European Editor Ed McDonough recently became the first person outside Team Lotus to drive one of the best kept secrets ever created by Colin Chapman, the Lotus 58, or by its proper designation, the Type 57/58. Had Jim Clark not been killed at Hockenheim in April 1968, Lotus history might have been different – the 58’s radical wedge shape may well have meant wings didn’t get as much attention as they did – the future landscape of racing may have looked very different.

Colin Chapman, as is well known, was probably the greatest innovator in Grand Prix and all other single-seater racing. He had an unsurpassed knack for creating the future, as evidenced by his stunningly successful Formula One cars, the Lotus 25, 33, 49 and 72. As the 1967 season was winding to a close, Chapman was desperately trying to engineer a Lotus renaissance. Clark hadn’t won a Driver’s Championship since 1965, when Lotus also took the constructor’s crown. In 1966, Clark won only one race, and Lotus was a lowly 6th in the constructor’s points. The Cosworth DFV-powered Lotus 49 burst onto the scene in 1967 to replace the Climax-powered 33, and while Clark won 4 times he was to end up 3rd in the championship to Hulme and Brabham, with Lotus 2nd in the constructor’s race. The 49 still had some way to go.

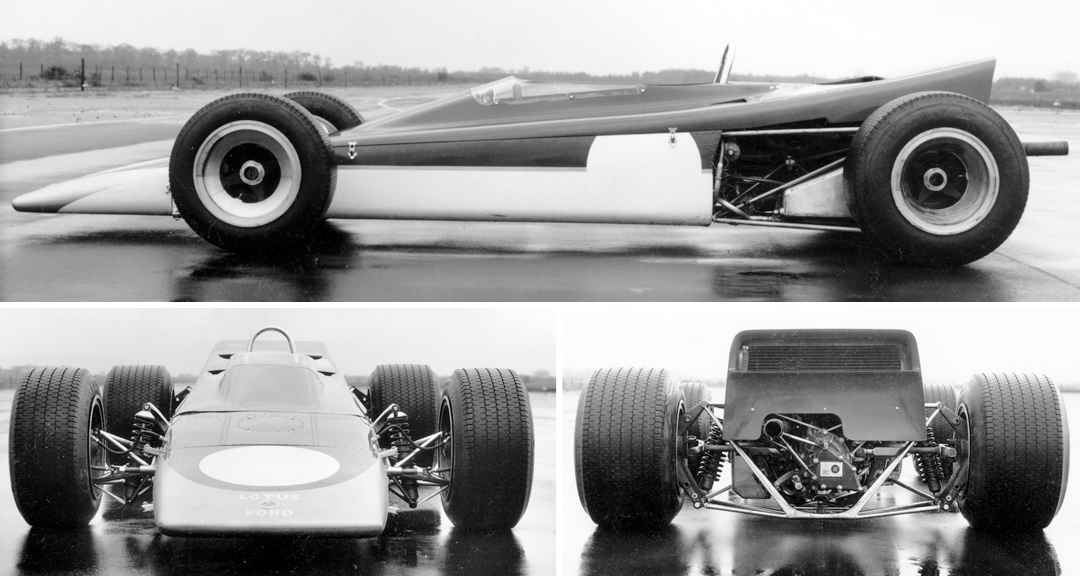

During this period, Chapman began playing around with an aspect of racecar design that had intrigued him, but hadn’t been developed successfully by anyone else. This was the combination of a full De Dion suspension system and a fully aerodynamic body. In secret, Chapman did the bulk of the design work while Martin Wade, from the drawing office, produced the final plans for a car which was fully intended to be the future of Lotus Grand Prix racing (assuming the De Dion concept could be made to work). The intention was for Clark to develop the car through 1968 in both F1 and F2 configurations, the Lotus 58, referring to the F2 car, and the 57, referring to what would become the F1 car.

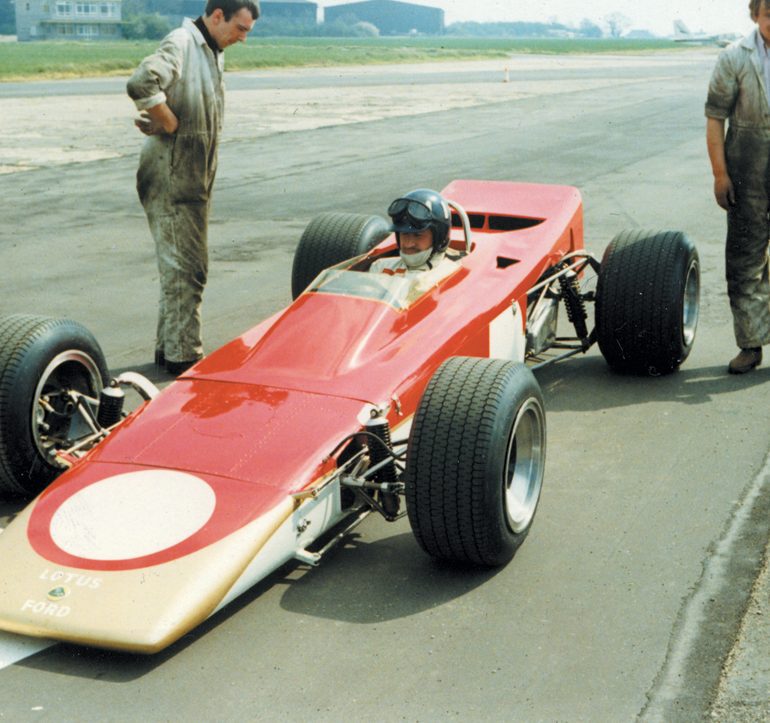

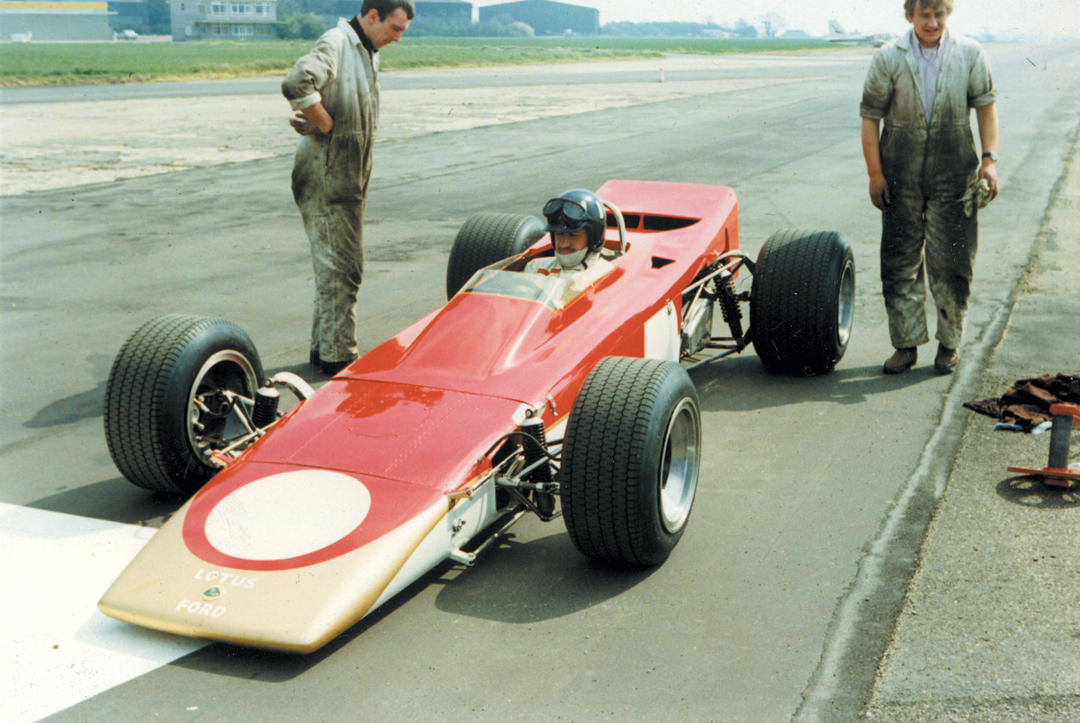

The Lotus 58, with a 1600 cc Cosworth four-cylinder FVA (which had been the mainstay of F2 in 1967), was finally completed at the beginning of April. On a Sunday morning Colin Chapman brought along his wife Hazel and his young son Clive, as well as Martin Wade and mechanics Dave Sims and Mike Gregory to watch Graham Hill give the car its maiden outing. A further test at Zandvoort was due to take place on the Monday after Clark was killed in a Lotus 48 F2 machine at Hockenheim.

Photo: Peter Collins

Mechanic Sims recently reflected on that initial outing 32 years ago:

“I remember being tired. We had done two allnighters to get the car finished because it had to run that Sunday morning, being there was nothing going round on the test track from the production side that day.

Graham was a little bit negative about it because of the very strange feeling of the wheels staying upright and the body rolling. I hope the potential of the car might come out now, because after Jimmy got killed, the old man put the wraps on it, and it didn’t do anymore miles until he wanted to put a 2.5-liter Tasman Cosworth DFW in it – which we did. It ran around Hethel again, but then it didn’t run anymore after that. It was never put to the test, which was a shame because Jimmy would have given a lot more input. It was going to be his car. It was made for him, and he was going to do a big program on it all that year, not racing it but testing it and developing it into an F1 chassis. It was a real shame.

Graham didn’t do a lot of running with it. It has a Mark 2 oil tank in it now, and on the first day it had a Mark 1, a smaller one, and on the right handers it would pour the oil out; so we had to come up with a plastic make-shift tank. We did some mods on it that night and came back for a couple more hours on Monday morning. Graham drove it again, having flown home to Elstree and then back. We solved the oil problem but he never got to grips with it. We only had one compound of tires and could have used something softer. It was just a shakedown. Graham wasn’t really impressed. I am really amazed to see it out again after all that heartache. It really was a significant car that unfortunately never ran.”

Chapman was devastated by Clark’s death, as was the entire team, and he nearly lost his heart for racing. The 58 had been a “Clark project,” and Chapman couldn’t bring himself to carry on with it, so it was put aside. It re-emerged later in the year with Tasman series mechanic Leo Wybrott charged with the responsibility of assessing whether a 2.5-liter Cosworth DFW (in what would be called the Lotus 57) would be a competitive package for the 1968 Tasman series in Australia and New Zealand. Wybrott did some laps in it in this format, and Michael Oliver in his book “Lotus 49-The story of a Legend”, reports that Graham Hill drove it again and was still unimpressed. Oliver quotes Wybrott as saying, “The car didn’t seem too bad to me… it seemed to go quite quick. You have to assume that, as we were young and wild, it probably was going quite quick but not from the viewpoint of a racing driver. Graham drove it for quite a time. It wasn’t just one or two laps to say it was a bucket of rubbish, he did persevere with it on the day.”

Photo: Peter Collins

I caught up with Leo Wybrott, who added a few more details to the hazy story of the 58. He recalled that it had been designed primarily as an F1 car, the dual-purpose notion had come later, and it had engine-mounting points for a DFV from the beginning. He also remembered that Hill drove it twice in Tasman form, and even after some modifications, the project was dropped.

Hill’s lack of enthusiasm, combined with the continued impact of Clark’s death and the fact that the complex Type 63 four-wheel drive car was progressing, saw the Type 57/58 pushed away for some 31 years.

The Restoration

The Lotus 58, or its chassis and separate components, seemed doomed to disappear. It was consigned to the redundant stores at the factory until another Lotus mechanic, Bob Dance, attempted to rescue it by moving it to Ketteringham Hall where some work was done on it by Dance with the blessing of then Team Lotus chief Peter Warr. There was limited time for the work, so the car was then put away in what was known as “the Piggeries” storage area, which at least meant it would be safe. It stayed there until 1998, during which time it caught the eye of Chapman’s son Clive and his Classic Team Lotus organization.

The Classic Team’s activity in historic Formula One sparked the interest of historic racers Malcolm Ricketts and Don Hands into convincing Clive Chapman that the car should be restored and run in the Historic F2 Championship. Ricketts had an engine and gearbox. Hands provided some funding, though it wasn’t difficult to get Clive interested recalling his presence as a schoolboy at that 1968 test where he was photographed sitting in the car.

Long-time Lotus race mechanic Eddie Dennis then spent some 1500 hours bringing the car back to its original Type 58 condition. Although the original drawings are all in the possession of Classic Team Lotus, a number of difficulties were encountered in sorting out the various changes which had taken place, and there were only a handful of photos ever taken of the car. VRJ recently got Eddie Dennis to talk about his experiences with the car, including the shakedown laps he had done a few days before the restored car was unveiled:

Photos: Peter Collins

“I did 7 or 8 laps on just half of the test track, and it was a little bit difficult. The distance between the corners seemed pretty short! It’s a quick little car, but the highest I got was 4th gear. The car felt quite nice…it’s all a bit of an unknown with the De Dion suspension, which requires a different technique for driving, and it was the first time I’ve driven an F2 car or a racing car, for that matter, in 20 years! The brakes didn’t fill you with confidence. The amount of leg effort is more than a modern day car. There’s a lot of learning to do.”

The car has several “novel” features, not necessarily unique by today’s standards, but still worthy of note considering when the car was designed. There is the De Dion suspension, a format that has been around since the 19th Century but rarely used in a racecar. This approach to suspension incorporates a rigid axle between the wheels, while the chassis is suspended from the axle, as contrasted to independent suspension where the chassis is suspended on each wheel. What Chapman had hoped to do was use the combination of this suspension and a high down-force body to deploy the reliable camber control of rigid axles and gain better tire performance. As tire specifications were changing so rapidly in the late 1960s, this had a major influence on chassis design. Tire development never advanced with this car, and while it is currently on Dunlop Racing 4.75/10.00 x 13 at the front and 6.00/12.00 x 13 at the rear, there is some uncertainty as to whether it had a “taller” tire in the original test to complement the suspension.

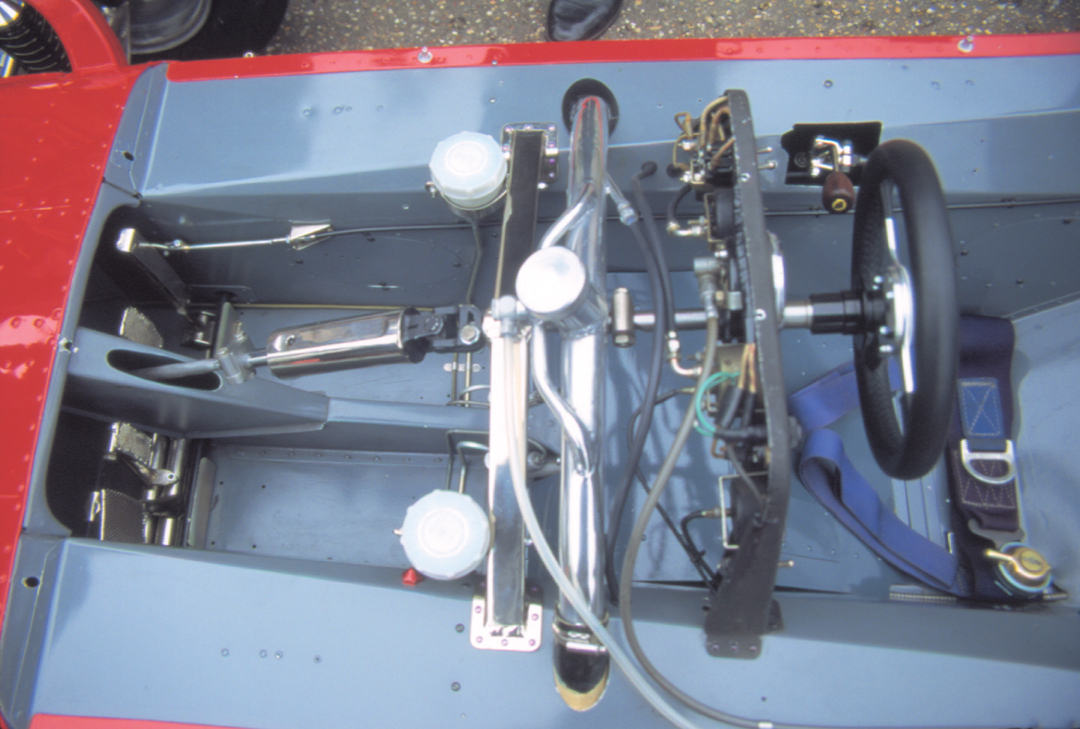

The other feature, and a bit of a shock when you are not expecting it, is the use of twin brake pedals, with a second brake to the left of the clutch. This was there to allow the driver to pump up the pressure on the straight and diminish braking effort and time on the way into and through a corner. Fortunately, I think, the extra pedal had been wired off for the time being as the car undergoes further development.

A closer look at the car reveals just how complex the suspension really is, with a detailed De Dion subframe, twin radius rods and coil spring and damper at the front, and single radius rods in combination with a subframe and coil/damper units in the rear. The Ford Cosworth FVA, a high revving engine with a narrow power band runs with Lucas fuel injection and produces some 225 bhp. The solid-looking aluminium monocoque is in fact quite light resulting in the car weighing in at only 950 pounds. Due to the car’s extremely light weight, braking force is supplied by relatively small 12” outboard disc brakes.

Eddie Dennis emphasized how the driver has to get used to the fairly dramatic difference of feel in this car, where the chassis can be seen to move rather than the wheels moving in a conventional modern racecar. Dennis also recalled how the “Old Man” had researched De Dion suspensions and how others had fared with this approach, but Chapman always insisted on building something himself to try it out and see if it would work.

Driving The Lotus 58

Photo: Classic Team Lotus

The launch of the restored Lotus 58 took place in front of Ketteringham Hall where Colin Chapman had his office and where the original Team Lotus was based. In the presence of the entire Chapman family, former Lotus F1 driver John Miles (who drove the 4-wheel drive Lotus 63), Lotus and BRM engineer/designer Tony Rudd and many ex and current Team Lotus staff, the dramatic wedge-shaped car emerged from its covers, surrounded by several other historically important Team cars.

Lunch was followed by the serious business of Don Hands and Malcolm Ricketts getting their first taste of the project they had nursed along so carefully. The entourage drove the few miles to the famed Hethel test track behind the Lotus factory, but a rain shower meant there was plenty of standing water, so Hands and Ricketts were very cautious with the car. The poor conditions meant that I had resigned myself to just watching when a very generous Clive Chapman, with the agreement of the project’s backers, asked if I wanted to “have a go” with this incredibly important racing Lotus.

So, there I sat suspended in a moment of racing history. Jim Clark was for me the greatest ever racing driver, at least the greatest I had ever seen, not having had a chance to watch Fangio. And here was Colin Chapman’s son Clive, and Jim Clark’s mechanic Eddie Dennis belting me into this resurrected time traveller. I had a hard time trying to maintain my concentration with all that buzzing around in my head.

The Lotus badge sat in front of my nose, adorning a three-spoke wheel, which had been made removable in the modern style. My hands gripped a wheel connected to a sliding spine steering column, which was necessary with the De Dion suspension. Though there is a wide monocoque chassis which is not crowded, the car is very low for its period, with the engine canted over by 11 degrees to reduce overall height. The rev counter sits on the simple racing dash just above the Lotus badge, with the oil and water gauges and starter button to the left, fuel pressure gauge and switch to the right.

Photo: Classic Team Lotus

The secondary brake had been wired off so it now functions as a foot rest…just as well. A large dividing member in the cockpit separates the clutch on the left from the brake and throttle on the right, so no left-foot braking is possible. The gear knob from the original car had gone missing and was replaced by a period one that Eddie Dennis found at home. Every bit of the car tells a story.

After both Hands and Ricketts did some warm-up laps, there was some concern about overheating due to the small rear-mounted radiators. There is a duct cut in the engine cover which was to accommodate the DFW, and the airflow for the FVA still needs some tidying as the cool air isn’t blowing back into the radiator. As I blipped the throttle for my run, there were last minute reminders to stay off the curbs, as the low ride height and the very vulnerable suspension means you absolutely must avoid obstructions! A few revs were required to get under way, and I was off onto the damp and twisty Hethel track, site of the development of so many famous Lotus racers. But there was no possibility of having the luxury of reflecting on this as everything had to go into keeping the car in one piece. There are no run-off areas at Hethel!

I was immediately impressed by the solid, reliable feel of the Hewland gearbox, with no tricky changes or popping out of gear. It’s been 27 years since I last had an FVA engine behind my head; and this one, out of a sports racing car, was behaving quite well, though the wet meant I wasn’t likely to see the top end of the power band! What becomes immediately apparent is that this car possesses a different type of handling; and in spite of considerable water on the circuit, I was getting the power down much earlier than I would have expected.

Each corner became a treat as the car decelerated with no fuss; there was the sensation of a slight movement forward, just evident as the suspension continually counter-balanced the chassis. The effect is a car which is totally stable, entering and accelerating from a corner, even with one rear wheel in a puddle. Is this what the four-wheel drive Type 56 felt like? Each time I passed the impromptu pit area, I could see a group of worried people huddled together. I began to use a few more revs, managed to quickly work up and down the box, tried some harder braking manoeuvres, but it all ended much too soon, and I never got to wander off into a Lotus-inspired fantasy and a race against the great Jim Clark. But I will watch the Lotus 58 in the Historic F2 Championship with a very special sense of involvement.

Photo: Peter Collins

Owning and Maintaining a Lotus 58

This is the only one and you can’t have it…Ricketts and Hands have worked too hard with Clive Chapman for that to happen. And you may be just as happy with that as Formula 2 cars are not easy machines to run. This is a car which has yet to have its development period. The March-BMWs of the 1980s back to the early Lotus, Ferrari and Brabham F2 cars were all machines which benefited from what happened in their F1 departments, and privateers had a hard job on their hands to keep them competitive. Formula 2 racing was always tough and always dangerous, so F2 cars are not to be taken on without serious consideration of all the issues. But if you were offered this car, could you resist? I couldn’t, and didn’t. Thanks, Clive….and Colin.

Specifications

Chassis: Aluminium monocoque.

Length: 159.5”

Width: 70”

Height: 31”

Wheel-base: 96”

Track: Front: 68.25”. Rear: 70”

Weight: 950 pounds

Engine: Ford Cosworth FVA 1600 cc.

Carburetion: Lucas fuel injection.

Horsepower: 225 BHP

Gearbox: 5-Speed Hewland FT-200-41

Bodywork: GFRP

Suspension: Front: De Dion subframe, twin radius rods, coil spring/damper. Rear: De Dion subframe, rear radius rods, coil spring/damper.

Brakes Front/Rear: 12” outboard solid disks.

Wheels: Front: 13” x 9”. Rear: 13” x 12”

Tires: Front: 4.75/10.00-13. Rear: 6.00/12.00-13

Resources

Lotus 49 – The Story of a Legend

Oliver, Michael

Veloce Publishing, 1999

ISBN- 1-901295-51-6/UPC

Classic Team Lotus

Clive Chapman

Ketteringham Hall

Hethel, Norfolk NR14 8EY

England

44 1603 810535 (Tel)

44 1603 810606 (Fax)

Other sources include original Team Lotus mechanics Dave Sims, Eddie Dennis and Leo Wybrott.