When someone says “Sunbeam,” most car people immediately think of the “Tiger.” Sunbeam was much more than just that one model, and the subject of this profile is much rarer than the V8-stuffed Tiger.

Origins of Sunbeam

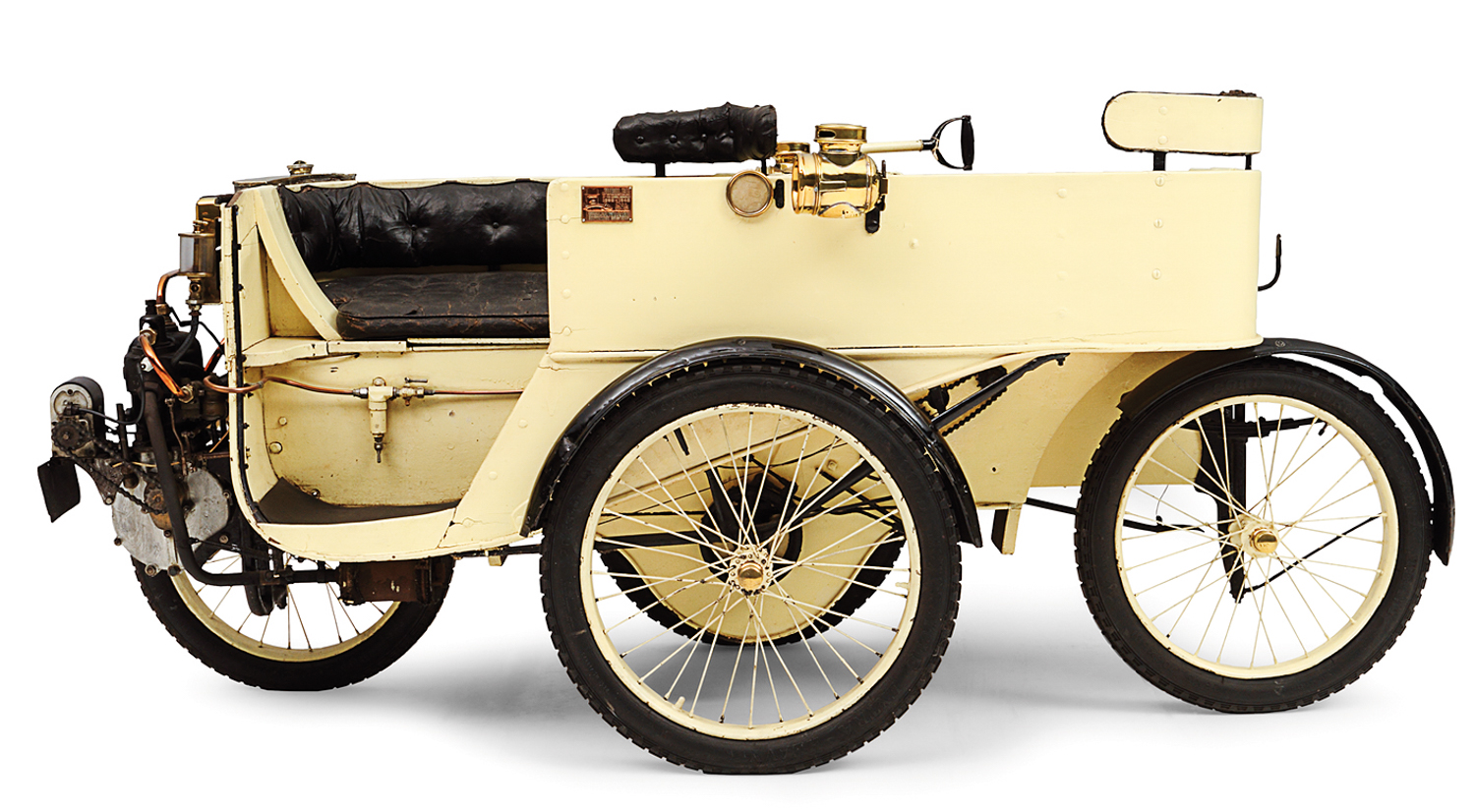

John Marston created the Sunbeamland Cycle Company in England, in 1887. In 1899, Marston’s assistant, Thomas Cureton, designed and built a single-cylinder car. Marston was impressed enough to fund the second car, this one with a horizontal engine. As his interest grew in automobiles, he became impressed with a design by Mr. Mabberly-Smith. Its four wheels were arranged in a diamond shape. There was a single, chain-driven wheel in the front, then two wheels in a more “normal” arrangement, and a single wheel in the back. The front and rear wheels were offset from each other – not in line – and the driver steered both with a tiller. It was powered by a 2¾ Hp DeDion-Bouton engine and had three seats facing sideways. Named the Sunbeam-Mabley, it sold well – 150 in its three years of production.

The Sunbeam 12 Hp replaced the Mabley. It was a more conventional design done by Thomas C. Pullinger and was based on a Berliet. The year 1905 saw a name change from John Marston Ltd. to Sunbeam Motor Car Co. Ltd. and a move to producing cars with larger engines. Designed by Angus Shaw, the new cars had a 3400-cc engine and was designated the 16/20 Hp model. The arrival of French engineer Louis Hervé Coatalen saw some significant changes to the company’s products and, eventually, to a new focus on competition. Coatalen became Sunbeam’s designer, supervisor of manufacturing, and test driver for all the cars the company produced. His first effort was to redesign the 16/20 Hp and enlarge the engine to 3825-cc. He saw the need for a model with less power and designed a 12/16 Hp, which would provide the majority of Sunbeam sales in 1910. In 1912, Sunbeams came with a Monobloc engine with an L-head replacing the previous T-head. Coatalen also designed two six-cylinder cars for the company. Sunbeam’s lineup at the beginning of WWI included the 12/16 in standard and sporting models, the 16/20, and a 25/30 six-cylinder. It was through Coatalen’s efforts that company profits increased by a factor of 100 between 1909 and 1913.

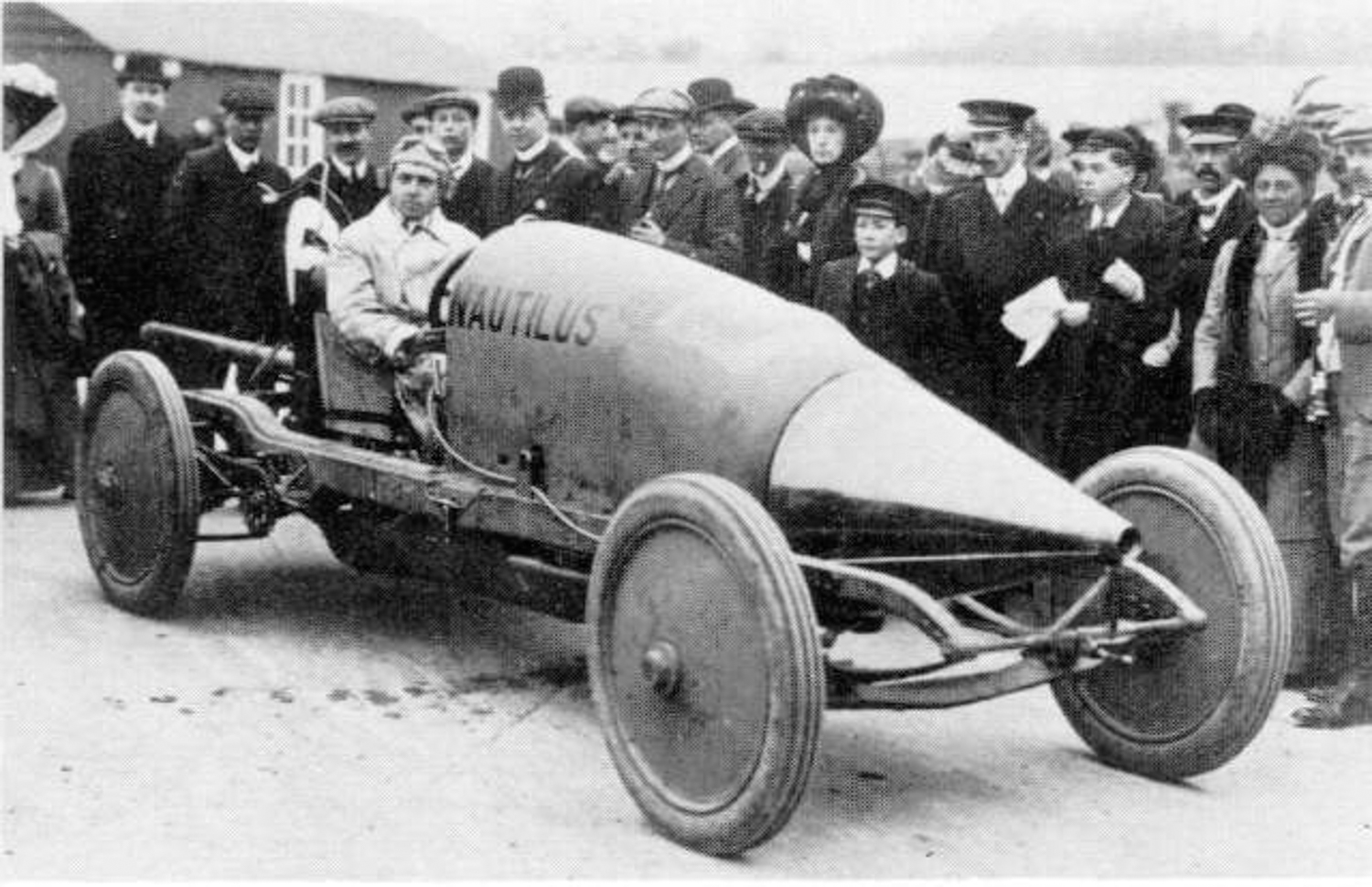

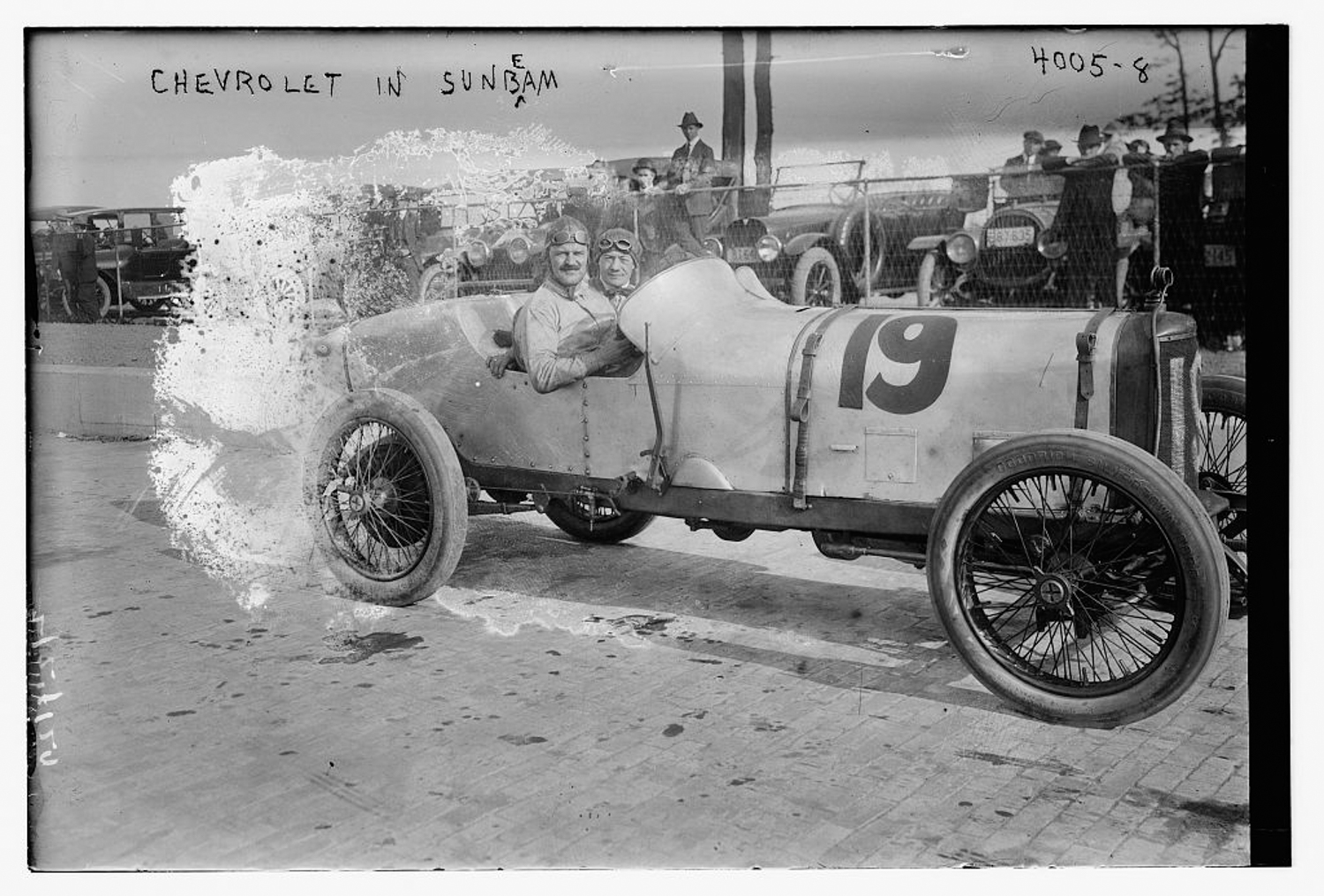

Coatalen saw another way to promote the products he was designing – competition. He raced in sprints and hillclimbs, but his most significant effort was designing and building specials for racing at Brooklands and would eventually lead to the company’s pursuit of speed records. The first special, “Nautilus” was not successful. “Toodles II” came along in 1911 and won three races with Coatalen driving. Toodles II had a single overhead cam engine and shaft drive and turned a mile at 86 mph. “Toodles IV” had a side-valve engine producing 30 hp. Dario Resta used it to set a world hour record at 92.45 mph. Coatalen developed a three-liter car for the Coupe de l’Auto in 1911. It was a two-seater with a streamlined body and a Monobloc engine with four-speed transmission with overdrive. It retired from the race, but Coatalen came away with ideas for the car in 1912. The redesigned car had a narrower body, pointed tail, and an engine now producing 74 bhp. The Coupe de l’Auto was run together with the French Grand Prix, and the Sunbeams finished first through third in the Coupe and third through fifth in the Grand Prix, beating cars with much great displacement engines. A spin-off from racing was a new 12/16 with a 3016-cc, race-derived engine. It was available in touring and sporting versions.

In the few years before WWI Sunbeam racers had some successes, but 1912 was the apogee. That may have been partly because of Coatalen’s focus on aero engines starting in 1913. While some of these engines were installed in automobiles for land speed record attempts, the company primarily built aero engines in support of the war effort. Production of the 12/16 continued through the war, although the car was constructed by Rover.

With the war over, the company returned to building automobiles. In an attempt to expand, in August 1920, the Sunbeam Motor Car Company joined with A. Darracq and Company, Ltd, which had acquired the Clement-Talbot Company. The new group was called S.T.D Motors, Ltd., for Sunbeam, Talbot, Darracq. Darracq, though, continued to produce cars in France, which resulted in money being siphoned off from the English side to support French production. Worse, Coatalen eventually returned to France, in 1926, to work. The company continued to build versions of its pre-war cars with improvements such as optional four-wheel brakes, more power, and an engine with four valves per cylinder.

The first truly new Sunbeam had appeared in 1922. It had an overhead valve four-cylinder engine of 1954-cc displacement. This model was improved over the next few years and was joined by two six-cylinder models. In 1925, four-wheel brakes were made standard. That year, Sunbeam produced its “3-Liter” sporting model. It was a significant automobile. Its engine displaced 2916-cc, was a dual overhead cam engine with hemispherical combustion chambers, and produced 90 bhp at 3800 rpm. While it was expensive compared to other Sunbeams, a second place finish at Le Mans in June 1925 resulted in a boost in sales.

It wasn’t only at Le Mans that Sunbeam saw success in competition. The company was quite active in motorsports during the first half of the 1920s in both track racing and land speed record attempts. In 1922, the four-cylinder, two-liter Sunbeam engine was redesigned for competition the following year. With a DOHC six-cylinder engine in the 1922 chassis, Sir Henry Seagrave won the French Grand Prix, the first win by a British car in a European Grand Prix. Sunbeams also finished second and fourth in France. Lee Guinness, who had finished fourth in France, won the Spanish Grand Prix. The decent finish at Le Mans, in 1925, was one of the last good finishes by the British team as racing was transferred to Talbot in France after that.

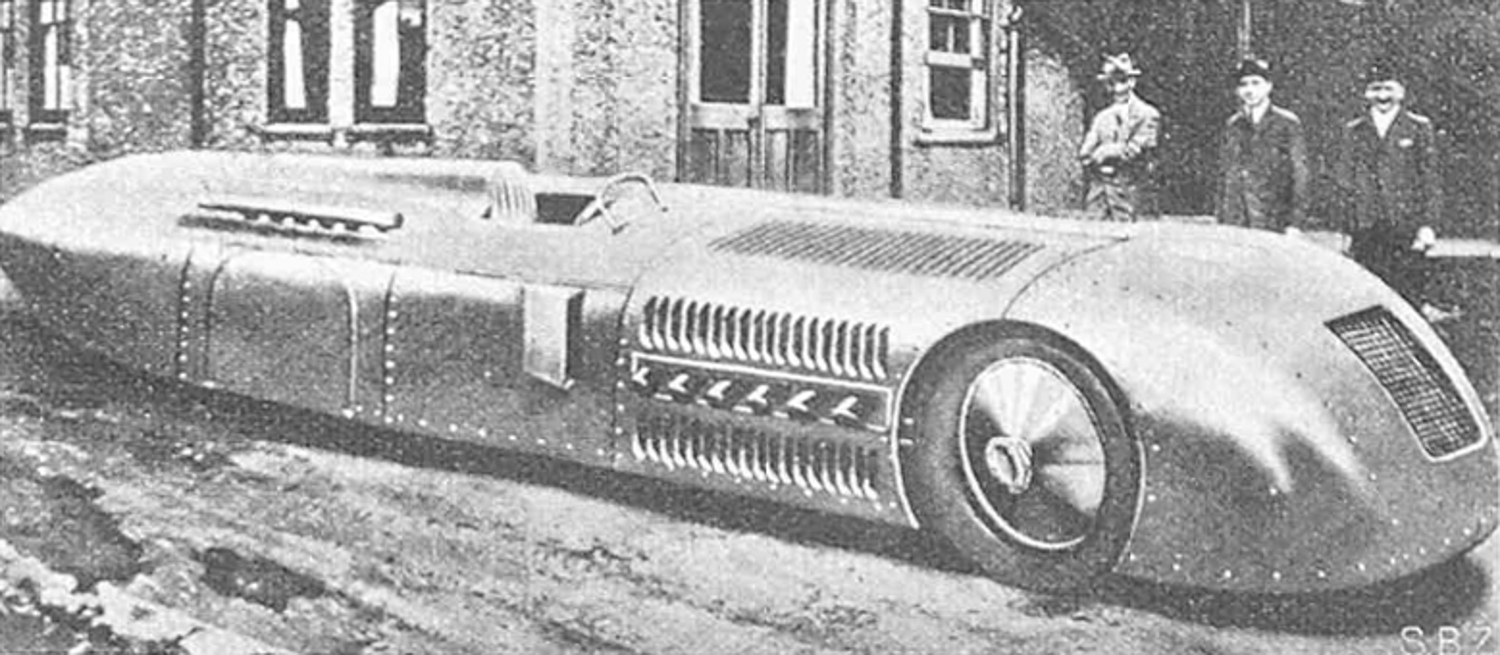

Even though it was no longer track racing, Sunbeam had made a name in setting land speed records, and that continued. Several drivers used the same car to set, then raise records between 1920 and 1925. First it was René Thomas with a Fastest Time of the Day at Gaillon. In 1922, Lee Guinness used the car to set a record of 133.7 mph at Brooklands. Then it was Malcolm Campbell’s turn. During 1923, he raised the record twice, he set a new record of 146.2 mph in 1924, then raised it again to 150.88 mph in 1925. By 1930, Sunbeam had set more than 30 land speed records. Seagrave used the 296 hp supercharged 3976-cc V12 “Sunbeam Tiger” to raise the record to 184 mph in a car that looked like a normal racecar. The 1927 “1000 HP Sunbeam” was run at Daytona Beach and raised the record to 203.79 mph. The car had two Sunbeam aero engines displacing about 45-liters. One engine was in the front and one in the back of the car, which was chain driven. That record was broken three times over the next two years, and Sunbeam made an attempt at it with their “Silver Bullet,” a 48-liter V12 machine, but it was unsuccessful. There was a period when Sunbeam held every record from the 50 to 1000 mile distance.

Sunbeam’s production vehicles suffered after Coatalen’s departure. He was replaced by Hugh Rose, who was more interested in commercial vehicles and left in 1932. After Rose’s departure, it was two years before H.C.M. Stevens was named Chief Engineer. Stevens was an innovative designer but was constrained by a lack of funds for the development of new models, and especially larger cars. He did design and produce the Sunbeam “Dawn,” which included a number of new features. It had a four-cylinder, 1627-cc overhead valve engine with an aluminum block that produced 49 hp. It used a preselector gearbox and had an independent front suspension. Unfortunately, it was more expensive than the competition, and few were sold. By the spring of 1935, S.T.D. was in receivership, and the company was bought by the Rootes Group and renamed Sunbeam-Talbot Ltd. As the world moved toward WWII, the cars were renamed Talbots, but they were models based on the Hillman Minx and Humber Super Snipe. The Talbot models were revived after the war and were now built in the Rootes plants where the Hillman and Humber models were produced.

A Sunbeam After the War

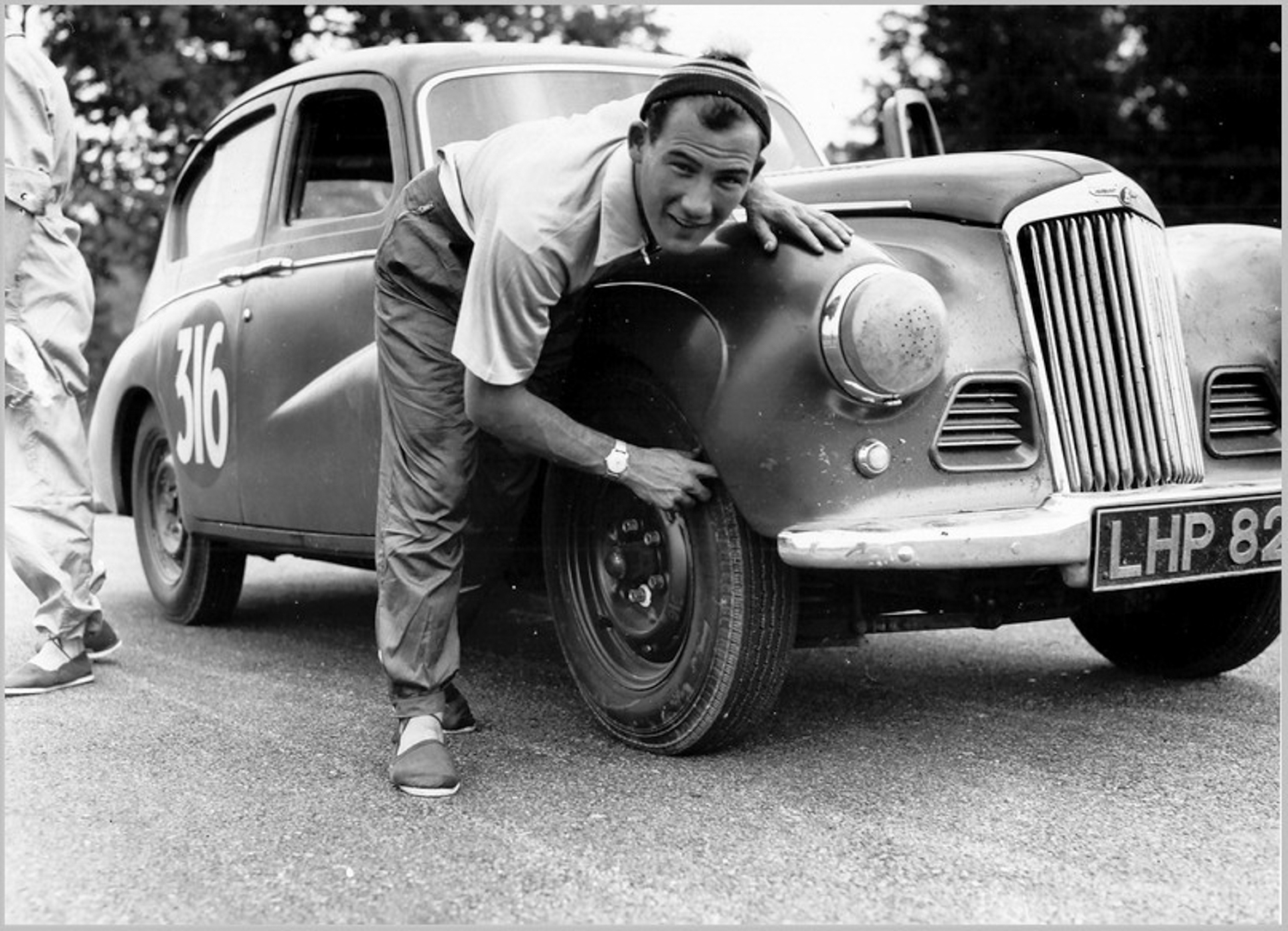

Sunbeam-Talbot, as a marque, was back with the Alpine in 1953. It was based on a touring car design, so it was heavier than sports cars like the Healey 100 and TR2, but it proved to be a very sporty two-seater. It had a high compression engine producing 80 hp and was graced with higher geared steering. The Alpine turned out to be a very successful rally car. It was driven to wins in Europe, at the Coupes des Alpes and Monte Carlo Rally, as well as at events in the U.S. and Australia. One of the drivers was Stirling Moss, who became the second driver ever to win the Alpine Gold Cup for winning three events in a row without a penalty point.

It is said that competition improves the breed, and it was certainly true for the Alpine. Rallying resulted in improvements to the car’s brakes, cooling system, and chassis. The MK III Alpine, now badged simply as a Sunbeam, certainly benefitted from the improvements, including a new cylinder head, increased power, competition brake linings, and an optional overdrive. A total of 2250 Alpines were built through February 1957. It was eventually replaced by the Rapier, essentially a Hillman Minx with a much nicer body, apparently penned by Raymond Loewy. The Rapier was also a successful rally car, winning the 1958 RAC Rally overall. It had racing successes as well, finishing second and third in the Mille Miglia in 1956, and taking Peter Harper to the BRSCC Saloon Car Championship in 1961.

A New Alpine

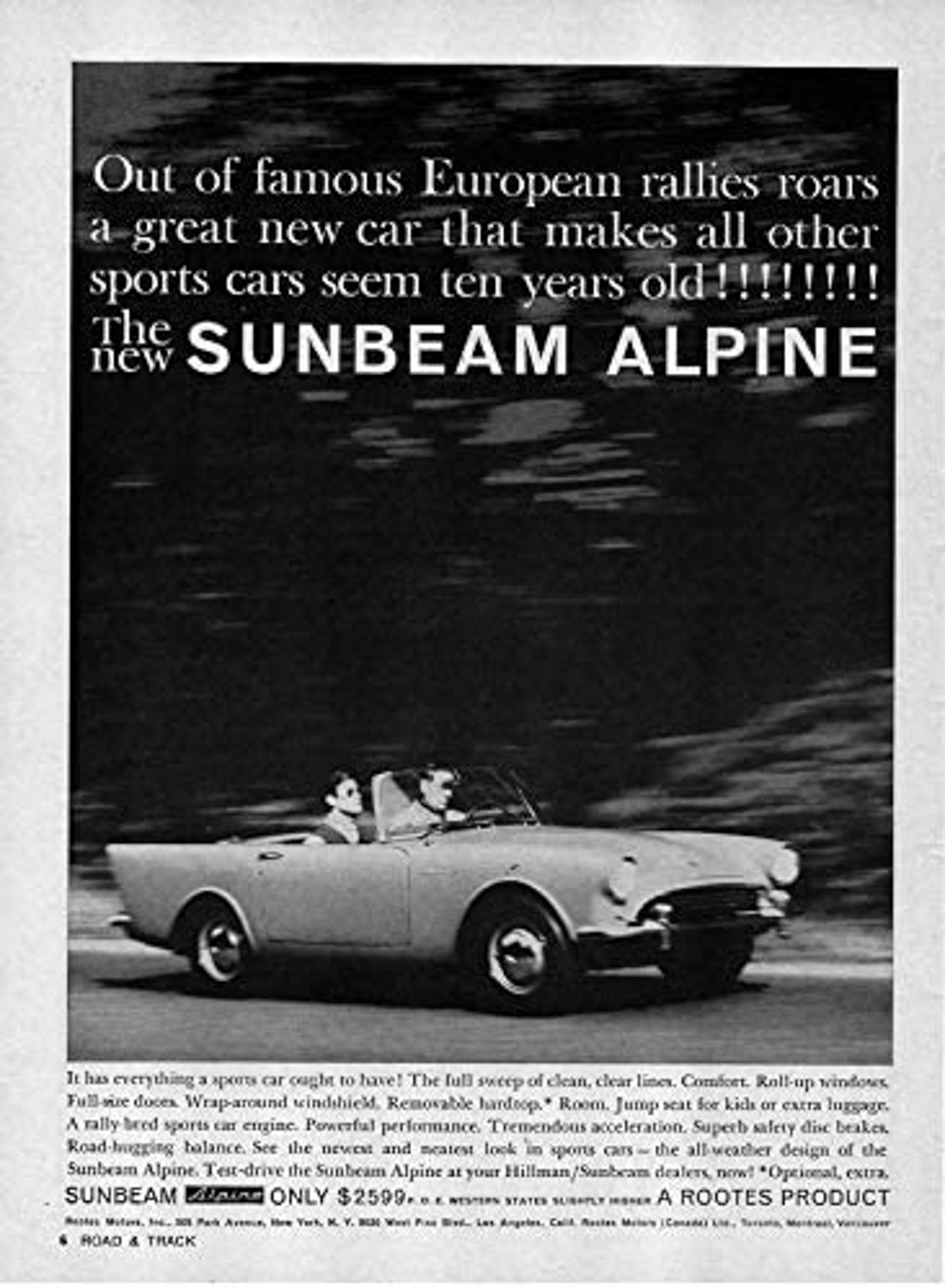

The Alpine known to most of us, and the model which is the subject of this profile, began in production in 1959. The new Alpine Series I used the floorpan of a Hillman Husky and its 1494-cc engine with dual downdraft carburetors. It was a parts bin car, as it used many bits from other Rootes Group cars. The driveline was mainly from the Rapier. Girling disc brakes replaced the Rapier’s drums on the front, and the car was given an independent suspension with coil springs at the front and a live axle with semi-elliptic springs at the back. The body was designed by Kenneth Howes and came with the first wind-up, side windows in a British sports car. One part of his design was certainly a popular element of the time – rear fender fins.

When it came out in late 1960, the MKII Alpine received a 1592-cc engine making 80 bhp and a revised rear suspension. The MKIII had the shortest production life, from March 1962 – January 1963. It came in two models – a GT with a removable hardtop and an ST with a soft top. The GT had no soft top. This was the last of the “high fin” Alpines; the MKIV (1964-’65) had the fins mostly removed from the rear bodywork. An automatic transmission was offered as an option, but it was not a popular option, especially after a new manual with a synchro first gear was introduced. Series V Alpines (1965-68) were the last of the line. There was no longer an automatic transmission option, and the engine was now 1725-cc and producing 92 bhp. The MKV is probably the most desired of the Alpines. There was one other Alpine, a four-seater called the “Venezia” designed by Carrozzeria Touring. Only 145 of the Venezia were built from 1963 to 1965.

Alpines on Track

The Alpine proved to be a popular race/rally car. There were wins at the RAC Rally, Tour de France, and Scottish Rally. An Alpine also won the Index of Thermal Efficiency at Le Mans in 1961.

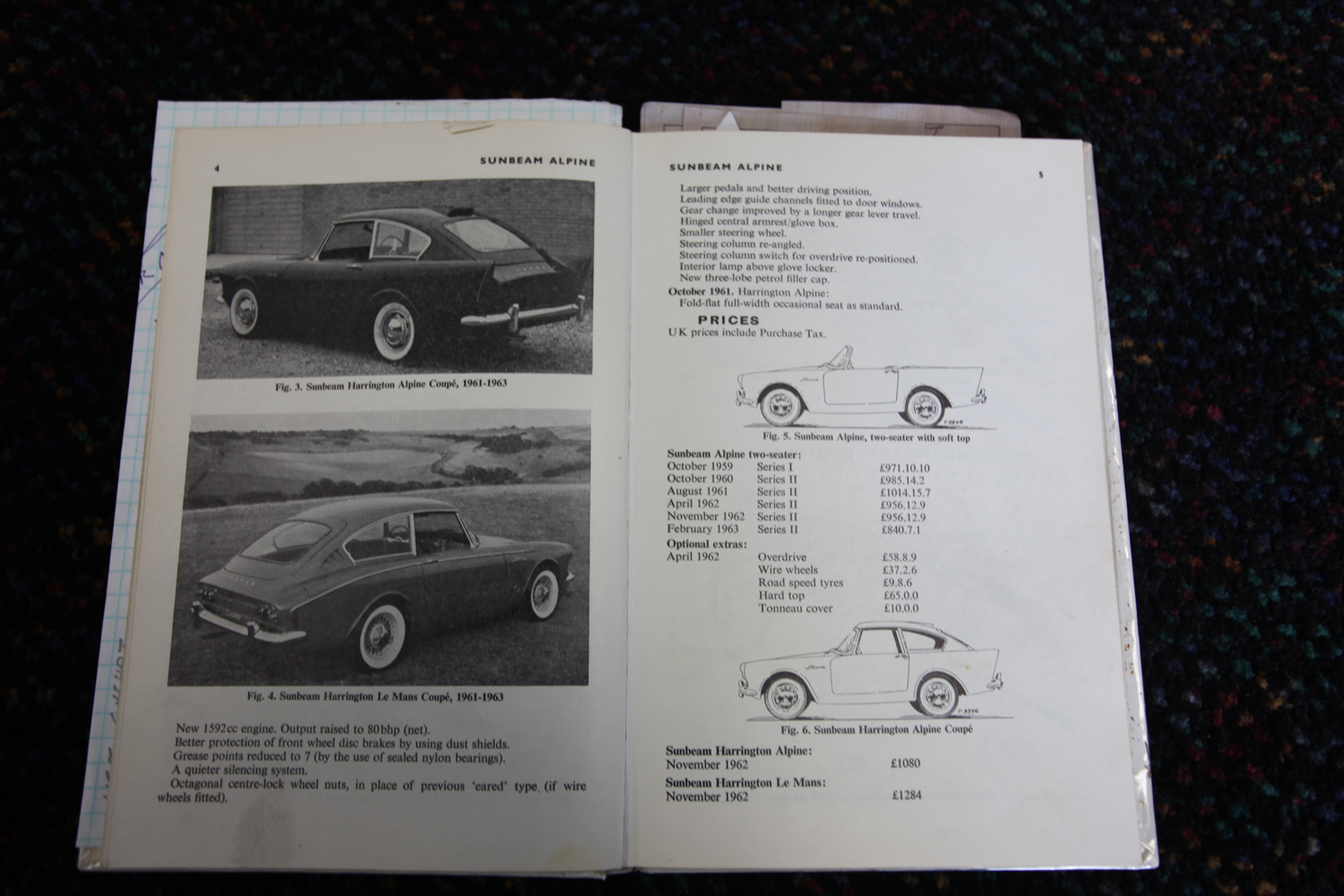

There are those who believe this trophy carries as much honor as an overall win at Le Mans. It was significant enough that Rootes had a special edition of the Alpine modified by Thomas Harrington, Ltd. The first Harrington Alpine was the Series A Harrington and was a fastback. It was designed prior to the Le Mans result. A run of 150 or so were built in 1961. In honor of winning the Index of Thermal Efficiency, a total of about 250 Series B Harrington LM fastbacks were built in 1962-’63. Our profile car is a Series B.

Thomas Harrington, Ltd. and the Harrington Alpines

Harrington was an early producer of bodies for automobiles and motor coaches. Most of the autos they bodied were from British, German, French, and Italian automakers. Among the British cars they bodied were ones from Rolls-Royce, Talbot, Austin, and Sunbeam. They were responsible for the Harrington Alpines, as well as versions of the Dove GT (a Triumph TR4 variant) and Minis. The “Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile – Coachbuilding” notes that the company announced “a major extension of its works in 1966” then closed the company later that same year. The loss of Harrington is unfortunate because the quality of their work was exceptional. Manufacturers, though, were making less use of coachbuilders by the middle 1960s.

The Harrington Alpine was first shown in March 1961. It was followed by the Harrington Le Mans, Harrington Model C, and Harrington Model D. There was even a Harrington Tiger. There were fewer than 400 Harrington-modified Alpines based on Alpine MK III through MK IV chassis. It is a challenge to determine when each of the models began and ended production, since a buyer could often choose an older model while a new model was being produced. If production of the Harrington Le Mans was underway, and you preferred the older body style, you could order a Harrington Alpine. All models were open cars converted to a fastback GT. The biggest visual difference between the Harrington Le Mans and other Alpine versions was that the fins that were so prominent on the earlier Alpines were removed on the Le Mans. The Harrington Alpine also had a fixed rear window and a small trunk (boot) lid. All the other models accessed the rear of the car through a rear hatch that included the rear window.

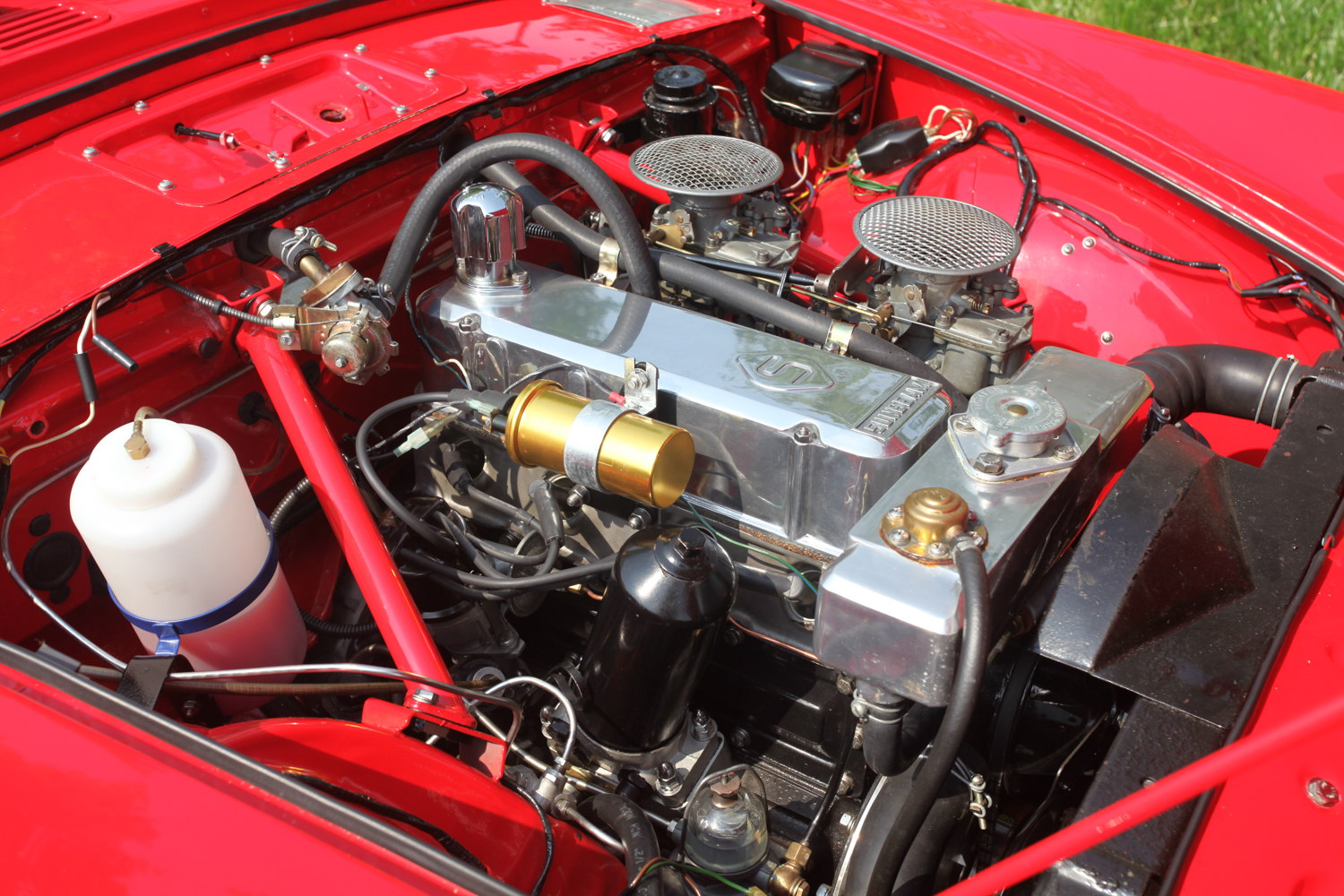

Harrington used a fiberglass fastback roof to change the car from a convertible to a GT. When someone ordered a Sunbeam Harrington at a dealership, the order was teletyped to Sunbeam, where they would pick the next one of the color ordered and tell the floor it was going to Harrington. The car would be completed at Sunbeam and would be sent to Harrington, where the engine and transmission would be pulled and sent to George Harwell, a motor specialist. The head would be ported and polished, the flywheel and clutch balanced, a hotter camshaft installed, jets changed in the carburetors, and the timing tweaked for a Stage 1 tune. Stage 2 included Weber carbs and special manifold and headers, which provided 105 bhp. Steering was not changed; it was standard Sunbeam. It was a car that would be ordered with no options – options were placed on the car at the dealership. Rootes, for example, made their own driving and fog lights as dealer installed options. The lenses had Rootes on them and are very rare. An owner could dress up interior with optional mats, and could select red, white, or black piping on the interior bits. A center console, ashtray, and cigarette lighter were standard.

Harrington received the car as a roadster and then had to transform it into a GT. Except for the Le Mans, the fins were left on the finished Harrington Alpines. The Sunbeam Harrington Le Mans required even more metal work than the other Harrington Alpines, since the rear quarter, trunk, and fins all had to be removed. When the metal was cut, the remaining metal was left longer than the final design so it could be bent 90° to provide a surface to which the fiberglass fastback could be attached. The metal was drilled every 6-8” and the fastback was held in place with #10 machine screws. The area between the fiberglass and metal was filled with a material to seal the connection. Only the area where the work was done was painted. Imperfections were hidden by a stainless-steel strip.

The new bodywork was minimally reinforced, but it was enough to provide a stable, solid car, in part thanks to the car’s monocoque design. While the new bodywork was made a permanent part of the car at the rear, the front of the fastback was secured in a way designed to do the job while saving money. At the front, the standard convertible top latches were used to secure the fastback. The latches were drilled and tapped, then countersunk machine screws were used to provide a safe, permanent attachment for the roof. This parts bin solution saved considerable time in construction and was very effective.

Sunbeam Harrington LM VIN B9116050

Our profile car was built in 1962 but is titled as a 1963. Its story includes time spent in Canada and the U.S., and a lot of time and effort to restore it. Thankfully, Reg Hahn is someone who recognizes things that deserve preservation, and was willing to do what was needed to insure that this rare automobile could be enjoyed for many years to come. His interest in Sunbeam Harringtons goes back to 1969 when he was in college. He owned a Triumph Spitfire which developed a carburetor issue while he was driving home. He stopped at a dealership in Columbus, Ohio, to get it fixed and saw his first Harrington. He was interested, but the price was out of range for him. It seems that the price of a Sunbeam Harrington Le Mans as delivered in the U.S. was higher than a new Jaguar E-Type Coupe, so they were expensive. Hahn never lost his interest in Sunbeam Harringtons, but it would be more than 50 years before he had another chance to buy one. He was in Florida when a friend called to tell him about a Harrington that was being offered at a little country auction. It was in an estate along with several DeSotos, a Model A pickup, and containers of DeSoto parts. Hahn went online and was soon the high bidder, but his anxiety was increased as the auction was extended three times before he was declared the winner. A friend picked up the car and brought it home to Ohio for Hahn. That’s when he found many issues with the car. But he realized that a car as rare as this one needed to be preserved, and he committed to doing what was necessary to fix the issues.

Rust is a serious issue with Sunbeams. They weren’t expensive cars, so they were often expendable, which makes many parts rare. And rust was a serious problem with Hahn’s Harrington. When you buy a car sight unseen, you have to be ready for some surprises, and they were significant. The floors were rotted, rocker panels had been replaced incorrectly, and interior wheel wells were rusted, but those weren’t the worst of the surprises. Hahn put the car or a rotisserie and tried blasting the body to see what was under the paint. He quickly realized that he had to stop, since he found that much of the metal was gone on the rear fenders. The previous owner had used copper screen to form “fenders” then mudded them into something that resembled the original shape. Blasting would have resulted in large holes where bodywork should have been. Hahn needed help, and, luckily, he found it.

One find was a Sunbeam workshop manual on eBay that had a section on the Harrington cars appended to it. Another find was Ian Spencer, who, together with another fellow, created the Sunbeam Harrington Club in Ohio. They were great sources of information for odd details about the car, like how to remove the windshield – it tilts inward to get it out. His best find though was Randy Willett in New Hampshire. Willett is a bodywork craftsman who knows Harringtons. He does not advertise, so it was by word of mouth that Hahn found him. To get the car to Willett, Hahn put the car mounted on the rotisserie on a rollback truck, then into a rented Penske truck. Hahn made wooden cradles for the rotisserie casters and tied it all down for the trip to New Hampshire. Once at Willett’s shop, the rotisserie-mounted car was unloaded by a forklift. Two years later, Willett had replaced all the rotted bodywork using the original designs. Now it was time for Hahn to put it all back together.

It took a total of four and a half years to get the car to the condition it is in today. There were many challenges. For example, front end parts are not available, so he had to use Series IV and V front sub-frame assembly components – a normal approach for restoring early cars. Parts sources can also be a problem. Many parts from China and India are not good quality. Hahn believes all the time and effort were worthwhile, since he now has an excellent example of a very rare British sports car. And there is a possibility that his car is the cover car for an issue of Road & Track from 1966. He suspects that his is not that car, but it makes for good conversation. Turns out that there are quite a few Sunbeam Harringtons in Ohio, possibly because George Byers was a successful Sunbeam dealer in Columbus, where Hahn saw his first one.

Driving Impressions

As I age, I find that there are an increasing number of cars that I cannot enter on the driver’s side. A replacement hip on one side and a bad one on the other limit my ability to get through a narrow door, under the steering wheel, and into the driver’s seat. So, I get special rides with the owners of some of the cars I profile. Being a passenger is not necessarily a bad thing, since the owner will often drive his or her car with considerably more “enthusiasm” than I would – I am not going to hurt one of these wonderful, old, rare automobiles. Riding as a passenger also gave me more time to look over the interior appointments of the car. From the passenger seat, the Sunbeam looks like a number of other British cars I’ve owned or known. The first thing you notice is the wonderful wood dashboard. It’s an upgrade, one that’s done by many Harrington owners, since Hahn describes the original wood veneer dash as “funky.”

There’s a full complement of electric gauges and a direct measurement oil pressure gauge. All of the gauges were rebuilt by Peter Nisonger, a Smith’s gauge specialist. The Smith’s clock even keeps time! As Hahn says, “most of the time Smith’s clocks are right twice a day,” so his is a nice surprise. The clock is an option; a blacking plate replaces it on cars not so optioned. The steering wheel is large with three spokes and a nice wood rim – pretty too. There are three stalks on the steering column. The one of the right controls the turn signals. On the left are the horn (inner stalk) and overdrive control (outer stalk). The car has a Norman Deauville overdrive system that works on third and fourth gears, so, if you like to play a bit with the shifter and the overdrive stalk, you have a six-speed transmission. When overdrive is engaged, a green light shows on the dash. There is a lockable center console that is standard equipment. The car came with lap belts, but they were equipped for three-point belts, which Hahn has added. Another thing Hahn added is a transmission from a Series IV Alpine that is synchronized in all gears. The stock transmission did not have a synchro first gear, which resulted in many of them dying an early death when owners tried to downshift straight into first.

Hahn’s Sunbeam Harrington Le Mans is a Stage 2 car, meaning that it produces 105 hp. Weighing 2100 pounds, the Harrington is not a rocket ship when accelerating, but it is very comparable to other British sports cars of the same era. It accelerates from a stop nicely. You can induce wheel spin, but that’s not the quickest way to get away at a stop light. As a passenger, the car seemed quite nimble and responsive. Hahn called it “light – a point and shoot car. You find your apex, and you go for it.” Although we were mostly driving on suburban streets, there were plenty apexes to go for. The car exhibited very little lean, thanks to a large stabilizer bar in the front added by Harrington. From the factory, the car came with lever shocks, but there is a retro-fit for Konis. Hahn’s car now has adjustable shocks on the rear and non-adjustable ones on the front. While I’ve never owned an Alpine, I’ve had friends with them. I like the looks of the roadsters, but the Harrington Le Mans is just an order of magnitude prettier. It’s a nice car, and probably the ultimate Alpine of the modern era to own – even more so than the Tiger.

Specifications

| Body Style | Roadster conversion to GT |

| Length | 3942 mm/155.2 inches |

| Width | 1537 mm/60.5 inches |

| Wheelbase | 2184 mm/86.0 inches |

| Weight | 2100 pounds/952.544 kg |

| Engine | Front four cylinder OHV |

| Displacement | 1725 cc/105.3 cid |

| Bore/Stroke | 82 mm (3.2 inches)/83 mm (3.3 inches) |

| Horsepower | 105 bhp at 5500 rpm |

| Torque | 103 ft-lbs at 3700 rpm |

| Compression ratio | 9.2:1 |

| Carburetion | Dual Strombergs |

| Transmission | Four speed manual with Norman Deauville Overdrive |

| Suspension | Independent front/ live axle rear |