I would rather be remembered as somebody who did some work against cancer than the driver who won the Belgian Grand Prix,” said Gunnar Axel Arvid Nilsson. Nevertheless, he should also be remembered—in the words of Nick Jordan, mechanic to Gunnar’s rival Tony Brise in Formula Atlantic—as “one of the best to come out of Sweden.”

Gunnar was born on November 20, 1948, to Arvid and Elisabeth Nilsson in Helsingborg, “the pearl on the Oresund coast.” The infant Gunnar, fascinated by cars, hummed engine noises as he clung to Elisabeth’s vacuum cleaner. Arvid encouraged this interest by allowing him to sit on his lap and steer the family car. By age 12, Gunnar was driving the car in and out of the garage and would throw tantrums if prohibited. He acquired a moped at 15 and “terrorized” elderly ladies with his wild driving. When watching the Monaco Grand Prix on television, he announced to his parents: “One day, I’ll drive a racing car down there.”

In 1964, Arvid died. Elisabeth did not approve of Gunnar’s ambitions and, later on, she offered him a motorboat to stop him from racing. She wanted him to devote his time to Arvid’s construction company instead. Nevertheless, he was undeterred and raced a homemade go-kart at a local track. One day, the machine was smashed to smithereens as he crashed into a heap. At a disco in Helsingborg, he became friends with Fredrik Af Petersens, former Mini and Formula Vee-driver-turned-reporter. “We started talking and found out that we enjoyed motor racing and he wanted to go racing,” he recalled. “Like it is when you meet someone, you either hit it off or you don’t; and we hit it off immediately.” Gunnar bought a Formula Vee car from Dan Molin and raced it in 1972.

At the start, his driving style lacked discipline, but as Petersens stated: “He studied a few of the other guys who had been racing for a few years and had a chat with them, and found his own way. He was definitely a gifted driver who understood that, after a few races, you can’t just go quickly. You have to drive with the inside of your brain.” Petersens acted as Gunnar’s gofer, which involved “Organizing tickets, driving his caravan to circuits, and going to the Pederzani brothers to pick up F3 engines later on. Everything you can imagine, except driving the car.”

Jo Bonnier, impressed by the fact that the young man had gotten a 2nd place at Zeltweg, signed him for his Super Vee team for 1973. Bonnier never lived to see the promise fulfilled, as he was killed at Le Mans in 1972, but had already asked Kottulinsky to look after Gunnar. Alongside the veteran Kottulinsky in the Lola T252, Gunnar participated in the Volkswagen Gold Cup and the Castrol GTX Trophy, and finished 5th in both championships. “Gunnar was a coming man. I knew he would get to be a big boy,” Kottulinsky remembered. In his debut at the Norisring in a GRD-Ford entered by Pierre Roberts, Gunnar finished 4th on aggregate time. “He had no problems adapting whatsoever to stronger cars, no way,” said Petersens.

The year 1974 was Gunnar’s “breaking point” in Petersens’ words, when he attracted considerable attention. It was when he bought a March fitted with a Toyota-Novamotor engine from former Lotus- and BRM-driver Reine Wisell’s team. He competed in the German Polifac and Swedish F3 championships. In Polifac, Gunnar achieved two 2nd places and a 4th and, in the Swedish series, he was 2nd twice and set his first pole and fastest lap.

In Formula 2, at Karlskroga, he retired after colliding with David Purley but at Hockenheim in a year-old March BMW entered by Brian Lewis, he excelled again. In the first heat, a throttle wire broke after 15 laps so he started last in the second. Yet, he drove through the field to finish 4th. That was good enough for the March works team for 1975. Robin Herd of March disagreed with the “Wild Swede” epithet he had been given by the press: “Gunnar was a careful driver and, contrary to what people said, he was a very capable driver who wasn’t one for smashing up cars.” Despite crashes at Cadwell Park and Monza, Gunnar stayed out of trouble.

Gunnar made just one appearance in Swedish F3 with a victory at Knutstorp, as he focused his efforts on Britain. He won six rounds in the BP Super Visco championship, setting fastest lap seven times and starting on pole five times. He was champion with 74 points to teammate Alex Ribeiro’s 59. Herd vividly remembered the British Grand Prix support race where, in front of the F1 team owners, Gunnar and Ribeiro fought for the lead: “They went into the last lap nose to tail and I remember turning to Max (Mosley) and saying, ‘Only one of them is gonna come round next time and guess who it’s gonna be!’ Sure enough, it was Gunnar.”

In addition, Herd praised Gunnar’s abilities off the circuit, likening him to Emerson Fittipaldi: “They were both mischievous, and Gunnar was mischievous in the extreme. Gunnar was very good politically and I don’t mean politically in spin or in that sense at all. I felt that when he was driving for us, if I opened a door, I felt there were ten Gunnar Nilssons! He really did, great credit to him, work at his career on a personal level and making sure that he was always at the right place at the right time.”

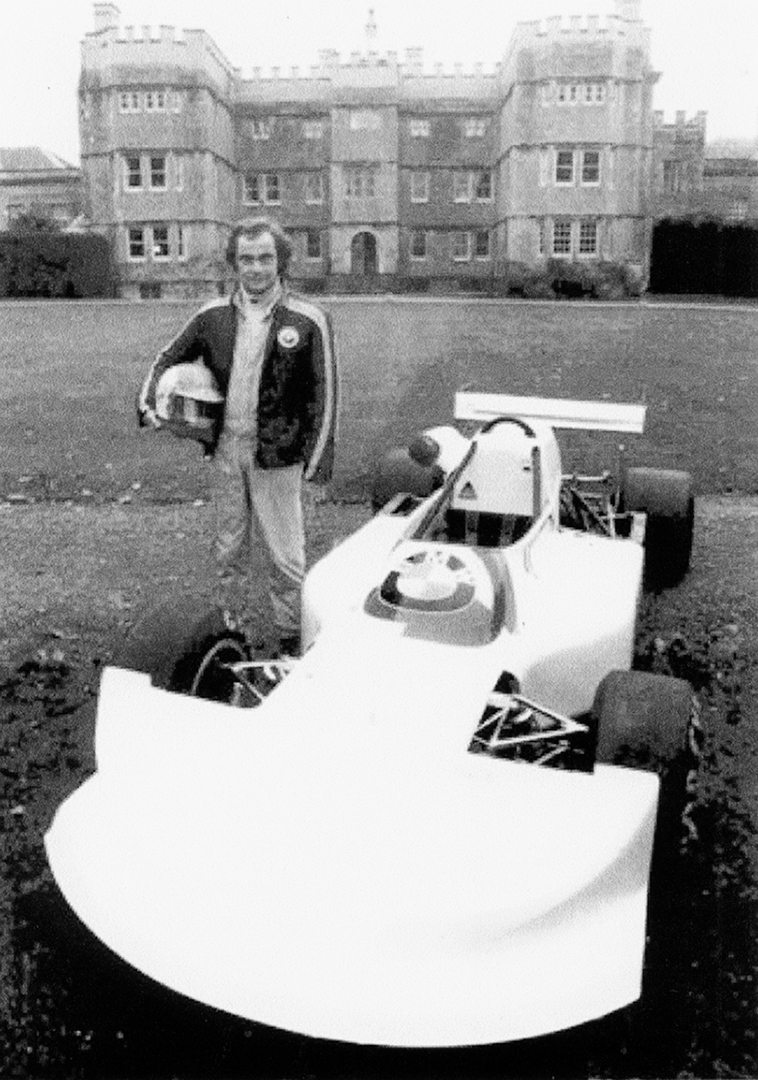

Gunnar drove a Chevron B29 for Ted Moore’s Rapid Movements team in Formula Atlantic. He helped his career advance by winning four races, making a big splash. He was then invited to test a Williams FW03 at Goodwood. Completing 154 laps, he lapped 0.5 seconds faster than Vittorio Brambilla’s lap record. He also sampled a Brabham BT44B at Silverstone. Williams offered a drive for 1976; Lotus and McLaren also expressed interest. But Gunnar was persuaded to remain with March since it offered him a full F2 season and a few F1 outings, whereas McLaren only offered a third car for a few races.

As it turned out, it would ultimately be Lotus instead. The team was in the doldrums following a poor 1975 season with the obsolete Lotus 72. The Lotus 77, in the words of mechanic Glenn Waters, was also a “dire car,” and an unhappy Ronnie Peterson would leave after Brazil. Gunnar replaced him and had a tough start, qualifying last and retiring early at Kyalami. At Long Beach during qualifying, he slammed into the wall at Shoreline Drive at high speed, leaving him with a strained neck for months. Matters improved drastically at the following race at Jarama where he finished 3rd. Ken Tyrrell became a fan, remarking that it was the performance of a future world champion.

The Swedish press, already pleased that there were two Swedes in the sport, devoted more coverage to Gunnar: “Ronnie was shy and didn’t trust many of the Swedish journalists because he thought they only wrote about death, about money and the danger,” explained Petersens. “Gunnar, on the other hand, was the contrary. He was open; he was happy and was laughing. He always talked a lot which was perfect for the Swedish journalists to talk to Gunnar.”

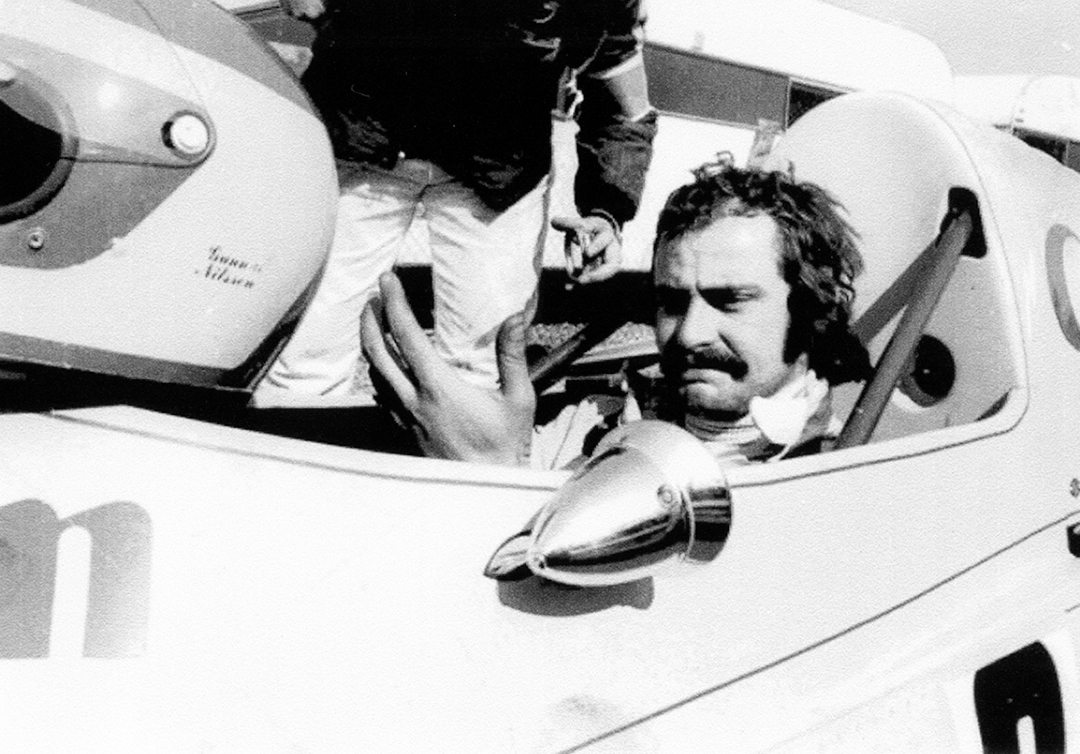

Photo: Gunnar Nilsson Institute

The atmosphere in the team around Gunnar was good, compared to Peterson’s acrimonious split. “He was a good solid member of the race team. Valued by everybody, loved by everybody. Good guy, good bloke,” Waters fondly remembered. He spent two weeks in Sweden with Gunnar after his victory in Belgium. “He looked after us really well there. He made sure we were really comfortable in the hotel and popped in to see us a couple of times. Really good fun.”

Glenn spoke of the camaraderie between Gunnar and the mechanics: “I spent a long time in racing, particularly with lots of young drivers, and what really makes a difference to where somebody will go with their racing career is their ability to get people to want to help them. Some people build really big barriers around them; you can’t help them for all you want. Others are easy to help, and Gunnar was one of those. He was one of the people that you really wanted to help and assist and see him go forward. He was a good guy. He was one of the people that if there was some problem with the car or he’d damaged the car or whatever else, he’d get out and he’d want to become involved. He was one of the people that enjoyed being with the mechanics in the team. He had some empathy with them; he would share jokes and buy beers and whatever else.”

Andretti was also close to Gunnar. “It was very easy to befriend Gunnar,” he said. “He was one of those chaps that had a lot of charisma and I thoroughly enjoyed being with him. Off the track, we used to spend considerable time doing things together. We never had a word sideways. In Pennsylvania, at what I call my lake resort, with all the toys, we used to play so hard and play tennis and do all the watersports and just really enjoy ourselves. It was a great relationship and a special time of my life.”

Mario was a good teacher to Gunnar: “We were at Fuji and I had an engine problem, so I stopped alongside the circuit and I was watching him negotiate a couple of S corners and he was way overdriving the car. You could tell he did not have the feel of the throttle to apply power, he was doing a lot of wheel-spinning. When I went back, I told him, ‘Gee, you’ll pick up so much time if you’ll just cool it a little and make sure you connect with the track. Don’t just make noise.’ He thanked me for that.” Compared to Peterson: “Gunnar was a more technical driver when he applied himself. He was always very interested in trying to make the car do some of the work for him.” Gunnar used this advice well, outqualifying Andretti at Jarama, the Osterreichring and Monza in 1976. Andretti continued: “I thought he was always there; Gunnar was always one to be taken seriously, that’s for sure.”

Gunnar helped himself to be taken seriously by finishing 10th in the championship standings with 11 points. Armed with the Lotus 78 wing car, he underlined his seriousness even further in 1977, especially on June 5, at Zolder. He avoided the first-lap collision between Andretti and John Watson and, after 21 laps, he came into the pits for dry tires. He was in for more than a minute due to a cross-threading wheel nut. Rejoining in 8th, he scythed his way past Peterson, Depailler, Brambilla, Jones and Hunt. The wing car thrived in damp conditions. When Scheckter pitted, only Lauda remained. He lost 7 seconds when he spun, but he caught Lauda again on the 50th lap and led to the end. He was so overjoyed that he shouted: “I won! I won!” when he passed the checkered flag.

Other outstanding performances included Jarama, where an anxious Gunnar talked until 4:00 a.m. to Petersens in his hotel room. He had qualified 12th, compared to Andretti’s pole. He drove a hard race and finished 5th, the last car on the same lap as the victorious Mario. At the Osterreichring, starting from 16th, he rose to 2nd behind Andretti after remaining on wet tires. After falling to 13th when he pitted for dry tires, he rose to 3rd before his engine failed. At Fuji, Gunnar started 14th when Mario was on pole again. The red-liveried Imperial Tobacco car rose to 4th before retiring after 64 laps. “He never gave up,” said Petersens.

He earned 6th in the Top Ten drivers of the Autocourse annual of 1977/78. Mike Kettlewell described Gunnar as one of the most improved drivers of the year but added: “The amusing Swede still has a long way to go in Formula One.”

That was correct, regarding toughness. After a frosty beginning, Gunnar and Colin Chapman became good friends. It was, in Waters’ words: “A really good relationship, a good employer-employee relationship.” Like Andretti, Chapman was a good teacher. At Jarama, Chapman advised Gunnar: “Just keep cool and everything will be okay.” Gunnar benefited as shown. There was one low point at Hockenheim as Andretti recalled: “I know that Colin was bollocking him like he was a five-year-old child. He made a comment to me, ‘Sorry you had to see that ugly side of me.’ I said, ‘You know something Colin? That was really, really ugly and if I was Gunnar, I would’ve walked away.’”

It was something Chapman dished out to his employees when they did something crass or stupid, but Mario was astonished by Gunnar’s acceptance of that outburst. “I would’ve never taken that. One of Gunnar’s faults was that he was too damn nice,” he said. “That was in his character; he just didn’t want to make waves.”

Petersens agreed: “Perhaps Gunnar didn’t have that last bit of killer instinct because he wanted to be friends with everybody and just have a good race.” F1 in the 1970s had ‘really nice guys,’ so it would not have set Gunnar back that much as it did Elio de Angelis, who was also described as a ‘nice fellow.’ In short, Gunnar had to learn to be more ruthless and to be an ‘egoist.’”

Kettlewell also wrote: “It is to be hoped that Gunnar will be furnished with a competitive car so that he can once more display his race-winning form as he did at Zolder.” With the “favored Lotus son” Peterson returning to Lotus with welcome money from Count Guggi Zanon, Gunnar would be leaving. The Swedish papers were on tenterhooks to hear where he would be driving for 1978. He tested for McLaren, but it would turn out to be the breakaway Arrows team. He hoped to be team leader there, “to fly with my own wings,” as he said.

It was against Petersens’s advice, when Gunnar told him the news while dining at Watkins Glen. “I wasn’t too sure about the whole situation. But Gunnar wanted to have a change, and be part of a whole new team and be able to build it up together with the others,” mused Frederik.

That desire was greatly helped by the friendship he formed with his intended boss, Jackie Oliver. “I used to spend a lot of time with him at his home in Sweden and we were soul-mates in that regard,” Oliver said. “His personality would have fitted in very well with the new team because he was a pleasant individual that I got on very well with.” In Helsingborg, Oliver experienced the nightlife with Gunnar. “We had a lot of fun. I always remember doing that during the summer and it always amazed me that we’d come out of the nightclub at 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning and it was still daylight!” He laughed.

Although he was doing it for fun, Gunnar proved his mettle in “tin-top” racing as well. In 1976, he drove the BMW CSL in World Sportscar Championship rounds. He retired at Silverstone after 42 laps but won with Dieter Quester at the Osterreichring. In European Touring Cars, with the BMW ‘Batmobile,’ he won the Nüürburgring Six Hours by two laps and, at the Tourist Trophy at Silverstone, he finished 4th due to a faulty pump and puncture after having led. In 1977, he competed in the International Race of Champions (IROC), in the U.S. Despite having never raced on ovals before, driving a Chevrolet Camaro Z28, he finished 5th at Michigan. At Riverside, he finished 6th twice, after a duel with Richard Petty. He was so exhausted that he needed to be lifted out of the car and showered with his overalls on! He earned $7,500 in prize money and qualified for the Daytona 500 for the following February. Having been barred by Chapman before on the grounds of safety, he hoped to take up the invitation for the Indianapolis 500.

However, those hopes would be dashed. Gunnar was suffering throughout 1977, and Waters powerfully illustrated how the illness manifested itself. The Hewland gearbox had a 5-inch diameter steel input shaft that served as a feeder mechanism for the selector rods. The shaft could not be bent, even if it had been put into a vice and hit with a 2-pound hammer all day. Only the driver provided the load, and Gunnar broke the shaft at the warm-up at Long Beach. He’d never done that before and Waters was bemused: “We were thinking, how the bloody hell do you do that?”

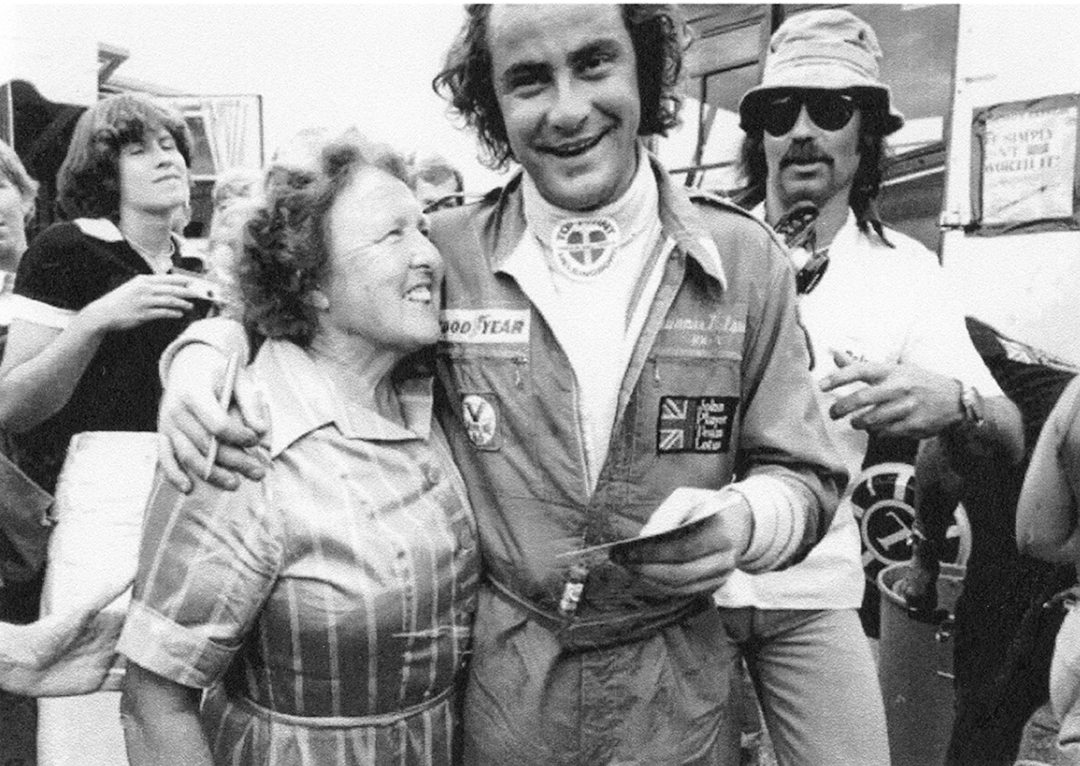

Photo: Gunnar Nilsson Institute

At Fuji, gear-selection problems halted Gunnar. “He had failed the gear-selection shaft, the rod that runs alongside the engine,” said Glenn. “What he had done was that he’d bent this 5/8-inch diameter rod from being a straight piece of rod; he’d bent it compressedly by applying a load to the end. It was a compression failure that had bent it. I think that was some manifestation of his illness. I sat on the airplane talking to him on the way back, and he was telling me personally that he was having all sorts of difficulties.” Gunnar refused to sit out a few races and see a doctor. “That was Gunnar’s way. ‘I have a job to do and I’ll finish it. The pain I have, I can live with that,’” said Petersens. After Fuji, Gunnar visited a doctor who was a friend of Ken Tyrrell. Cancer was diagnosed and he was sent to London for treatment.

He would never be well enough to drive the Arrows FA1. In the hands of Patrese, it set 5th fastest lap on its debut at Jacarapagua; led at Kyalami for 36 laps before retiring and finished 2nd at Anderstorp. With Gunnar at the wheel, Arrows would have had “fantastic results,” in Oliver’s words, due to his experience and being a more “moulded personality” than Patrese, who had under his belt F2 and nine races with Shadow. While conceding that Gunnar would have been affected, as the team was by the legal wrangling that led to the banning of the FA1, there was “no doubt. Absolutely no doubt” that Gunnar would have won a race for Arrows, a moment the team would never enjoy.

Gunnar’s illness was kept secret until he appeared at Brands Hatch for the British Grand Prix, visiting the pits with his flowing mane of hair gone, due to the treatment. It was “psychologically the best medicine I could get,” he said. “He wouldn’t let on. He was very positive about his condition, but it went downhill, poor guy,” said Andretti.

The sight of children suffering while at Charing Cross appalled Gunnar. “He thought it was so unfair that all the children at the hospital, afflicted by cancer, despite being so young, had their days numbered,” said his lawyer, Kjell Strenstrom. “He had experienced so much in his life that these small children never would have a chance to do.” That motivated him to do something. His will and testament originally left his estate to promote future racing talent. When the doctors told him there was little they could do for him anymore, he changed it for cancer research.

The relationship between Gunnar and Arrows used its PR agency run by Barry Gill, to help Gunnar’s campaign. Oliver remembered: “I was in and out of the hospital the whole time with Gunnar saying, ‘Come on, I’m going to beat this battle. I’m going to raise money to help the hospital and, when it’s all over, I’m going to drive your car.’”

Sacrificing his comfort by refusing painkillers to ensure he was of sound mind, he established two organizations: The Gunnar Nilsson Cancer Research Trust Fund and The Cancer Treatment Campaign. His mother spent her entire fortune to continue Gunnar’s initiative in Sweden before her death in 1992.

Gunnar’s personal battle was lost on October 20, 1978. A reverberating sigh from Waters: “That whole time, the death of Ronnie at Monza and Gunnar dying, was, let me tell you, a pretty unpalatable time.” In the fight against cancer and saving the lives of others, Gunnar made a tremendous difference as Oliver concluded: “We launched a campaign to raise £350,000 for a linear accelerator. At the end, we raised £3.5 million for a whole wing on the Charing Cross Hospital, which is still called the Gunnar Nilsson Suite where we have a cancer treatment center at that location. He did leave behind a legacy to the disease that killed him.”