1958 Lola Mk1

The Broadley cousins were racing enthusiasts from an early age. Both built and raced Austin specials before setting about in 1956 to construct something to compete with the new Lotus VI, being built and raced by one Colin Chapman. Their original idea had been to buy a Lotus VI, but the cost was prohibitive, so they started on their own car, a Ford-based special, which was the first car to carry the Lola name. This “Special” utilized the Ford 1172 cc side-valve engine, which had been used to great effect in many homemade racers of the time. It was with this first car that Eric Broadley honed the skills that would allow him to challenge the Chapmans of the time.

The Ford Special made its debut in 1957 and had a number of successes. Thanks, in part, to Broadley’s painstaking approach to engine development (he even fashioned his own lightened concave-bottomed tappets, which improved valve lift and acceleration), the Special started beating the new Lotus 11 later in 1957 and began a pattern that was to continue for many years.

At the end of 1957, Eric Broadley decided to enter the growing arena of sports car racing with a clear aim: to beat Chapman’s Lotus. With all the cars in the small sports car class now using the same widely available Coventry Climax engine, Broadley established a strategy to build a better car and concentrated on stiffening the chassis and eliminating the heavy deDion rear suspension frequently used by other builders. In a period of only eight months, the Lola Mk1 prototype was designed, constructed and made its first racing appearance.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

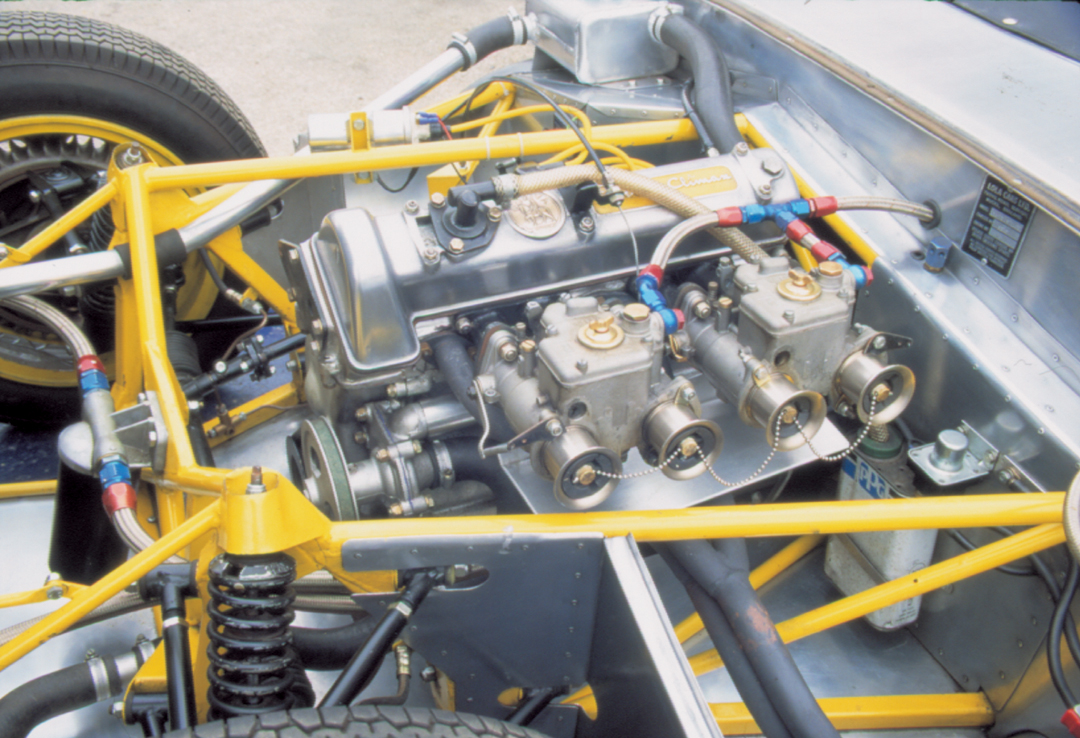

Author and Lola Mk1 expert David Pratley carefully chronicled the Mk1 development process: “The suspension layout of the new car was designed to feed cornering loads into the tubular chassis over a wide base, and for the chassis to absorb those loads progressively into the structure. The basis for the chassis’ multi-tube structure was to provide stiffness at the mounting points for the major components. Broadley’s work on triangulating the chassis tubes formed the basis of a strong, yet light, center-chassis area, using as it did a mix of 1” square and round tubes. Detailed thought was given to exactly how loads could be fed into the chassis at various points which retained lightness and robustness at the same time.”

Pratley continues: “The center section of the chassis was composed of the engine and scuttle bulkheads which were cross-coupled together in a number of planes. At one point the engine bulkhead cranked back, to accommodate the rear of the engine, and was braced in a seven tube mounting point. Because of the good rigidity between these bulkheads, the cockpit sides were relatively low without compromising the structure… Sif-bronze welding was used for the 20-gauge mild steel seamless tubing in the chassis, making for a light structure weighing in at only just over 60 lbs.”

In the Mk1 prototype, the front suspension wishbones were of equal length and were mated to Standard Triumph uprights and inner Metalastik bushings. This combination was not adjustable. The rear was the result of much drawing board experimentation and consisted of a top wishbone linking the trailing arm and the driveshaft to get around the nemesis of spline lock-up, which was characteristic of many independent suspensions of the day. The overall Broadley suspension design was very forward looking and variations of it found their way onto the F1 cars of the early 1960s.

Photo: Peter Collins

For power, the Mk1 prototype originally used the 1100 cc Coventry Climax FWA fitted with 1” SU carbs to save the costly expense of Webers. The gearbox was from the Austin A30/35, or as more commonly known later, the Sprite gearbox – a unit which was strong and could accommodate close ratio gears. The car had 15” magnesium cast wheels from Cooper, common to many current single-seaters, in which Broadley modified the roller bearing positioning to further reduce unsprung weight. Steering came from a Morris Minor with lock-to-lock consisting of one-and-three-quarter turns. The brakes were in contrast to the trend of the time, Broadley opted to use drums instead of the popular new disc brakes. His thinking was that a light car in short races wouldn’t be disadvantaged by drums. Hence the TR-2 drum units were mounted outboard at the front and inboard at the rear, originally measuring 10” x 2.25” at the front and 9” x 1.75” in the rear.

One might have thought the bodywork, which was going to cover the Lola’s then high-tech mechanicals would have been the result of early aerodynamic research and much thought. The truth is that Broadley went to see Maurice Gomm about a body and found a nose section that had been made up for a Tojeiro that fitted almost perfectly. The rear section was then fabricated to match the front, with the good-looking aluminum body opening from hook hinges providing full access to the internals. Rounding out the package was a 5.5-gallon fuel tank fitted in the left side of the car to offset the driver’s weight. Remarkably, the total weight of the prototype, (which in its current form has been somewhat improved from the original specs), is a mere 830 pounds with oil and water – some 60-65 pounds lighter than the comparable Lotus of the period in equal trim.

All of Broadley’s meticulous work resulted in a 50-50 front/rear weight distribution in a car with a 7’ 1” wheelbase and 48” track. Broadley’s intention was to produce a very lightweight machine with considerable power, superb handling and a touch of understeer. He achieved it.

Photo: Peter Collins

Racing History

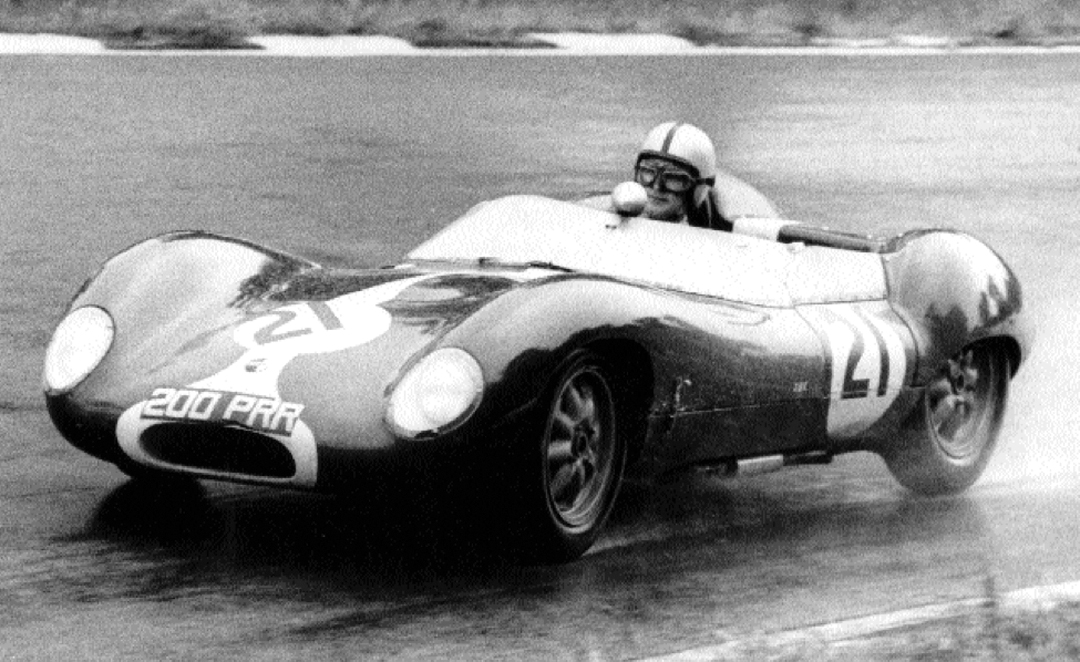

The prototype Mk1 had its first race as a “Broadley Special” at Crystal Palace, that wonderful little London circuit, in July 1958. With no prior testing, Broadley drove cautiously in the first heat to finish near the back of the pack, but as he got used to the car, his lap times in the second heat were not far off those of the winner, the big Lister Jaguar of Ivor Bueb. Running as a Lola three weeks later, Eric Broadley raced at Snetterton in a hard-fought 1100 cc sports car race, which saw victory go to the Lotus 11 of Keith Green, with Broadley’s Lola second, after a spin. The signs were becoming clear as to what was to follow. At Brands Hatch in August, the Lola was second in the first heat, won the second heat, and was shoved out of the final, after setting the first sub-one minute lap at the Kent circuit for sports cars. The press acclaimed the car’s superior handling and its ability to put the Climax engine’s power to the ground.

Broadley then rolled the car in a minor race at Goodwood and took a full two weeks to repair the damage, finishing just in time for the Tourist Trophy 4-hour race at the same circuit. With Peter Gammons codriving, the Lola was quick but fragile, finishing well down after setting a new class lap record in a race won by Stirling Moss and Tony Brooks in an Aston Martin DBR1, with the 1100 cc class going to a Lotus 11. (One Carl Haas, later to be an American agent for Lola, was driving an Elva in the same race.)

Towards the end of 1958, the Lola was getting a lot of attention. Up-and-coming sports car driver Peter Ashdown was offered a test drive and, having raced for both Lotus and Elva, was not only quick but was emphatic in his view that the Lola was better built. Ashdown also felt that with strengthened wishbones, the Lola was also a much safer car than the Lotus. At a time when Broadley was thinking of building four customer cars for 1959, he left his full-time job and set up shop in new premises in Byfleet, selling the Mk1 prototype to former codriver Peter Gammons for 1200 pounds. In the last race of the season, the December 26 Boxing Day race at Brands Hatch, Graham Hill, in a Lotus Mk VII, won from Gammons, driving the prototype, with David Piper’s Lotus 11 third and Ashdown, having his last race for Lotus before becoming a 1959 Lola works driver, fourth.

Photo: Peter Collins

Broadley went into production to construct some 40 Lola Mk1 sports racers from 1959 to 1962. I say some because the exact number is uncertain and depends upon whether one counts chassis as complete cars. Thanks to the work of some dedicated Lola enthusiasts, the histories of virtually all the cars which went on to beat Lotus and Elva (both at the time and in later vintage races), are well recorded.

Meanwhile, Broadley, Ashdown and Gammons in the prototype campaigned in 1959 under the works banner, were immensely successful, winning many races and often taking the first three places, beating the Lotus opposition regularly and attracting more and more customers. Gammons swapped the prototype for a newer car, and the prototype then had several owners over the next few years: G. Pitt in 1960, W. Mackay in 1960, Peter Borthwick in 1962, then Bobby Bell from 1963 to 1966. Bell replaced the original 1098 cc engine with the 1220 cc unit currently in the car. Desmond Freere bought the car in 1966, and it was from Freere that the current owner, Dick Berger, purchased it.

Back in October 1958, Allan Ross, American restaurateur and skilled amateur driver wrote to Broadley to order a 1959 Mk1. Little did he know that when he raced that car at Elkhart Lake, standing on the sidelines was a young 16-year-old Dick Berger, who fell in love with the Mk1 and vowed one day he would own one. In 1968, Berger had left the U.S. armed services and went to England to fulfill his dream of owning a Mk1, never having forgotten Ross’s performance nine years earlier. He couldn’t find one at the right price, but on his return to the USA, spotted an ad in Autosport for the car being sold by Desmond Freere. After some months, the car was shipped to the States, though Berger didn’t discover it was the prototype until 1985. Berger raced it three times in the Midwest, but encountered a hay-bale in his last race, leading to a declaration by his wife that the car or she would go! The car subsequently went into storage until 1995. Berger then learned of Don Haldenby, who had restored and looked after the Mk1 owned and raced by Stirling Moss. In addition to looking after all of Moss’s racecars, Haldenby’s list of credentials also included time as an F1 mechanic for the BRP and Yeoman Credit teams from 1958-62.

Haldenby restored the car to its 1968 specs over a four-year period, with serious effort going into the deteriorated front and rear sections of the chassis. Rats and mice had also taken a toll on the wiring and the interior, however the bodywork remains in its original unpainted aluminum finish. When completed, Derek Bell raced the car at the first Goodwood Revival meeting in 1998. But the clutch couldn’t cope with the power from the 1220 cc Climax engine, which Bobby Bell installed in ’63/’64, and it expired. The following year the problem was solved, and Mark Hales drove the car to 6th overall at Goodwood. Berger himself still doesn’t plan to race it.

Driving the Lola Mk1

After Don Haldenby warmed up the brakes and checked the car out quickly over the lovely little one-mile impromptu circuit we had at our disposal, it was my turn to try the elegant-looking Lola. I got the potent Climax engine barking into life with a quick stab of the pedal, snicked first gear and was off on the first of several sentient laps in a racecar full of feel.

All of Broadley’s effort to build a car with the ability to make maximum use of the chassis in getting power to the road was abundantly evident. The car does whatever you want it to, and the lightness is so apparent that the relatively small engine seems much, much bigger. The Lola leans tidily into the first tight left -hander in third and the revs rise to 6000-6500-7000. The efficient little Sprite box allows an easy, close ratio change to fourth to run up a short straight, then hard onto the drum brakes (which never faded corner after corner). Then it was quickly down to third and immediately to second to take a very tight and decreasing radius left with full power in second, while sliding the rear out.

Photo: Ferret Fotographic

This is the first car I have ever driven in which it was apparent in less than a lap that all the work and steering would be done by the throttle. Good thing too… with a rather small and spindly steering wheel bending under duress! That Broadley understeer is evident in the medium speed bends, as the next faster left onto a wide straight demonstrated with the car running right out to the edge of the grass. Then up to top again and into another winding left through a narrow gap to go past our start area, the car totally steady and stable under braking and power application. Strangely, there was no buffeting in the wide cockpit, the well-thought-out screen and the shapely front doing a good job of sending the air over the car and not into the driver’s face.

Two, three, four, five, six laps and the torque of the Climax just pulled the little Lola around at quicker speeds, but with less effort, as it was easy to let the chassis do all the work. Even a high-speed avoidance of an errant learner driver failed to ruffle the car’s good track manners, and I was soon thinking about how nice this car would be, at say….Paul Ricard for the 12-Hour Historic race! What a great car, it’s no wonder it led to so many good things for Lola. It fully deserves its place in history as one of the best front-engine sports racers.

Buying and Owning a Lola Mk1

If you can find one, buy it!

The Mk1 now comes onto the market so rarely that when they do, they are expensive, the last one changing hands for 80,000 pounds…….that’s about $140,000. Yet, they are such competitive cars, and so good at beating the opposition in historic races that they will bring good prices. Once you have one, however, it is a straight-forward car to maintain, the Climax engine being thoroughly reliable, and the bulk of the mechanical parts being readily available. Of course, all this depends on your use, and serious racing will bring higher costs, but the rewards are high. Just ask Chris Phillip, who won the BRDC class championship in his.

And at something approaching $86,000, Dick Berger might be persuaded to part with the prototype. If you are interested, contact Don Haldenby.

Specifications

Year of Manufacture: 1958

Chassis: BR-O/ Lola Mk1 Prototype

Type: 2 seat, sports racer

Chassis Type: Tubular

Weight: 820 pounds with oil and water

Wheel-base: 86”

Track: 48” front and rear

Suspension: Front: Independent with coil springs, telescopic dampers. Rear: Rear wishbones with coil springs, telescopic dampers.

Engine Number: FWE4007526

Engine Type: Coventry Climax

Engine Capacity: 1220 cc

Power: 120BHP

Cylinders: 4

Head: 8 port, 2 valves per cylinder.

Carburetors: Weber DCOE 45, mechanical fuel pump

Lubrication System: Wet sump

Gearbox: Austin A30/35

Drive: Rear wheel drive by driveshaft

Brakes: Hydraulically operated drums

Brake Size: Front –10” x 2”; rear – 10” x 1.5”

Steering: Morris Minor rack and pinion

Wheels: Alloy, 15” x 4.5” front, 15” x 5.5” rear

Tires: Dunlop Racing 4.50 x 15 front, 5.00 x 15 rear

Resources

Lola Mk1

Hales, Mark

Autoweek, Jan.31, 07-31-2000

Lola’s First: The Definitive History of the Mark 1

Pratley, David

Bookmarque Publishing, 1999

ISBN- 1-870519-54-X

Don Haldenby

DCH Autocraft

Unit 13, Enterprise Park

Beck View Road

Beverly, Yorkshire, HU17 0JT UK

Tel 0482-871470