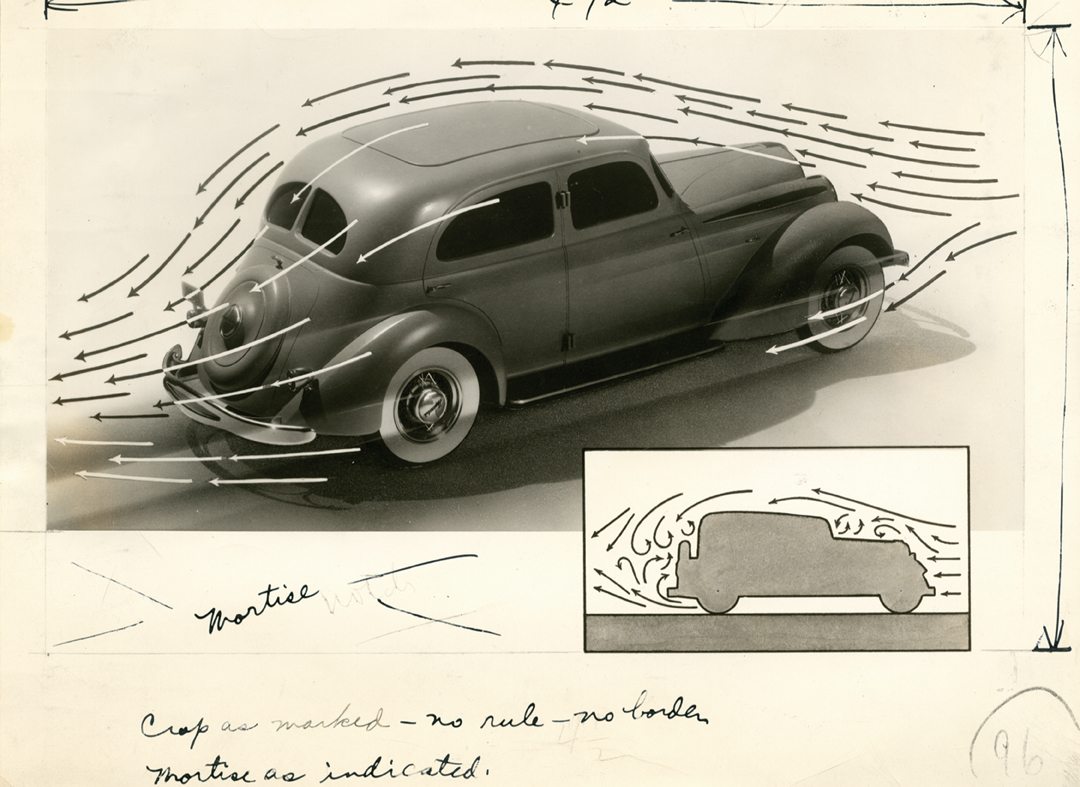

The livescience.com website defines aerodynamics as “the study of how gases interact with moving bodies. Because the gas that we encounter most is air, aerodynamics is primarily concerned with the forces of drag and lift, which are caused by air passing over and around solid bodies.” Airplanes were the catalyst that brought serious focus to aerodynamics. To make them fly, a designer had to understand how air passed over and around them. It wasn’t long before designers were looking at how to apply aerodynamics to other moving bodies —cars and trains—and even some static designs affected by wind, e.g. buildings and bridges.

Early Automobile Aerodynamics

Once past the motorized buggy stage of automobile development, designers looked for ways to improve vehicle speed, stability, economy, comfort, engine cooling and performance, as well as ways to entice buyers to their products. Early on, finding the ultimate shape for a vehicle depended on how well the designer could visualize how the air flowed over it.

They were influenced by the knowledge of how a drop of water is shaped as it falls through air—thus, the “teardrop” was potentially seen as the ultimate shape for automobiles. The appropriateness of the teardrop shape was a strongly held belief even into the 1930s when automobile aerodynamic styling had become more aesthetic than scientific. In his 1932 book, Horizons, industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes said, “An object is streamlined when its exterior surface is so designed that upon passing through a fluid such as water or air the objects created the least disturbance in the fluid in the form of eddies or partial vacua tending to produce resistance.… An object is streamlined in order to eliminate disturbances in the media through with it passes.… It is my prediction that within the next two or three years some farseeing manufacturer will again turn his attention to making his machine go, that this time his design will be the result of what has been learned in this motorized buggy era. This means that he will start afresh and that his objective will be the ultimate form of the future motor car. This car will look very different from those you see on the road today but not very different from Car Number 8 (a very teardrop-shaped car). It will take the public about two years to accept the idea, but they will do it for the simple reason that the basis for it is right.… The consuming mass has imagination and admiration. They like the new idea that is better than the old one and they idolize the fellow who blazed the way for it.” Geddes was not alone in his opinion about the ultimate shape for an automobile, but he and the other proponents were wrong about that shape being the ultimate. Ultimately, the most efficient shape is not always the shape that provides the most comfort for the people inside.

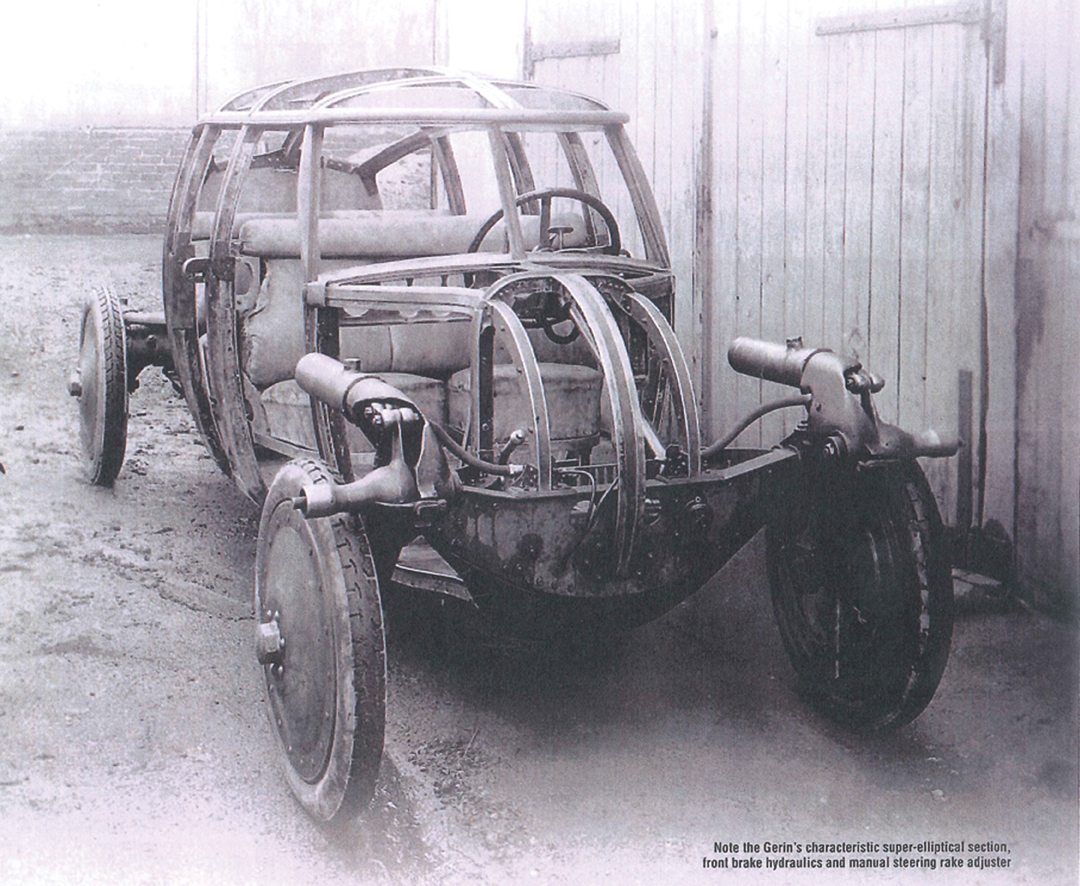

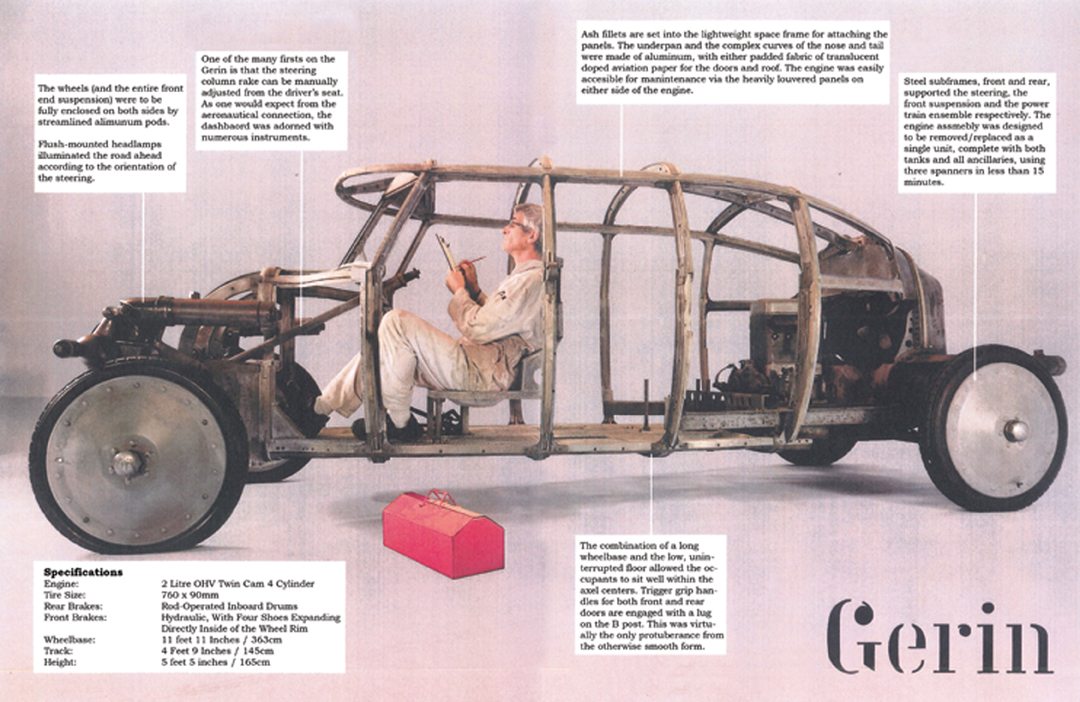

The Italian coachbuilder Castagna built an early teardrop-shaped 40/60 hp A.L.F.A. for Count Ricotti in 1914. It was actually slower than the standard car on which it was based. With the engine located in the passenger compartment, ventilation was also a problem. There were many attempts to produce an automobile with an aerodynamically efficient shape that also provided for occupants, but most of them failed. In 1922 aeronautical engineer Jacques Gerin used Duraluminum for the spaceframe chassis on his Gerin Aerodyne. It was to be a light, teardrop-shaped streamliner for the French public. Although it never received a body, Gerin drove it an estimated 5,500 miles but was unable to generate sufficient interest in the concept to enter into production. The Claveau of 1926 was an angular attempt at a teardrop shape, but by 1931 the company had moved to a more contemporary look with the wheels moved inside the bodywork. Edmund Rumpler created a rear-engined concept that looked like a thick, vertical wing. Like many others, it was an intuitive design based solely on his aircraft experience. It was ugly and had a coefficient of drag of 0.54—much higher than most modern cars. Other examples of prototypes that failed to energize the public included the Martin Aerodynamic Car, a one-off built for General Billy Mitchell by the Martin Aircraft Company, and the McQuay-Norris Streamliner, of which six were built.

The Importance of Paul Jaray

Paul Jaray was probably the most influential proponent of automobile aerodynamics. Jaray was born in Vienna, Austria, of Hungarian descent. He became the chief design engineer for the German Luftshiffbau Zeppelin, where he designed the airship Bodensee, the teardrop design of which became the basic design for the company’s other airships, including the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg. While at Zeppelin, he conducted some experiments in the company’s wind tunnel and developed streamlining concepts for automobile design. His idea was that all parts of the body should taper horizontally and/or vertically to an edge at the rear of the car, similar to his airship design. After leaving Zeppelin in 1923, Jaray formed two companies—Streamline Carriage Body Company in Switzerland and Jaray Streamline Corporation in the United States. He designed his own car, the Ley, which achieved a coefficient of drag of 0.29, remarkable for the time. That got the attention of other designers. He had already been awarded patents for his automobile shape in both Germany and the U.S., so he was able to license the design to major manufacturers. Some, like Tatra, obtained a license; others, such as Chrysler and Pierce Arrow did not. Jaray sued Chrysler over the Airflow and Pierce Arrow for the Silver Arrow. He was awarded a small amount along with the promise of royalties from the sales of both cars. Unfortunately, neither did well.

Jaray-style bodies appeared on a number of automobiles—Opel, Audi, Mercedes-Benz, Maybach and Adler, in addition to the Airflow and Silver Arrow, but it was Hans Ledwinka at Tatra who most closely applied Jaray’s principles to the cars he designed. The Tatra T87 and T97 are still probably the best examples of the Jaray body shape, and possibly the most successful.

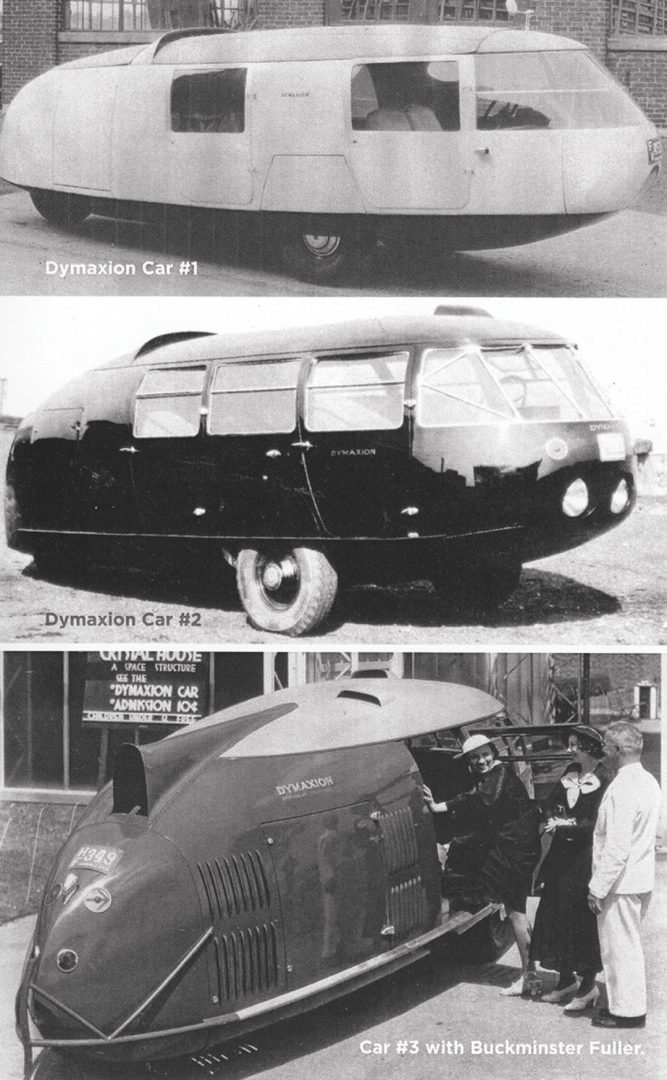

Bucky Fuller’s Dymaxion Car

The teardrop shape preceded Jaray’s designs, but, if looked at through squinted eyes, it still fits the shape he described. It was a shape R. Buckminster Fuller, like Geddes, believed could be sold to the American automobile buying public. It had to be someone like Fuller who would build and attempt to market a car like his Dymaxion—the most aerodynamically crafted automobile ever built. He was a renaissance man; known as an architect, engineer, cartographer, mathematician, poet, sailor, philosopher and inventor. Mostly, however, he was a thinker.

Fuller was born in Milton, Massachusetts, in 1895. His early education was at the Milton Academy, after which he entered Harvard in 1913 and again in 1915. Apparently, Fuller liked to socialize and wasn’t particularly concerned with exams, resulting in two dismissals from the school. During WWI he served in the Navy, where he designed a winch for rescue boats that allowed the quick removal of downed airplanes. Recognizing his engineering abilities, the Navy sent him to the Naval Academy to receive officer training. By 1919, Fuller had risen to Navy Lieutenant. He left the Navy at the end of the war and had a variety of jobs leading up to working in his father-in-law’s construction company, where they developed and patented a new method of producing reinforced concrete structures. It was Fuller’s first patent; he would earn a total of 25.

Unfortunately, the construction company failed in 1927, leaving Fuller unemployed and with time to consider his future. He realized that he had an ability to study problems and develop solutions, and he decided to apply that ability to improving life through technology. His design philosophy became “doing more with less,” a philosophy that led to the Dymaxion House, a mass-produced house that could be air lifted to its final location; Dymaxion Deployment Units were mass-produced shelters based on circular grain bins; and the geodesic dome. The geodesic dome was a wonderful example of “doing more with less.” It used its external structure to balance the compression and tension forces in the structure, eliminating the need for internal supports and maximizing the usable space inside the structure. A geodesic dome built for Expo 67, Montreal’s 1967 World’s Fair, is still on display there.

But it was Fuller’s adventure with automobile design, with the Dymaxion car, that is of interest here. The word Dymaxion, a contraction of dynamic, maximum and tension, was first used for his Dymaxion House. Originally called the 4D House, managers at the store where a model was displayed created “Dymaxion,” which they believed to be better than 4D in their advertisements, and it was used for many of Fuller’s subsequent creations, including his car.

Fuller’s original concept was for a car that could fly and float. His idea was to revolutionize how people travelled. In an article in a 1987 issue of Automobile Quarterly, Fuller is quoted as having written: “I decided to try to develop an omni-medium transport vehicle to function in the sky, on negotiable terrain, or on water—to be securely landable anywhere, like an eagle.” The flying-floating part would have to wait until suitably light materials and powerful engines were developed, but in the meantime, it was to be an economical and fast automobile capable of transporting up to 11 people at a claimed top speed of 120 mph, while getting 30 mpg. The story of how the Dymaxion car came to be is easy to follow, although many of the details vary depending on the source of the information. Jeff Lane, of the Lane Motor Museum, spent a year researching Fuller and his car before having a replica built, so the results of his research will be used to determine which of the details is most likely correct.

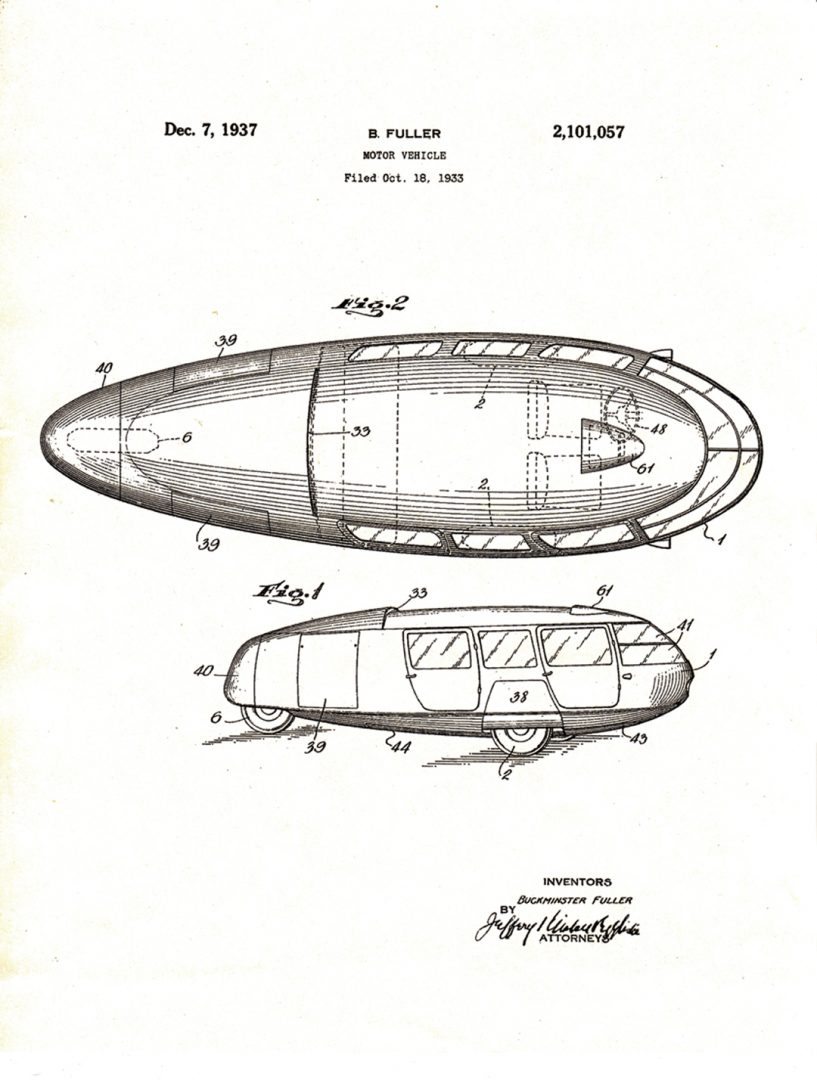

It was 1933 when Fuller decided to pursue his concept for the ultimate aerodynamic automobile. He convinced friend and socialite Anna Biddle to finance building the car. He rented a building in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and hired a staff of 27. Fuller had developed his concept, but it needed some detail work on the shape, so he had Isamu Naguchi make clay models for wind tunnel tests to finalize the shape of the fully streamlined body. Renowned yacht builder Starling Burgess managed construction of the automobile.

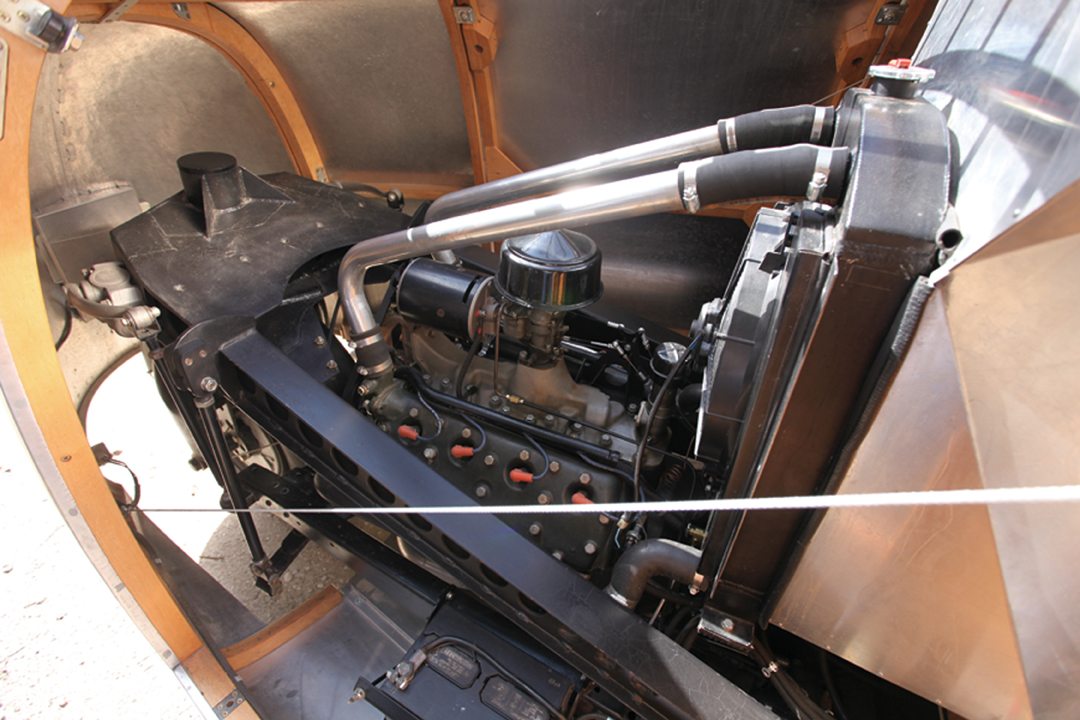

The Dymaxion car was a 19.5-feet long, three-wheeler with fixed front wheels and rear-wheel steering. The body was aluminum with chrome-molybdenum steel used for the chassis. It was powered by an 85 hp Ford flathead V8 mounted ahead of the rear wheel and driving the front wheels. The engine was mounted backward so that the driveline went forward to a standard Ford rear axle turned upside-down and mounted at the front. It had a three-speed transmission that was operated by a long shift rod. The rear wheel could turn 90° in the first two cars, so they were able to make a U-turn in their own length. There was even a unique three-frame chassis. The rear frame supported the rear wheel and was hinge-and-spring connected to the middle frame. That middle frame supported the engine and driveshaft, and was hinge-supported by the front wheels. The body had an independent frame sprung directly from the front axle with a balancing spring connected back to the middle frame. This arrangement supposedly resulted in a smooth ride, even over rough ground.

The body was formed over a beautifully crafted wood framework. The interior space was huge—378 cubic feet—with much of it finished in wood. It could easily carry the 11 passengers Fuller wanted. It was light and got the fuel economy he wanted, but his estimate of 120 mph was probably mentioned for effect—the car was clocked at 90 mph, but unless the gearing was significantly changed, 120 would not have been possible. Rearward vision was a problem too, so the cars used either a roof mounted mirror or a periscope—there were no side mirrors.

Three cars were built, each costing about $7,500 at the time—or about $130,000 in today’s economy. They all used the same basic design, but each had differences in details. Fuller did not want to be a manufacturer. He was an idea man, and he hoped to find an enthusiastic backer who, after seeing his cars, would take his idea and put it into mass production under license. He intended to show the cars at the Chicago World’s Fair, Century of Progress, of 1933–’34. His plan was not unique; four other manufacturers brought new designs to the Fair, hoping to attract new customers to their products in a rough economy. The cars were the “Golden Packard,” named because many of the interior parts were gold plated; Pierce “Silver Arrow,” possibly the most innovative of the four; “World’s Fair Cadillac,” which became the V16 Aero Coupe in production; and Duesenberg “Twenty Grand,” named for its listed selling price. The World’s Fair provided an excellent opportunity for promotion, something at which Fuller was good.

Car #1 was completed in July 1933, only four months after Fuller had rented the building. It was sold to Al Williams of the Gulf Refining Company. The car had no doors on the driver’s side of the car, and none of the windows opened. For ventilation, a canvas top was created so that it could be unsnapped and rolled back, allowing some air to get into the car. On October 27, 1933, the car was involved in an accident on its way to the World’s Fair. Two of the three occupants of the car were killed. The cause of the accident has never been determined, but one story was that it had been involved in a street race with another car or that the other car was chasing it to get a better look, resulting in a two-car crash that left the Dymaxion car overturned in a ditch. The car’s wood and canvas roof did little to protect the occupants. Unfortunately, the newspaper stories of the accident suggested that the accident was caused by the car’s instability. The result was that potential investors became reluctant to put money in Fuller’s project. The car was repaired and returned to its owner, where it was used in company promotions for a time. Eventually, it went to the U.S. Bureau of Standards, where it was destroyed in a fire in a Bureau garage.

Car #2 had been pre-sold to London businessman Fred Taylor, who wanted to be the agent for the cars in the United Kingdom. The accident involving car #1 caused Taylor to change his mind before the car was completed in January 1934. Fuller kept the car and used it as a demonstrator. That car also had an accident with Fuller driving and with his wife and daughter on board. The car overturned, but no one was seriously injured. That car was sold to a group of mechanics, then disappeared for years. A story of it having been used as a chicken coop seems not to be true, but it was in bad enough shape when it was found that it could have been used to house chickens. It made its way into casino mogul Bill Harrah’s collection and is now on display at the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada.

that it was approved. Sadly, his company had folded by then.

Car #3 was commissioned in January 1934 by Evangeline Stokowska, wife of composer Leopold Stokowski. After it was completed, it was displayed at the World’s Fair for a month before it was delivered to its new owner. The Stokowskis only kept the car less than a year before selling it. The car is known to have changed hands a number of times before it disappeared. It is believed that the car was scrapped during the 1950s.

With no more orders and out of money, Fuller closed his business in 1935. The patent he had submitted in 1933 for his design of the Dymaxion car was finally approved in December 1937, much too late for his business. He did have one more automotive adventure, this at the request of Henry Kaiser. In 1943, he redesigned the Dymaxion car as a five-seater with an air-cooled, horizontally-opposed engine on each of the three wheels. It never went past the design phase.

Time magazine included the Dymaxion car in their article “The 50 Worst Cars of All Time” in 2007. They were not at all kind to Fuller in that article, but they missed the impact Fuller’s car had on modern automotive design. Many of today’s cars are quite aerodynamic, and fuel economy, which was not a critical factor in the ’30s, is very important today and is increased in part because of aerodynamic design.

The Replicas

There is only one original Dymaxion car. To see it in person, a visit to the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada is necessary, but two people who were fascinated with the car have built replicas that might be seen at shows or even on the road, in one case. Several years ago, Lord Norman Foster created what he called Dymaxion car #4 in England. It is based on car #3, but has enough differences that he says it is not an exact replica. Now, Jeff Lane’s replica of car #1 is finished and has already taken to the roads on a maiden 600-mile trip.

Lord Foster was intrigued with the Dymaxion car #2 when he saw it at a show and decided to replicate one of Fuller’s cars. He chose car #3. He had worked together with Fuller on several projects during the last 12 years of Fuller’s life, and was impressed with the man, as well as with the car he developed. Foster took two years to create his car #4. In his research, he looked at more than 2,000 photos, but the key to his effort was borrowing car #2 from the National Automobile Museum. In return for the loan, he restored the interior of car #2 as best as could be determined from the limited information available. Foster has shown the car, but his Dymaxion remains in a private collection in England. Some will have the pleasure of seeing it, but it is not likely that it will spend a lot of time on the road.

Lane, on the other hand, intends to have his Dymaxion on the road whenever possible. When asked why he spent a year researching the car and eight years having it built, he said it was because it is a significant and rare automobile, and he wanted people to have the opportunity to see it. The car fits nicely into Lane’s collection—he likes unusual and significant automobiles. It is unusual enough that the New York Times and MSN have both done recent pieces on the car.

Lane’s Dymaxion is a replica of car #1, but with some changes for reasons of safety. The car has hydraulic brakes rather than the original cable-operated system, steering is also hydraulic instead of a system of chains, cables and pulleys, it has turn signals so it can be driven on the street, and side mirrors were added, although they are removed for shows like the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, where the car was shown for the first time in March 2015. The change to hydraulic steering reduced the turns lock-to-lock from the original 21 to 6, still quite a challenge for the average driver. Since there are no windows that open on car #1, hand signals can’t be used when turning, meaning that turn signals were needed.

Lane was able to find copies of about 60 drawings from the three cars, although they did not cover an entire car. The interior, for example, had to be created from the few photographs that were taken inside the car. Lane explained, “There were a couple shots going forward, so we could kind-of see the dash. There’s a shot going backward, so you can kind-of see the back.” He and his crew went to Reno and measured car #2 at the museum. The goal was to have it as original as possible, but even with photos, drawings and measurements, some of what was built was based on speculation.

Once the research was done and the plans developed, Lane turned to a friend in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, to build the running chassis. Bob Griffith and Chuck Savitske built the frames, engine, and drivetrain in their shop, and then sent it to the museum in Nashville where chassis testing was conducted. The chassis then went to the Czech Republic where Mirko Hrazdira built the wooden framework for the body.

Lane had used Hrazdira several years ago to build two replicas of the 1919 Layat Helico propeller car (Vintage Roadcar, January 2014) and respected his abilities. Lane saw pictures of the finished framework and called it “a work of art.” He added, “I hated to skin it with aluminum and hide most of the beauty of the body.” Once the framework was done, though, the car went to ECCORA, also in the Czech Republic, where Vitezslav Hinner created the aluminum skin, built the interior and finished the car.

The car arrived at the museum in Nashville in December 2014, where it went through a break-in period for both the car and Lane. In March, true to his word about putting the car on the road, Lane and three passengers drove it the 600 miles from the museum to Amelia

Island, Florida. When asked if they had any adventures on the trip, Lane enthusiastically replied, “We had lots of adventures, but overall the car went really well. The car ran good! We had a slight overheating problem one day, but really no other issues. We did about 200 miles a day; we took all back roads—no interstates—(and) travelled at 40 to 45 depending on the conditions. You go through all these places (you don’t normally see). Yesterday, in South Georgia, we stopped at a gas station where they take cash only. It was like these guys were back in time. People have never seen it, but they come running over to look at it because it’s so weird. We had a photographer from Hagerty with us, so we found some neat spots in Dawson, Georgia—in front of the courthouse, then we backed it into this old workshop—a car repair shop that looked like it probably did 50 years ago. It was hard to get the shots because people kept coming over to it. People loved it; the reactions where always very positive.”

Driving Impressions

Lane picked me up at the Ritz Carlton, headquarters for the concours, and drove us to Fort Clinch State Park at the north end of the island. With rear-wheel-steering and the amount of attention the car draws, I was happy to have him negotiate the traffic on road between the hotel and the park. At the park entrance, we were waved through. Lane asked if we needed to pay, but they recognized that he had been there earlier in the day and no additional fee was needed. I climbed behind the wheel, and climb is an appropriate verb, since there is no door on the driver’s side of the car. You sit tall in the seat with the large steering wheel and the few gauges directly ahead. The shifter is long, and the throw into the unsynchronized first is also quite long. At first, I couldn’t seem to get it to engage, then I remember that Lane appeared to use quite a bit of force to get it in gear. That’s what is needed to move nearly 19 feet of shift rod to engage the gears in the transmission. Once that is understood, shifting is routine for a transmission of that era. We were on paved roads in the park, so the ride was quite nice, and it didn’t deteriorate when we turned onto the sand roads where we chose to do the photo shoot. Turning a car with rear-wheel steering does require some thought. First, you want to have a light touch on the steering wheel so you don’t move it and get the tail wagging. A light touch will also help when the rear wheel hits a pothole or bump—overcorrecting is a bad idea. Finally, you have to remember to straighten the car a bit early when you turn a corner, since the rear end will swing into the oncoming lane if you wait too long. The car is quite manageable at low speeds, but it is unusual enough that Lane gets a lot of credit for driving it 600 miles. Bottom line—it was a lot of fun to drive such an unusual automobile. You couldn’t help but smile at the reactions of the people you passed, although most of the time you were biting your lip a bit and concentrating on not screwing up a car that took eight years to hand build!

Two storage compartments were included in the wood framing beside each of the rear seats.

When we arrived at the spot for photos, I experienced what the Hagerty photographer had during the trip. There weren’t that many people in the park, but they all seemed to flock to us. They came by in twos and threes, on foot or bicycle, and they all stopped to look at the car and ask questions. Lane is very patient and polite, although I had to ask people to move a little farther back so their reflection wasn’t in the glass or their bicycle wasn’t in the photo. This is a very popular car.

On the way back, I rode in the back, and I have to say it was not comfortable. I am not sure I could have done 600 miles back there. The rear seats are low, so your legs are out in front of you, and there is little to brace your feet on. I realized that fitting 11 people in the car would make it very tight, but if Lane would offer me a seat on his next road trip with his Dymaxion car, I’d have to say yes—and I’d do it with a smile. He’s planning more road trips. Watch for announcements—this is a car you need to see to appreciate what went into building it.

A thousand thanks to Jeff Lane for having such an incredible automobile built and for sharing it with so many people, especially me.

Specifications

Body: Aluminum over ash wood frame

Chassis: Three chassis system – chrome molybdenum aircraft steel

Length: 19.5 feet

Weight: 3500 pounds

Engine: Ford 85hp flathead V8 mounted backward in the rear, driving the front wheels

Bore/Stroke: 3.06 inches/3.75 inches

Transmission: Ford 3-speed at the rear of the automobile

Differential: Ford rear axle mounted upside down at the front of the automobile

Brakes: Cable operated (original); hydraulic (replica)

Steering: Rear wheel steering by chain, cable and pulley system (original); hydraulic (replica)

Interior: 378 cubic feet

attracted quite a bit of attention, maybe even more than the cars that won Best of Show.