Just prior to 1930, Pocantico Hills, New York, was the country home of Barron Collier, a wildly successful businessman who made his fortune initially in advertising on streetcars. While, also the largest land owner and developer in the state of Florida, his country property became the launching pad of ARCA, the Automobile Racing Club of America.

The wealth of their father allowed teenaged sons Barron Jr., Sam and Miles to create racing circuits on the estate’s many driveways and service roads. They gave their organization the name OARC: Overlook Automobile Racing Club. These early races found the brothers and their friends racing motorized buckboards and homemade machines with low-powered cycle engines. Even in these humble beginnings, the brothers imitated the Grand Prix and sports car races of Europe as best they could. They continued for several years, even going so far as to have their own point standings.

By 1933, the brothers and their friends had graduated to full-size cars like MGs, Austins, Bugattis and Willys. They also graduated to a new name: ARCA, the Automobile Racing Club of America, even though all the members at the time were local to the area. As time went on, more and more friends joined in; people from as far away as Boston and Philadelphia came to watch, as well as participate.

Before the beginning of 1934, it was apparent that the driveways and service roads of Overlook could no longer contain ARCA’s events. So a new course was devised, the “Sleepy Hollow Ring,” using other land owned by Father Collier.

In June of 1934, ARCA became a corporation, thus giving the club an enhanced image. Bill Mitchell, at the time an illustrator for Barron Sr. (and later to become a member of the design team that created the C2 Corvette) designed the ARCA logo, featuring a head-on view of an Auburn Speedster.

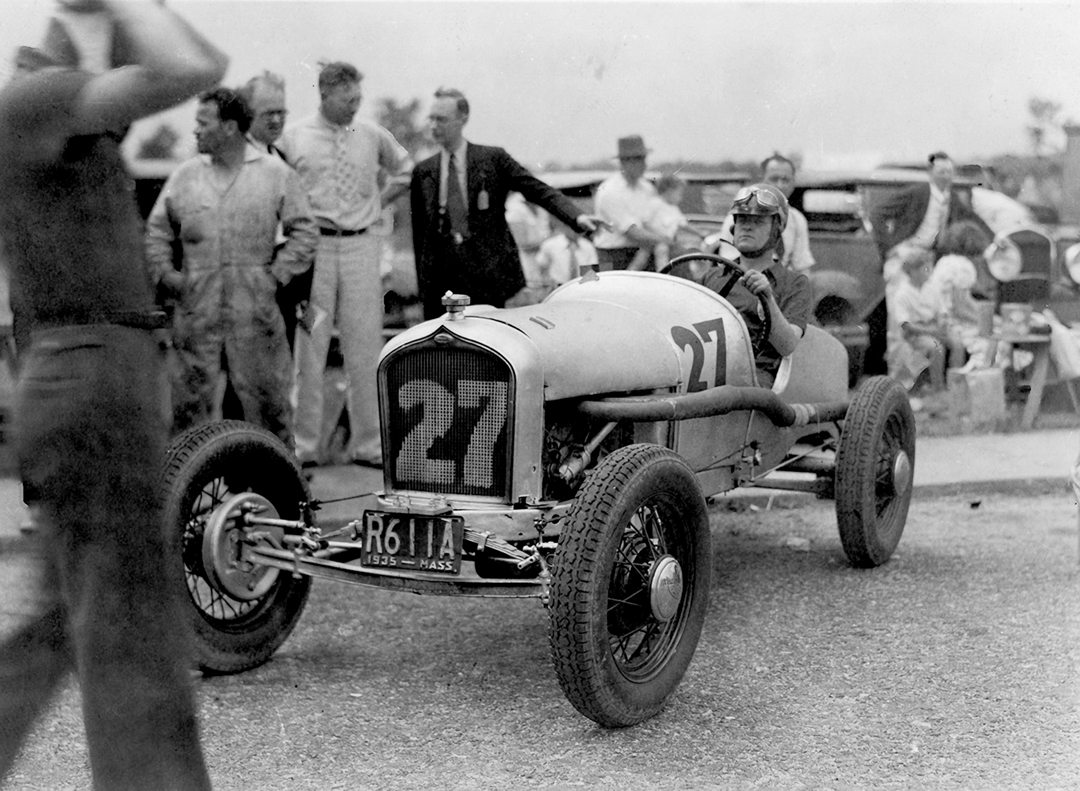

A number of events were held at the new course, as well as its counterpart, Wayland, in the Boston area. The later circuit had the advantage of being closer to a large city, drawing crowds of up to 1,500 paying spectators. One of the participants at Wayland was John Rueter. Already an enthusiastic spectator at the Sleepy Hollow events, he decided to jump into racing in a worn out Brescia Bugatti.

It was this Bugatti that introduced John Rueter to the Oak Hill Garage and Lemuel Ladd. At the time, the Oak Hill Garage was a center for racing activity in the Boston area, supplementing racing with work on neighborhood trucks. Rueter placed the car in the hands of Ladd and waited for its rehabilitation. After some practice and a race or two, Rueter considered himself to be quite the serious driver. Despite this, during an event at Wayland, he took a turn way too fast. After regaining consciousness(!), he was told that he had flipped the Bugatti three times with only a broken windshield and all four tires peeled off the rims to show for it. Rueter did not fare nearly as well as the Bugatti, coming away with several broken ribs.

As 1934 ended, Rueter got a last chance to race the Bugatti on a true paved road course, which wound 3.3-miles through the streets of Briarcliff Manor, New York. In a race marked with a great deal of attrition, Rueter and the Bugatti did finish, but way down in the field.

Selling the Bugatti and his 1924 Locomobile, Rueter went in search of a new racecar.

He ran across an ad in a local Boston paper for a Model T Ford dirt track racer, for sale out of a warehouse. The racer was disassembled, packed in crates, and had never been used. Not being allowed to open the crates, Rueter bought everything on faith and had the crates delivered to the Oak Hill Garage. What they found, when Lem Ladd opened everything, was a kit for a dirt track racer that needed a Model T as part of the equation. Off they went to the local junkyard for a usable Model T. With the T purchased for less than the price of the Dirt Track kit, they returned to Oak Hill and started putting the machine together. After a few days they had what Rueter called “A poor man’s Mercer Raceabout.”

One of the first things that became obvious after completion was that the tires included in the kit were shot; they proceeded to blow out one after the other at very low speeds. Trying again with new tires, they realized that the speed at which the old tires blew was all the car had.

So the next step was more power. Another trip to the junkyard and a Ford V8 was added to the formula. The next race was to be contested at Marston’s Mills on Cape Cod, even though the racer was still under construction. The race started and the Ford special had still not arrived, but these were less formal times. As soon as Rueter arrived with his car, he slotted himself in behind a group of cars already in the midst of their race, unbeknownst to any of the officials. When he came to the main straight he stood on it, and almost immediately the V8’s power overcame the Model T’s rear end—with predictable results. For that he held the record for the shortest run at Marston’s Mills circuit. This would prove the end of “The Old Grey Mare” MK1. Rueter realized that major changes were going to have to be carried out to create a truly competitive machine.

The times they were a-changing; racing on small private dirt tracks was no longer the norm, racing on paved public roads was the latest thing. As a result, the smaller underpowered cars of the “Overlook” days were not going to cut it. With victories in mind, Rueter set Lem Ladd loose to create a new and improved Old Grey Mare.

The first order of business was to scrap everything from the earlier car except the engine. Next, multiple trips to the junk yard ensued to source usable parts. First came a Whippet chassis, to which the engine, transmission, steering and running gear were installed. The steering was slightly modified Ford, as was the driveline. The driveshaft was shortened considerably and the rear axle was cut and welded to give the car a “crab track,” a setup that makes the rear track somewhat narrower than the front—this was considered the “hot setup” of the time.

Soon they had a rolling chassis; next they installed the cut-down Ford radiator to fit in the proposed bodywork. A few shake-down runs in the bare chassis proved they were on the right track, so it was on to body work. Unfortunately, there were no body fabricators at the Oak Hill Garage, so back to the junkyard, where a radiator shell from a Marmon Straight 8 was found, cut, chromed, and attached to the evolving racer. An ex-Indianapolis Hudson body was purchased, but found to be too heavy, so a rudimentary cowl of chromoly tubes and sheet aluminum was made. The hood was, luckily, an easy addition. The design for the tail of the Mare was beyond the capabilities of the Oak Hill staff, so a box-like structure was used at the time.

Rueter and Ladd then started a series of road tests to work out the bugs. They found, by way of the local feed and grain merchant’s scales, that the Mare weighed a shade over 1,350-pounds, with nearly a 50/50 weight distribution. They knew the Ford brakes would never really be effective—they were getting as much cooling as possible with the open-wheel design—so after a few laps they would have to rely on help from the gearbox to slow the car down. In addition, the Ford split-skirt pistons were not up to handling any engine speeds above 4,500 rpm—the pistons would simply disintegrate. As a result, a mold was made and solid-skirt pistons were cast specifically for the engine. Ignition break-up was solved by installing a Scintilla Vertex magneto.

Cooling was a constant problem, and initially incorrectly solved by speeding up the water pumps. This only created cavitation and steam pockets that resulted in many a cracked cylinder head. After that, they left the engine pretty much alone with a single carburetor and stock cam.

The car had good low-end torque, if not great top end, but this was a plus for the tracks on which they were running, as they placed more of a premium on acceleration than top speed. The Mare was able to capture a number of lap records, even if it was not a frequent finisher.

As the second running of the Briarcliff race, in June of 1935, was looming ahead, a violent shimmy in the front end of the Mare was discovered at speeds over 90 mph. The shimmy was so violent there was fear of the wheels being ripped off the car. Careful examination revealed that both front wheels were vibrating in unison. Lem Ladd, a very inventive individual, proposed a solution: each front wheel would have a slightly different caster, camber and toe-in to get rid of this synchronized shimmy. The solution worked perfectly. Yet arriving for the Briarcliff race with a well turned out pit crew in matching uniforms, the Mare almost didn’t pass tech inspection; the officials were taken aback due to the contrasting angles of the front wheels! Given the explanation for the modification, and after observing the Mare at speed for a few laps, the design was eventually accepted.

The next hurdle was the mercurial Miles Collier, who was having a bad day—he didn’t like the rough look of the Mare. After much argument and hostility, the entry was finally accepted, probably due to the neatly uniformed crew and the small-entry field. With steamed-up goggles from the heat of the day and multiple pit stops to cool the steaming Mare, Rueter was happy to finish in a very respectable 6th place, and found that when running, he was one of the fastest cars on course. However, this event proved to be the last racing on public roads at Briarcliff. The next challenge for Rueter and the Mare would be “The Climb to the Clouds” on the Mt. Washington toll road.

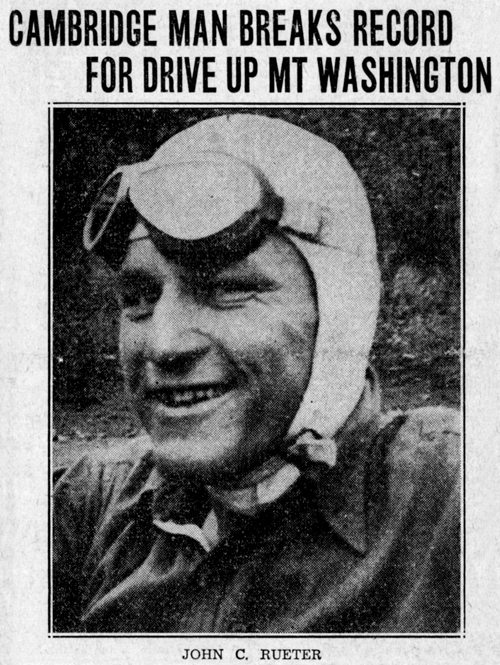

Many professional drivers with sponsored cars had made attempts to break records on Mt. Washington. This would be the first comparison between the gentleman racers of ARCA and the pros of the time. Finding nothing wrong with the Mare after Briarcliff, and with no new ideas to remedy the overheating, the car was left alone. As Lem Ladd was not joining the team for the hillclimb, and Mt. Washington was only 100 miles from Boston, Rueter and a friend simply wired on garage tags and headlights and headed north.

Arriving at the mountain, Rueter and the Mare again received a rather cool welcome from the ARCA crowd. While others were changing rear-end ratios and tire sizes, Rueter signed in and went to his room and took a nap.

One practice run was allowed later that day to get an idea of the layout of the hill. Come race day, a number of contestants had not made it to the hill, so only five cars started in the event. Rueter got a very good start and did his best not to lose too much time from wheelspin on the loose gravel road. Within two miles of the finish, he ran into a dense fog, and was barely able to see in front of the Mare, but kept pushing hard. Before he knew it, he was at the parking lot for the “Tip-Top” house, the finish line for the climb. After the last car was in it was announced that Rueter had made his run in 12:46:25, beating all previous records, both amateur and professional.

Returning to the Oak Hill Garage after their triumph at Mt. Washington, Rueter found the Brescia Bugatti that started with him on his racing journey had been returned to the garage to be broken down and sold for parts. The tail section was immediately purchased and grafted onto the Mare, which created a much more sporty derriére. In the end, parts from 19 different cars would become part of the “Mare.” A few more events with the usual overheating problems rounded out the 1935 season.

The 1936 campaign started in May with a disastrous trip to a race in Memphis, Tennessee, arranged by the Collier brothers. Not only did they have to replace tires multiple times on their trailer during the trip, but they found on arrival that the design of the trailer had destroyed the tires on the Mare, as well. With new tires mounted on the racer, Rueter was asked if his traveling companion Erik Stetson could race their Auburn Speedster tow-car to help fill out the field.

Starting from the back Rueter and the Mare had lapped the entire field twice before stopping on course from overheating. Returning to the pits, insult was added to injury when Rueter discovered that earlier in the race, Stetson had slid on oil, hitting a telegraph pole and doing major damage to the Auburn.

After making the tow-car cum racecar roadworthy again, the trip back to Boston began, only to be halted in Pulaski, Virginia, until money could be wired for the pair to fill their stomachs—and the fuel tank of the Auburn—to get them the rest of the way home.

The second “Climb to the Clouds” was next on the agenda, which would prove to be Rueter’s final race with the Mare and ARCA. Much publicity surrounded the race because of Rueter’s previous year’s victory, so there was a larger field of entrants, plus a great many more spectators.

At the start, Rueter put his foot into it; after some major histrionics in the first turn that scattered many a spectator, the now well-known overheating made itself evident. Rueter could only post the 3rd-fastest time of day.

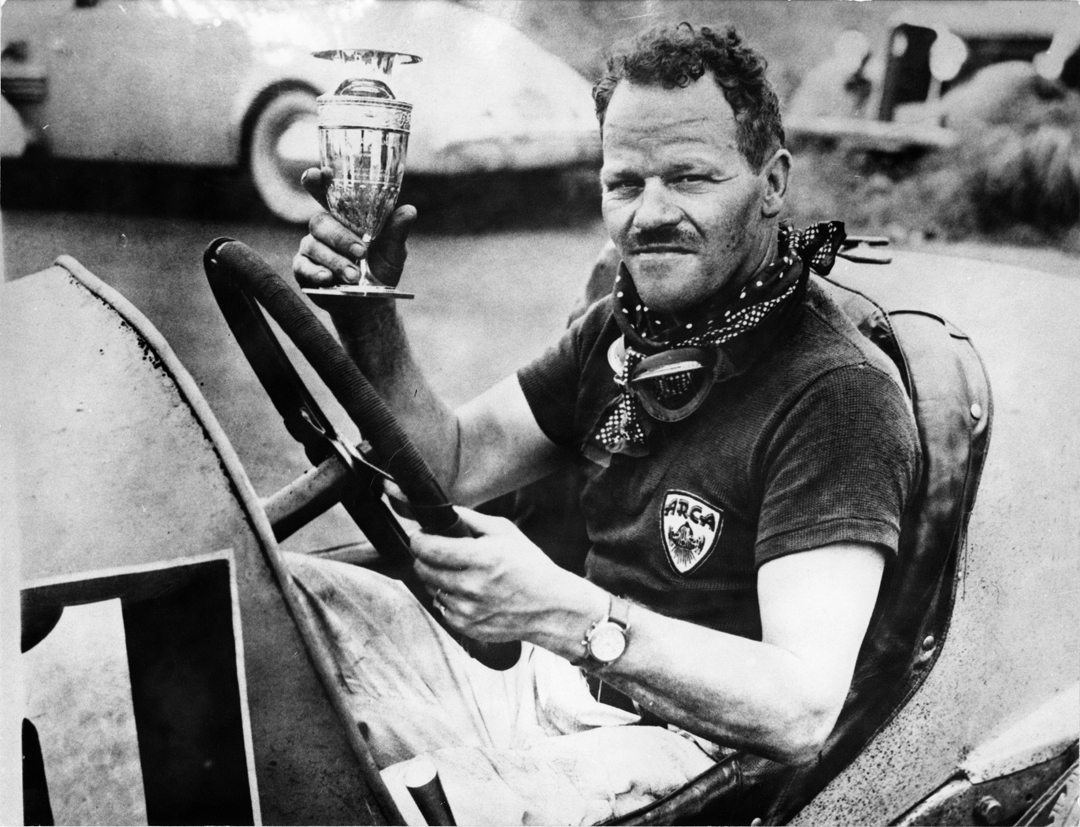

In the fall of ’36, Rueter moved with his wife to Savannah, Georgia. The Mare then became the mount of Lem Ladd, her creator.

Lem was no blueblood. He was a master mechanic and excellent racing driver who took care of many of the Boston-area ARCA members’ cars. Despite his modest background, he was embraced by the club, even though he and the Mare won multiple races against his Bostonian and Main Line clients. This included a new record at the 1938 Mt. Washington hillclimb of 12:17:6 that would stand until 1953. For their victories, they were awarded the coveted race number “1” for the 1939 season.

The 1940 season ended at the annual dinner in November with much gaiety and anticipation of the coming year, but the 1941 season was not to be. With many ARCA members joining the military, and gasoline shortages, races were cancelled one after another, with the attack on Pearl Harbor sealing ARCA’s fate. A letter to the members from club President George Rand dated December 9 suspended all of ARCA’s activities, with a hope of continuing in the future. Unfortunately, that was never to be.

Lem, while still stationed overseas, sold the Old Grey Mare to George Weaver to run in the newly created SCCA. Weaver, who built the Thompson Raceway, encouraged young members to borrow the Mare for various events. One of these borrowers was Bill Leith, who not only competed in the Mare, but once used the racer as transportation between Dedham, Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island, to pick up a date! The young lady was, apparently, not a racing fan, so there was no second evening out.

The Mare continued to compete in the SCCA up to 1952 where it took 2nd place in the Seneca Cup at Watkins Glen, behind John Fitch in a C-Type Jaguar. By 1954, the Mare was a very tired old racer, with cracks starting to show in the chassis. Then owner Hugh Ware, who had run the car in some SCCA club events, felt she was too far gone to race or repair, so she was retired behind his garage. There she sat for 17 years with parts being progressively scavenged off her as time went by. In 1971, Doug Philbrook, an affiliate of the Mt. Washington toll road, heard about her fate and rescued the Mare in the hopes of returning her to her former glory and displaying her at the hill.

Sandy Leith, the son of Bill Leith, had been told stories of the Old Grey Mare as a child and longed to know what had become of her. By 1978, he found Doug Philbrook and initiated a multi-year correspondence in hopes of obtaining and restoring the car and bringing it back to Mt. Washington. For many years, the answer was always negative; Philbrook wanted to restore the Mare himself.

Then on December 11, 1995, Sandy got an early Christmas present. The car was finally his. Having just picked up a Bugatti special, Sandy was not ready to take on the restoration without help. Therefore, mechanic Benjamin Bragg IV was brought in as an equal partner to help with the resurrection.

It would still be a few years before work could start on the Mare, as other projects—and life—came first. Time passed; eventually, 2004—the centennial of the hillclimb at Mt. Washington—loomed. Work started in earnest in November of 2003 to have the OGM ready for the “Climb to the Clouds.”

On July 9, 2004, Sandy Leith brought the Mare to the starting line at the base of Mt. Washington, almost 69 years to the day of its first run up the hill, and 50 years since the car had last seen the light of day.

Sandy was ecstatic, from its first test drive in Woburn the day before, to two runs on the mountain in the following days, the old warhorse ran well and felt great. It was also a very emotional time for Leith, driving a car once raced by his father and fulfilling a promise made to Doug Philbrook to bring the Mare back to Mt. Washington. She was back, alive and kicking!

In 2005, the Mare was invited for a showing at the Monterey Historics and the Lime Rock Vintage Fall Festival, in the Rolex tent featuring “The Great American Specials.”

In 2007, Sandy was given an offer too good to pass up, a barn-find 1937 BMW 328. As a result, Ben took over full custodianship of the Mare, continuing the driver-mechanic tradition started by Lem Ladd, the car’s creator. Ben continues to run the OGM in the VSCCA, climbing mountains and running wheel-to-wheel with the same exotic machines she was used to competing against back in the ARCA days.

Driving the Old Grey Mare

Getting into the Mare during a break at the Lime Rock Historics, I am faced with the bare minimum of gauges a racer would need—tachometer, oil pressure, water temp and amperes mounted in a piece of sheet aluminum.

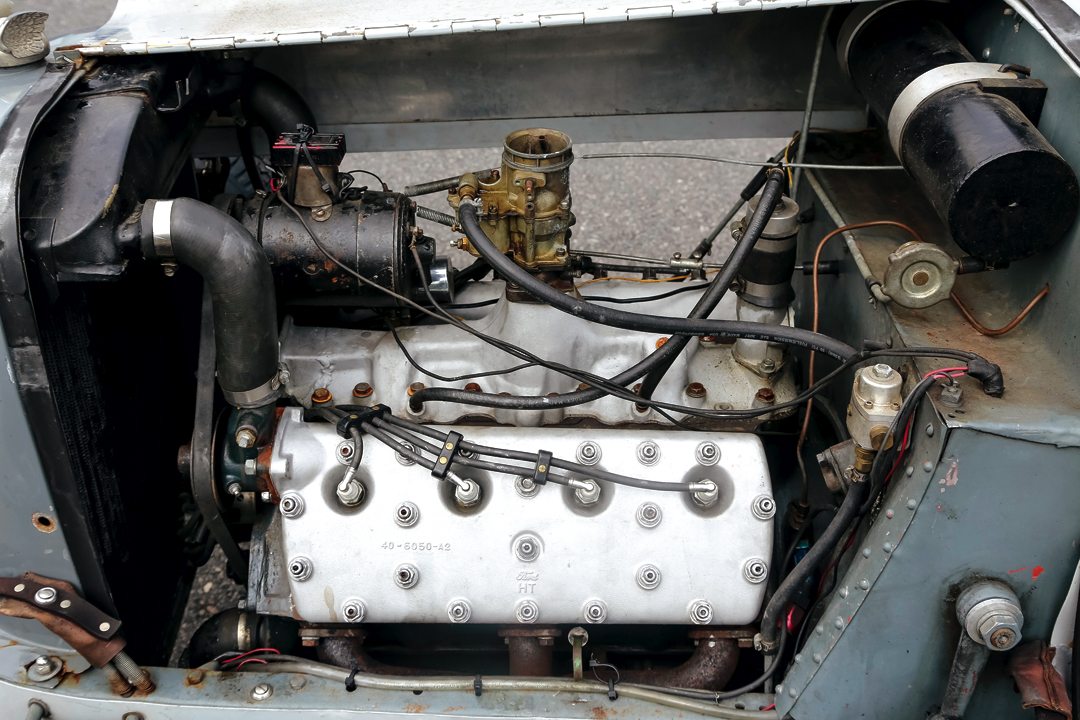

It’s a very spartan cockpit, with only a lap belt to hold you in, and a rope-wrapped steering wheel to hold on to. The engine is still a first series, Ford 21-stud, V8, mated to a three-speed Ford gearbox running to a stock ’34 Ford rear end, with 4:11 gears. The overheating is a thing of the past, as the car now has a modern reproduction ’34 Ford radiator with a 15-pound pressure cap. The piston tops and combustion chambers have also been ceramic coated to slow down heat transfer. With a bit of race preparation, the Mare is now putting out close to 190 horsepower, with all the torque one might need.

Driving the Mare in a normal manner slows you down—you have to drive it with the throttle, go fast into a turn to create understeer, then get on the gas to generate a very predictable drift—then you just hang on and enjoy the ride!

The Old Grey Mare has had a long and colorful life, proving that with a little American ingenuity and not much money, a machine could be built that matched and beat many of the great European marques of the time. In fact, it is still doing that today, and Ben Bragg and his mount show no signs of slowing down.

All one can say in reflection is, The Old Grey Mare is still what she used to be.

SPECIFICATIONS

Wheelbase: 91-inches

Front track: 60-inches

Rear track: 60-inches

Body length: 150-inches

Body width: 40-inches

Height: 40-inches

Weight: 1600 pounds

Fuel: 8 gallons

Suspension: Transverse leaf springs front and rear

Brakes: Mechanical, 1934 Ford drums

Gearbox: 1934 Ford 3-speed

Engine: 1934 Ford flathead V8

Bore: 3.16-inches

Stroke: 4.8-inches

Carburetor: Single two-barrel Holley

Compression: 8.5 to 1

Horsepower: 150-hp

Top speed: 106-mph