1949 Gordini 23S

Anyone who has ever listened to Peter Ustinov’s fabulous motor racing spoof of the 1950s, “The Grand Prix of Gibraltar” already is familiar with Amédée Gordini. Ustinov’s parody of the Franco-Italian, Monsieur Orgini, and “eez funny leetle blue Orgini cars” was not only hysterical but drew strongly on Ustinov’s knowledge of the then GP scene. The Orgini team was penniless, inclined to give up in existential despair and sit around smoking Gauloise, even while fueling the cars. Because they had no money for oil, they used a gift of sponsor’s cognac in the car instead! They couldn’t compete with the Teutonic efficiency of Herr Altbauer’s Schnorcedes team, or the drivers like Girling Foss and Bill Dill in the American Wildfowl.

While Ustinov’s portrayal of the French racing car constructor captured the frenetic way the team operated with very limited funding, it perhaps left a generation thinking that the real Gordini was not a serious player in the motor racing world, and that would be entirely wrong. Not only was Gordini building and racing sports cars, but he was involved in voiturettes, F2, and even F1.

Amédée Gordini’s personal and engineering pedigree was perfect for what followed. Like Bugatti, his origins were Italian. He had been born in Bazzano, near Bologna in 1899. The cars passing through his hometown in the early years of the 20th century in the Giro d’Emilia sparked a determination to have a life involved with cars. At the age of only 10, he was apprenticed at an engineering shop in Bologna. In 1910, he moved to a low level entry job at a Fiat agency. His foreman noted his abilities and helped him along. That foreman was Eduardo Weber, whose carburetors would one day rule in motor racing. At the age of 14, Gordini moved to work at Isotta-Fraschini, working under yet another significant foreman, Alfieri Maserati. He returned to Isotta after being in the infantry in WWI, but soon built his own car based on a Bianchi engine. This led him to being invited to be the private mechanic to the wealthy Count Moschini who wanted to construct his own machine for breaking records. A 180-bhp Hispano-Suiza aero engine soon found its way into a Gordini-built S.C.A.T. chassis. A young motorcyclist who lived nearby in Mantua was asked to try it. It was, of course, Tazio Nuvolari.

Gordini’s success on this project brought him a degree of prosperity, enough to allow him a holiday in Paris. On the eve of his return home to Italy, he threw a party for his friends and a great deal of champagne was consumed. The bill was so big that Gordini had to cancel his return in order to work and pay the bill. He never made the return journey to Italy—something that has to be seen as fate!

Gordini went to work for the Hispano specialist Cattaneo, and later brought his half-brother Athos Querzola to Paris to work with him. He married in the early 1920s and in 1926 set up his own premises in Suresnes, near Paris. It was in fact a barn, which was converted to a workshop, and the focus was repair and tuning of mainly Fiats. Gordini’s own competition career began in a Fiat, winning the Mont Valerian hillclimb the first of three times. This success led him to prepare a Fiat 514 for the Paris-Nice rally, the continuation of his early job at age 11 with Fiat, and a connection that would persist for many decades. Gordini started “proper” racing in 1935 with the 9-horsepower Fiat Mille Miglia. This car had been developed from the Balilla and Gordini’s car had been assembled in France by Simca, another significant connection for Gordini. Gordini modified and developed virtually every part on this car, starting on the road to manufacturing his own parts for competition. He tested the car in an 8-hour event at Monthléry and then drove single-handed in the 24-Hour Bol d’Or and won his first race.

Further successes followed in France, Belgium, and North Africa, and he soon built more cars around Fiat Balilla parts. His continued success prompted the growing Simca company to contract Gordini to use Simca parts exclusively. Simca was about to launch the Cinq in 1936, a 500-cc equivalent of the Italian Topolino. Gordini developed a 568-cc modified version for Le Mans, but the race was cancelled in 1936. However, in 1937 a Simca-Gordini team had emerged and two “baby” Cinqs and two newer 1,000s ran at Le Mans, driven by Gordini, and his staff including half-brother Athos. Such was the success of the Gordini “magic touch” that every new Simca got the Gordini treatment, and by the end of the decade, the name Wizard, or Le Sorcier, had stuck. That was immortalized in 1939 when he produced a two-seater sports racer of 1,100-cc called…the Wizard. Gordini and Scaron won the Index of Performance at the last prewar Le Mans with the car. Gordini’s frenetic style had also been established by this time, with constant work taking place on several types and sizes of engines, categories of cars and types of competition events.

When the war came, Gordini’s workshop was destroyed by bombs along with many of his drawings and records, as well as the three 1935–1936 Balilla-based cars. The other cars and Gordini escaped.

Postwar Racing and the 23S

Photo: Peter Collins

When the war was over, the French were the first to return to motor racing. A race was rapidly arranged to take place in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris on September 9, 1945, and was called the Coupe Robert Benoist after the great French driver who had been shot by the Germans as an allied secret agent. The first race on that day was for the Benoist Cup and was run for 1,500-cc cars and was won by…Amédée Gordini. Gordini has the honor of winning the world’s very first postwar motor race.

The first postwar-built Gordini was the fruit of the solid Simca-Gordini relationship and a number of early wins in the prewar cars. Though Simca supported Gordini and supplied parts, the basics were still Fiat, i.e. the transverse leaf front suspension and the base 4-cylinder 1,100-cc engine. With Simca parts and Gordini’s “sorcery,” a simple tubular-frame single-seater appeared and after leading races and then blowing up, the car soon started winning. Shortly after Gordini was 2nd in the first postwar sports car Grand Prix, the single-seater was in Italy to fight the Fiat-based Cisitalia of Piero Dusio. Dusio operated along similar lines to Gordini.

Toward the end of 1946, Gordini opened new premises in the Boulevard Victor on the edge of Paris. Gordini’s son Aldo was working in the garage at this time and the staff was a very close-knit group. New single-seaters appeared for Jean-Pierre Wimille, Maurice Trintignant, and Prince Bira who all drove in voiturette races. In 1947, the Gordini appeared in a “real” Grand Prix at Albi where Raymond Sommer was 2nd to Louis Rosier’s Talbot. The 1,100-cc car started winning races for 2-liter machines and humbling even bigger cars as well. In 1947, Gordini was experimenting with 1,100-cc engines and 2-liter V-8s. When the 1,220-cc single-seater appeared, it was almost unbeatable. In 1948, the 1,220-cc unit was up-rated with a bore and stroke of 78 x 75 mm yielding 1,433-cc, and twin oil pump lubrication was introduced. Though Gordini himself had retired from racing by this time, the 1.5-liter car started winning long-distance races.

Photo: Peter Collins

The death of Wimille in South America in early 1949 was a major blow to Gordini, though it wasn’t long before one Juan Manuel Fangio was driving the French car. Gordini then split from Simca and in 1949, Gordini produced his first four sports cars as a fully independent constructor. These first Gordinis without a Simca connection were chassis 16GCS, 17GCS, 18GCS, and 19GCS. The latter is the car you see on these pages. The four cars were powered by Gordini’s own twin overhead camshaft 4-cylinder engine, which had a capacity of 1,491-cc. The model designation of these cars was the T15S, as it was a 1.5-liter sports car. Over the years, there has been much confusion over these cars, as the type numbers and chassis numbers were mixed up, and the basic car was seen, often within a very narrow time period, with several different engines. That is particularly true of 19GCS.

Chassis 19GCS

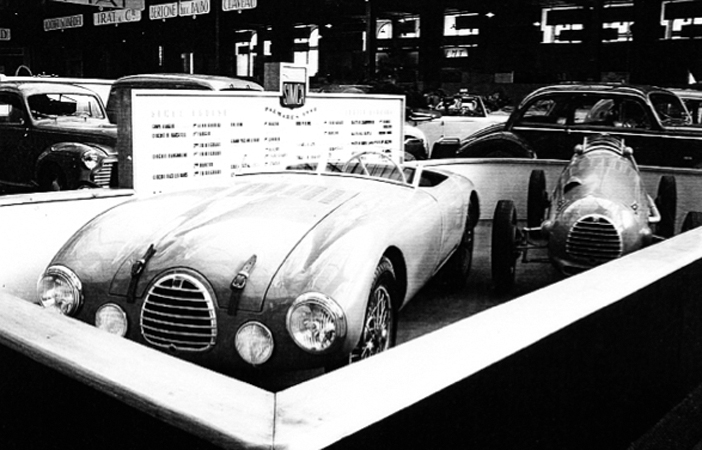

Chassis 19GCS made its first public appearance on the Gordini stand at the 1949 Paris Motor Show. It was originally intended that all the new cars would appear at the 1949 Le Mans race but single-seater events had taken priority. Maurice Trintignant and Robert Manzon drove 18GCS but retired, and 19GCS made a gentle entry at the Paris show with its 1.5 engine and a four-speed gearbox, while the light alloy body helped it to weigh in at only 650 kgs. The engine was known as the T15.

In spite of the easy start, 19GCS would have a reasonably hard—and long—life. It ran at Le Mans for the first time on June 25–26, 1950, with Andre Simon and Gordini’s son Aldo driving (car number 34), but it was forced to retire. The car was quick at Le Mans but the gearbox broke after six hours. It then was raced, still in 1.5-liter format, three times in July at the Mont Ventoux Hillclimb, the 12 Hours of Paris, and the Rouen Sports Car Grand Prix, driven by the various members of the Gordini team. At the end of August, it appeared in the rather obscure Coupe Rhineland. It must be remembered that there were an unusually large number of monoposto races going on in this period and the Gordini resources were stretched to the limit.

In early June, the car competed at the Bol d’Or endurance race at Montlhéry, in the run-up to the 1951 Le Mans 24 Hours. This time the drivers were two veterans, bike rider Georges Monneret, and Pierre Veyron who had won the race in 1939 driving one of the Bugatti “tanks.” Chassis 19GCS, running as number 37, was in very similar trim to how it ran the previous year, except for two small air intakes on the bonnet, which were occasioned by the introduction of Gordini’s own entirely new, double-overhead camshaft engine. The Gordinis were the quickest cars in the 1500-cc group, but didn’t finish. Chassis 19GCS made it through 14 hours before the engine gave up. In October that year, it had one more run, this time at the Coupe du Salon at Montlhéry.

The car then had its most sensational year in 1952. In March, it ran in 1.5-liter form at the Cote Lapize and Coupe de USA events. Then in 1952, Amédée Gordini developed a six-cylinder engine, which was essentially a larger brother of the four-cylinder. He built it primarily as a 2-liter for F2 races to which Grand Prix racing would be run in 1952 and 1953. He also built the engine in 2.3-liter capacity and three of the four original cars, 16GCS, 18GCS, and 19GCS were built with the 2.3-liter engine. These cars also featured modified and sturdier running gear (brakes, rear axle, etc.) and also conversion to right-hand drive. This final change being another factor to confuse historians—seeing very similar cars with steering on both sides!

The first of the 23S cars to race was 16GCS, which Robert Manzon drove in the sports car race, which replaced the standard Grand Prix at Monaco in 1952. Manzon was one of several drivers involved in the famous multiple car crash that year. Manzon looked like a very possible winner but sadly the chassis was written off in the incident.

Gordini had entered a 1.5-liter car at the 1952 Le Mans race, as well as the 23S. The 23S was chassis 19GCS with the 2.3-liter engine (known as a Type 22) for Jean Behra and Robert Manzon, two formidable French pilots. Famed British politician, writer, and car enthusiast Alan Clark was also Road and Track’s correspondent in the early ’50s and he remembered Le Mans for Behra and Manzon going quicker than anyone else. Other journalists at the 1952 Le Mans race were also captivated by the Gordini, noting that it was managing 234 miles or 28 laps between refueling stops in practice, but that Gordini himself was late for scrutineering and incurred a fine. At this point the wings on the 1.5-liter car were extended slightly and the rear number light was moved. In the race, 19GCS had secured the lead after two and half-hours—overall and on Index—which was a mighty achievement. By this time the average was 93 mph and by midnight it had been raised to 101 mph. At 3:00 a.m., it came into the pits after leading for eight and a half hours. An electric problem was worked on but at 3:35 it was in again for fuel. It had been leading the works Ferrari 225S and 340 America, the Jaguar C-Types, Allards, Cunningham, Talbot, and Aston Martin.

Gordini noticed metallic fragments and dust on the driver’s overalls…the front brakes were breaking up. Both Behra and Manzon argued hard to continue without front brakes but Gordini wouldn’t hear of it. At 4:00 the car was retired and at that stage the average speed was still 93 mph. Charles Faroux in his report was so impressed he said that Gordini had the gift and intuition of a genius. It had been clear that 19GCS was the fastest sports car in the world, at that time.

One week later, the Belgian Grand Prix was to be held at Spa. The organizers were very anxious to get another Belgian into the race and Gordini was approached. In spite of its endurance run at Le Mans the week before, 19GCS had the 2.3 engine removed, and effectively the car became a Type 16 (the 16 indicated a monoposto) with the regulation 2-liter Type 20 unit fitted. The car was entered in “streamliner” form with a metal tonneau cover in place over the passenger seat, which had been removed and the lighting aperatures had metal covers added. Belgian bandleader Johnny Claes took the wheel. The aerodynamics in the wet race were not such a great advantage, but Claes was a competent driver and took the car to a very impressive 8th place. This made 19GCS the only Gordini sports car ever to race in a Grand Prix. Furthermore, it became the only car ever to lead Le Mans and then appear in a Grand Prix…all within the space of eight days!

If that were not enough, the car went back to Paris, and seven days later…yes, seven…it had the 2.3 engine back in and was dispatched to Reims for Robert Manzon to drive in the Reims 12 Hours. To show how quick the car was, Manzon qualified on pole by five seconds from Stirling Moss in the C-Type Jaguar and Pagnibon’s Ferrari. The weather was so hot that it was necessary to remove the two headlights and the grill to allow more air into the engine. This seemed to work and Manzon pulled away to a 17-second lead from Moss after only 10 laps. On the 17th lap, however, 19GCS suffered a stub-axle failure and crashed, hitting an electricity pylon. Manzon escaped from the high-speed accident, but Reims suffered an electrical blackout for four hours. Was it Gordini’s “darkest hour”?

The car remained with Gordini for many years, until collector Serge Pozzoli bought it in 1972. It remained at his Le Gerier museum until 1986 when it was sold to Robert Tessier. Tessier had it fitted with a single-seater body. The Pozzoli family, including grandson Flavien Marcais, bought it back into the family where it remained until purchased by Irish architect and vintage racer, the affable Eddie McGuire in 2002. It was restored over time by Spencer Longland and Aubrey Finburgh back to the condition it was in when last raced in 1952. In 2004, McGuire brought it to Monaco and subsequently Le Mans…where it truly belonged.

Driving 19GCS

I test drove the Gordini at Silverstone on the same day as I had driven the F2 Ferrari 500 [VRJ, Oct. 2005], both cars having been driven by some of the most charismatic drivers ever to get behind the wheel of a racing car. Both cars had Trintignant connections, but the Gordini had led Le Mans with Jean Behra in this very seat…how does one get one’s head around that?!

Back in October 1952, Autosport’s Sir James Scott-Douglas managed to convince Gordini to let him test a 23S at Montlhéry. He believed it to be the Le Mans car but that is inaccurate because the car had not yet been repaired. The car he was to test was about to be sent off for the Carrera Panamericana and that was definitely not 19GCS. What he did get right, however, was the feeling of elation, anticipation, and surprise that came as a result of getting behind the wheel of a quite small car, which would run at quite large speeds!

At Silverstone, I rather wished I was at Montlhéry because the car was using Le Mans gearing, with a high first gear that made getting off the line a delicate business. Better to give it some revs and drop the clutch and get it going than play around and stall it. With weight around 670 kilos, the acceleration is stunning, and one realizes immediately why the Gordini was such a giant-killer, or would have been if it had been more reliable. Eddie McGuire’s performances recently, especially at Monaco and Goodwood, show that the reliability is certainly there for sprint races. Braking is firm and certain, the Girling-derived Gordini drums working smoothly at all times. They are hydraulically operated with two leading shoes.

Photo: McGuire Collection

The twin-ohc engine goes to the limit pretty quickly, providing great acceleration through the gears. The power range is impressive from 2,800-3,000 rpm onward on up to the 6,000 rpm limit, where the engine is producing a good 180 bhp. The starting procedure itself took some thinking through, with the fuel pump needing to be on along with a starter lever, while the starter button is engaged. Once the six-cylinders are awakened, it is easy to believe you are in charge of a much bigger car. You need to be in charge, too, because once you are accelerating away, that is not the time to learn what to do next. I think I was getting to 60 mph in 1st gear with these ratios and suddenly finding myself in corners before I was quite ready. But once underway, the performance is just so amazing for such a small engine. With synchro on all four gears, going up and down the box is a dream, making the car not only fast but a great deal of fun to drive. On the wide-open spaces of Silverstone, we were able to indulge in some heavy brake testing and real exploration of the Gordini gearbox.

Chassis 19GCS, of course, has the aero screen on the right side where the steering is after the pre-Le Mans conversion. I was able to get under the bonnet to have a look at how Gordini’s design seemed to have allowed the possibility of such a conversion should it be needed. How he had the time to think such things out is hard to imagine. There is an external mirror on the driver’s side and a center mirror over the dash. There is a single leather bucket seat with seat belts. The driver is well aware of the metal tonneau cover adjacent to the left ear. As you drive, you are also aware of just how sleek this car is. It feels it from the inside and looks it from the outside, with the delicate tapered tail which adapts a variety of angles according to how hard the corner is taken. The period intakes on the bonnet signal the only modification of the body from 1951 to 1952.

Development work has gone on to improve the handling, and Eddie McGuire showed how well he could get the car around the twists and turns of Monaco. The car flies out of slower and medium speed corners with little fuss, and is easy to steer through corners on the throttle. I managed to oil the plugs up a bit as we slowed down to get some photos at low speed but that was cured by putting the throttle down and sailing away. I could watch the rev-counter needle rise toward the limit, but carefully kept it to 5,500–6,000 at most. There are only a few gauges to watch on the simple dash and a few buttons and switches to master. Gordini was, after all, a minimalist, and everything went into function and lightness, and experts argue he was the inspiration for Colin Chapman’s approach.

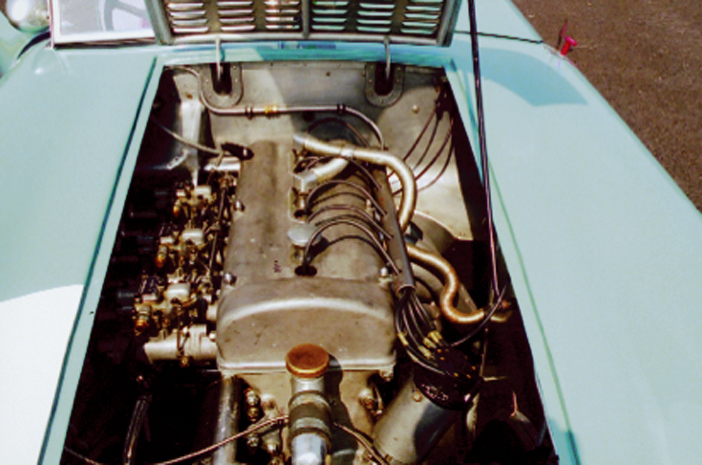

The 23S was sitting on 5.50-15 tires all around with lovely 4.5″-width wire wheels, and under the bonnet reposed the potent Gordini 2.3 lump, fitted with the handiwork of Gordini’s one-time foreman, Weber, triple 40DCO3s. A ScintillaVertex magneto runs off the left front side of the engine (number GM35). The tubular chassis is also light in weight and the body and body supports are all built to save weight. The car bristles with advanced, for the time, technology: dry-sump engine, effective aerodynamics, well-developed brakes. In fact, 19GCS originally encompassed all the features you would want to build into a historic car if you were modernizing it today. That was “wizardry.

Historic racer Willie Green tested the car after it had been restored: “It’s one of the most stunningly underrated cars I have ever driven from the 1950s that will blow everything into the weeds at Monaco I am sure. It’s really a great car.”

Buying and running a Gordini Sports Car

The well-known racing Gordinis are pretty much accounted for, but fortunately a good number of the small amount made have been preserved, though they rarely come up for sale. The provenance of 19GCS puts a price tag of close to a million and a half dollars on it, should it come onto the market. Its Le Mans record alone is fascinating if not victorious, but the fact that it led Le Mans, ran in a Grand Prix, and then led the Reims 12 Hours all on consecutive weekends is totally unique. Add to that, it is a very competitive racing car today with the attractive guaranteed entry anywhere.

The Gordini, like all specialist-built sports and single-seaters, needs a degree of expertise in understanding what the “sorcerer” was putting together under the skin. While the design is straight-forward, and it is an easy car to work on, it is a highly specialized piece of engineering. Fortunately, there are an abundance of historic racing experts who can look after the 50-plus-year-old Gordinis, Ferraris, etc. that we see on the circuits today.

Specifications

Chassis: Tubular frame

Body: Aluminum

Wheelbase: 2,240 mm

Track Front: 1,140 mm; Rear: 1,160 mm

Weight: 670 kilograms

Suspension: Front: Wishbones, coil springs, telescopic shock absorbers. Rear: Solid axle, torsion bars, telescopic shock absorbers

Engine: Gordini straight 6-cylinder DOHC/2 valves per cylinder

Capacity: 2,262-cc

Carburetion: Triple Weber 40 DCO3

Bore and stroke: 80 x 75 mm

Power: 180 bhp @ 6,000 rpm

Gearbox: Manual 4-speed and reverse

Brakes: Gordini drum brakes

Tires: 550/15

Top speed: 145 mph

Resources

Grateful thanks to Eddie McGuire for allowing us to drive 19GCS and for access to his records.

Scott-Douglas, J. “The 2.3-Litre Gordini,” Autosport, October 31, 1952.

Sheldon and Rabagliati, History of Grand Prix and Voiturette Racing. Vol. 4, 1992.