Known more for his mercurial temper than his victories over the likes of Carraciola and Nuvolari, prewar Italian driving star Luigi Fagioli still ranks as one of the great unsung heroes of racing’s Golden Era.

In this the final instalment, Robert Newman chronicles the final years of his career including a unique Grand Prix record that is likely never to be broken.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

The hot-blooded Luigi Fagioli was a qualified accountant whose family was in the pasta business. An unlikely launch pad for a Grand Prix winner, yet after a brief dalliance with motorcycles, he shoved his foot in the motorsport door at the somewhat advanced age of 27. Fagioli began competing in modest local events in 1925, driving his own 1,100-cc Salmson, which was the state-of-the-art small displacement racing car of the day. He later bought an eight-cylinder 1,500-cc Maserati, with which he won provincial races like the Coppa Principe di Piemonte and, further up the ladder, the Coppa Ciano. The Tough Guy’s first break came when he was offered a works Maserati 26 M, with which he won the 1931 Grand Prix of Monza and beat the likes of Tazio Nuvolari, Achille Varzi and Louis Chiron in the process. Fagioli and his works Maserati spent much of the following year coming 2nd and 3rd to the Flying Mantuan’s factory-entered Alfa Romeos and that did not go unnoticed. In 1933, he took over from a disgruntled Nuvolari at Scuderia Ferrari, and the Tough Guy proved his worth by winning the year’s Coppa Acerbo, the Grands Prix of Comminges and Italy in the Scuderia’s Alfa Romeos. As he did so, he inflicted another defeat on Nuvolari and won his first Italian Championship. Fagioli had arrived, big time.

Alfred Neubauer and Mercedes-Benz were short of good German drivers for 1934: the fearsome team boss’s friend and future triple European Champion, Rudolf Caracciola, had been cut down by a crippling accident while practicing for the previous year’s Monaco GP and had lost his wife after a tragic skiing accident. Manfred von Brauchitsch and Ernst Henne were insufficiently experienced to lead the team. Driving talent was thin on the ground in Germany at the time, so Stuttgart looked further afield for their top racer. Neubauer spoke no Italian, but still engaged the Abruzzi Robber, as they called Fagioli—and that was the start of an explosive coexistence, which often erupted into slanging matches neither could understand. Fagioli, who spoke no German, considered himself Mercedes’ number one, but he could not get out from under the politics of motor racing for the Third Reich. He would only be allowed to win if a German driver was unable to do so. And that made the Tough Guy even tougher. Merit was merit, and it was certainly not to be smothered by drivers of a lesser God.

It did not take long for things to come to a head: soon after Fagioli had joined Mercedes and the 1934 season had got under way, he had already shown he would not knuckle under to team orders and would rather abandon a race than let a slower Mercedes driver pass him for victory. As the year wore on, Caracciola began to recover from his literally crippling accident at Monaco a year earlier and, towards the end of ’34, he was challenging Luigi for victory on more or less equal terms, much to Neubauer’s satisfaction. Caracciola was leading the Grand Prix of Spain at San Sebastian—the penultimate GP of the season—by a country mile, so Neubauer gave him the order to ease his pace, expecting Fagioli to hold station in 2nd. But there was no way the Tough Guy was going to stand for that, so he reeled in Caracciola, overtook him and went on to win the race. Apoplexy in the pits ensued.

Photo: Daimler Chrysler

But even after an embattled 1934, Fagioli resigned with Mercedes for 1935. It was obvious that even more sparks were going to fly during the new season, but, with Caracciola still on the mend, Stuttgart needed the Italian’s race-winning capability and Fagioli knew the Silver Arrows were going to be the cars to beat.

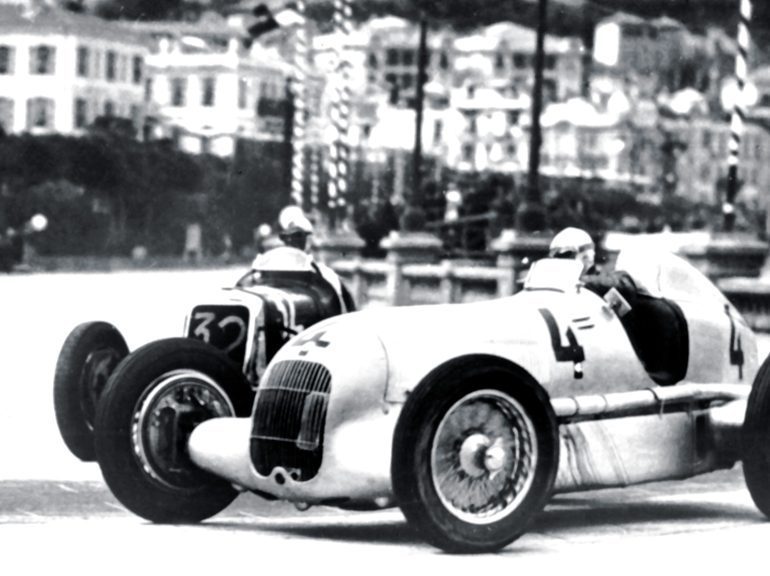

Luigi got them off to a good start at the first round of the first European Championship on May 22, 1935, in Monaco, where the 36-year-old Italian won and became the first driver to lead at Monte Carlo from start to finish. Caracciola, who was in less pain and driving well that year, took Tripoli, where the Tough Guy only managed 3rd. Fagioli convinced himself he badly need- ed another win, which came his way on the ultra-fast Avus autobahn circuit near Berlin, but he could only make 4th in the Eifel Grand Prix which followed.

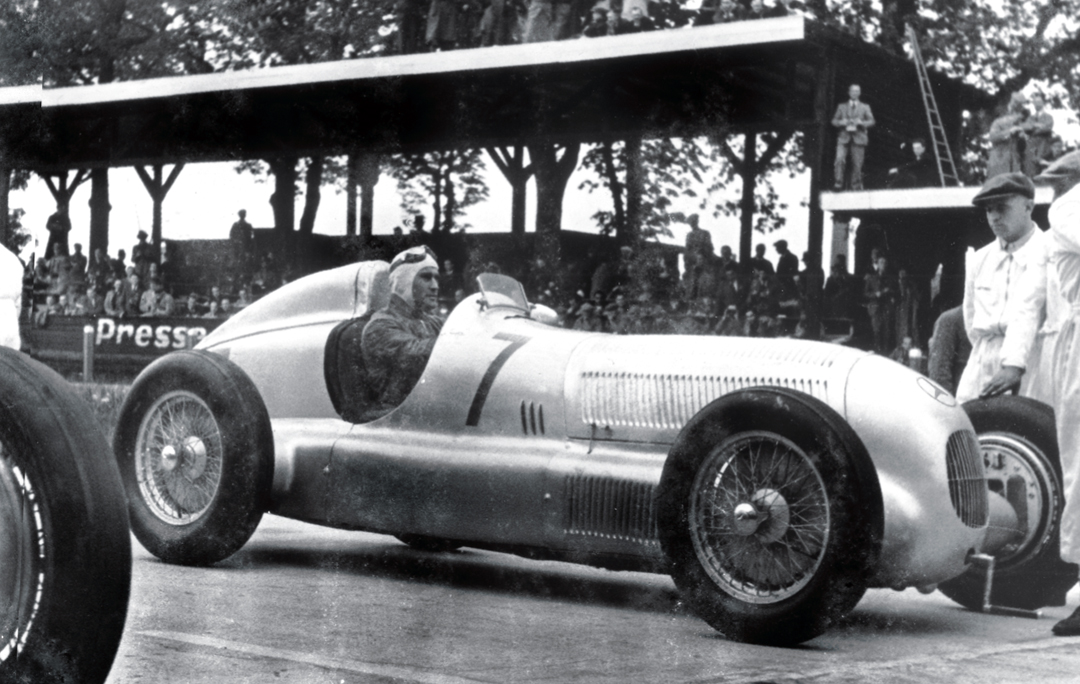

Next up was the French GP. Caracciola was firmly in the lead at Montlhéry and saw no reason to tempt fate by pushing his car too hard, so he slowed but stayed in command. Fagioli saw what was going on, sped up and slipped past the German into the lead. But Rudy was not having that and decided to give the unruly Italian a piece of his mind. He pulled level with Fagioli on the straight in front of the stands and the two started to harangue each other wheel to wheel at more than 80 mph, waving their arms in the air. The gentlemanly British magazine “Motor” reported them as “apparently exchanging light after-luncheon conversation,” but it was a tirade that went on for several laps as they howled past the stunned spectators, until Fagioli’s W25B slowed with plug trouble. That left Caracciola free to cruise to victory and Luigi spluttering to a distant 4th, three laps down.

Photo: Daimler Chrysler

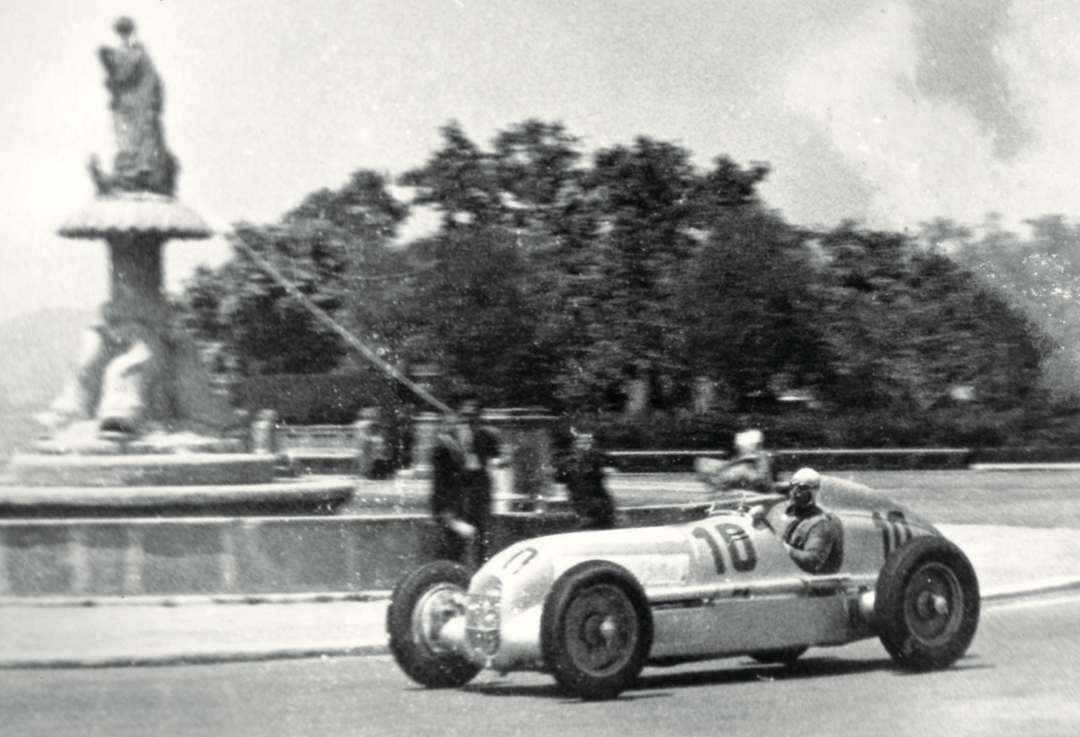

Fagioli swore he would win the following Grand Prix of Penya Rhin, come what may. So, not surprisingly, the Barcelona circuit was the scene of another violent Fagioli-Caracciola clash as the two duked it out for more than 40 laps. Rudolf took the lead on the 43rd, relegating Fagioli to 2nd again: Alfred Neubauer astutely chose that moment to signal “maintain your positions” from the pits. But Fagioli rebelled again. He eased his Mercedes past Caracciola to take com- mand and victory. An enraged Neubauer resolved to stop this embarrassing disobedience, but as far as Fagioli knew, he had got away with it again and he was spoiling for more.

Fagiloi and Caracciola were at each other’s throats again two weeks later, during the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, where Caracciola led from the start with Fagioli and von Brauchitsch giving chase. Brauchitsch went out with engine trouble, so Fagioli put the pressure on Caracciola by setting one lap record after another. The German kept the quicker Italian bottled up behind him for several laps and, predictably, Fagioli was fuming. Now it was his turn: the Italian repeatedly drew level with Rudolf at the La Source and Stavelot hairpins and down the hill past the pits, so that he could hurl incandescent abuse at Caracciola and emphasize his protests with much fist shaking. That was it: Neubauer lost his patience with the Italian and signaled him to come into the pits, where Luigi and his boss had yet another screaming match. That finished Fagioli for the day: he had had enough and stomped off, cursing as he went. So von Brauchitsch was told to take over Luigi’s abandoned W25B, which he brought home in 2nd place behind the victor— Caracciola.

Photo: Daimler Chrysler

The running battle continued at a rainy Swiss GP in Bern, but with a new twist. Neubauer and Caracciola had worked out a simple plan of defense. Der Regenmeister was in his element in the wet and set the pace. Even so, Fagioli was not going to be done out of a chance of challenging the German for the lead again, so he upped his rhythm. That was when the pre-agreed Neubauer-Caracciola defensive mechanism went into operation. The Mercedes pits kept Caracciola well informed of Fagioli’s progress, so that the German could speed up when necessary to keep the Tough Guy at bay. The Regenmeister had lost none of his wet weather magic, so the end-of-race results board read Caracciola 1st, Fagioli 2nd. The Italian was beside himself.

Surprisingly, all the Mercedes dropped out of the Italian Grand Prix with an assortment of problems, but they were back in command at the Grand Prix of Spain near San Sebastian, the final race of the season: as in previous races Caracciola won, Fagioli came 2nd and von Brauchitsch 3rd.

The-end-of year tally confirmed that Carraciola was back in fighting form, with six victories to Fagioli’s three: and the cars from Stuttgart had notched up a total of 11 GP wins. On top of that, Rudolf Caracciola had won the first of his three European Championships, the forerunner of today’s Formula One world title. The Tough Guy was an unhappy man.

Photo: Daimler Chrysler

Auto Union had their best year in 1936, winning 6 out of a possible 12 Grands Prix, although Tazio Nuvolari made Bernd Rosemeyer work hard for his European Championship by taking Alfas to victory four times, as well as winning $84,000 and the huge Vanderbilt Cup. Before the season had got under way, Alfred Neubauer had wrestled with the notion of getting rid of his troublesome Abruzzi Robber, but he had to admit he needed the Tough Guy’s skill and maturity, if not his rebelliousness. On another note, the German team boss had let himself be talked into hiring Louis Chiron by the new European Champion, but that did not work out. The Monegasque driver had little impact on Grand Prix motor racing that year.

The best Mercedes could do was to win at Monaco and Tunis (Caracciola) and all that Fagioli could manage that year was a 3rd at Tripoli, a joint 5th with Caracciola in the German GP and a 4th with Hermann Lang (an ex- mechanic and new recruit who was much resented by the established Mercedes “nobility” of Caracciola and von Brauchitsch). However, by this time Fagioli’s rheumatism was plaguing him and it was starting to affect his driving. The Stuttgart team decided to withdraw early from the championship, giving the Italian GP and the Vanderbilt Cup a miss. They needed better technical input, so they brought in 33-year-old Rudolf Uhlenhaut from road car production: his touch of magic put Mercedes back on the road to racing success in 1937 with the W125.

Fagioli had had enough of Neubauer favoring Caracciola, who was firmly entrenched as Mercedes-Benz’ number one. After yet more heated arguments with the German team manager, the Italian decided it was time to go. But where? He was 38 years old and his rheumatism was becoming a real problem. He wanted to retire from motor racing in a blaze of glory and after its stunning 1936 season, he felt Auto Union was his best bet—even if it did boast the explosively talented Bernd Rosemeyer and that old fox Hans Stuck.

Photo: Daimler Chrysler

Fagioli surprised everybody when he signed for the Zwickau team for 1937, which proved to be a year to forget. Tripoli was first on the menu and with Hermann Lang well in the lead, Fagioli, in an Auto Union this time, was mixing it again with Rudolf Caracciola and his Mercedes. The two were some way down the field in 5th and 6th places but, as usual, Fagioli was doing everything he could to pass Rudy. He succeeded a couple of laps from the end, but was seething because the German had bottled him up for so long that there was no time to press on and get himself up among the podium placings. Luigi was certain Caracciola had purposely balked him for most of the race and he was really going to do something about it this time. After the race, the Tough Guy picked up a heavy tire hammer, stalked over to the Mercedes pits and promptly threw the tool at Rudolf. It missed, so Fagioli got hold of a knife and was about to stick that into the Caracciola, when Alfred Neubauer and a mechanic dragged him away.

Years later the Italian said, “I had a fight with Caracciola, in fact I argued with him twice, once at Tripoli and once at Spa. I was convinced that he wouldn’t let me pass on purpose. I had a hammer in my hand and I went for him. Fortunately, they held me back and I am pleased I have nothing to regret. Now we are friends like before. In fact, more so.” Wishful thinking or fantasy at play: one of the two.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

The next race was Avus and Neubauer was a worried man. After the Tunis episode, he feared Fagioli would have another go at Caracciola and told the race organizers that if his number one and the Italian had to compete in the same heat, he would withdraw the entire Mercedes-Benz team. He got his way. The two never met in the final, either, because Caracciola won his heat, right enough, but Fagioli retired from his with mechanical problems. It was an unhappy year for Fagioli at Auto Union: his chronic rheumatism was extremely painful, so he only competed in 3 out of a possible 16 races, coming 5th in Tripoli, 4th in the Coppa Acerbo and 7th with Nuvolari’s help in the Grand Prix of Switzerland. When he turned up for the Swiss GP, he was limping badly and had to walk with the help of a stick—Luigi was having a miserable race as a back marker, when he was called into the pits and told to hand his car over to Nuvolari. But that was not the end. The world had not heard the last of Fagioli!

Once the second World War was over, Fagioli took his time getting back into racing and, after a couple of nondescript outings in 1947 and 1948, he drove for the Maserati brothers’ OSCA team in 1949, campaigning their little MT4 and scoring a respectable 2nd at the Circuit of Calabria. OSCA entered the car for him in the 1950 Mille Miglia, not really knowing what to expect: what they got was a mind-blowing 7th overall and an 1,100-cc class win from the Tough Guy, who was dogged by rheumatism but glad to be back in fighting form. Many believe driving that little car into 7th place, ahead of the likes of four-time Mille Miglia winner Clemente Biondetti in a Jaguar XK120, was a racing masterpiece—but even better was in store, and not only in the Mille Miglia.

Photo: vintagemotorphoto.com

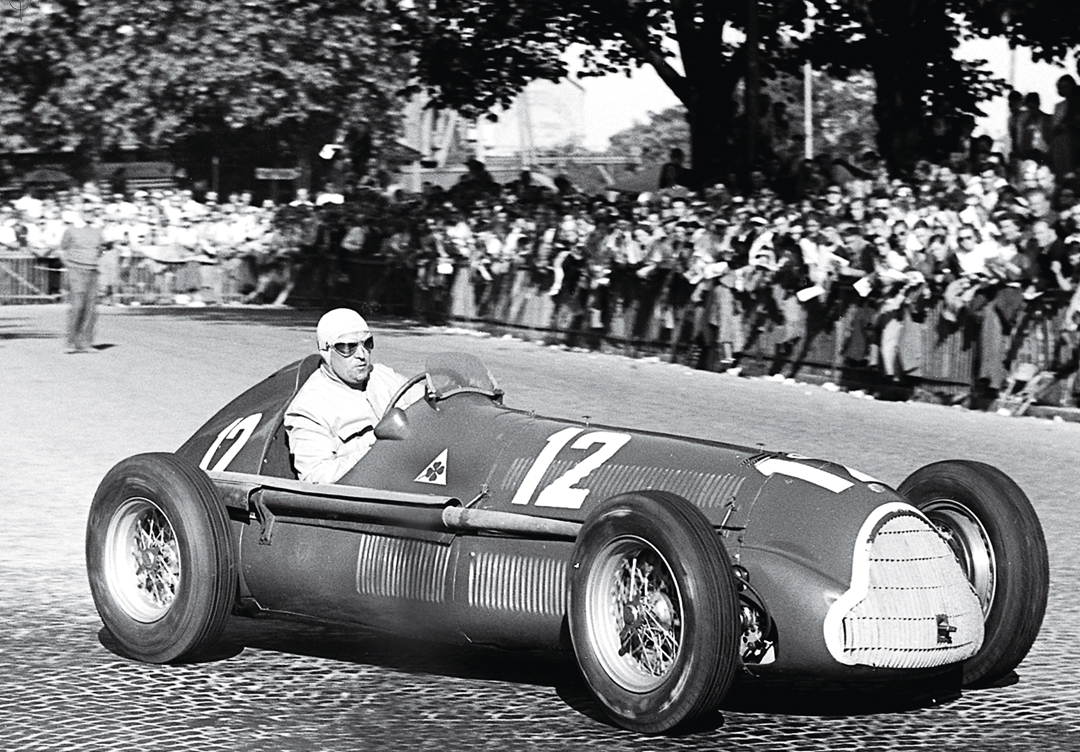

In 1950, at the age of 51, Luigi Fagioli signed for Alfa Romeo’s Formula One works team, where he would compete with Juan Manuel Fangio and Nino Farina. The trio became known as the three Fs and were to sweep everything before them that year: they won each one of the season’s Grands Prix. The Tough Guy did well and drove his Alfa 158 into four 2nd places (the Grands Prix of Great Britain, Switzerland, Belgium and France) and two 3rd places (the Pescara and Italian GPs) and came almost as close as Fangio to beating Farina to the first-ever Formula One World Drivers’ title—Farina won the championship with 30 points, Fangio was runner-up with 27 and the 52-year-old Fagioli came in 3rd with 24—rheumatism and all.

Fagioli may only have competed in one GP for Alfa in 1951, but he won it in a shared drive with Fangio. He did it again in the Mille Miglia that year, too: he brought his works OSCA home in 8th place overall and won his class.

Fagioli went back to the Brescia-Rome-Brescia marathon in 1952, but this time as a works Lancia driver at the wheel of the pretty Aurelia B20. That was the year Giovanni Bracco took the factory Mercedes-Benz cars to the cleaners and won the great race with the drive of his life, taking the occasional swig of red wine on the way: no less spectacular was Fagioli’s 3rd overall and 2,000-cc class win in the Aurelia. But Luigi was even happier about beating his old sparring partner, Rudolf Caracciola: in fact, he split the seemingly all-powerful Mercedes 300 SLs, finishing on the heels of 2nd-placed Karl Kling and ahead of Caracciola in 4th.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

At the end of May, Fagioli and his works Lancia were entered for the Monte Carlo Prize, a Grand Prix of Monaco touring car support race. Practicing on May 31, his B20 careened wildly out of the principality’s famous tunnel, smashed into a stone balustrade and threw Luigi out. He was rushed to the hospital with head injuries and a broken arm and leg, but died there three weeks later.

At 54 years and 11 days old, the Tough Guy’s turbulent life was over. He had been a hard man to get along with, especially if rubbed the wrong way, but he delivered the goods no matter what. Luigi Fagioli is still survived by his unbeaten record of 52 years standing as the oldest competitor to win a Formula One World Championship Grand Prix, plus a glittering array of motor racing achievements that includes 10 GP victories and a string of outstanding Mille Miglia drives. While delivering those results, he beat Tazio Nuvolari and Rudolf Caracciola, two of the 20th century’s greatest motor racing icons, more than once. And he turned in a drive for OSCA in the 1950 Mille Miglia that outshone even the most stunning performance by Clemente Biondetti, the only man to win the famed road race four times. Few others, if any, can lay claim to such accomplishments.

Photo: ACM