Karl Abarth was a magician. A waver of wands whose magic brought the exquisite pleasure of higher-performance motoring and motor racing to men and women of modest means. His speciality was conversion. And he turned the Fiat 500 and 600 low-powered tin boxes into teeth-gnashing, tire-smoking predators that won thousands of races all over the world. But it didn’t stop there. He built cars that broke world land-speed records, single- and two-seater racers, and short runs of road cars exquisitely bodied by some of the greatest Italian stylists of the day. In the late Sixties, he even built a 600-hp V-12 that was to have clashed with the Ferraris at the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

To own a Fiat Abarth road car was to be a cut above the next door neighbor and his flaccid factory Fiat. It was a desire for more, for better in the frugal gray world of postwar renaissance Italy.

Years later, mainly due to the genius of Mario Colucci, who stayed on with Fiat after the demise of Abarth & Co., factory Lancias and 131s took the magician’s legacy to even greater distinction by winning world rally championships time and again.

Abarth was Viennese, born in the capital of the Hapsburg Empire when it was still an empire on November 15, 1908. From childhood, he was passionate about all things mechanical and, although he came from a middle-class Austrian family, he worked on the shop floor in his youth, helping to build Thun motorcycles. It was there that he learned about chassis technology and the internal combustion engine. Soon, he began to race, and he was good at it. A technical genius in the making, he designed and built his own bike when he was 21 but had a serious accident and shattered a knee, so his doctors said his racing days were over. He took a brief interest in marathons and raced a 500-cc Sunbeam 355 miles from Vienna, over the Thurn Pass to Innsbruck in a record 8 hours 37 minutes. Then he raced the famous Orient Express train 832 miles from Ostend to Vienna on the Sunbeam and beat the charismatic locomotive.

But he yearned to race bikes again and came up with a bright idea. Why not compete with a motorcycle and sidecar, which would keep his bad knee out of harm’s way and give him back that old competitive stimulation? So he upped the power output in his Sunbeam to 600-cc, designed and built a spindly looking sidecar for it. He also asked an old sidekick of his, Joseph Holly, a talented mechanic, to ride sidecar for him, and off they went. Karl won many races and became the 1934 Austrian sidecar champion.

In the years that followed, he piled up an astounding number of bike and sidecar Grands Prix, hillclimb, and race victories. He also used his technical brilliance to design and build new exhaust systems, another sidecar, and an oscillating axle, which was the secret of his later racing success. Then he sold reproduction rights for all of them to manufacturers for a pretty penny.

The Nazis annexed Austria and marched into Vienna in 1938. Suddenly, Karl found he was living under a vicious national Socialist regime. But even that played into his hands. Vienna’s resident Italian Fascists had discovered that Abarth’s father was now an Italian citizen living in Merano and contacted Karl offering a large bag of gold to race under Italy’s colors. He accepted, so Karl became Carlo as well as an Italian citizen. He was 30 years old, rich, famous, and successful. Then, in October 1939, he had another serious accident that almost cost him his life. It certainly cost him his sidecar racing career.

Carlo spent the Second World War in Lubiana, Yugoslavia, where he worked as the technical director of an engineering firm for which he converted cars and trucks to run on natural gas instead of extremely scarce petrol. After the war, he made his way to Merano to join his father and began selling bicycles in the little south Tyrolean town, but that quickly bored him. Before the Second World War, Abarth’s wife had been the secretary to Anton Piëch, a Viennese lawyer who had married Louise Porsche, daughter of Ferdinand the designer of the prewar Auto Union racing cars, among other things. So Carlo wrote to Louise offering to become the Italian representative of the company she and her brother Ferry ran from Gmünd, Austria. That was when Abarth got wind of Professor Ferdinand Porsche’s design for a revolutionary new, 12-cylinder, 1500-cc, supercharged, four-wheel drive Grand Prix racing car. Carlo interested Tazio Nuvolari in the project, as the mantovano volante was looking for a car with which to make his postwar comeback. A meeting took place between Abarth, Piero Dusio the Cisitalia boss and gentleman driver, and Piero Taruffi. Dusio, who was already producing small displacement racing and road cars, acquired the rights to the futuristic Porsche Grand Prix car design and Carlo Abarth became his motor sport director.

Only one prototype of the Porsche-Cisitalia was built and that was in 1949, soon after which a heavily overstretched Dusio ran out of money. In the meantime, Carlo set up Abarth & Co. with three partners and acquired the Cisitalia leftovers, rescuing what he could from the now-defunct company. Abarth & Co. was to design and build short production runs of road cars, racers, and a vast range of go-faster components including inlet manifolds and exhaust systems, devised by Carlo, to pep up the swarms of boring little utility sedans that roamed Italy. And he set up his own racing team. Among the mixed bag he acquired in the Cisitalia takeover was a handful of cars—including a couple of 204A roadsters—which he raced in 1949 and 1950, driven by people like Piero Taruffi, Antonio Pucci, Franco Cortese, and even the great Tazio Nuvolari. They won 27 lesser races and hillclimbs, including the 1950 ascent of Monte Pellegrino in Sicily, Tazio Nuvolari’s last victory.

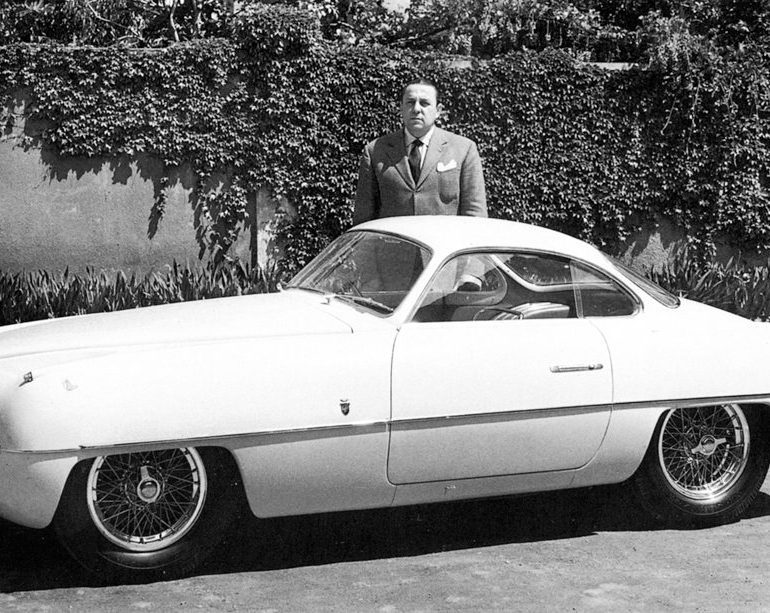

While all this was going on, Abarth deftly used his motor racing successes to sell his go-faster components to people who wanted a bit more “oomph” from their underpowered road cars. And he sold a small production run of the much-revised Cisitalia 204A, for which the now-famous scorpion, Carlo’s zodiac sign, was fashioned into his company’s badge. But motor racing was expensive, so Carlo decided to pull his horns in and take a five-year break from the sport, starting in 1951. He began to export his exhaust systems to other European countries. And Abarth worked closely with a famous coterie of Italian body stylists of the day, like Bertone, Ghia, Pininfarina, and Zagato, as he came up with new ideas to wring better performance out of the chassis and engines of the slow, little, production cars. They became Abarths, and one of the wildest of these was a three-headlight, droop-snoot coupe based on the Fiat 1400 designed by Bertone’s resident “lunatic” Franco Scaglione, diviner of the extreme, the exceptionally exotic in body styles. It was called the Abarth 1500 and stunned all who saw it at the 1952 Turin Motor Show. His next candidate for improvement was Fiat’s 1100-103, which, with the help of Ghia, he transformed from a slow, boxy little family sedan into a sleek two-seater coupe of great elegance and almost double the original’s power output.

Carlo Abarth was no car manufacturer but a transformer of numbingly boring family machinery—mainly Fiats but occasionally Alfa Romeos and Simcas—into a whole series of beautifully designed, really quick coupes, roadsters, and racers. His stunning work on Fiat basics inched him further into the orbit of Italy’s biggest motor manufacturer, so he already had an impressive calling card in 1955, when the Fiat 600 came out. The 600 was the car that mobilized Italy after the war and had tremendous flexibility for which Carlo Abarth developed a 750-cc engine that all but doubled the 600’s power output, helped along by a custom-designed exhaust system and inlet manifold plus an array of Zagato bodies. The Fiat Abarth 750 GT, as the car was called, was a huge success, and so was the go-faster equipment motorists could simply bolt on to their bog standard Fiat 600s to give the 21-hp production car a sting in its tail.

Soon, young bucks were keen to spread their wings and go racing with their 750s. Ten of them entered the 1956 Mille Miglia and one of them won the 750-cc category of the Special Touring class, driven by Domenico Ogna. More success came fast, so that by the end of 1957, the 750 GT had won no fewer than 54 races in Italy, Switzerland, and Belgium.

Photo: Courtesy of Giorgio Nada Editore

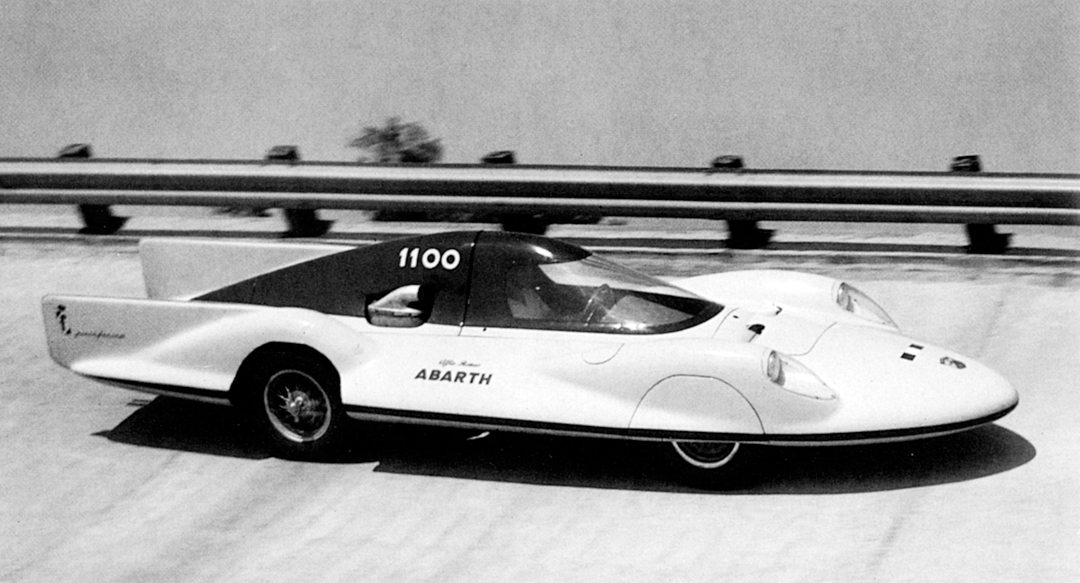

Then there was record breaking. Between June 1956 and October 30, 1966 sleek slivers of cars based almost entirely on Abarth-modified Fiat machinery wrapped in highly individualistic bodies by Bertone and Pininfarina broke no fewer than 113 world and international speed and endurance records on the full at the Monza circuit. They were driven by a wide range of hotshoes, including Carlo Abarth himself, legendary motor sport photographer and sometime racer Bernard Cahier, journalist and Le Mans winner the late Paul Frère, body-stylist Elio Zagato, Grand Prix winner-to-be Giancarlo Baghetti, and Targa Florio specialist Umberto Maglioli. Their purpose was, as always, to promote Abarth cars and perpetuate the aura of outstanding high-performance engineering that Abarth & Co. personified with such panache.

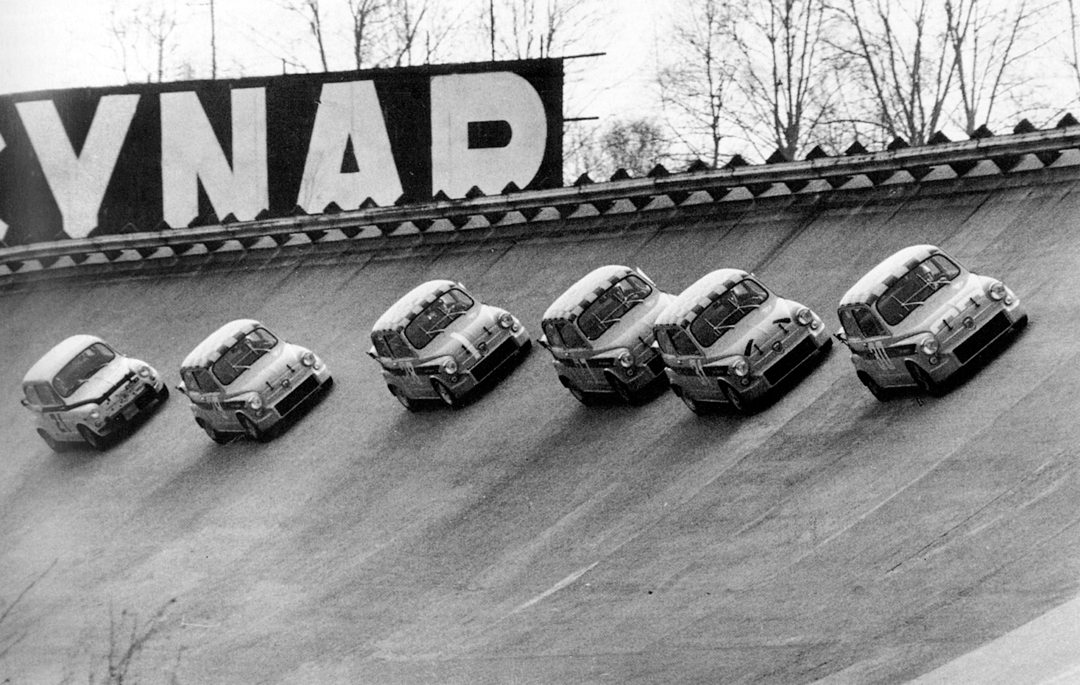

The Fiat 500 was even more spartan than its bigger sister, the 600, so much so that it did not sell well after its launch in mid-1957. It was all plastic and painted tin inside, had a crash gearbox, and an extremely noisy, two-cylinder 479-cc engine. Flushed with the success of his Fiat Abarth 750 creation, Carlo doubled the power output of the 500 by increasing its compression ratio, fitting it with a hemispheric cylinder head, his manifold and exhaust system, and improved the balance of all its moving parts. And he decided to prove the worth of his doctored 500 by running half a dozen of them at Monza 24 hours a day for seven days. The feisty little cars covered 11,302.94 miles at the incredible average speed of over 65.41 mph. While all this was going on, the visitors to Monza included some of Fiat’s directors and they saw with their own eyes how Carlo Abarth was singlehandedly transforming the limp image of their 500 into sheer excitement, a long way from the road car’s horse-and-cart perception in the market place.

Photo: Courtesy of Giorgio Nada Editore

That impressive display of engineering brilliance changed Carlo’s life for good. Soon afterward, Fiat offered him a contract under which the manufacturer agreed to pay him for every victory or successful record attempt he pulled off with Fiat Abarth cars anywhere in the world. It was a deal that would produce almost 7,500 victories in the 15 years from 1956 to 1971 to give Abarth & Co. a solid financial base and dull Fiat cars a much more exciting aura.

Carlo wanted to improve on the 750 GT and that meant the only way to go was twin overhead camshafts. So he called the great Gioachino Colombo, designer of the Alfa Romeo 158 and 159, the most successful Formula One cars up to that time. Colombo, also ex-Ferrari, had produced a version of just such an engine for the powerful Alfa Romeo Giulietta 1900, and Carlo asked the engineering genius to do the same for him.

The result was a twin-cam head with the valves at 40 degrees and the distributor drive working off a double chain, plus two Weber 32 DCL3 carburetors that put out 57 hp at 7,000 rpm. That was enough to take the light two-seater to a top speed of 112 mph. Zagato redesigned the GT and smoothed out its trademark double-hump roof. The makeover produced a smart-looking little coupe to which Carlo gave the unwieldy name of Fiat Abarth 750 Record Monza, as its engine had been previously used to break 35 international records.

Those were the cars with which Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr., who was Fiat’s East Coast concessionaire, put together an Abarth racing team for himself. Their first U.S. competition was the 1958 12 Hours of Sebring and the hairy little Fiat Abarths were a sensation. They won their class and placed 2nd, 3rd, and 4th in their category. It was an amazing performance in the pouring rain with the diminutive Italian cars continually being swamped with water from competitors up front: And it was just one of the 49 victories the GT and Monza scored that year. The cars won in Italy, Switzerland, and Germany, but also in rather more remotes places like Leopoldville in the Belgian Congo, where they won their class, as they did in the Eritrea, Venezuela, Angola, and Hawaii. The Abarth 750 even went rallying and came 1st in class in the rallies of Geneva, Megève, Sestriere, Livorno, Cagliari, and Ferrara.

Meanwhile, the tiny Fiat Abarth 500 GT made its motor racing debut and ended up winning its class in hillclimbs 14 times that year. It even won the Grand Prix of Naples.

Encouraged by his team’s success at Sebring the previous year, Franklin Roosevelt entered his cars for the Florida classic again in 1959, and again one of his Fiat Abarth 750 GTs won it class. The team then went after the Daytona Beach 100 Miles and scored the class win there, too, but with the uprated 1,000-cc Fiat Abarth 1,000 Record Monza. Then it was back to the 750 RM later in the year for the Eight Hours of Lime Rock.

Photo: Courtesy of Giorgio Nada Editore

After that, the 750 RM ruled the roost, picking off class wins at prestigious events like the 12 Hours of Monza, Italy; the Wallberg Rennen, Germany; Switzerland’s Mitholz Bergrennen; the Targa Florio in Sicily; the Mount Prilerimos hillclimb; and Circuit of Rhodes in Greece, plus a slew of victories in its homeland.

But Carlo’s attention was not exclusively focused on turning little cars into world-class winners. With the help of Allemano’s elegant body styling, he moved into the hard-nosed 2200-cc market segment with a sophisticated 2+2 coupe powered by a beefed-up Fiat 2.1-liter, six-cylinder engine that put out 135-hp and had a top speed of 122 mph. It was followed that same year by the Fiat Abarth 1600, another Allemano-designed 2+2 tin top, and rounded off the range with his own, much improved, version of the Fiat Abarth 850 Scorpion to complete his market segmentation.

A Carlo Abarth dream came true at the end of 1959. Porsche asked him to lighten the second coming of their 356, which had grown heavy with creature comforts. And so it transpired, with the birth of the Franco Scaglione–designed Carrera GTL. As with so many of Scaglione’s creations, the Abarth Porsche was way ahead of its time. It had a lower, longer, sleek-looking, hand-beaten aluminum body with an elegantly sloping, much-louvered rear end that made the original 356B seem positively ancient. But the bubble burst when Porsche declared that the finish was not up to their expectations, so only 20 examples were built, despite motor sport successes that included a class win and 10th overall in the 1960 Le Mans.

One of the most important decisions Carlo ever made was to employ Alfa Romeo TZ-designer Mario Colucci as his technical director. The man from Alfa created Abarth’s first open-top racer, with an aluminum-clad tubular steel chassis and a twin overhead camshaft engine amidships that powered the little 750 Sport Spider barchetta to a maximum speed of around 125 mph. It was the forerunner of a string of Abarth racers with twin-cam 750-, 850-, and 1,000-cc engines that were to conquer the world—literally.

And before they were let loose, all of them were personally tested by Carlo Abarth on a disused Turin airstrip before they went into production or were signed off for racing.

The Colucci-designed 1961 Fiat Abarth 850 TC and its later derivations were probably the most ubiquitous and successful of this “Fiat 600 in disguise” family. Outwardly, it may have looked like a slightly more muscular 600 with an engine cover that was clamped permanently open, but under the skin “Abarthisms” abounded. Like an irascible little 847-cc, two valves per cylinder engine with twin choke Webers that put out 93-hp at 8,400 rpm, for a top speed of almost 120 mph. At the time, it was unheard of for such a little tin box to wear disc brakes, which were almost exclusive to the supercars of the day, but the 850 TC Corsa (it stands for Touring Competizione) boasted discs front and rear. A Mini Cooper beater, if ever there was one.

Photo: Courtesy of Giorgio Nada Editore

The car was first homologated in early 1961 and it also opened the way to the 700 BA and 1,000 BA, which would wipe the floor with the opposition in the years to come, from Milan to Mexico City, Aspern to Asmara, Arkansas to Aix en Provence. They were the scourge of the Touring and Grand Touring classes from 1961 to 1964 and, like all good terriers, would never let go. Their bite eased off a little when the Abarth Simca 1300s came along to compete in a bigger-engined category, but still they dominated their own segment with ease.

But by the end of 1961, Abarth & Co. had become a victim of its own success. It was unable to build its substantial range of models in the quantity demanded by the market. That year, the Turin plant turned out 1,000 Fiat 600-bodied 850 TCs and a massive increase in production was planned for 1962. But that had to be scaled back, to provide the right kind of service for its racing-driver customers the world over. Shoddy products were never part of the Abarth DNA.

Photo: Courtesy of Giorgio Nada Editore

Simca had been producing cars since well before the Second World War and had developed a working relationship with Fiat. An old friend and Cisitalia colleague of Carlo’s, Rudy Hruska, was the technical director of the French firm and he was fascinated by the phenomenal racing success of the Fiat Abarths. So he asked the Austrian to develop a prototype based on the Simca 1,000.

In 1961, Carlo designed a brand-new, twin-cam, 1,288-cc engine for the car, with twin-choke Weber 45 DCOE carburetors and trumpets that would not have looked out of place in the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. The unit produced 125-hp at 6,000 rpm and gave the car a top speed of almost 150 mph. It was a stubby, no-nonsense little coupe designed by Mario Colucci with a radiator and cooling system up front fed by a generous scoop and a bulbous, heavily vented rear end that housed the big, muscular engine. The diminutive Franco-Italian racer won nine European events in 1962 and was well on the way to a successful career in the sport.

Photo: Courtesy of Giorgio Nada Editore

Better still was Fiat Abarth. They became the year’s World Champion Constructor in the up-to-1,000-cc class. In all, Abarth scored a total of 234 class wins; it came 1st overall in seven races, and took three Italian championships. The car responsible for most of this great success was the 1,000 Bialbero designed by Mario Colucci that was able to generate a top speed of 150 mph. The car was the centerpiece of Abarth’s 1962 Turin Motor Show stand, which brandished a huge reproduction of the world championship plaque in the middle of the company’s stand.

Carlo Abarth was a tough guy who ruled his fiefdom as one would expect from a highly successful man of Teutonic descent. He defended his convictions to the death, figuratively speaking, but his technical director Mario Colucci, who came in for a lot of Abarth’s abuse in his day, was no pushover. When they clashed, it was scientific precision colliding with Carlo’s 30 years of instinctive engineering brilliance and experience. But science usually won the day.

Photo: Courtesy of Giorgio Nada Editore

Although the Fiat Abarths were by far the biggest winners in Carlo’s stable, the Simcas began to make their mark, with most prestigious wins of the Grand Touring class for 1,300-cc cars in the 1963 12 Hours of Sebring, driven by Swiss hillclimb-expert Tommy Spychiger, Mercedes-Benz hero Hans Herrmann, and Belgian star Teddy Pilette. Another was Teddy Pilette’s outstanding class victory in the Grand Prix of Berlin at the super-fast Avus circuit. In all, the Abarth Simca 1,300 won the staggering total of 77 races, rallies, and hillclimbs in 1963, only its second year of competition.

Abarths like the 595, 695, 700 BA, 850 TC, 1,000, OT 1,000, 1,300, 1,600, 2,000, 3,000, and a host of others took their toll of motor racing. They really did win a staggering 7,500 outright and class victories all over the world in the company’s brief 15-year lifespan. Occasionally, the cars were driven by stars like Hans Herrmann and Lorenzo Bandini, but by far the largest number of Abarth victories were scored by an army of ordinary people.

And that is how the Abarth bandwagon rolled on for another seven years, with reps, insurance salesmen, office workers, and the like paying peanuts for the thrill and excitement of pitting their Abarth-modified little sedans against the rest of the world. The people who didn’t make it to the track or plainly didn’t want to race got a huge kick out of fitting their small Fiat road cars with Abarth go-faster components. And those had to include the brackets that kept the racing cars’ rear-engine covers open, which impressed the hell out of the girls!

Even in their last year of competition, Carlo Abarth and Mario Colucci still developed and fielded amazing cars, like the 1,000 Bi-Posto Corse, a sexy, wedge-shaped device with a fierce 982-cc engine that put out 120 hp at 8,200 rpm and took the car to a top speed of 140 mph; a 3,000 prototype, a 2,968-cc monster that generated 355 hp at 8,200 rpm for a maximum of 190 mph; the 2,000 Sport, with a 1,946-cc engine responsible for putting out 260 hp at 8,800 rpm for a top speed of over 170 mph; and they breathed on another boring little box of an Italian road car called the Autobianchi A112, to coax it into almost doubling its top speed to almost 130 mph, a young buck’s dream come true.

In 1971, much to his disdain, Abarth was politically maneuvered into designing and building the cars for the 1972 Formula Italia, the cadet racing scheme run by the CSAI, the Italian motor sport governing body. They were single seaters powered by a much-modified 1,608-cc Fiat 124 S engine, with a Lancia Fulvia gearbox and Fiat 125 disc brakes. Fifty of them were built and sold at a knock-down price to young men with racing ambitions.

The late Sixties and Seventies were years of Italian industrial strife, which gave Abarth nightmares when trying to deliver cars to circuits on time, as he did his best to outfox the union pickets at his Turin factory’s gates. That had the knock-on effect of weakening the company’s finances. So, perhaps not altogether unexpectedly, Fiat stepped in and took over Abarth & Co. Racing was stopped immediately and Abarth became a Fiat motor sport satellite. Carlo was employed as a consultant and one of Abarth’s lieutenants, Renzo Avedano, became managing director of the company. The brilliant Mario Colucci stayed on, and Fiat’s own rally department was transferred to the Abarth plant, where the labor force was halved.

Carlo plodded on as a consultant for a while, but he spent an increasing amount of time in his hometown of Vienna, where he died on October 23, 1979. At the end of 1981, Abarth & Co. was absorbed into the Fiat Auto S.P.A. empire, where it remained more or less dormant for almost 30 years. Meanwhile, the late Mario Colucci contributed greatly to the Lancia and Fiat world rally championships of the Seventies and Eighties, a tribute to his technological genius and the Abarth pedigree.

Today, though, the Abarth name has been dusted off and pressed into service again. Fiat is successfully rallying its new Punto Abarth, another little tin box converted into an Italian Rally Championship winner. And in 2008 the group introduced its smart, quick, 500 Abarth road car, a little Mom and Pop sedan made great by some Abarth treatment.

The magic lives on.