1958 DKW Monza

There are many unusual and interesting cars in the Lane Motor Museum. Seldom is there a visitor who knows the names of all the cars or has even heard of all of them. One company that is familiar to some is DKW, but the 1958 Monza is a rare and very attractive car that few visitors are likely to have ever seen before. Then there’s the company’s name, Dampf Kraft Wagen, which translates to “steam-driven car.” Steam-driven? Where did that come from? And the model, 3=6, what does that mean? This profile is intended to clear up those questions and introduce a very special DKW.

Dampf Kraft Wagen

DKW was created, in 1916, when two Danes, Jürgen Skafte Rasmussen and a fellow only remembered as “Mathiessen” began experimenting with designs for a steam-powered car, therefore the “Dampf” in the original name. Nothing came of the steam car, but Rasmussen built a small two-stroke engine, essentially a toy, he called Das Knaben Wunsch, or “The Boy’s Wish.” Soon thereafter, in 1919, he put a version of the engine in a motorcycle frame and DKW became a motorcycle manufacturer. Rasmussen still used DKW, but it now stood for Das Kleiner Wunder, or “The Little Wonder.” DKW achieved considerable success with motorcycles, and by late 1920, it was the world’s largest producer of the two-wheeled machines. It was a status that DKW would keep until WWII.

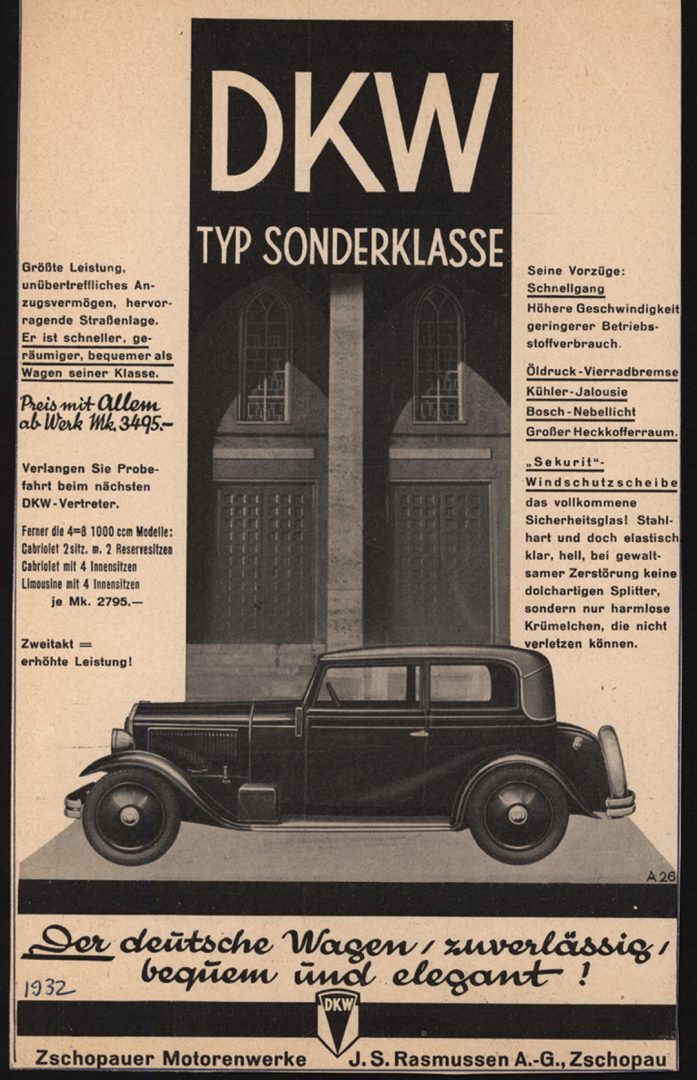

Another significant change for DKW came in 1932 when it joined with Audi, Horch and Wanderer to become Auto Union. DKW continued to produce cars, but the badge was changed to include the four-ring symbol of Auto Union, as well as DKW. It seems that the company’s automobiles initially drew attention because of the unusual technical approach—two-cylinder, two-stroke engines driving the front wheels. In a road test, in the November 1933 issue of the British magazine The Autocar, a four-seat cabriolet received very positive comments: “. . . probably no one could tell that the D.K.W. had not a four-cylinder unit, or even then that it was a two-stroke. . . . Not only is this a car that can meander comfortably and easily by virtue of its size along byways, but also can be driven to put up a quite useful performance on a run of some length, going up willingly, if required, to above 50 mph, and having a maximum appreciably above that which the average user of such a car is likely to need.” DKW had become successful. By 1934, it had taken 15 percent of the German car market and was second only to Opel in sales.

With the country divided after the interruption of production caused by the Second World War, production was restarted in both the East and the West. At the former Audi factory in the East, the old style cars were built under the name IFA F8 using the same pre-war fabric bodies and styling. In West Germany, production was resumed in Dusseldorf. The name Meisterklasse was still used, but the styling was new —the cars were more rounded. The same body style was used for the three-cylinder Sonderklasse. The Meisterklasse lasted until 1954, when it was dropped from production. The Sonderklasse continued and was restyled several times before its demise in 1963.

There were a number of subsequent models, as well as corporate owners of DKW, in the 1960s. Auto Union was absorbed by Mercedes-Benz in 1957 and was subsequently bought by the Volkswagen Group in 1964. The last DKW was the F102, which was a replacement for the Auto Union 1000, but sales were poor because the advantages of two-stroke technology had been overtaken by advances in four-stroke engine design. It was replaced by an Audi F103 using a four-stroke engine. DKW ceased production in 1966.

3 = 6

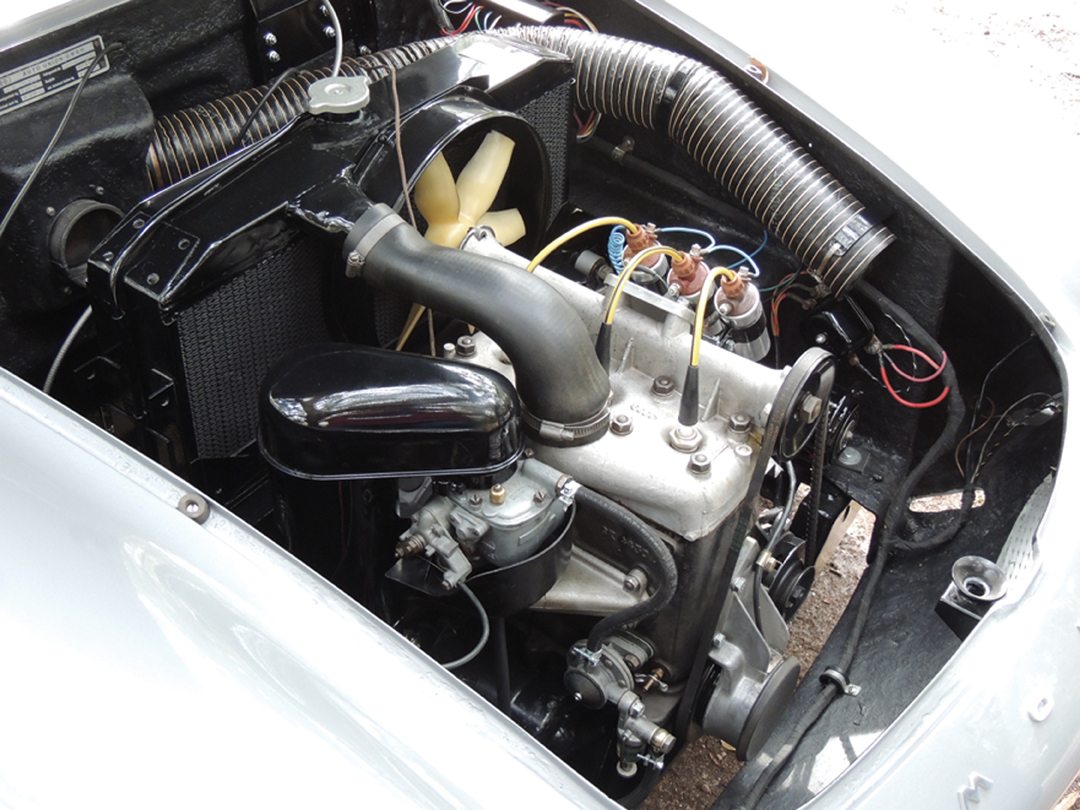

The DKW 3=6 model, also called the Sonder-klasse and, in factory parlance, the F91, was launched at the Frankfurt Motor Show in the spring of 1953. It had a three-cylinder, two-stroke engine and front-wheel drive. The model name, “3=6,” came from one of the characteristics of a two-stroke engine. Unlike a four-stroke engine, the two-stroke produced a power stroke on every revolution of the engine, rather than on every other revolution. The thinking was, therefore, that the three-cylinder was like a six-cylinder. This comparison with a six-cylinder engine suggested that the DKW engine had more power than other engines of similar displacement, although it was actually in torque where the two-stroke engine dominated. The successes that DKW enjoyed in European rallies seems to support the assumption that 3=6. For several years, in the 1950s, DKW was the most successful brand in rallying.

The 3=6 model was produced in several body styles—two and four-door sedans, two-door coupe and cabriolet, and three-door wagon. Despite increasing competition from the Volkswagen Beetle, the DKW was reasonably successful as a result of its variety of body styles, but especially because of its superior interior space. Both manufacturers produced eminently functional automobiles, but they were not the kind of cars that made people turn and watch as they drove past. As memories of WWII faded and industry and economies recovered, people began to look for cars for play, as well as for function.

3=6 Monza

If you wanted a moderately priced German sports car in the mid-1950s, your choice was limited to the Porsche 356. Small coachbuilders saw an opportunity and began making bodies for VW chassis. Dannenhauer & Stauss was showing a VW Cabriolet at a show in Wiesbaden, when Herr Strauss had an opportunity to talk with Günther Ahrens of DKW and Albrecht Mantzel, a DKW tuner, about the possibility of building a sport coupe on a DKW chassis. DKW was interested, and Ahrens provided an F91 chassis. A scale model was sculpted, then a full-size model was built on a shortened chassis. The model was very attractive, with a curved windshield and rear window and a rear that took cues from both the Porsche 356 and Mercedes 300SL. It was decided that the body would be fiberglass so that future changes could be made easily.

The sixth car built had an extra-large fuel tank, was lightened by 650 kilograms (1430 pounds), and was entered in the Le Mans 24-hour race in 1957. It was able to reach speeds of about 140 kph, but it retired with engine problems after 151 of the 327 laps achieved by the winning Jaguar D-Type. The seventh car built was also somewhat modified, and it was one of these two cars that was the reason the cars became known as Monzas.

A total of 15 Monzas were produced by Dannenhauer & Stauss. Dannenhauer & Stauss was a small firm that hand built the cars and was, in the view of DKW management, too small to meet the demand they anticipated as a result of the publicity about the speed records. Fritz Wenk, an Auto Union distributor in Heidelberg, took over production at the Massholder factory. Wenk projected production of 20-25 cars a month, but he faced some opposition from both Massholder, who was not excited by that high a level of production from his factory, and Auto Union, who saw the Monza as a competitor for the Auto Union 1000SP.

Actual production ended up being only five to seven cars a month. Wenk pushed for a second series of cars to be produced at ten or more cars a month, but soon realized that Massholder could not meet that goal.

Wenk was a distributor and depended on sales in order to be profitable. He was also interested in exports, so he looked for a more capable firm than Massholder. Who he found was Robert Shenk and his coachbuilding firm in Stuttgart. Shenk was in a better position, financially and physically, to meet Wenk’s production goals. A number of changes were made to the Monza to make production more efficient, such as molding the upper and lower body as separate units and gluing them together. Shenk Monzas were built with either an 896-cc engine producing almost 40 hp or an 1000-cc engine with 44 hp. They sold for DM9,985 and DM10,450, respectively. Air conditioning was available, as was a 50 hp engine. Exterior and interior color combinations were expanded to suit the various tastes of potential buyers, but in 1958 Auto Union took action to expand 1000SP sales at the expense of the Monza. The price for a new 1000SP was set lower than what was possible for the Monza. Wenk faced the possibility of losing money on every Monza he built and sold, so production was ended in 1960. The total number of 3=6 Monzas built by each manufacturer was:

• Dannenhauer & Stuass: 15

• Massholder: 80-90 (apparently there were

some issues with record keeping)

• Shenk: 124

It must be noted that these numbers still stoke arguments among DKW enthusiasts and the company.

3=6 Monza Robert Shenk SN: 22/10040/59

Biery had a full-time job, so the restoration was done mostly on weekends. With the body in such poor condition, he had to remake a lot of it. DKW’s decision to use a fiberglass body really helped the restoration. Still, it took several years to get the panels to the point where he could refinish them. The car’s original color was determined thanks to finding the original color on some of the interior panels. Knowing that, the interior color could also be determined. The car now wears its correct and original color. Thinking about the effort, Biery smiled and said, “It was fun; a labor of love.” It sure helps to have a friend like Biery when you have a very unusual car to restore.

Driving Impressions

We meet at Fort Clinch State Park on Amelia Island, Florida. Lane was going to show the car at the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, so it provided a great opportunity to gather the information and photographs for this profile. After moving to a shady spot under a great oak tree, we, my friend Dave Allin, who drove the camera car, and I, spent time learning about the Monza. As a three-cylinder, two-stroke, it’s quite a bit different than anything I had driven before.

For a car this low and small, it is easy to enter and comfortable once in. The steering wheel is a little close to the seat, but it is still surprisingly easy to enter. There is a back seat that might be used for children, and there is adequate luggage space. The dash has minimal gauges, but the necessary ones are there. The standard four-speed shift pattern is on the end of the column shifter, so it is best to learn it before trying to pull away.

After driving this pretty car, I came to the conclusion that Auto Union blew it when they engineered the market failure of the Monza. My opinion is that it could have been a very successful mass-market model. It was attractive, had good performance and was comfortable to drive. Instead, Auto Union put the emphasis on its pseudo Thunderbird, the 1000SP. But who said group think in the executive suites of an auto company is a good thing?

Thanks once again to Jeff Lane for allowing me to experience another of the unusual automobiles in his museum. I’ve got to get back there to see what he has added since my last visit.

Specifications

Construction: Fiberglass body on steel chassis Engine: 3-cylinder, 2-stroke Displacement: 896 cc Bore: 71 millimeters/2.8 inches Stroke: 76 millimeters/2.99 inches Comp. Ratio: 6.5:1 Horsepower: 38 hp @ 4200 rpm Torque: 52 lb-ft @ 3000 rpm Transmission: Four-speed, cable-operated, column shifter Induction: Solex 40JCB carburetor Cooling: Thermosiphon Length: 4090 millimeters/161 inches Width: 1610 millimeters/63.4 inches Height: 1350 millimeters/53.1 inches Wheelbase: 2350 millimeters/92.5 inches Front Track: 1190 millimeters/46.9 inches Rear Track: 1250 millimeters/49.2 Inches Curb Weight: 780 kilograms/1720 pounds Brakes: Four-wheel drum Wheels: Steel disc 5.6×15