws the onlookers into the wonders of the crowded engine compartment with its Adolfo and Alquati-designed after-market add-ons. The exhaust, however, frightens them off when it booms sharply into life, belying the small dimensions of that high-revving, vertical twin, two-cylinder engine with a big Weber carburetor.

Mike Kason is a generous sort of a chap, the kind of person who gets called “larger than life,” which he is in more ways than one. Although the little car was in original spec, he still brought it along for the Brooklands motorsport weekend and was keen to show off his find. While this was, and is, primarily a hillclimb car, with ultra low gear ratios, Mike wanted me to try it out on the Brooklands airfield circuit. Little had been done to the car since its extended period of hibernation, so I was to drive something straight out of the mid-’70s. Kason is very proud of having found such an original treasure intact, even though his background also includes substantially modified and potent dragsters and “funny cars.”

Illustration: Shin Yoshikawa

The Giannini has amazing presence for such a tiny racing machine, and even the problems inherent in a long stationary racer became part of the fun of unravelling it. There was a clutch rather reluctant to engage, and soggy brakes, which wouldn’t do much at all, and a nice sticking throttle to make the whole thing a bit precarious. But once that little engine got revving, and the heart of the car burst into life, everything else faded into the background. With such low gearing for hillclimbs, the rev limit of 7000 rpm was being reached in no time, and I spent several laps trying to cope with the multiple tasks of shifting with an “occasional” clutch, slowing down sufficiently when the brakes didn’t work, pulling the throttle up by hand, and watching the rev counter!!

In an attempt to recreate the car’s past, we made several passes along Brooklands revered and “Monza-like” banking. This is pretty scary in a car of its size, especially with a passenger on board who is operating a troublesome accelerator pedal with his hand! Though flying round the top of the banking was great fun, it felt like we’d tip over any minute as the car bounced heavily over the old circuit’s many bumps and ruts.

Lest it sound like I’m complaining, this was all part of the little car’s charm. With some help from JS Motorsports, the car got well sorted over the two-day event and I managed to have some hard runs with everything working. The Giannini flies off the line in first gear, an amazing sensation in a car with a very short wheelbase, and builds up speed almost before you can react. The tight turns are taken with minimal braking… just a touch and then let the back hang out and use the throttle to power through the corners. With the rear engine stuck so far back in the car and the elevated boot-lid (which was originally designed to aid cooling), it’s quite easy to get distracted by the sight of that end of the car coming around in the bends… that’s how short the car is!

There wasn’t much time to take in the “features,” but it was all pretty much standard FIAT. The car still had its road-going seat belts, which we abandoned as not being very useful. The original FIAT instruments were still there, and these are sparse, to which a more recent rev counter had been added. I had the sensation of having the car wrapped around me as I sat in it – it’s that small. When the crisp 80 bhp are deployed, you fly forward at an impressive rate. 7500 rpm came up so quickly that I had to back off and go for top gear in a big hurry. The short wheelbase has you sliding around, and the tight turns are taken flat so none of the power and momentum are lost. The sensation of that grunting lump behind you is very obvious and attention must be paid to throttle use so the engine doesn’t end up in front!

Photo: Peter Collins

One of the problems in testing a car like this is that just when you begin to get the hang of it, it’s all over. It was our good fortune to have a second try with the Giannini later in the year, as Mike Kason took it all the way to Italy for the Silver Flag hillclimb, only for the engine to let go due to some poor fuel and other teething gremlins. A lot of work had been done to the interior, which had been tidied up, a proper racing seat added, and the suspension had been overhauled. The engine breakage was just the right excuse to really do some work on that bit of the Giannini, so when my third chance came in July, new cams and a lot of careful engine work resulted in an even more potent hillclimb contender.

This time everything worked to perfection, and that meant the rev limit was reached even more quickly, and the brakes were slightly more relevant as the car was at 90 mph at the end of the short straight. New shock absorbers and brake drums have made the handling at high speed more predictable, and the addition of new racing seat belts meant the driver could feel much more in charge of the hurtling demon. The overall impression is of something very potent with a serious sting in the tail. A knack for sensitive throttle control and feel for what the back end is doing is essential to stay on the road, never mind being competitive.

Owning a Giannini

The big question is…where have they all gone? Two more similar cars showed up for the Silver Flag hillclimb, but just how many still exist is something of a mystery, and remains so because the cars are just not that well known and therefore in demand outside Italy. So, most of the survivors must be in Italy, though indeed some did get to the USA. Are there any hiding in US garages?

It is not an easy task to value a Giannini. FIAT-Abarths of similar originality with a competition history get very big money, and there are now lots of FIATs which became “Abarths” sometime later, which helps to cloud the issue. A Giannini can probably be bought from anywhere up to £25,000, but this one could be purchased for £18,000 Sterling. Maintenance and running does indeed parallel the Abarth versions of the FIAT, and upkeep depends on the state of tune and the amount of competition use. Giannini built reliable engines, so if you can find one which has been well put together, it will probably stay together, but they do rev to the limit pretty quickly!

Specifications

Year: 1972

Wheelbase: 7’ 1”

Track: Front: 44.1“. Rear: 44.6“

Overall length: 116.9”

Width: 52”

Unladen weight: 956 lbs.

Suspension: Front: Independent transverse leaf spring with wishbones and telescopic shock absorbers. Rear: Independent with semi-trailing arms, coil springs, telescopic shock absorbers.

Engine: 2-cylinder “vertical twin”

Displacement: 652 cc. (326 cc per cylinder)

Bore and stroke: 66 mm x 70 mm.

Compression ratio: 10.1 to 1

Cam: Giannini Corse Speciale

Con rods and pistons: Ferrari Corse

Carburetion: Single Weber

Induction manifold: Adolfo

Power: 71 brake horsepower.

Gearbox: Close ratio four-speed manual

Brakes: Alloy drums

Wheels: 6” x 10” 3-piece spun aluminium

Tires: Dunlop Sport 165 x 70 x 10

Resources

“Giannini Automobili”

Collins, P.

Auto Italia # 45, May, 2000.

The Encyclopedia of Motorsport

Georgano, G.N (Editor)

1971, Ebury Press, London

ISBN – 7181 0955 0

AZ of Sports Cars Since 1945

Lawrence, M.

1991, Bayview Books, UK

ISBN – 1 870979 23 0

A Record of Grand Prix and Voiturette Racing, Volume 6, 1954-1959

Sheldon, P. and D. Rabagliatti

1987, St. Leonard’s Press, UK

ISBN – 0 9512433 1 4