Sixty-five years ago, Ted Horn became the first driver ever to win three consecutive American National Championships by employing crafty strategy as much as outright speed.

Ted Horn never won the Indy 500, but his ability to finish in the slipstream of those who did remains unequaled in a century of Indi anapolis Motor Speedway history. Consequently, in the three years immediately following World War II, his performances on American racing’s most hallowed ground became cornerstones for a trio of AAA National Championships, won when points were awarded on a per-mile basis, and the 500 was five times as long as any other race on the schedule.

After dropping out of his rookie outing in the Hoosier capital in 1935 when his Miller-Ford’s steering failed, Horn never finished lower than 4th in his next nine 500s.

He recorded what would turn out to be his best Indianapolis result in his sophomore try the next year, rolling home 2nd in Harry Hartz’s supercharged Miller FD6, as Louis Meyer became Indy’s first three-time winner. He then finished 3rd in ’37, again driving for former champion and future official Hartz, before posting consecutive 4th-place finishes in each of ’38, ’39 and ’40, the first of those for Hartz, the next two driving Chicago labor leader Mike Boyle’s Miller FD9. For the 1941 500, Horn drove Art Sparks’ supercharged Adams-Sparks Special, taking another 3rd-place finish in the last 500 run before the outbreak of World War II.

When racing resumed in 1946, most of the cars were survivors from five years before, but Indy had a new owner in Tony Hulman, a businessman from nearby Terre Haute, who found his facility flooded with fans hungry for fresh racing action. Wilbur Shaw had convinced Hulman to save the Speedway from becoming a housing tract, and retired from driving to serve as Speedway president. Thus, when Horn returned to the Boyle team he found himself piloting the maroon Maserati 8CTF that had won for Shaw in 1939 and ’40, but early magneto trouble meant he finished only 3rd. The next May Horn qualified the Maserati—now entered by Boyle’s chief mechanic, Cotton Henning—on the pole, but ran 3rd again, delayed by an oil leak. In ’48 he led 74 laps but finished 4th after slowing to save his engine. It was perhaps Horn’s best chance to win the 500. He would never get another.

Eylard Theodore Horn was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on February 27, 1910, the son of Armandus and Mary Horn, players with the city’s German Theater. The Horn family lived a nomadic life during Ted’s early years—their theater work disrupted by the outbreak of World War I—ultimately settling in Los Angeles, home of the emergent motion picture industry, as the Roaring Twenties opened. Ted had studied poetry, art and music at private school in Ohio, but despite showing talent for those pursuits he had another passion in mind.

At age 15 he bought an old jalopy, and within a year began racing it at dirt tracks in California. His early efforts proved problematic, however, as while driving Noel Bullock’s Rajo at Banning, Horn locked wheels with another driver and found his way through the fence. Realizing he needed experience, Ted set about learning the lessons of his craft by running small-time stock car races, but when given another chance at legendary Legion Ascot Speedway he ruined the opportunity by taking out a length of the guardrail circling the track.

After his father argued that racing really might not be such a good idea, Ted took a job as a photo engraver’s assistant with the L.A. Times newspaper. By 1931, however, racing’s allure beckoned once more and he wrangled his way into a car called the L&C Special at Legion Ascot. On the second lap, though, it slipped out of his grasp on Ascot’s famous oiled dirt and slid over the rim of the raceway, into a nearby tree. Horn was hospitalized with a broken foot and burns on his back. Once again, his father harried him about quitting, but the now 21-year-old was having none of it.

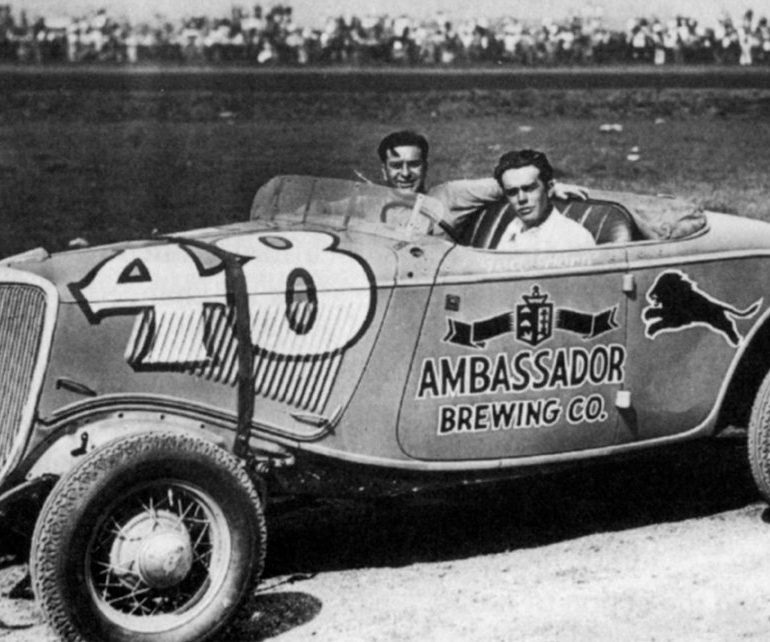

Upon healing he bought the Rajo Special and continued his education by running at the back of the pack. In his spare time he took a job driving a delivery truck for the Los Angeles Eastside Brewery where he met a young Sam Hanks, and his tales of racing exploits fueled Sam’s desire to race himself. On the track, his efforts impressed veteran driver Chet Garner who became his tutor, and as Ted gained experience his results began to improve. He also found a friendly rivalry developing with another newcomer named Rex Mays that would last the rest of his life.

The First Step Toward Fame

Horn’s “breakthrough” race came on Sunday April 15, 1934, in the 150-mile American Targo Florio (yes, Targo) for track roadsters on an approximately 1.5-mile combination circuit using the 5/8-mile Legion Ascot oval and roads in the nearby hills. After qualifying 3rd, the 24-year-old Horn finished a fine 2nd to Indy 500 winner Louis Meyer. The result attracted the attention of the legendary Harry Miller, who recruited him to drive one of the new Miller-Fords he was building in consort with Preston Tucker and the Ford Motor Company for Indianapolis the following year.

Ted had actually gone back East to try Indy in ’34, but was unable to find the speed necessary to qualify. When his rookie ride in Miller’s car also ended dismally in ’35, he feared his racing career might be over. Despite the observations of Ford team captain Peter DePaolo, Miller somehow failed to grasp that he’d located the car’s steering box too close to the engine, so that all four Miller-Ford team cars were forced out by heat-related steering failure. It would be Ted’s only unfinished race at Indy.

Horn’s car had lasted longest because it had been fitted with a prototype box made of steel—rather than the standard bronze—by New Yorker Charles Zumbach, but still it seized. Afterward, the problem was said to have been not so much the heat from the engine as poor heat treatment of the steel parts. Ted’s car’s flathead V8 had also featured a trick, high-rise 180-degree intake manifold for its two Stromberg 97 carburetors that had been designed by Ford engineer Don Sullivan, but it did him no good.

That same year Horn decided to move his racing operation east, setting up Ted Horn Engineering in Paterson, New Jersey’s Gasoline Alley, near the popular racing venue Hinchcliffe Stadium. This allowed him to establish a machine shop so he could design and build his own cars while servicing those of other drivers, notably the legendary Tommy Hinnerschitz, Bob Sall, Rex Records and Walt Ader, who made up the T.H.E. team. The move east was triggered by an overture from powerful promoter Ralph “Pappy” Hankinson and advice from Louis Meyer, both of whom believed Horn would benefit from contesting the East Coast and Midwest circuits where competition was fiercest.

Ted Horn was a very careful, methodical and superstitious young man; a perfect gentleman on and off the racetrack. His trademark fastidiousness meant the presentation of himself, his cars and his crew was always impeccable. These traits would characterize his efforts through the years, setting new standards for the industry, but his lack of success at Indy had left him doubting his career choice.

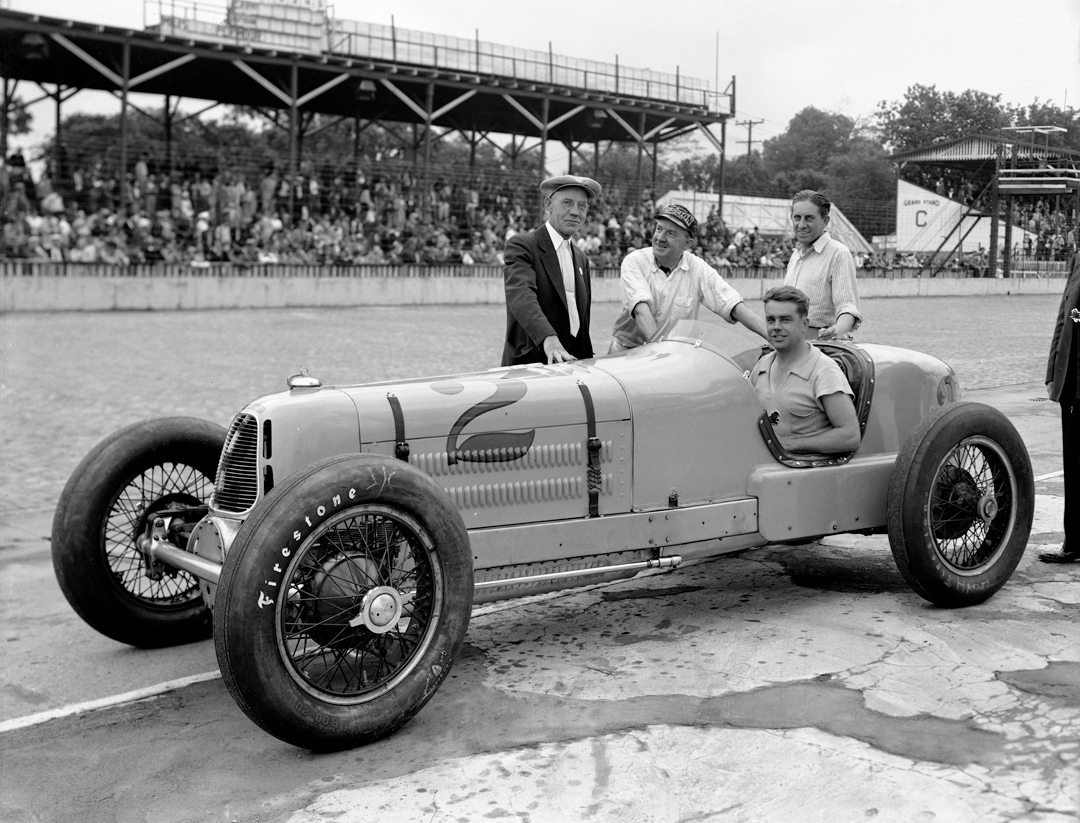

Luckily, board track hero and 1926 AAA National Champion Harry Hartz had been impressed by Horn’s rookie performance in the doomed Miller-Ford, and offered him a ride for ’36. Before Ted could take it though, he crashed his sprint car at Lewistown, Pennsylvania, crushing his right shoulder and collarbone. Even though his recovery had been slow and painful, when May rolled around he returned to Indianapolis ready to climb back into Hartz’s waiting front-drive Miller. By leading 16 laps and finishing 2nd—as the Speedway welcomed its first three-time winner, his old adversary Meyer—Horn cemented his place in the sport.

He drove Hartz’s Miller at Indy again in 1937, trailing only Wilbur Shaw and Ralph Hepburn under the checkered flag as they produced Indy’s closest finish yet. A big crash in September at Nashville all but destroyed his sprint car and sidelined him for several months, but even though the car was rebuilt, the crash inspired Horn to begin building his own “Big Car.” Once fully recovered, he was eager to get back into the Hartz Miller for Indianapolis in ’38, and brought it home 4th behind winner Floyd Roberts, Shaw and Chet Miller.

As he became more and more competitive, Horn realized his personal fitness would be crucial to future success, and implemented a strict regimen of exercise and diet to hone his physical condition, taking special care to avoid tobacco and alcohol.

When everyone arrived at Indianapolis for the month of May in 1939, they found the big old four-cornered Speedway’s legendary bricks had been covered with smooth asphalt paving everywhere but along the front straightaway. Horn had been recruited into Mike Boyle’s operation by crew chief Cotton Henning and, given mentor Hartz’s blessing, lined up as teammate to 1937 500 winner Shaw. Like Hartz, Henning had seen something special in Horn, a kindred spirit dedicated to maximizing every opportunity and doing things “the right way.”

Horn would drive Boyle’s nine-year-old Miller front-drive fitted with a Miller “Big Eight” engine while Shaw got a new Maserati 8CLT. Wilbur would win the 500 for a second time in ’39 and then become Indy’s first back-to-back winner by duplicating the feat in 1940, as Horn finished 4th both years. He’d managed to lead a number of laps in that 1940 race, but when rain clouds settled in over Indy’s backstretch around three-quarter’s distance it brought out a yellow caution flag that never went away. Ted, stranded a lap down, was unable to get back the only race lap he would not complete during those nine incredible years at the Speedway.

In ’41, Horn asked Henning to release him from the Boyle team so he could drive for legendary chief mechanic Art Sparks in one of Art’s “Little Six” machines. He was enthused about the prospect, but the car arrived at the Speedway late, and was also rear-wheel-drive, whereas previously he’d handled a string of front-wheel drivers. Qualifying late, he gridded 28th, but his pace increased in the race as he learned the car’s intricacies and he ultimately finished the 500 miles 3rd.

Following Pearl Harbor, Ted tried to enlist, but was rejected because of the lingering after-effects of his injuries from six years before. During the war T.H.E. did subcontract machine shop work for the war effort while Horn waited for the hostilities to end so he could go racing once again. During this time he hooked up with local mechanic Dick Simonek, and their partnership endured after the war when Simonek prepared the cars that would carry Ted to his National Championship hat trick.

Getting Rolling Again

When the first major Sprint Car race following VJ Day, in August of 1945, was held at Essex Junction, Vermont, Ted and his sprinter were there, clocking the fastest qualifying time before winning both his heat and the Main. He and his T.H.E. team finished off the year with a stirring demonstration of top form that left no doubt Ted was capable of a serious run for the National Championship in 1946.

Old rival Rex Mays had won the crown in both 1940 and ’41 and was, of course, looking to extend his string post-war, but those hopes took a harsh blow at Indy when his Bowes Seal Fast-sponsored Stevens-Winfield dropped out after just 26 laps to be ranked 30th. Horn, welcomed back by Henning and Boyle to drive the Maserati, qualified 7th and finished 3rd despite losing a lot of time—and perhaps his best chance for victory—to a long early stop to change the magneto.

When the Championship Trail rolled into Langhorne, Pennsylvania, for a June 30 date on the “Big Left Turn,” Horn qualified on pole in the 1941 Indy-winning Wetteroth-Offenhauser now owned by his fishing buddy Fred Peters. He led the first 17 laps, but finished 3rd as Mays won. After a two-month summer break, the championship resumed at Lakewood Speedway just south of downtown Atlanta. The one-mile Lakewood oval was constantly plagued by dust as its red Georgia clay surface had been worn out over the years, and it was this dust that wrought lethal havoc once again.

Horn had led 81 laps that afternoon, and was out front with two laps to go when disaster struck on the backstretch. Having led earlier, veteran Billy DeVore was guiding his ailing Wetteroth-Offy around slowly in the low groove, just hoping to make the finish, but when that year’s Indy winner, George Robson, came upon the slowly moving car the dust obscured his vision until it was too late. Swerving hard right to avoid DeVore, Robson’s car—the 1938 Indy winner in Floyd Roberts’ hands—clipped George Barringer’s mount—Wilbur Shaw’s ’37 Indy winner—and spun it around into traffic where it was hit by slowest qualifier Bud Bardowski’s older Sparks Special, fatally fracturing Barringer’s skull.

After tagging Barringer, Robson’s machine bounced back into DeVore’s crippled car—pushing it up an embankment and down the other side into a water-filled ditch—before beginning a series of end-over-end flips that flung the Indy winner out onto the racing surface where he died when struck by several other cars. Race leader Horn arrived on the scene and actually ran over the hood from Bardowski’s car, then stopped and tried to warn other drivers of the incident ahead.

The tragic race was red-flagged and Horn declared the winner, but he would later be disqualified following a protest by runner-up George Connor’s car owner, Ed Walsh. The AAA Contest Board ruled that Horn’s “involvement” in the accident, running over Bardowski’s hood, “thereby prohibited his participation in the awards.” Connor’s win was the first in Indycar competition for a Kurtis chassis.

At the Indiana State Fairgrounds two weeks later, Mays lapped the field from pole position as Horn, slowed by a puncture, finished 4th behind Mauri Rose and Emil Andres. Mays won again from pole the next week in Milwaukee, but Horn was right behind in 2nd.

Prior to October’s season finale at Good Time Park in Goshen, New York, Ted and Rex were scheduled for a match race, but a connecting rod in his Bowes Seal Fast Special broke during practice, eliminating Mays from the feature. Consequently, he drove Andres’ pole-winning car, a 1933 Adams-Offy, in the head-to-head preliminary and won by a foot. Tony Bettenhausen dominated the feature in pal Paul Russo’s Wetteroth-Offy the next day, lapping runner-up Horn and the rest. Although Mays won three races that season while Horn went winless, Ted’s consistency gave him the crown by 100 points over Andres as Rex had to settle for 5th, his early retirement at Indy dooming his championship hopes.

“Ted Horn and Rex Mays are often mentioned in the same sentence as the two best drivers who never won the Indianapolis 500,” commented Donald Davidson, historian at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, “but they were also alike in the way that they represented the sport. Horn was always well dressed; he played the role of the champion very well. He would have a clean uniform, and a clean shirt with his name on it when most people didn’t have uniforms. He always had immaculate equipment and had the clean-cut appearance, the mustache, and apparently was a good spokesman. He made a very fine representative for the sport, and he was a good role model for young people. He just had a presence about him.”

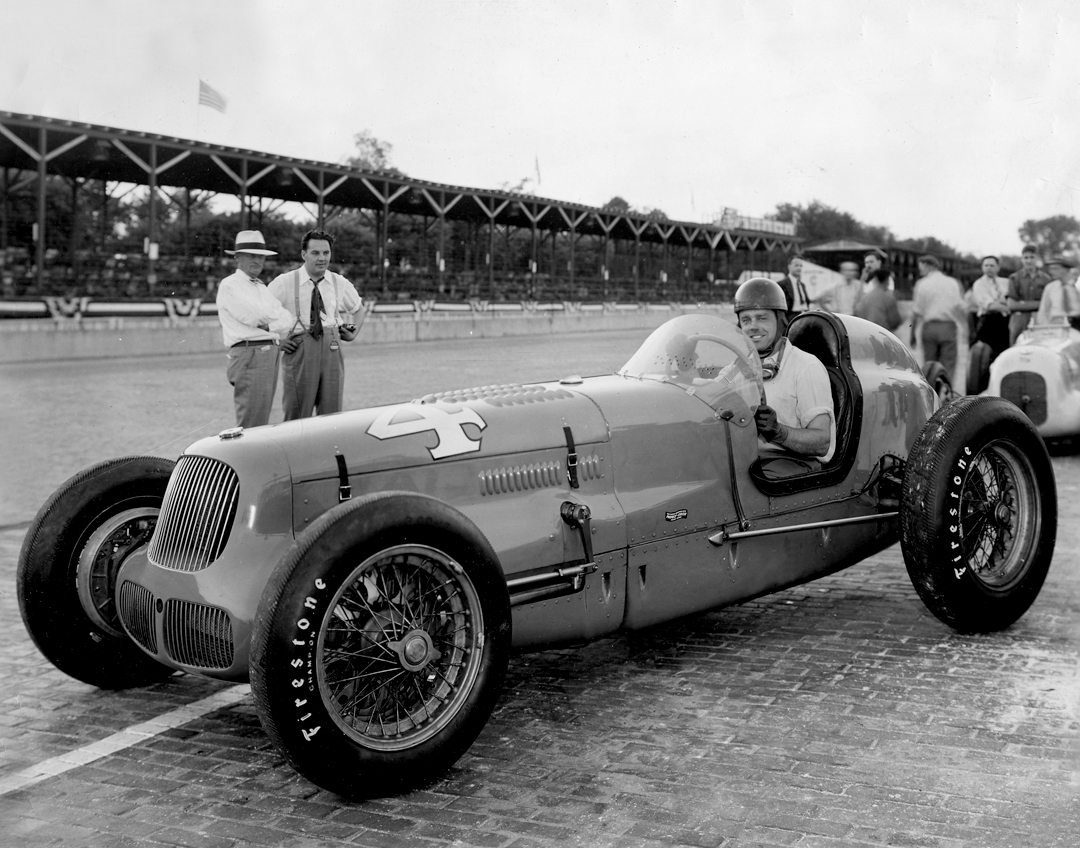

Entitled to wear the champion’s numeral 1 on his cars in ’47, Horn showed he deserved it by putting his ex-Boyle/Shaw Maserati—now owned by Henning, painted sparkling black with glittering gold numbers and backed by the Bennett Brothers, a pair of wildcat oil drillers—on the pole for the season opener at Indy, ahead of the growling Novi of Cliff Bergere and Mauri Rose’s Blue Crown Special. It was false hope once more, however, as an early oil leak cost Ted more time in the pits than his speed on the track could regain and left him 3rd at the end behind the victorious Blue Crown twins Rose and Bill Holland.

Strange as it may seem, Ted Horn had never scored a National Championship win before the summer of 1947, when he won a rain-shortened 90-mile contest at the fairgrounds in Bainbridge, Ohio, by a lap. His mount that day was the self-built Horn-Offy that had debuted the month before at Langhorne after he’d skipped Milwaukee’s usual post-Indy date to get it finished. He would come back to win with it again at Milwaukee during the Wisconsin State Fair in August and then take the season finale in Dallas by three laps to wrap up his second consecutive AAA title. A pair of 2nd-place finishes at Goshen and Springfield added more precious points, so that his final margin over championship runner-up Holland was 310.

Just as the ’47 season had closed at Arlington Downs Raceway in Dallas, so did the ’48 season begin there, with the same result, Ted Horn in Victory Lane—this time three laps ahead of runner-up Duke Dinsmore. It was the first time in 18 years that the opening round of the National Championship did not take place at Indianapolis, so that when Ted arrived at the Speedway for the month of May, the #1 on his Bennett Brothers Maserati identified him not only as the reigning champion, but also the current points leader.

“I think the Indianapolis race will be mine this time,” Horn reportedly told the gathered media as the month began. “I’m getting old, you know, and I need to win it pretty soon.”

Out on the 2.5-mile oval his glistening black Maserati ran with the fastest cars all month, even though he qualified it only 5th. As the race rolled through its early stages he found himself leading, so that when he pitted at the 150-mile mark Mays took over out front. Ted rejoined in 4th but worked his way up to 3rd by 250 miles, and after Mays retired with a cracked fuel tank he held 2nd at 300. During his final pit stop, however, Henning’s sensitive ear detected the engine’s bearings failing and warned Horn he’d better back off to make the finish and score those valuable championship points. He ultimately finished 4th in what would be his last 500.

Horn was just as steady on the Championship Trail as at the Speedway, his metronomic consistency as a points collector always landing him near the top of the standings: 3rd in ’36, 2nd in ’37, 4th in ’38, 3rd in ’39, 4th in ’40, and 2nd in ’41 before his title hat trick. During the six-race 1946 season he went winless but still topped the points, then in ’47 he won three of 11, and in ’48 he would triumph twice.

His run to an unprecedented third consecutive National Championship was interrupted only by throttle problems at Langhorne that took him out after 66 of the 100 laps, but still left him 9th in the results. He finished 3rd in all three races at Milwaukee and won at Springfield before wrapping up the title with another 3rd in the inaugural race on the brand-new one-mile dirt track at DuQuoin, Illinois.

Three races—and the Pikes Peak Hill Climb—remained on the schedule, and Ted believed it was only right for him to finish out the season (though he didn’t go to Colorado). On Labor Day weekend in Atlanta his car’s crankshaft broke after but 15 laps, ending a lengthy streak of consecutive top-10 finishes in Big Car and Sprint Car competition. Two weeks later, however, back at Springfield, he finished 3rd yet again. The season’s final round would be a second outing at DuQuoin, the fully modern “Magic Mile” of Southern Illinois, in mid-October.

A week after Springfield, Ted won a Sprint Car race in Massachusetts, but then, looking to recharge his personal batteries, took his new bride Gerri and his family to Florida for a week at the beach. He may not have wanted to go when the time came to return north for the finale on October 10, but he had given his word.

The Fateful Final Fling

For all his methodical and analytical approach to racing, superstition had always played a large role in Horn’s imagination. A St. Christopher’s medal was always fastened to the dashboards of his cars; he would carry seven “lucky coins” with him; and he stopped shaving before a race, after fellow driver Doc MacKenzie died in Detroit one day having razored off his trademark beard that race morning. He regarded peanuts as unlucky after getting caught up in that nasty Sprint Car crash in Nashville with four other cars after they’d all been sprinkled with peanut shells before the race by an unbelieving crewman; and, of course, there was the color green, long considered bad luck in American racing. Several of these would haunt him at DuQuoin.

First, legend has it that his wife told him she’d packed just two outfits and one had been soiled, leaving only a green dress ready to wear. She knew that the color was among Ted’s many superstitions, but he told her not to worry. Then, he shaved that morning, which he hadn’t done on a race day for a dozen years. Finally, during pre-race practice, AAA tech chief Sol Silbermann asked if he’d had the spindles on his car Magnafluxed recently. Ted told him no, but he’d ordered a new set and reckoned the current ones would last another race or two.

Contrary to his usual smiling, carefree and light-hearted demeanor, it was an apparently troubled man who climbed into the cockpit of the #1 Horn-Offy on the outside of the second row that dreary day in DuQuoin. Wearing new white overalls bearing the embroidered inscription: “Ted Horn National Champion,” he wanted to win, to cap his record-setting season in fine style.

On the second lap of the race, however, the suspect left front spindle snapped, pitching the car into a series of violent flips. The errant machine threw its driver out onto the track before collecting Johnny Mantz’s Agajanian Special and pushing it up against the wall, then continued on depleting its kinetic energy until coming to rest on the edge of the infield grass.

After the race was red-flagged, Horn and the essentially uninjured Mantz were rushed to Marshall-Browning Hospital in town, where Ted was pronounced dead with severe head injuries, a crushed chest and multiple fractures of his left leg. He was 38. Like Jimmy Murphy 24 years before, he would be crowned National Champion posthumously.

More than half a century would elapse before anyone would match his championship hat trick, and then Newman/Haas Racing’s Sebastien Bourdais went him one better, claiming four consecutive Indycar crowns between 2004 and 2007. Over those final three years of his Indycar career Ted Horn drove 25 races, scoring five wins, taking three poles, and logging 17 top-three and 21 top-five finishes. He led laps in 12 of the races and qualified outside the top 10 just once in those 25 starts—truly National Championship-caliber performances.