William C. Durant

The Chevrolet Motor Company exists because William Crapo Durant was fired in 1910 from the company he created two years earlier, General Motors. Durant wanted to regain control of GM, but he needed capital. To get capital, he needed a car to sell, so he created the LITTLE Motor Car Company in order to produce an inexpensive automobile. He then prevailed on Louis Chevrolet to join him in the creation of the Chevrolet Motor Car Company. Chevrolet was a well-known racer, having raced Buicks successfully. What he wasn’t was a designer, so Chevrolet asked his friend Étienne Planche to join him and Durant. Planche had designed the first Mercer, so he had credentials as an automobile designer. Their company was incorporated on November 3, 1911, and production began in 1912.

Louis Chevrolet

Before discussing the cars that carried the Chevrolet name, a little of the history of the man with the name is in order. Louis Chevrolet was born in Switzerland in 1878. His family was of French origin, and they moved back to France when Chevrolet was ten. Chevrolet was interested in both technology and competition. He was a bicycle racer and moved to automobiles as they were being developed. Before coming to the US, via Canada, in 1900, Chevrolet had worked for Mors, Darracq, Hotchkiss, and De Dion Bouton. After a short time working as a chauffeur, he joined De Dion Bouton in the US. He raced and won with Fiats, gaining a reputation for his abilities. Chevrolet joined Buick in 1907 and became well known for racing those cars. It was where he met Durant.

Durant hired Chevrolet for his technical expertise to help develop Durant’s new car. The car would be designed by Planche and tested by Chevrolet. But there was quite a bit of friction between Chevrolet and Durant. Chevrolet was not pleased that his name would be on an inexpensive car, and Durant did not think that Chevrolet provided an image of a successful automobile executive – he was a constant cigarette smoker at a time when executives smoked cigars.

Chevrolet left the company that bore his name in 1913 and founded the Frontenac Motor Corporation the following year. Frontenac built four- and eight-cylinder race cars that were very successful on the board tracks. Louis Chevrolet continued to race, including at Indianapolis, but it was his brother, Gaston, who won the 500 in 1920.

Frontenac developed a cylinder head for Model T Fords, which became known as Fronty-Fords, and built them from 1922-34. Alfred Moss, Stirling’s father, raced a Fronty-Ford at Indy in 1924. Chevrolet also served as the Chief Engineer for the American Motors Corporation in the 1920s. Toward the end of his life, he did design consulting until shortly before his death in 1941.

Chevrolet Motor Company

The first Chevrolet automobile was called the Classic Six and was a five-seater tourer. Its 4900-cc T-head engine would be Chevrolet’s largest until 1958. It cost $2150, which was more than a Cadillac 30. Still, Chevrolet sold more than 3000 cars in just over two months and sold 5987 in 1913. Durant realized that he had to have a much cheaper model if he was going to bank enough money to retake control of GM, so he got the Light Six, which sold for $1475. When plans for the Series H were revealed, Louis Chevrolet had enough and resigned. The two seat roadster, Royal Mail, was priced at $750 and the five seat tourer, Baby Grand, at $875. In 1914, the Classic Six sold at $2500, and its production was ended late that year.

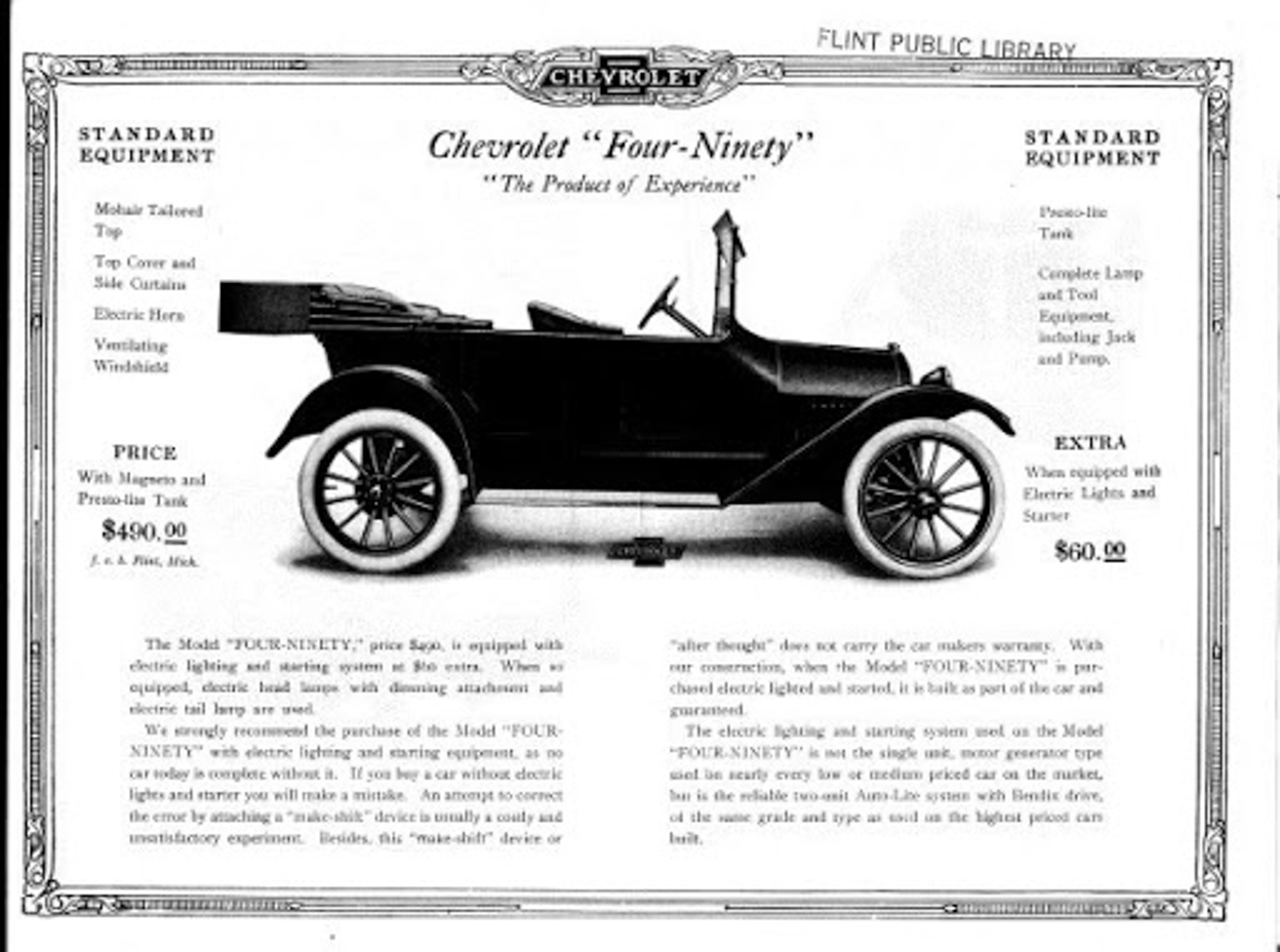

Durant took the battle directly to Ford with his 490. It was a direct competitor to the Model T and would sell for $490. Ford responded by dropping the price of the Model T to $440, winning the battle for the cheapest American car, and the Model T sold much better than the 490. There were other Chevrolet models, including a 4691 cc V8. Chevrolet was late to the V8 market – seventeen other companies already had one in their cars.

Chevrolet was enough of a success to allow Durant to regain control of GM, but he lost it again in 1920. He was forced again to resign in an agreement that included his personal debts being paid by the DuPont family and J.P. Morgan Bank. He was replaced at GM by Pierre DuPont, who considered eliminating the Chevrolet line. Alfred P. Sloan, his VP, convinced duPont to keep Chevrolet. It was a good decision. Within ten years, Chevrolet was the top selling GM line. During the 1920s, Ford and Chevrolet battled for the most sales in America until 1931. After that year, Chevrolet took a firm lead and only occasionally lost it to Ford.

Sales successes allowed Chevrolet to open new factories and introduce new models through the 1920s. One significant new model was Chevy’s first six-cylinder since 1915, nicknamed the “Stovebolt Six” because of its slotted headbolts. Automotive historian Richard M. Langworth had this to say about that engine: “It was not a high-quality power unit. Every part of it had been designed to be just good enough and no more.” “Just good enough” was apparently plenty good enough. The 3180 cc, 46 bhp engine, with improvements and modifications, continued to be one of the main engines in the Chevrolet line for thirty years. It powered 18.5 million cars and 5 million light trucks between 1929 and 1954.

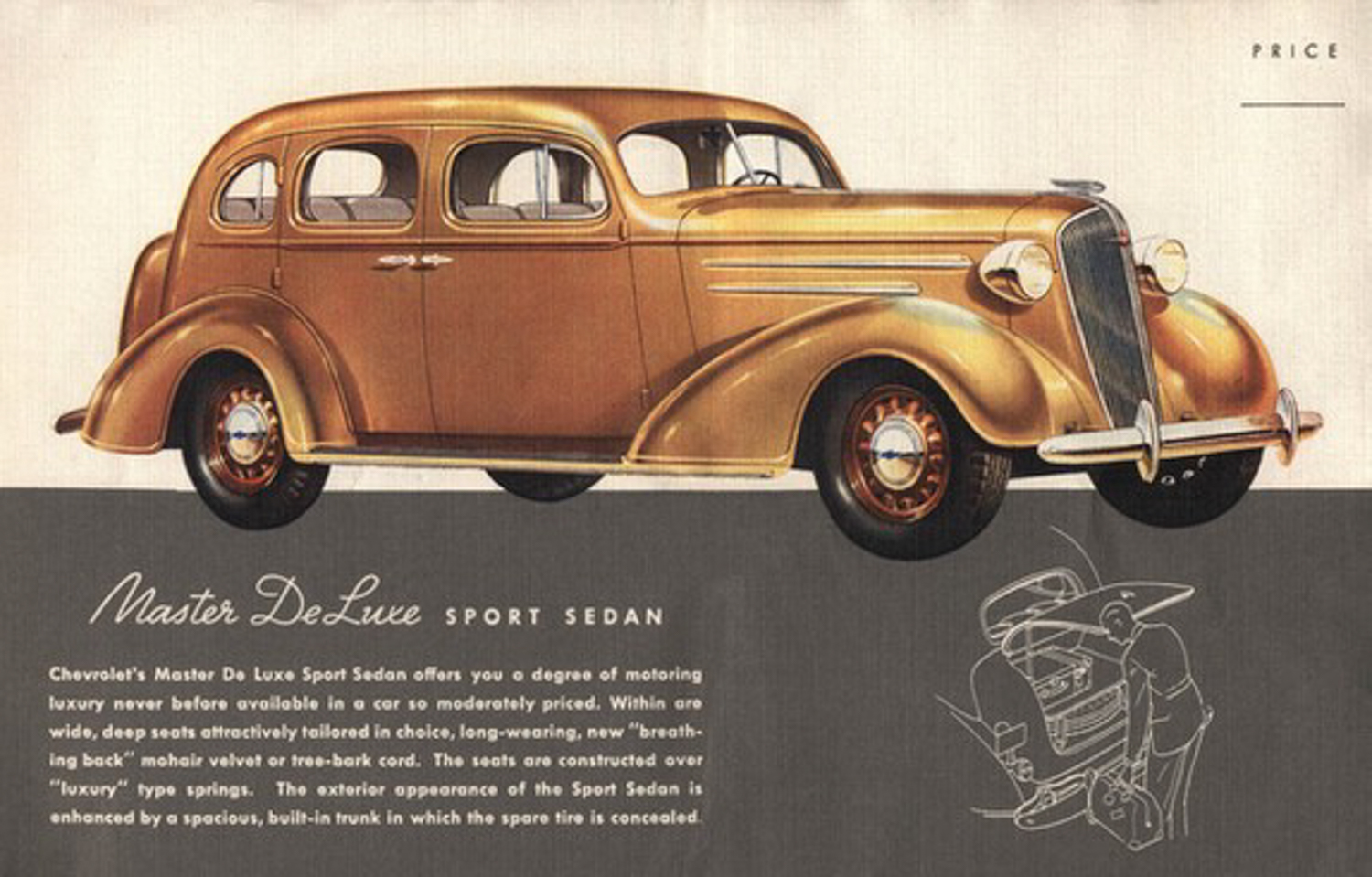

In the early 1930s, Chevrolet had a new name for its series each year – Universal, Independence, Confederate, then Eagle (a deluxe model) and Mercury (the standard model). There were some interesting developments during this time. The Confederate, for example, added a synchromesh transmission and free-wheeling. The name changes changed again in 1934, beginning the Master and Standard lines for a number of years. Independent front suspension was added in 1934, something Ford did not have until fourteen years later. Most changes to the Chevy lines were in their styling, keeping the cars current and attractive. One significant styling change came in 1935 with the addition of the Fisher Body’s “Turret Top” design. There were other additions and deletions in the years leading up to World War II. Chevrolet introduced its first station wagon in 1939, finally eliminated running boards in 1941, and added a fast back and a convertible with a power top in 1942. Those would be the last of the changes in Chevrolet automobiles until October 3, 1945, when civilian production started again.

Post-war Chevrolets looked a lot like pre-war Chevrolets, as was pretty much the case with all auto makers. Styling change became a revolution starting in 1949, compared to the styling evolutions of the previous years. The most significant of the revolutions was the Corvette. Harley Earl wanted a car to compete with the Jaguar XK-120. Three prototypes were produced on a shortened frame using a 3850 cc six-cylinder engine mated to a two-speed Powerglide transmission. The prototypes were very different – there was a roadster called “Corvette,” a fast back called “Corvair,” and a station wagon called “Nomad.” “Corvair” is said to be a portmanteau of “Corvette” and “Bel Air.” The popularity of the roadster among the public resulted in its being put in limited production in 1953. Production remained low through 1955.

1955 is a milestone year for Chevrolet. Ed Cole had designed a small-block V8, and it changed the nature of many Chevrolets. It was also the year of one of the marque’s most significant styling changes. The impact of the engine on Corvette was important, and it probably saved the model. Zora Arkus Duntov was a supporter of the Corvette, and he helped make it the iconic automobile it remains to this day. Corvette left the “Blue Flame” six-cylinder and two-speed automatic behind in 1956. The new car had a much prettier body, a V8 engine with a manual transmission, and wind-up windows.

Corvair

Before getting into the history of the Corvair, it is appropriate to address the elephant in the room when discussing Chevrolet’s unique approach to small car design. Ralph Nader’s book did not kill the Corvair. The demise of the Corvair was the result of decisions made in the Chevrolet board room. Six months before Nader’s book was published, Chevrolet decided to stop all development on the Corvair except those needed to meet air quality and crash requirements. The Chevrolet line was becoming very full – Chevy II, Camaro, Chevelle, and full-size cars. There simply was no room left for the Corvair. And, the sporty car set had the Mustang.

As for its poor handling, Nader has been completely rebuffed. Well before Nader’s book, there was a lawsuit in 1962 claiming that the car was unsafe. GM called a couple expert witnesses to attest to the car’s safety – Stirling Moss and Juan Manuel Fangio. Dan Gurney, while racing the Porsche flat-eight open-wheel racers, drove a supercharged Corvair Monza Spyder around Europe. The U.S. Department of Transportation tested an early Corvair against other cars in its class, in 1971, and determined that the car was not dangerous. More recently, Larry Webster wrote an article for Hagerty Insurance’s magazine about the Corvair. He tried his best to make the car do what Nader claimed without success.

So, what’s a Corvair like? Karl Ludvigsen answered that question in an article for Automobile Quarterly (Volume VIII, No. 4, Summer 1970), not long after Chevrolet had stopped production. In his article titled “Remember the Corvair? Here’s a Look at What We Lost:” “The Corvair was nothing if not a lovable car. Every time I drive one I am charmed by its lightness, its willingness, its completely agreeable personality. And while most cars today have a manufactured personality, the Corvair’s is built-in. It is a car that, unlike most, is far more radical in engineering than its appearance admits. What a difference from the rest of today’s cars, which do their best to glamorize a dull mechanism. Far from dull, the Corvair was that rare achievement, a completely unique automobile. There had never been one quite like it before. And there probably never will be again.”

The next question is how did we get the Corvair? The simple answer is that it was needed. Cars such as the Volkswagen and Renault had shown that there was a market for compact, economical cars even in the early 1950s. The Recession of 1957 added additional emphasis on “economical.” Chevrolet had little choice but to join Nash (American), Ford (Falcon), and Chrysler (Valiant), but with what? Shortly after WWII, Chevrolet had designed a small car called The Cadet, but a strong economy caused the design to be shelved. The Corvair was Ed Cole’s response to the market, and it was a complete divergence from all that was normal in American auto manufacturing – it broke all the rules.

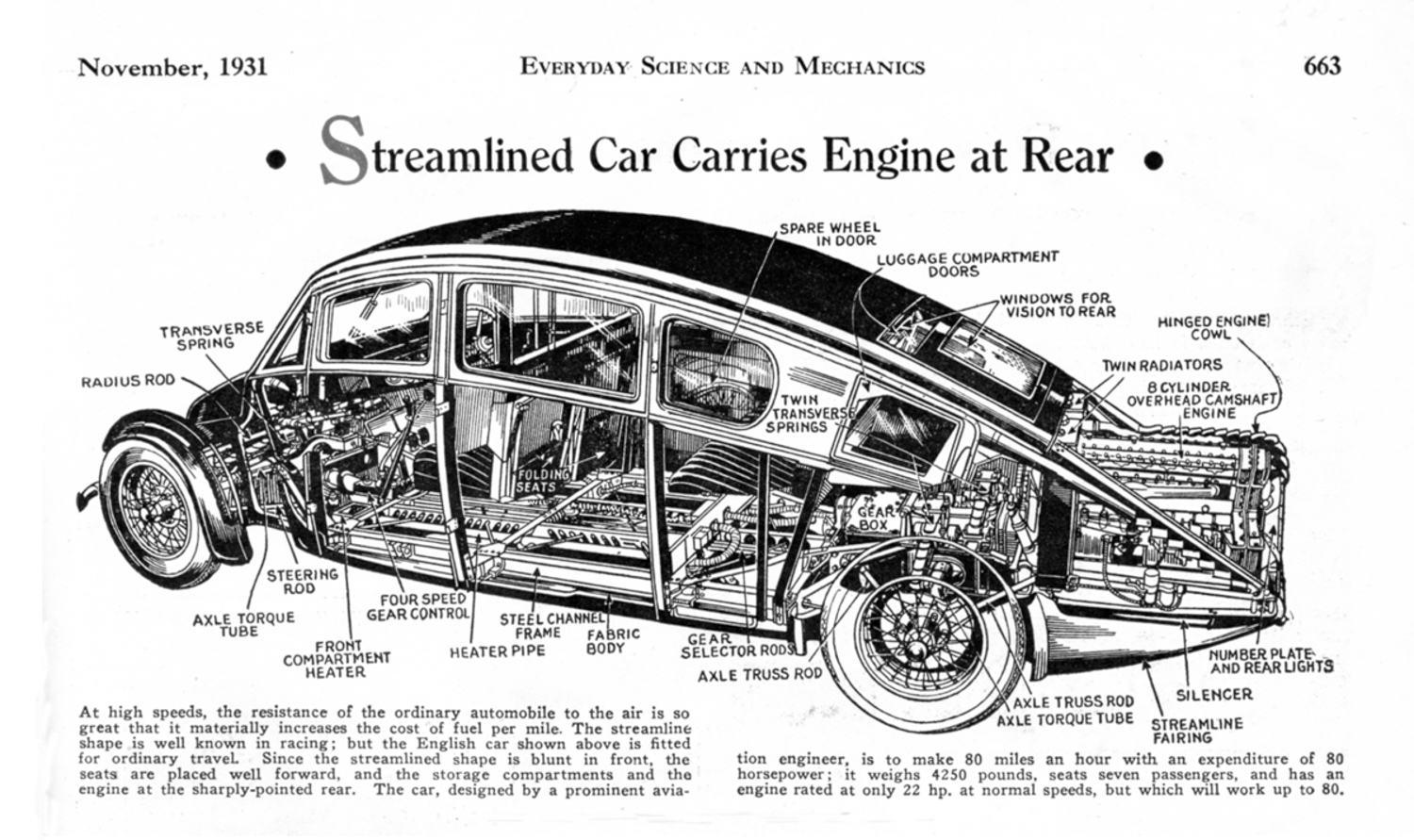

Edward Nicholas Cole was Chevrolet’s Chief Engineer, and he believed that there was a market for smaller cars. The Corvair would be different, though, so it would not take sales away from other Chevrolet models – its targets were the Falcon and Valiant and, especially, the VW Bug. Cole had a variety of experiences with and knowledge of rear-engined cars. He was familiar with the British Burney Car, Stout Scarab, and Tucker. He was experienced with driving a rear-engined automobile, having driven an experimental Pontiac coupe with a Cadillac V8 in the rear through a Detroit winter. He also had some experience with air-cooled engines, having been involved with the tanks GM built during and after WWII. The things that would make the Corvair so different than other American automobile products, were things with which Cole was comfortable.

Cole, in 1952, created a research and development department in Chevrolet. It was headed by Maurice Olley who had worked on the Cadet small car project. This department would be critical in the development of the Corvair. As work on the new small car began, Cole arranged with Harley Earl to have styling work done for the prototypes. By mid-1956, Cole had become the General Manager of Chevrolet, so the only person he had to convince about the car was Harlow Curtice, President of General Motors. Cole had experimented with a couple Porsches and Vauxhalls before developing the early Corvair prototype, named the Holden 25 in order to make anyone snooping around Chevrolet think it was a car designed for the Australian market. Cole showed Curtice the prototype and took him for a ride in it. Curtice, normally a proponent of big cars with the engines out front, gave his tentative approval for the project.

With Curtice’s approval, work on the final design could go ahead with deliberate speed. It had to be kept on a tight schedule, because work had already begun on the new Willow Run plant that would build the Corvair. Styling was a challenge. Early examples looked like shrunken big cars and were not satisfying, especially when sporting phony grilles in an attempt to hide the fact that they were rear-engined. Cole wanted a car with simple styling – light, economical, and fun. Cole, himself, was involved in the engine design. It would be a flat-six, a type of engine more common in aircraft than automobiles. For automobiles, there had been an experimental Mercedes Benz design in the mid-1930s, Leo Goosen’s still born DOHC, four-valve engine, and, the only one that reach production, Tucker. Cole’s design had two heads, six separate cylinder barrels, and a crankcase of two halves joined together.

There were some challenges. The engine was supposed to weigh 288 pounds but came in at 366 pounds or 78 pounds too heavy. That extra weight would be behind the rear wheels and affecting the design balance of the car. It was intended to be 40/60% weight distribution front/rear. After dealing with the extra weight of the engine, the distribution was 61.5% rear, 58.5% front – not bad. A final decision on the steering was to use recirculating ball with an 18:1 ratio and five turns lock to lock. That resulted in light but quite show steering. The rear suspension was a big issue, and there was a lot of experimentation with different designs. Chevrolet finally decided on using a swing axle because of:

- Lower cost

- Ease of assembly

- Ease of service

- Design simplicity

- Use of coil springs

- Reduced unsprung weight

- Isolation of the body from distortion stresses.

The decision to use a swing axle caused a lot of attention to tire sizes and pressures. A final decision was made in January 1959. The tires would be 650×13 and mounted on 5 ½ x13 rims – wider than stock Chevy rims. Tire pressures were recommended to be 15 psi front and 26 psi rear. This combination produced better handling and addressed the problem of snap oversteer often claimed about swing axle cars. Anti-roll bars might have helped, but they were eliminated to save $4.00 per car.

At first, Corvair was limited to a two-door coupe (700) and a four-door sedan (500), with the Monza (900) added later in 1960. Initial teething problems had some in Chevrolet wondering if the Corvair would last more than one year. But the car caught the attention of Zora Arkus Duntov who began working on performance improvements, including a performance cam and four carbs. Duntov was with five coupes that Chevrolet took to Daytona early in 1960 to compete against a variety of other “compact cars.” NASCAR ran a 10-lap and a 20-lap race for compact cars using the road course. Chevrolet assembled a group of serious racers for the Corvairs, which were equipped with the soon to be optional four-speed transmission. Drivers were Ricardo Rodriquez, Jim Reed, Jim Kaperonis, Ed Hugus, and Fireball Roberts. Despite the quality of the Corvair drivers, Plymouth Valiants trounced the field, led by Marvin Panch. Duntov was disappointed, but he apparently saw potential in this new Chevrolet.

Changes in Corvair models came almost annually. The first in 1960, were the 500 and 700, with the Monza 900 added later in the year. The Monza had bucket seats and was popular. The next year, Chevrolet added the Lakewood station wagon, in 500 and upmarket 700 form, and the Greenbrier van and pickup. The Lakewood was a good option for families, and the Greenbrier was a serious competitor for the Ford Econoline van. Both were short lived, with the Lakewood only lasting a year and a half and dropped when a convertible was added to the Corvair line in mid-1962 and the more conventional Chevy II wagon appeared. The Greenbrier, possibly because it was very innovative, was more expensive than the Econoline and was dropped after the 1965 model year.

The best and rarest of the Lakewood wagons was the Monza version. It was built only in 1962 and only 2362 were produced in the US and an additional 205 in Canada. The most unusual of the Greenbriers was a Corphibian, an amphibious Greenbrier pickup that never made it to market. It did make it to the Lane Motor Museum (www.lanemotormuseum.org) where it has been restored to cruising order on both land and water.

The big news for 1962 was not only the convertible, but the Spyder with its forced induction engine that upped output to 150 bhp at 4000 rpm. The engines had gone through some evolutions, with an increase in bore in 1961, upping displacement by 5 cubic inches to 145 cid, and an increase in stroke in 1964 resulting in an engine of 164 cid. Improvements to the car’s suspension began in 1962 with optional stiffer springs, shorter limiting straps, and a front swaybar. There was a major improvement in 1964 when Chevrolet added a rear camber compensating spring.

There were more important engine improvements in 1965 when the engines received larger valves and ports and four carburetors with a progressive linkage. But that was hardly the most important change for 1965. The original Corvair styling had been much copied by Simca (1000), Renault (R8), Fiat (1300), and NSU (Prinz). Chevrolet had achieved its goal of a car whose styling was smooth and simple. The 1965 Corvair was a very different car than its earlier siblings. It was hot! It was a very attractive car, and its handling was much improved. It looked as though Corvair had an excellent future. So Chevrolet killed it.

The Corvair was originally intended to be an inexpensive, economical family car, a good second car for a family in the suburbs; a car for the wife to drive while the husband commuted to work in his Impala or Oldsmobile 88. The Corvair, though, had evolved, and its most popular versions had put the car squarely in the specialty market. In 1965, Corvair might have owned that market but for the mid-1964 release of the Ford Mustang. The Mustang was available with either a six- or eight-cylinder engine and had a list of options that allowed the car to be anything from an economy car to a street racer. It overwhelmed the Corvair at a time when GM was expanding the Chevrolet line to include the Chevy II, Camaro, and Chevelle. The decision at GM was to continue to produce the Corvair but there was to be no additional development except to meet the new federal crash and emissions standards.

As it became obvious that GM was going to drop the Corvair, Road & Track magazine published an open letter to Chevrolet in February 1968 asking that the Corvair be continued as a new GT car. There had been quite a lot of interest among coachbuilders and others who saw potential for a sharp looking American GT. Chevy styling had developed versions of the car, such as the Monza GT that could have rivaled anything produced in Europe. Pininfarina and Bertone with did prototypes and show cars based on the Corvair. Sadly, the Corvair was put to rest after the 1969 model year. The last Corvair was a Olympic Gold coupe that rolled off the line at 1:30 pm on May 14, 1969.

Corvariations

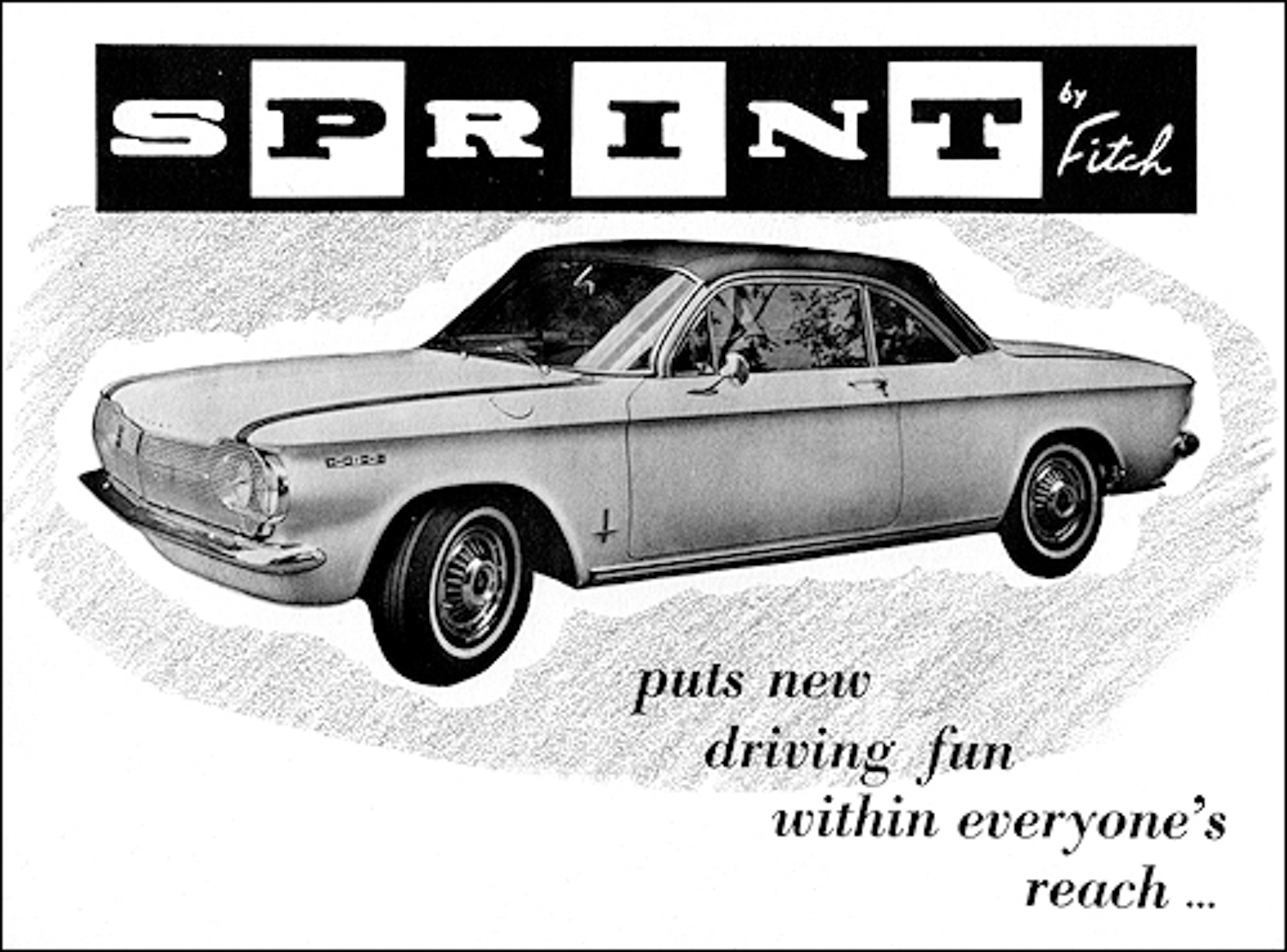

The Corvair was a popular basis for people, especially racers, who wanted to develop a unique sporty car. Dick Griffen used a Corvair as a basis for his supercharged drag racer. Doug Roe built a special hillclimb car from a 700 coupe. Racer and inventor John Fitch used the Corvair as a basis for his own cars, the Fitch Sprint and swoopy Phoenix.

John Cooper Fitch was a well-known American racer who drove for Briggs Cunningham, Mercedes, and a number of other teams. A poster made in his honor in the early 2000s is a collage of 47 photos of cars that he drove. Fitch was very involved in developing safety devices both for racing and highway driving. One of the most visible of his designs is the Fitch Barrier – the yellow, sand filled plastic barrels sometimes still seen at bridge abutments providing protection for errant drivers who have for whatever reason decided to crash into the abutment.

Fitch liked the Corvair and the way it handled. The first Fitch Sprints were modified 1964 coupes and convertibles. Modifications were made for performance and looks on the Sprint. A new four carburetor head gave the Sprint a boost to 155 bhp making it noticeably faster. Metallic brake shoes made it stop better. Better shocks, springs, and wheel alignment meant the car handled better. A rosewood shift knob and subtle racing strips, among other little things, made it look better. A mesh metal stone grill on the nose was probably the one thing that immediately made the Sprint recognizable. The later Sprints, based on the new Corvair design introduced in 1965, had an even more distinct look. Spoilers were added to the list of options, but the most distinctive option was the “Ventop,” which when added to the C-pillars and roofline, gave the car a flying buttress look. Fitch built a prototype of his ultimate automobile, the Phoenix, based on a Corvair with a 170 bhp Weber carbureted engine. The design was reminiscent of the Corvette Mako Shark prototype – very sleek. Unfortunately, Fitch’s dream took two significant hits. The Traffic Safety Act of 1966 put serious restrictions on the production of small runs of cars, and Chevrolet decided to end production of the Corvair in 1969. Only the one prototype Fitch Phoenix exists.

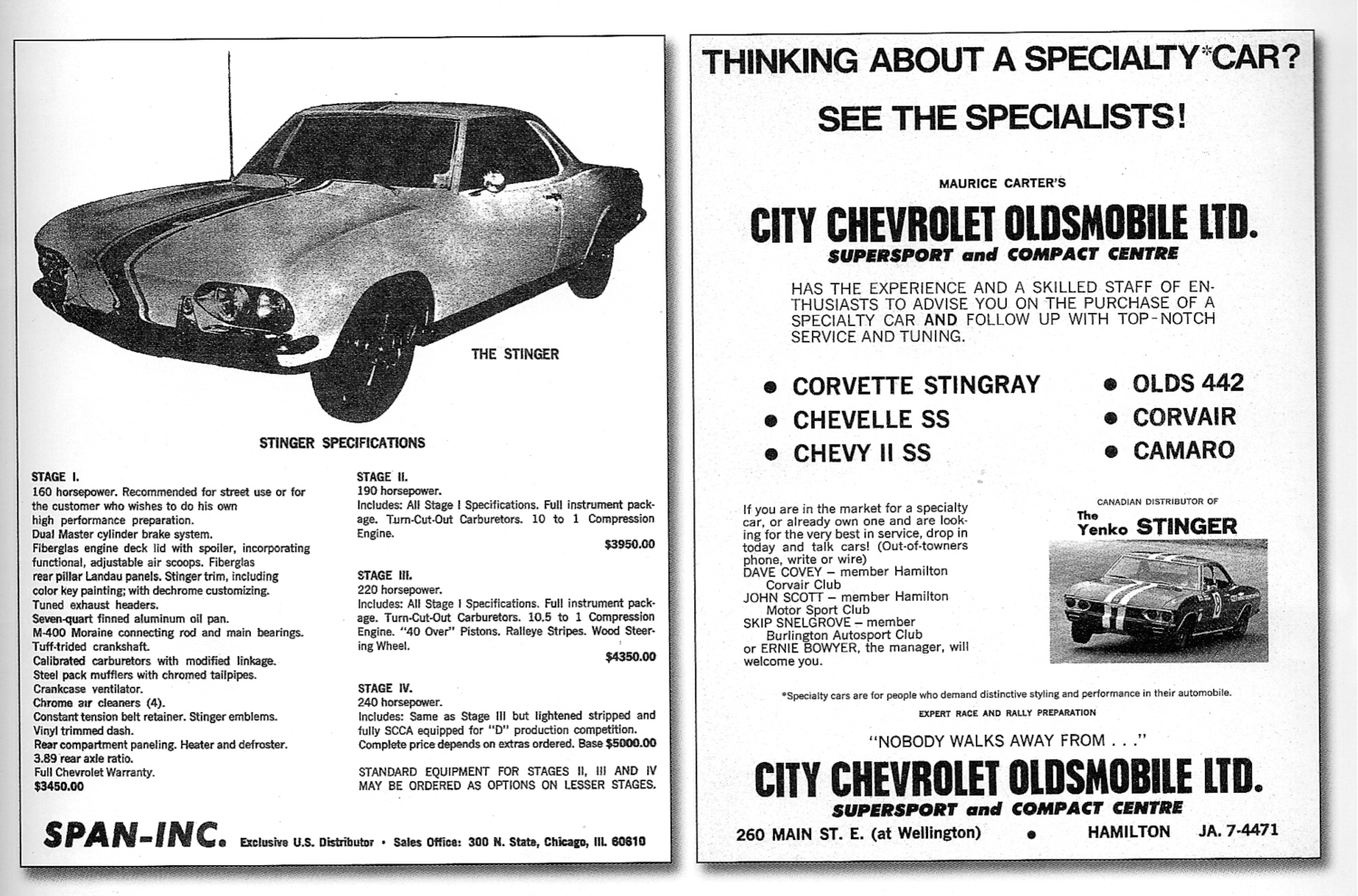

Don Yenko and His Stingers

The most successful of the Corvariations was the Yenko Stinger, built, mostly, by a Chevrolet dealer in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. Donald Frank Yenko was an interesting guy. Born in 1957 in Monongahela, Pennsylvania, in 1927, he was enthusiastic about flying, jazz keyboard, and sports car racing. His father managed a car dealership where his mother kept the books, so it is understandable that he entered into the same business. His interest in racing started early, competing in soapbox derby in a racer of his own design. His choice of racecars as an adult was the Corvette. Yenko operated a race shop preparing Corvettes from 1958 to 1961. He raced Vettes in the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) during the 1950s and 1960s and was B Production National Champion in 1962 and 1963. Between 1962 and 1986, he raced at Sebring nineteen times and at Daytona nine times.

Small block Corvettes were the cars to beat in SCCA B Production until Shelby got involved with the Mustang. By 1966, Corvettes were no longer the car of choice. Yenko had raced Corvairs in a twelve hour race at Marlboro Raceway in Maryland, so he was familiar with them as potential race cars. He was also an early dealer for the Fitch Sprint, so he knew about the modifications Fitch made to gave the car better handling and performance. Yenko was familiar with Central Office Production Orders and was certain that he could build a second generation Corvair using COPO parts that would be a better sports car than the Shelby Mustang.

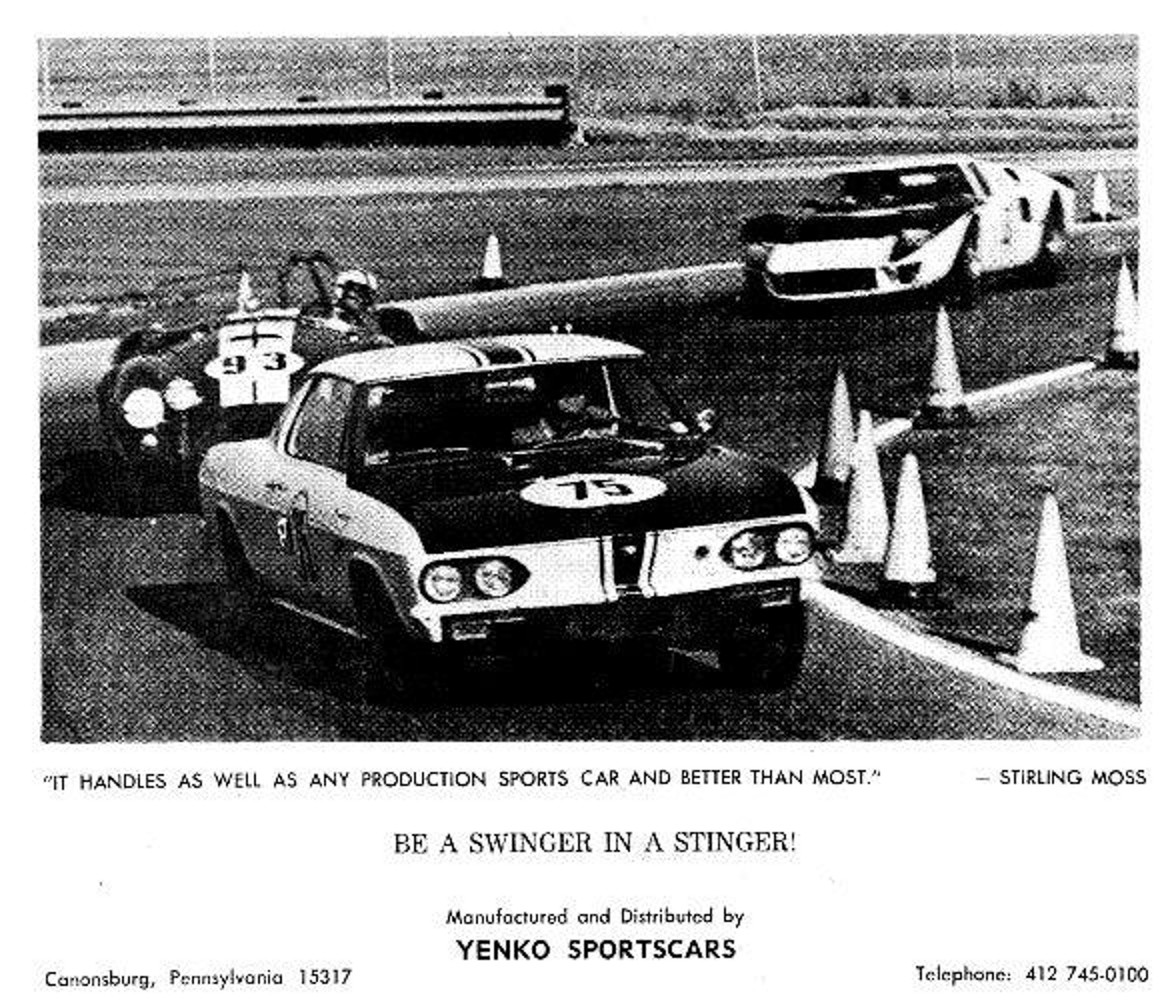

Yenko approached SCCA about having his planned Corvairs approved for racing in 1966. SCCA gave a tentative approval in November 1965 to the concept as long as Yenko could build 100 cars for inspection and homologation. Yenko ordered 100 ermine white 1966 Corvair Corsas with black interiors, four-speed transmissions, quick steering, positraction rear end, and heavy duty suspension. Half of the cars were ordered with a 3.55:1 final drive; the other half came with 3.89:1. There was a serious flurry of activities to get the 100 cars built in time for SCCA’s inspection in January 1966, a month away. Joe Pike, from Chevrolet, helped by giving the car its name – “Stinger” – since the engine is in the rear like a bee’s stinger. Grady Davis, the Vice President of Gulf Oil let Yenko develop the engine at Gulf Research. John Salathe, a designer for Alcoa Aluminum, helped with the body design. Pizza boxes, probably from feeding the development crew during their late night work, were cut to mock up the rear spoiler, side windows, sail/landau panels (to make the car look like a two-seater), and “cool air” doors (to add air flow to the engine). Yenko somehow managed to arrange for Stirling Moss to test the prototype at Marlboro Raceway (1.8-mile, 10-turn course). Moss remarked afterward, “It handles as well as any production sports car, and better than most.”

SCCA representatives inspected and approved the 100 Stingers on January 6, 1966. Yenko had hoped that the cars would be classed in either G or H Production, but SCCA put then in D Production, a class dominated by Bob Tullius and his TR4s. The decision was probably based on the performance of Corvairs in SCCA sedan classes. Based on the results of Stingers in SCCA competition, it appears to have been properly classed in D Production.

Yenko’s intent was to create both road and race cars, so the decision was to build cars to five different stages of tune:

Stage I – street use

- 160 bhp

- Mostly bolt-on components

- Available from Chevrolet dealers

Stage II – High speed touring, rallying, dual-purpose race car

- Engine modifications to produce 175 bhp

- Hotter camshaft

- 10:1 compression

- Carburetors modified for hard cornering

Stage III – For SCCA D Production

- Engine rebuilt to special specifications to produce 210 bhp

- Even hotter cam

- High performance cylinder heads with enlarged and matched ports

- 5:1 compression

- Carburetor modifications for competition

- Lightened, balanced flysheel

- Baffled oil pan

- Balanced cranksaft

- Tuned velocity stacks

- Reversed exhaust headers

- Electric fuel pump

- Metallic brakes

- 13×7” reinforced wheels with either Goodyear or Firestone race tires

- Roll bar

- Competition harness and belts

Stage IV – Not legal for SCCA D Production

- 176 cid engine

- 185 bhp with Stage II modifications

- 230 bhp with Stage III modifications

Stage V – Ultimate power car for off street driving

- Stage III plus fuel injection

- 250 bhp

Only two of the Stage V cars were ever built. Both were built for racer Jerry Thompson for a 1966 sedan race at Mosport in Canada. The race was run to FIA Group 4 rules.

The first race for Stingers was the “Refrigerator Bowl” at Marlboro on January 8-9, 1966, only days after SCCA approval. Jerry Thompson finished third to Tullius and Dick Stockton, both in TR4s. The other car suffered clutch problems and did not finish. Next up was the 24 Hours at Daytona. One Stinger and one Corsa were entered. The Corsa was in the GT class, but the Stinger was in P+2.0 – sports prototypes over 2-liter displacement. The Stinger was 37th on the starting grid and managed a 29th place finish overall. More impressive was its 9th in class behind four Ford GT Mk IIs, a Ferrari 365 P3/4, and three Ferrari 250 LMs. There were two Stingers at Sebring in March 1966, but neither finished.

SCCA racing got underway seriously after the Florida endurance races. Several drivers of Stingers did well enough to be invited to the Runoffs, SCCA’s national championship races. At the Runoffs at Riverside in 1966, Jerry Thompson finished fifth in D Production, with Dr. Dick Thompson, the racing dentist, suffering a DNF. Jim Spencer entered his Stinger as a D Sport Racer and took home the silver medal. The Runoffs in 1967 were held at Daytona, and it was a very rewarding event. Jerry Thompson borrowed the fifth built Stinger from Yenko and made some adjustments to better suit the banking at Daytona. First, Thompson changed the rear end ration from 3.89 to 3.55, but it was still too high. After a search, he found a 3.27 differential at a dealership in Louisville, Kentucky, installed it, and broke it in on Saturday night. In the D Production race, Thompson dominated the field and won the first, and, sadly, the only championship for a Yenko Stinger. Don Yenko was so pleased with the result, he paid the expenses for the crew and gave Thompson the car.

That was the last appearance of a Stinger at the Runoffs for five years, but there were plenty racing successes. Stinger drivers won ten SCCA Divisional Championships between 1966 and 1995 in three classes – D Production (seven Championships), D Sports Racer (one Championship), and GT3 (two Championships after the car was reclassified as a GT rather than a Production car.) At the Runoffs, there were nineteen finishes in the top ten between 1966 and 2000. Five of those finishes, the most by any Stinger driver, were by Jon Brakke. Brakke changed classes in 2001 and raced an E Production Mazda Miata to three National Championships.

Stinger drivers also competed in SCCA solo and rally competitions in the 1980s and early 1990s. Between Solo I and Solo II, Stingers were driven to fourteen championships. Charlie Clark won a total of eight championships, four in each category. Liz and Suzanne Berger had five championships between them in the Ladies category in Stingers. There was one rally championship, won by Emmy and Pete Dunkle. Stingers can still be found in vintage racing series.

With an even 100 cars in the initial fleet purchase, it would suggest that identifying the original Stingers could be easy. It is, mostly. The VIN of the first hundred cars range from 107376W130567 to 107376W132422. Yenko gave them Stinger serial numbers YS001 to YS100 on tags affixed to the driver’s door pillar, although the numbers weren’t assigned sequentially, so there’s a little confusion about the order in which they were produced. Somewhere along the line YS084 became YS191, for an unknown reason. Then it gets a bit worse. In 1967, Yenko placed another fleet order for 25 Monza Coupes, as the Corsa had been discontinued. This time there would be red, blue, and green Stingers in addition to white. These had VIN numbers from 105377W120086 to 105377W120136. Eight to eleven of these cars were sold as ’67 Monzas, so not all 25 cars became Stingers. Those that became Stingers were assigned number from YS101 to YS199. It is believed that YS001-105 were built by Yenko Sportscars in 1965 and 1966, and YS106-199 were built between 1967 and 1969, although not all those numbers were issued. There is one four digit Stinger number, YS9700, for a car built in 1969. Rumors of a YS8399 and YS8900 have not been confirmed. Donna Mae Mims, Yenko’s assistant and secretary, said there were eight duplicate tags made in error. Attempts were made to correct the error without success. There are no tags with Stinger number between 200 and 299. But there are cars with Stinger tags from YS300-YS320. Owners of early Stingers tend to disregard these later tags, since they are on cars that were not built by Yenko but were tags provided to owners who modified their Corvairs to be Stingers or had them modified at dealerships. In 1971, Yenko had an extensive “Yenko Stinger Stuff, Hi-Po Parts Catalog.” If you wanted to build your own Yenko Stinger, all the parts were available from Yenko Sportscars, and you could purchase a Yenko tag and serial number once you were done.

All of the early Stingers were white with a wide blue central racing stripe with a smaller blue stripe on each side. Well, most of them were. Bob Dunahugh, owner of four Stingers, has a red one, and he related the story behind it. A potential buyer arrived at Yenko Chevrolet and told Don Yenko he wanted to buy a red Stinger. Yenko replied that all Stingers were white with blue stripes. The potential buyer continued to insist; Yenko continued to refuse; and the argument got heated. Mims, who was listening, intervened, and told Yenko that there was red Corvair on the lot and to just build it for the guy. Mims could apparently be assertive, possibly a trait that helped her to win the first SCCA National Championship by a woman. Yenko relented and built the first red Stinger, now in Dunahugh’s possession.

When Chevrolet killed the Corvair, it ended the Yenko Stingers, although it didn’t keep Yenko from modifying other Chevrolets. There are Yenko versions of the Camaro, Chevelle, Nova, and even the Vega. Yenko closed his dealership in 1982 and died a few years later while piloting his small plane, crashing while trying to land. About Yenko, Zora Arkus Duntov said, “He was a good man, and maybe more importantly, he was a happy man.” Yenko rode in a race car one more time, his ashes were carried in a car competing in a 1988 Firestone Firehawk 500 kilometer race.

YS320

Serendipity is very important in this business of writing about interesting automobiles. Sometimes an opportunity just appears, and you have to take advantage of it. I’d been wanting to do an article on Corvairs, a car that I have long thought to be under appreciated. I felt the best avenue for that was to profile an exceptional Corvair, like the Yenko Stinger. Finding one was the issue. While attending a convention of the Alfa Romeo Owners Club in Pittsburgh, I spent some time at the track event. I was photographing a few Alfas running the autocross when a motor home pulled in to the track towing a Yenko Stinger on its trailer. I abandoned the autocross and chased the motor home until it stopped in the track’s paddock. There I met Russ Rosenberg, who had towed his Stinger from Texas for the Pittsburgh Grand Prix weekend. We talked, and I had my subject for the profile. The intent was that we’d meet when he was in Birmingham, Alabama, for vintage races in 2020. Enter covid-19 and the cancellation of nearly every event where Rosenberg and I might meet. My Corvair article became the first profile of a significant car I have ever done remotely. Thanks to Russ Rosenberg and his excellent talent for writing, we have this profile.

Rosenberg picks up the story: “My car, which holds Tag YS320 began life as a garden variety 1965 Chevrolet Corvair. My journey towards Stinger ownership began in 2012, while racing my BMW 2002 at Road Atlanta for the HSR ‘The Mitty,’ I was passed by Rick Norris in his Sunoco Livery Corvair racecar. Rick, who I didn’t know at the time (but do now), blew by me quickly and I was really surprised having always thought of Corvairs as slow and lacking grace. That weekend didn’t end well for my BMW, a blown motor cutting it short. On the long drive of shame back to Texas, I started thinking about my next racecar. Why not a Corvair?

“Fast forwards a couple of months, and I couldn’t get Rick’s Corvair out of my mind. I ran across a project car for practically nothing, a $500 1965 Corvair that was complete but inoperative in a neighboring town. I dragged it home and began a 2 year strip down and build to make a race worthy car. Remember, I had still never driven a Corvair.

“About the time I had finished the tear down and body prep, my good friend Chris Langley, a long time Corvair expert and owner of Yenko Stinger YS-199 let me take his car out at Texas World Speedway for a 15 minute session of hot lapping. I was hooked. With a lot of guidance from Chris, and later Jeff ‘Jefmo’ Moore, owner of Automotive Archeologists, Ltd, over the next year I built a very competent Corvair racecar. In 2017, I acquired the YS-320 Yenko tag in a super secret transaction that made my car the last Yenko.

“YS320 first hit the race track with a temporary engine while JefMo was building my motor. Two temporary motors later, we had the Jefmo motor in place. Corvair motors are 2.7L (164cc) 180-degree, 6-cylinder opposed air cooled, pushrod motors. Think Porsche 914 with 2 more cylinders. [They are] somewhat rev limited at 6500-6800 rpm – revving higher dramatically shortens the life, as with mostly 50 year old crankshafts strange harmonics tend to break the crank between the 5th and 6th cylinder. Coupled to a stout Saginaw 4-speed Transaxle, with a LSD in most cases, the driveline is strong and reliable. Shift linkage is a rod that travels from the gearshift to the transaxle and requires a lot of fiddling to work just right. Since the business end is in the back and the controls are in the front, everything is operated by rods, cables and bushings which have to be right to be effective on the race track, or the street.

“While building the eventual YS320, I wanted to do things the way I would feel most comfortable. Having much of my background in German cars, I preferred floor pedals and a hydraulic clutch. I was determined to build the car to fit me while staying within the rules of the sanctioning body (SVRA) that I wanted to compete in. Luckily things like controls and other things allowed for a great deal of flexibility.

“The Corvair suspension in stock form is surprisingly good. With independent rear suspension, the proper shocks and spring rates and sway bars, a late model (65-69) Corvair can be made to be hard to match in handling for anything that was made in America from the 1960’s. The added bonus is that with the weight over the drive wheels, the long wheelbase make the Corvair brilliant in the rain.

Racing YS320

“With the support of Chris, JefMo and others I was able to get the car on track in February 2016. After a difficult first year struggling through the aforementioned temporary engines, year two began the real development curve for the car. It was about this time that I acquired the YS320 tag, and my car assumed its identity, much the way any Yenko tag over number 132 was issued.

I first ran my Yenko Corvair in April 2018. Newly installed with the JefMo motor, YS320 was transformed into a well-balanced race car. Yenko Stingers are not like most race cars. Properly tuned and set up, it has incredible balance if not incredible power. A momentum car, it rewards a prepared driver. A Yenko can be pushed to its limits and beyond but as with most momentum cars, staying on the throttle is rewarding.

“The best way to describe the car when racing is [that] a high level of commitment is needed to get the most out of it because of weight and mediocre acceleration compared to a 911 or a B-Sedan. My favorite comparison to my B-Sedan BMW 2002 is that the BMW is light, accelerates quickly but is twitchy. The Yenko feels planted – almost planted in the track (as opposed to on it), and, because of the long wheelbase, abrupt changes don’t work as well as the BMW. With experience, you can ring its neck like any other race car, but you really have to plan with the gearbox because shifts are not quick and snicky like the BMW, which has a close ratio custom 4-speed. No double clutching needed but much less flexibility on most tracks with gear selection. A Yenko can be taken to its limit and beyond on cornering, understeer is only an issue if your front tires are trash or over inflated. I run radials so when the back end starts to slide, it is time to make adjustments. Wheel sawing is really not needed as you can steer with the throttle [a bit], and the long wheelbase keeps things somewhat linear. If you do lose the back end in a turn, it can snap, but my experience since the car was properly corner weighted and adjusted is you really have to overdo it for that to happen.”

Rosenberg has enjoyed racing his Yenko Stinger. He races often with Corinthian Vintage Auto Racing in Texas and Oklahoma, where he frequently wins in D Production. He has raced nationally at Barber Motorsports Park and at the Pittsburgh Grand Prix. At PittRace Feature Race, he finished 19th overall (of 36) and fourth in class. His was the first Yenko Stinger ever to race on the very tight Schenley Park course, which favors small cars. His finish was 23rd of 32. At Barber, he was third in class and 16th overall (of 29) in the first race and suffered a bearing failure in the second race.

It has been quite an experience writing a profile in the days of covid-19. Rosenberg made it possible to do this remote profile by providing words and photographs. Photographs of his car on track were taken by Bill Stoler and made available to Rosenberg for this article. Other photos of the Stinger were taken by him or his wife. Thank you, Russ, for your considerable help, including the loan of the very rare book by Charlie Doerge.

Initially, it was my intent to write a history of the Corvair, a model I snubbed when it was current but grew to respect with time. The article became a mission thanks to the enthusiasm for Corvairs of my good friend David Allin, current president of Corvairs of New Mexico. He arranged a photo shoot of members’ cars as I was developing the concept for the article. Thanks also to the club members who brought their Corvairs to the shoot – David Huntoon, Robert Gold, Terry Price, as well as David Allin. When chance brought Rosenberg and me together in Pittsburg, the history article became this profile.

In his Automobile Quarterly article, Ludvigsen wonders, “Only time will tell whether or not the owners and admirers who were so enthused about the Corvair in life will still wish it well now that the last model has been sold complete with a certificate good for $150 against the purchase of a new 1973 Chevrolet.” It’s hard to tell how many Corvair buyers in 1969 used that $150 certificate, but, from my experience in writing this profile, there are plenty admirers and enthusiasts still enjoying their Corvairs.

Specifications (YB320 Current)

| Body | Unit body Corvair Monza with Yenko modifications |

| Chassis | Steel, Corvair Monza chassis |

| Engine | Rear mounted horizontally opposed six cylinder |

| Displacement | 3081.4 cc/188.0 cid (0.040 inch overbore from stock) |

| Bore/Stroke | 3.44 inches (87.4 mm)/2.9 inches (75 mm) |

| Induction | 2 – 3 bbl Weber 40IDA carburetors |

| Power | 175 hp/130.5 KW dynode at rear wheels |

| Compression ratio | 10.2:1 |

| Transmission | 4-speed double close ratio with custom gear set |

| Height | 50.5 inches/1282.7 mm |

| Length | 183.3 inches/4656 mm |

| Width | 69.7 inches/1770 mm |

| Wheelbase | 108.0 inches/2743 mm |

| Front Track | 55.0 inches/1397 mm |

| Rear Track | 56.6 inches/1438 mm |

| Weight | 2308 pounds/1046.9 Kg |

| Steering | Recirculating ball |

| Suspension | Factory heavy duty suspension with reinforced cross member, trailing arms, poly bushings, Crown Swaybars, Gaz adjustable shocks |

| Brakes | Front GM period Disc and rear drum with metallic linings |

| Wheels | 15×7 |

| Tires | Hoosier Speedster 225/45/15 |