There was a time not too long ago that a V10 engine in a supercar was nothing of note. It has only really been in the 2010s, with the arrival of performance hybrids and full EV hypercars, that manufacturers have started to follow the trend that the computer industry has since it started, that of smaller, more powerful, and more efficient. In other words, twin-turbo V6s are now becoming the supercar engine, especially when paired with a one or two electric motors, while only a few manufacturers still even whisper the word V12, and a few are steadfast in using V10s.

It is the latter that we’re looking at today, as they are becoming a rare breed of engine indeed. In fact, they are now so rare in the supercar field that it actually causes a stir when a company boldly claims “we put a V10 in there!”

Why V10s Are Disappearing, Despite Their Advantages

Yes, we used the big A-word in the heading there, as a lot of people say that V10s are, by their nature, difficult to make and work with. While there is some truth with that, if it’s designed and engineered well, as you will soon see, a V10 can be a properly epic engine.

The first major advantage with a V10 is that if you find the correct angle between the cylinder banks, the engine naturally balances itself out. No balance shafts, no counterbalancing ballast, just the reciprocating mass of the crankshaft and cylinders reaching a harmonic equilibrium and the engine is smooth as butter. For most V10s, that bank angle is 72 degrees.

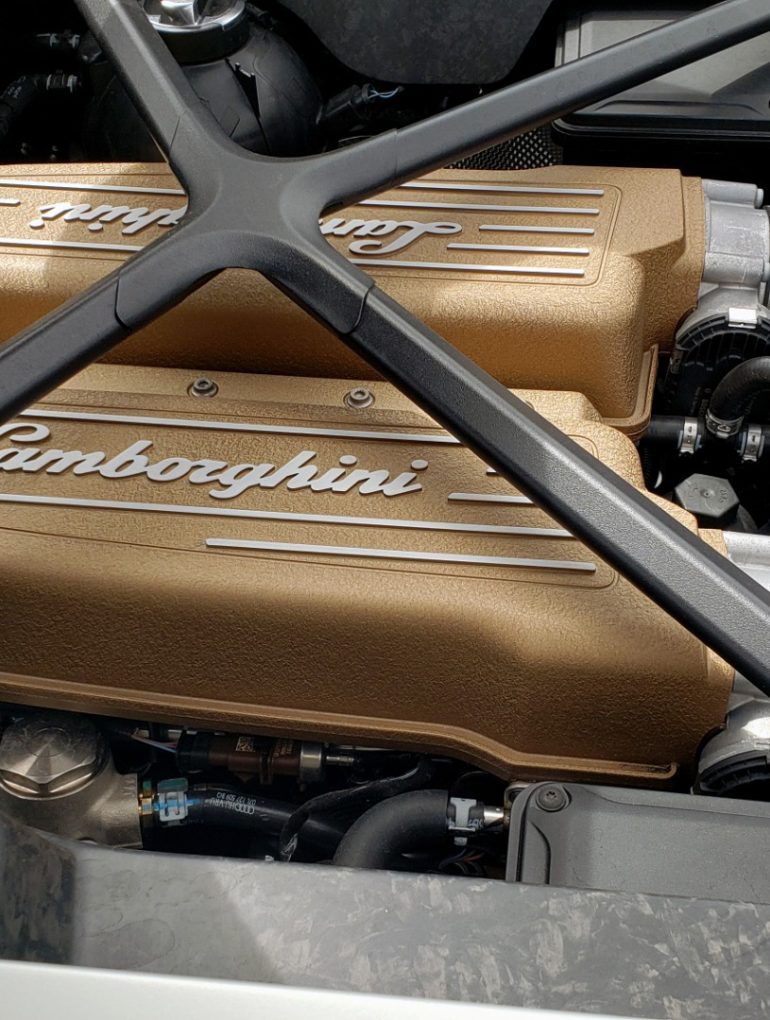

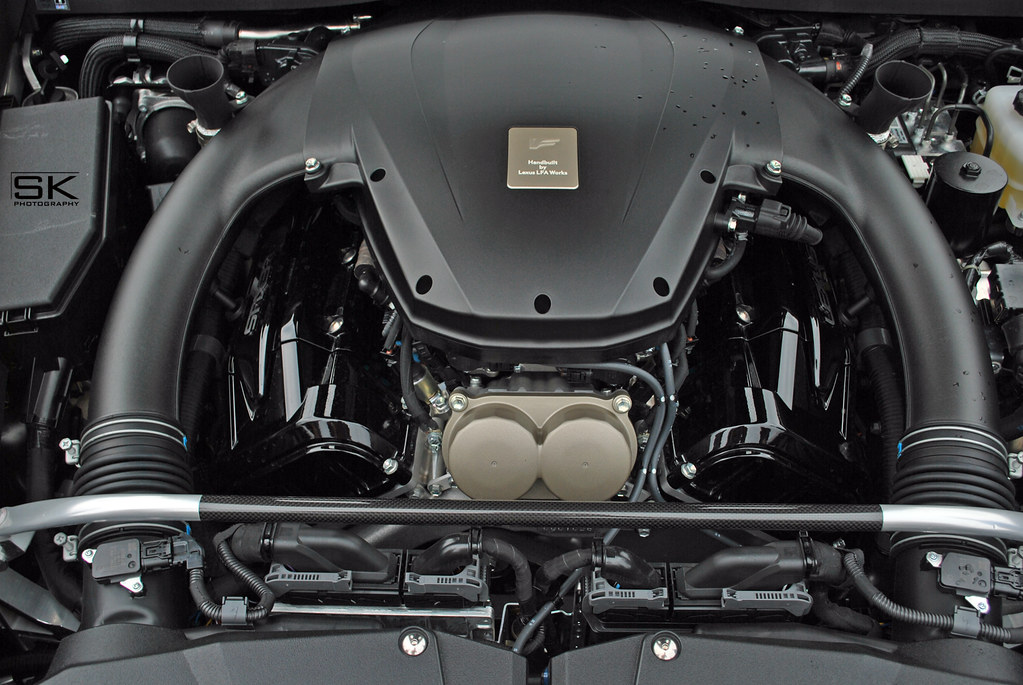

This is exemplified in one of the most glorious V10s to ever be put in a supercar, the Lexus 1LR-GUE in the superb Lexus LFA. It has a bank angle of 72 degrees, a bore and stroke of 88 and 79 mm respectively, and uses an even-firing order, meaning that its ignition goes L1-R1-L5-R5 and so on, between the left and right banks. Because of its design as a naturally balanced engine, as well as being relatively small displacement at 4.8L, it can rev incredibly fast without any type of vibration damage, from idle to its redline of 9,000 RPM in under a second.

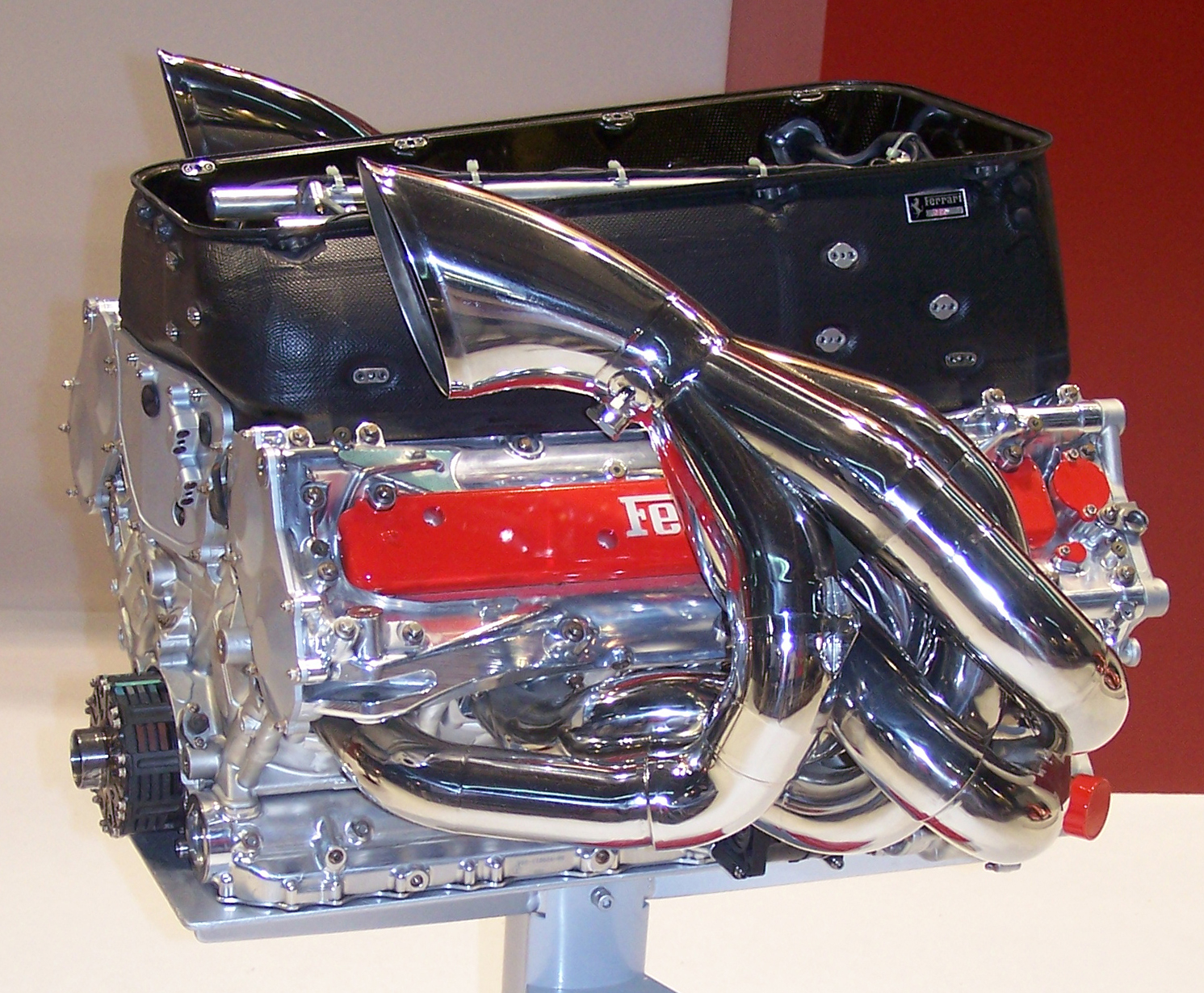

The second major advantage of a V10 is that it can produce some pretty incredible power. While V10s had been around for a while by the time the 1990s rolled around, there was a significant jump in the power and performance of these engines when turbocharged engines were banned in Formula One. V10s became the engine of choice 7 years after the turbo ban, so that every car on the grid in 1996 was running one, and they lasted until 2006, with some of the best exhaust notes to grace a grand prix circuit.

The reasoning is that despite being absolutely tiny at 3.0L, these naturally aspirated V10s had such precise balance and tolerances that by the time the mid-2000s rolled around, each cylinder was reaching 150 ignitions, or 300 full strokes, per second. That’s 19,000 RPM, and they were effectively chucking out 1,000 HP, naturally aspirated. While that is not something that would work for a road car, a lot of the technology and control systems for those engines did make it into road cars, a perfect example being the 2006-2010 BMW E60 M5. That car had the engine control, the engine itself, and the 7-speed semi-automatic transmission developed in conjunction with the Sauber F1 team, whom BMW were title partners with in the 2000s as BMW-Sauber.

While these are only two examples of why V10s are quite incredible engines, the fact of the matter is that while they produce incredible power and are astoundingly smooth if designed well, they are also very complex to make. We’re not talking in terms of pure assembly and mechanical items here, we’re meaning that if a V10 is not designed well, additional items such as balancing shafts, counterweight ballast, even a different profile of crankshaft are needed. These add two things a lot of manufacturers don’t want: weight and money.

Also consider that while you can put forced induction onto a V10, and get some insane results as demonstrated by twin-turbo Lamborghini Huracans out there with over 1,600 or more HP, it is much, much easier to do forced induction on fewer cylinders. A very common type of inexpensive performance car is the “Hot hatch,” which is generally a small hatchback with a turbocharged inline-four, and if you mate two inline-fours at the crankshaft and put them at a 90 degree angle, you have a twin-turbo V8 engine. They are inexpensive, produce immense power, and are lighter and shorter than V10s.

That last point is one of the biggest reasons that V10s are disappearing from not just supercars, but almost all cars. By the nature of needing 5 cylinders per bank instead of 4 or even 3, the engine is longer and heavier, requiring more chassis and body to cover the engine bay, be it front mounted or mid-mounted. With some properly skilled designers, you can make that work, an example being the perfect proportions of an Audi R8 or the angry, angular, attacking look of a Lamborghini Huracan, both cars sharing the same engine.

The final reason that they are disappearing is also one of the biggest generational shifts in not just engines, but motoring in general. We are living in the age of the usable electric car, something we will touch on later, but with less and less reliance on the internal combustion engine as the primary and only source of vehicular motivation, a V10 has turned more and more into an expensive risk that a manufacturer must consider when designing their next performance car. The results, as can be seen right now, are that they are choosing to go to twin-turbo V6s and naturally aspirated V8s more often than not.

There Are Only Two V10 Supercars Right Now

To highlight that the V10 is a very rare breed these days, only two supercars in 2023 can be bought new with 10 cylinders in them. The truly ironic part of this is that both cars share the same engine, the 5.2L FSI V10 from Audi, used in the Audi R8 GT and the Lamborghini Huracan. Both cars produce the same 550 to 650 HP, depending on the application and what version of the car you buy, and both share about 75% of components.

All other manufacturers are either doing V6s and V8s, or, if you’re looking more towards the hypercar and luxury end of things, V12s, W12s, and W16s. As stated at the beginning, it used to be that every other month you’d hear about a new supercar with a V10 engine, and over the past 20 years, those engines have slowly but surely stopped being made. You know it’s serious when even luxury road cars, like executive sedans from Germany, and luxury yachts like Bentleys and Rolls-Royces, have foregone the smooth-as-butter V10 to put in a V8.

The simple fact of the matter is that the V10, when done right, is an absolute powerhouse engine. Unfortunately, the last time a truly new, revolutionary, high-tech V10 made it in a supercar was the aforementioned Lexus LFA. That car was also a very special exercise in engineering and design, the “Billion dollar failure” of Toyota because they wanted to show what they could do if there were no limits on their engineers and designers. It is one of the most glorious supercars ever made, but it also bears the banner of being the last truly new V10 to make it to the road.

“But the Huracan came out after the LFA!” we hear you saying, so allow us to explain. The V10 used in the Huracan is an evolution of the V10 used in the original R8 V10 and the Lamborghini Gallardo, whereas the 1LR-GUE was a totally new, never before seen, never seen since V10 that had Formula One engineers involved, from when Toyota had an F1 team. They brought in Yamaha, makers of musical instruments and precisely balanced sportbike engines, to help develop and tune the engine, both figuratively and literally (there’s a reason it sounds so amazing).

So What Happens Now?

That… is a very loaded question.

At this point in time, performance cars are going through a massive shift in both thinking and motivation. Just over 30 years ago, the thought of a twin-turbo V6 engine in a supercar was laughable, and led to one of the “disaster cars” of the 1990s, the Jaguar XJ220. It was a disaster because no one wanted any less than 8 cylinders, and most wanted 10 or more.

Fast forward to today, and one of the most hyped and talked about supercars has a twin-turbo V6 in the middle paired with some electric motors. The Ferrari 296 is already widely accepted, lusted after, backordered for over a year, and has been hailed as one of the “best of the new breed.” The McLaren Artura is in a similar space, although it is desired more by the technically oriented than those looking for the latest prancing horse, as it is a twin-turbo V6 with a performance hybrid system.

There is also the fact that a lot of performance car, supercar, and hypercar manufacturers are all part of the unofficial “Green Promise,” the stated objective of which is to produce 80% or more of their total model lineup as either fully electric vehicles, or have electric versions of their cars, no later than 2030 to 2035. Porsche is already there with the Taycan, the upcoming Macan EV, and the upcoming Cayman and Boxster e-Performance cars. Audi is leading the charge, as they are aiming to have fully half of their models as EVs no later than 2027, and be completely electric, with the rare exception of a performance hybrid here or there, by 2030.

Perhaps the question should not be “Where have the V10s gone?” Perhaps it should be “In 10 years, will supercars even have internal combustion engines?” But that… that is another article entirely.