Pat Harrington-Johnson was a South African newspaperman who covered motoring and shipping for the Natal Mercury before and after World War II and he was involved in editing what was the most remarkable motoring magazine ever produced.

Harrington-Johnson was born in 1912 in the Forest of Deane where his father was the village curate. The family moved to South Africa in 1917 for the sake of his mother’s health because she suffered from acute asthma and it was hoped that the change to a warm climate would relieve the ailment.

According to his family, Pat had always been obsessed with all things mechanical so when he had completed his schooling he soon began modify motorcycles and then took part in trials riding.

When WWII broke out, he enlisted and became a dispatch rider. In order to join their unit in the north African western desert these riders travelled thousands of miles up through the vast continent on the army allocated motorcycles to Egypt.

Pat’s “war” was short lived. In late 1941, he was captured by the Axis forces at Sidi Rezegh, near Torbruk, when Field Marshall Rommel’s Panzer divisions overwhelmed the 5th South African infantry. Along with some 3 000 other prisoners he eventually ended up in the infamous Stalag IVB near Mühlberg-on-Elbe, some 30 miles north of Dresden where along with other Allied troops they were incarcerated under dreadful conditions. The trip from Torbruk in north Africa to Stalag IVB was a harrowing experience in itself, with the POWs being marched huge distances through the desert before being shipped to Italy and then to Germany.

The infamous ‘IVB’ had been designed to hold 15,000 prisoners but at times up to 30,000 men were crammed into “filthy, cold wooden huts which were vermin infested.”

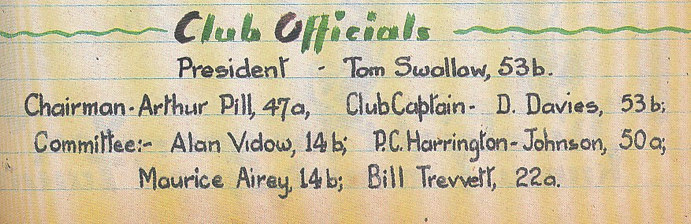

In an attempt to raise morale and relieve boredom for incarcerated men who had “nothing to do and nowhere to go”, Pat’s lifelong friend Tom Swallow, a dedicated motoring enthusiast, gathered together a group of fellow inmates and established the “Mühlburg Motor Club” in a bid to “find work for idle minds.” The ‘club’ soon had over 200 members who met when possible to talk about cars and motorcycles.

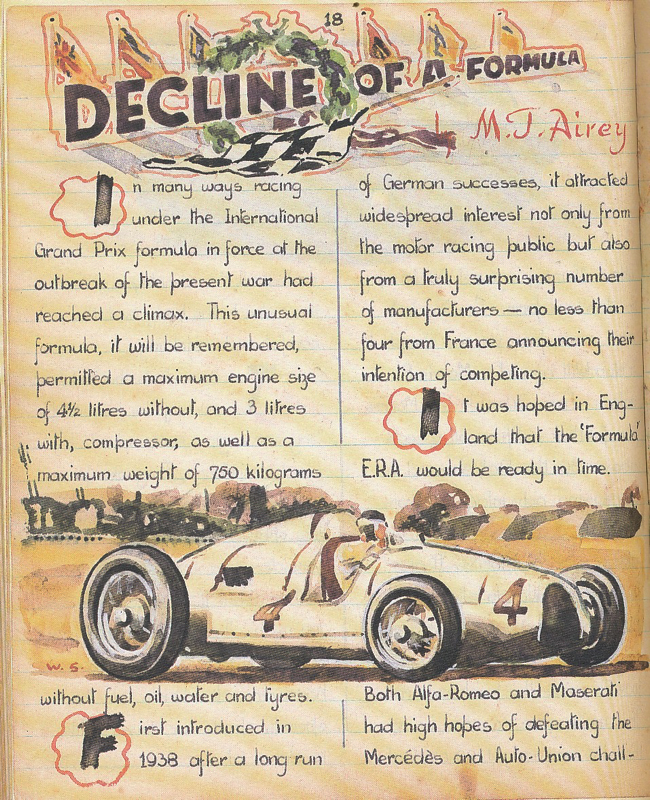

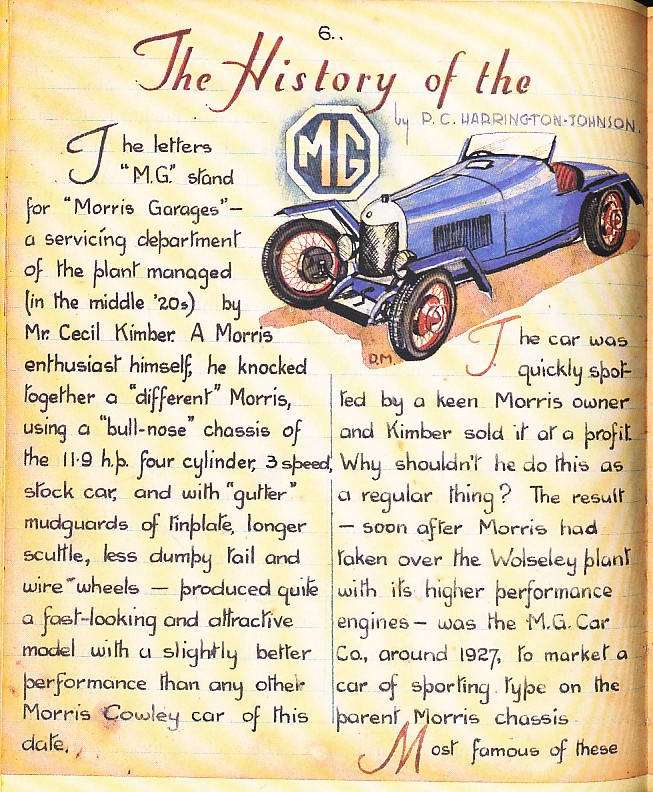

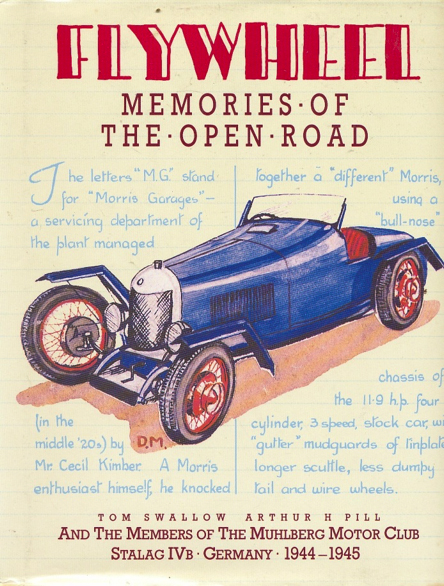

As a project Swallow decided to publish a motoring magazine and Pat, because of his journalistic talents and motoring experience, was elected as editor and he is credited with dreaming up the name The Flywheel for the new “magazine.”

“Stealth was the name of the game,” Harrington-Johnson recalled. “We collected all the exercise books we could find and spread the word around to all the chaps who had a motoring yarn to tell so they could contribute. Ink was something we most certainly didn’t have – but of ingenuity we had lots!”

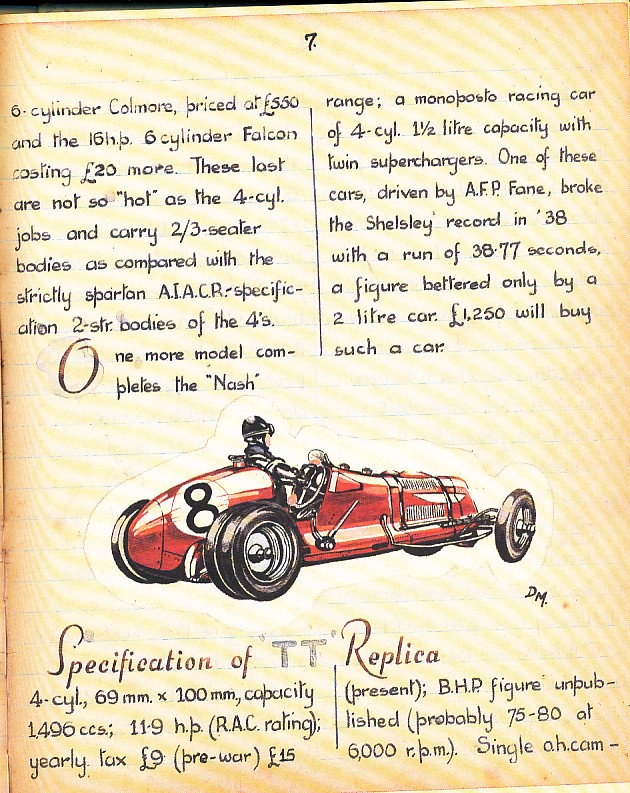

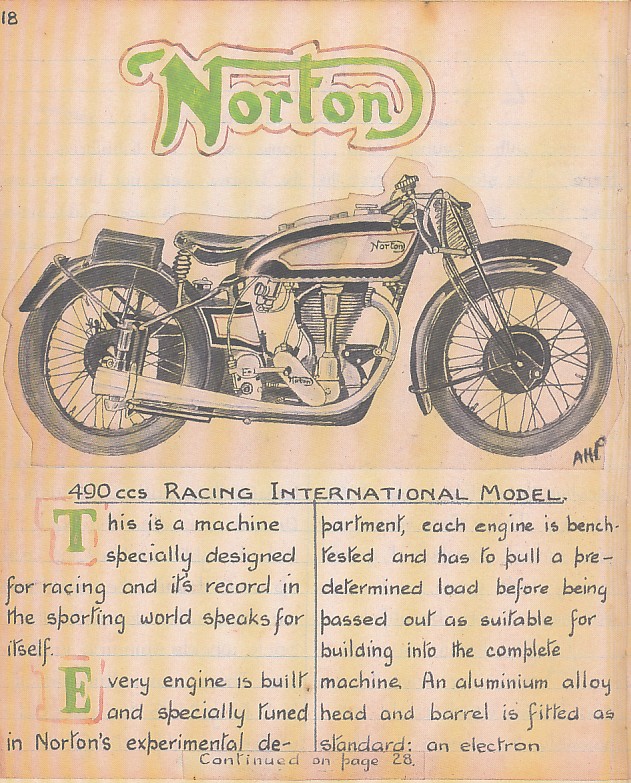

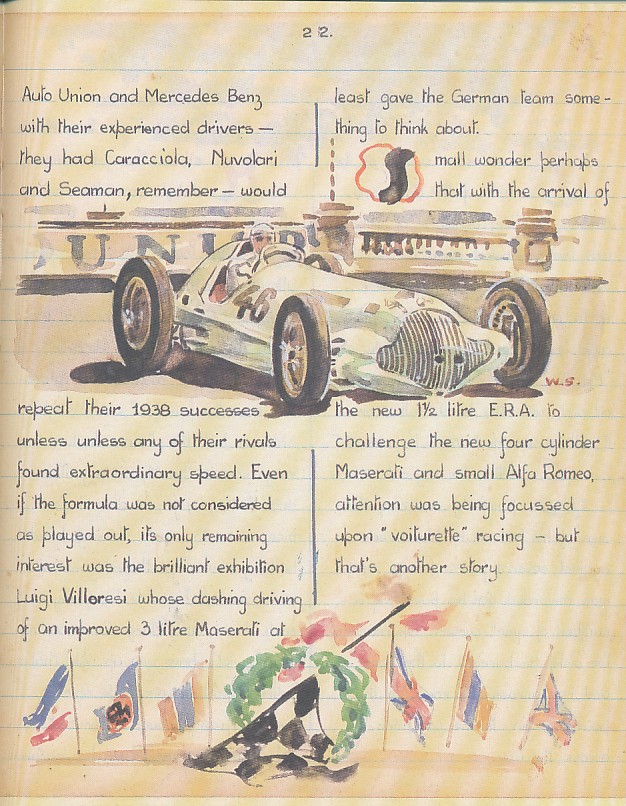

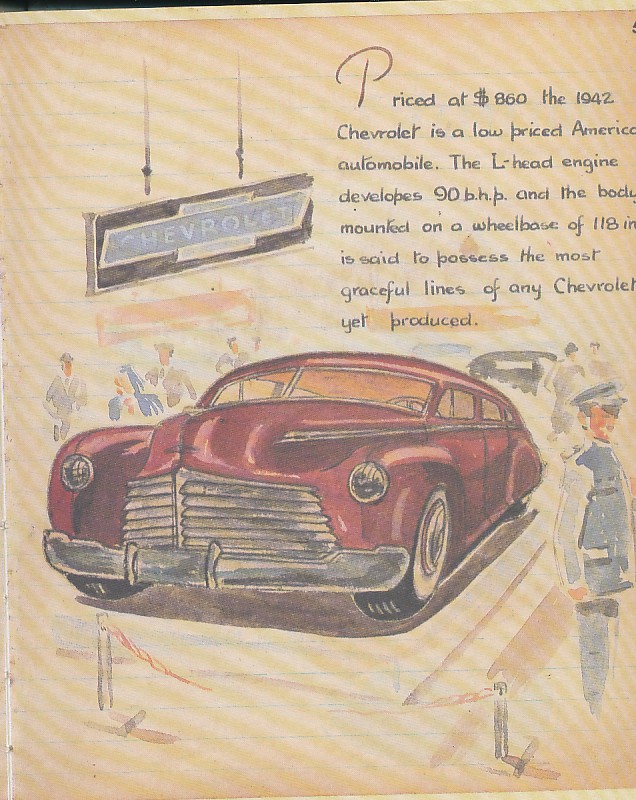

Fellow inmate Tom Rodger handwrote every page and illustrations were beautifully colored in with inks the inmates produced from pilfered materials which included quinine tablets. The illustrations were affixed to the exercise book pages using fermented millet soup.

The effort of concentration to handscript the journal with rudimentary equipment in cramped conditions in a hut occupied by 200 men is difficult to comprehend but the finished product looked almost as if it had been professionally printed.

The illustrators were truly gifted. Motoring books or magazines were not available in the camp so Bill Stobbs and Dudley Mumford and others produced illustration after illustration of motoring and motorcycling entirely from memory!

“Issue No 1” was a huge success, and the circulation manager played a key role, for there was but one hand lettered and illustrated edition of each issue, so it was his task to bring it to each of some 200 readers circulating it from hut to hut and collecting it later.

Although great care was taken to preserve the “magazine” in as best condition as possible through constant use and page turning some damage was inevitable.

It is hard to imagine how, with such limited resources available (and working only from memory) the men in the camp could collaborate with their POW mates to produce such detail. Intricate drawings of models and parts that they actually had not personally seen for 3 or 4 years were lovingly reproduced by hand, under extremely difficult circumstances. Moreover, they were obsessed with getting every article correct too, and would redraw items until they knew these were as accurate as possible.

Flywheel No 11 was in the throes of production in March 1945, when fighting closed on Mulberg with the Russian army and U.S. military advancing. But just when the POWs thought they were free, as the war ended, the camp was taken by Cossacks of the First Ukrainian Army, who simply replaced the German guards who had fled and kept the anxious inmates confined for a further six weeks!

When the only available food – potatoes – ran out, the prisoners were marched some 30 miles to Riesa where they were eventually liberated by American troops. Harrington-Johnson and his fellows were flown to Britain from where they were returned to South Africa.

Pat then resumed work at the Natal Mercury and began touting the merits of the new 500 formula in his motoring column. Meanwhile, the innovative 36-year old started to build a racing car. His ideas stemmed from discussions with fellow inmates while a POW and from the Iota magazine that gave guidance to those interested in building the little motorcycle-engined racing cars.

While many amateur motor restorers and builders work in the evenings, after a day at work, Pat worked in the day in his garage at home after a night at work – because the Mercury being a morning newspaper required he worked at night.

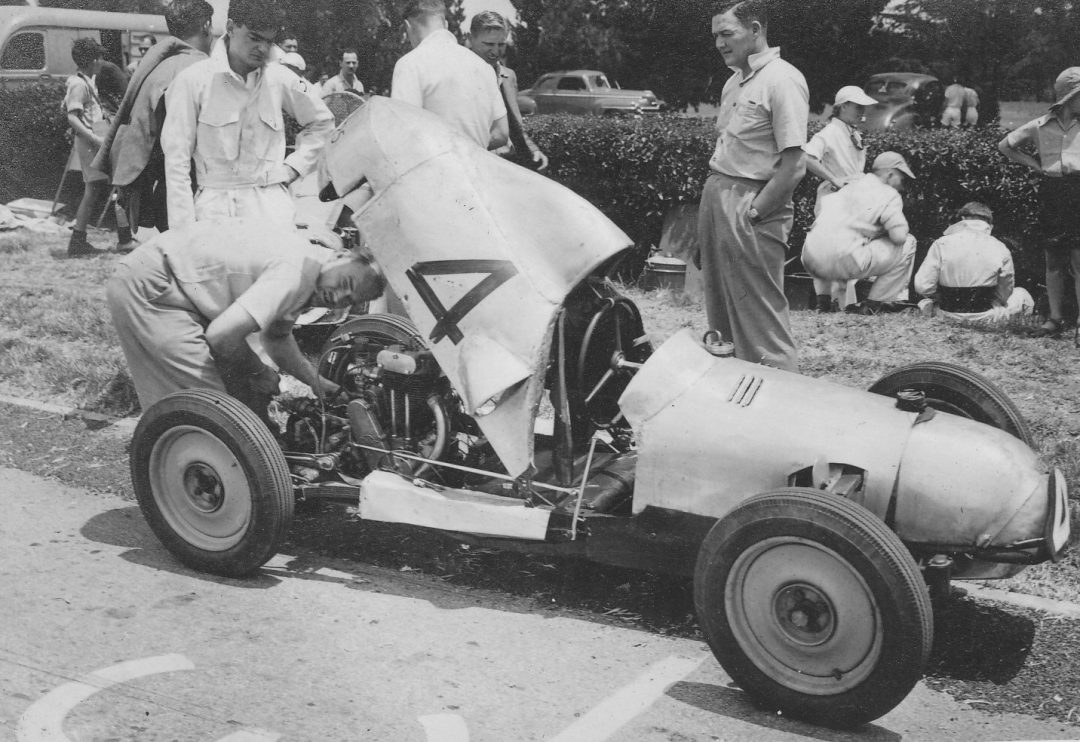

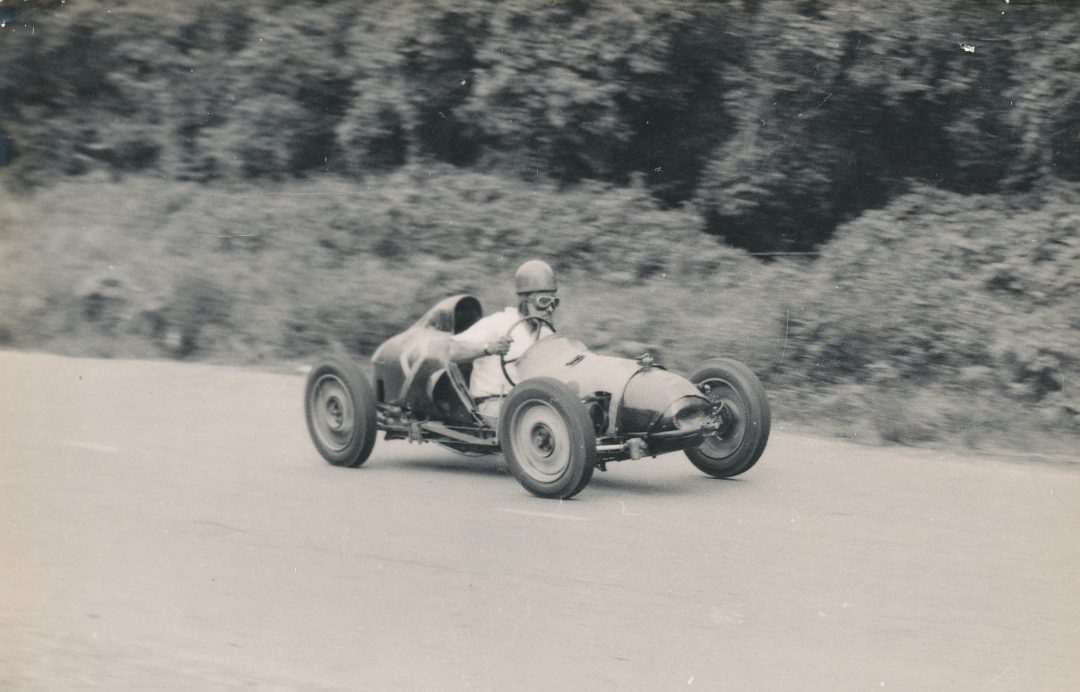

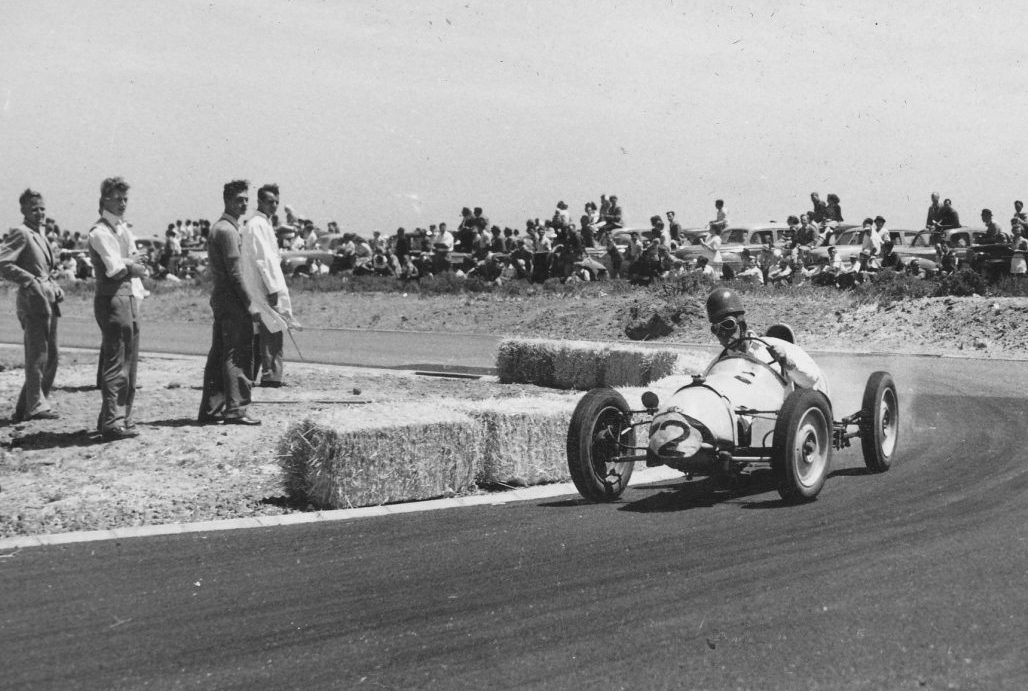

The “Fidget” was entirely a backyard, garage-built and entailed regular visits to the local scrapyards and ‘friends’ at the local engineering shops. A 1937 Fiat Cub chassis was chopped and lightened to form the basis for the special that was named after his nickname.

His engine selection, a single-cylinder 500 Matchless G/8L was based on affordability and availability and, despite producing only some 21 horsepower, showed a good turn of speed together with impressive handling.

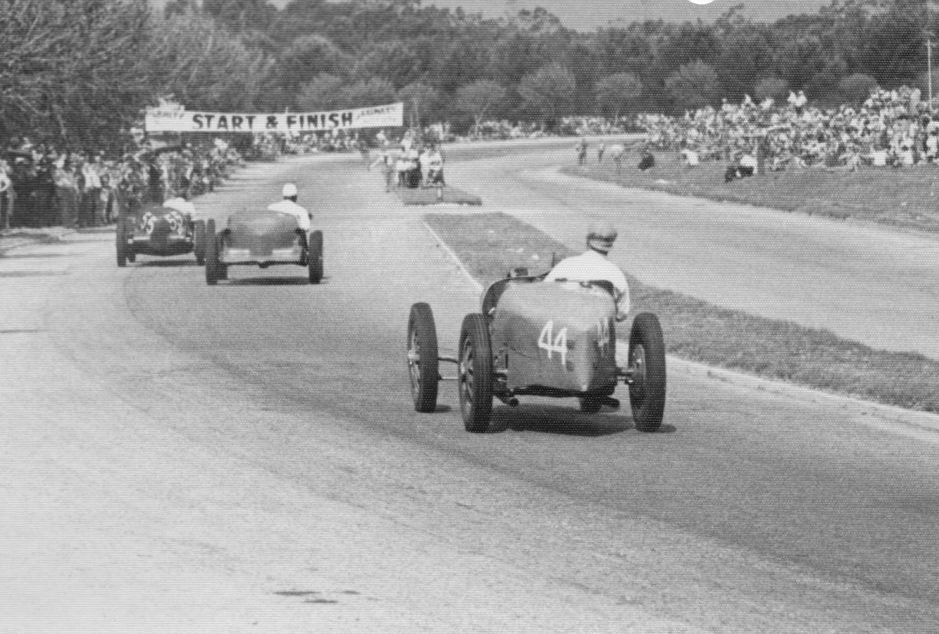

So, in October 1948, “PC” Harrington-Johnson was one of the first drivers to race a 500 motorcycle-engined racing car in a South African event, when he drove his self-built creation in the St John Crusader Handicap on a track using the public roads around the Germiston airport.

While his tiny rear-engine ‘cyclecar’ with its roaring motor failed to finish the race, the unusual machine caused quite a stir amongst the large field of factory-built pre-war racing machines such as an ERA, Maseratis and Talbot sports cars and the variety of homebuilt and ‘cut down’ specials.

In fact, racing was eventually stopped at this circuit due to cars crashing into the crowds.

The Fidget competed in races from late 1948 to early 1952 and at times Pat and his car travelled over 1000 miles by train or ship to compete in events at far flung venues such as Cape Town and Johannesburg. Although the Fidget became one of the more competitive junior cars in the early 1950s it was beset with gremlins and dogged with unreliability and chalked up a number of DNFs, resulting in Pat describing it as a “beastly” thing.

However, the benefits of a good power-to-weight ratio were more evident in hillclimbs. The Fidget had the 1948 Burman Drive Hillclimb ‘in its pocket’ until it spluttered to a halt near the finish with a piece of darning wool blocking its petrol pipe! Then at the Sydenham Hillclimb, Pat set third fastest time of the day against a large field of larger-engined cars and, in 1950, he set a record run at Burman for the up to 850-cc class.

However, the Fidget would eventually be outclassed by the racing JAP and Norton engines that were fitted to the imported Coopers and Harrington-Johnson, now with a young family, retired from his racing pursuits.

Copies of The Flywheel miraculously survived all of this drama and in 1987 were the basis of a limited edition book titled Flywheel – Memories of the Open Road which reproduced many pages from the original publications.

The Flywheel must surely be the most remarkable motor magazine ever produced and fortunately many of the original works have been preserved and are on display in the Imperial War Museum in London.

“Pat was ahead of his time – he had an unbelievably thorough encyclopedia of knowledge about any motor vehicle manufactured between 1910 and 1960” says a contemporary. He also built a folding sidecar which he raced, a trials motorcycle and equipped a car with controls for disabled people.

Pat passed away in 1988.