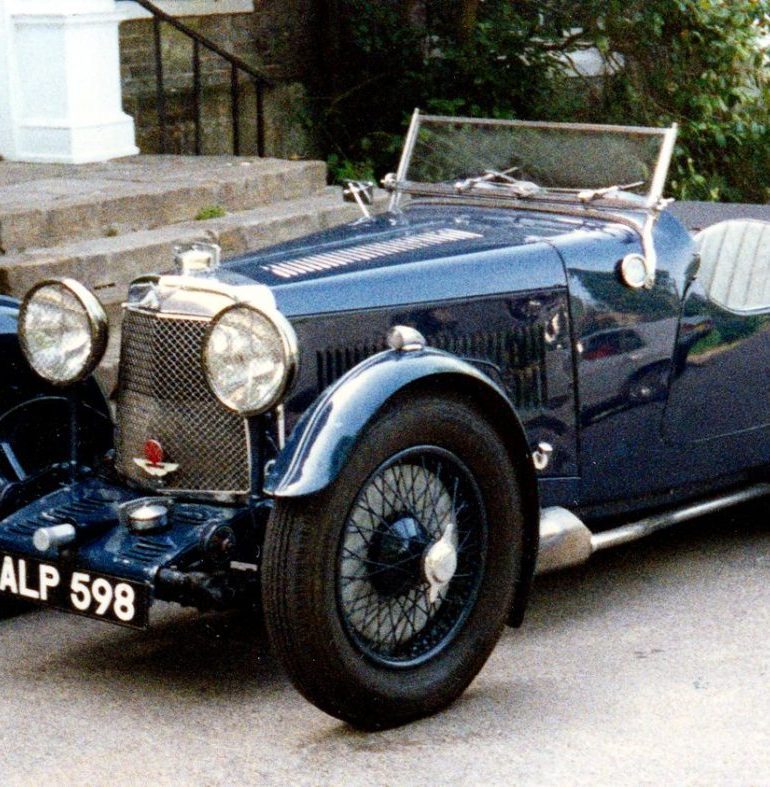

Before the ad offering it for sale was published in February 1982, ALP 598 was mine. “One of the prettiest of all the famous Le Mans cars,” it was called, “in superb restored condition. Finished in Prussian Blue with grey hide upholstery and black weather equipment.” That’s the way Coys of Kensington described this Aston Martin before I fell in love with it.

It was a case of love at first sight. One Saturday morning in December, I’d dropped a friend off in London’s Chelsea and, on the spur of the moment, decided to drive back through the warrens of ancient mews south of Kensington Gardens and west of Queens Gate because I knew purveyors of vintage motor vehicles infested these regions. My idea was to see what they were offering—out of curiosity. How innocently we embark on these journeys!

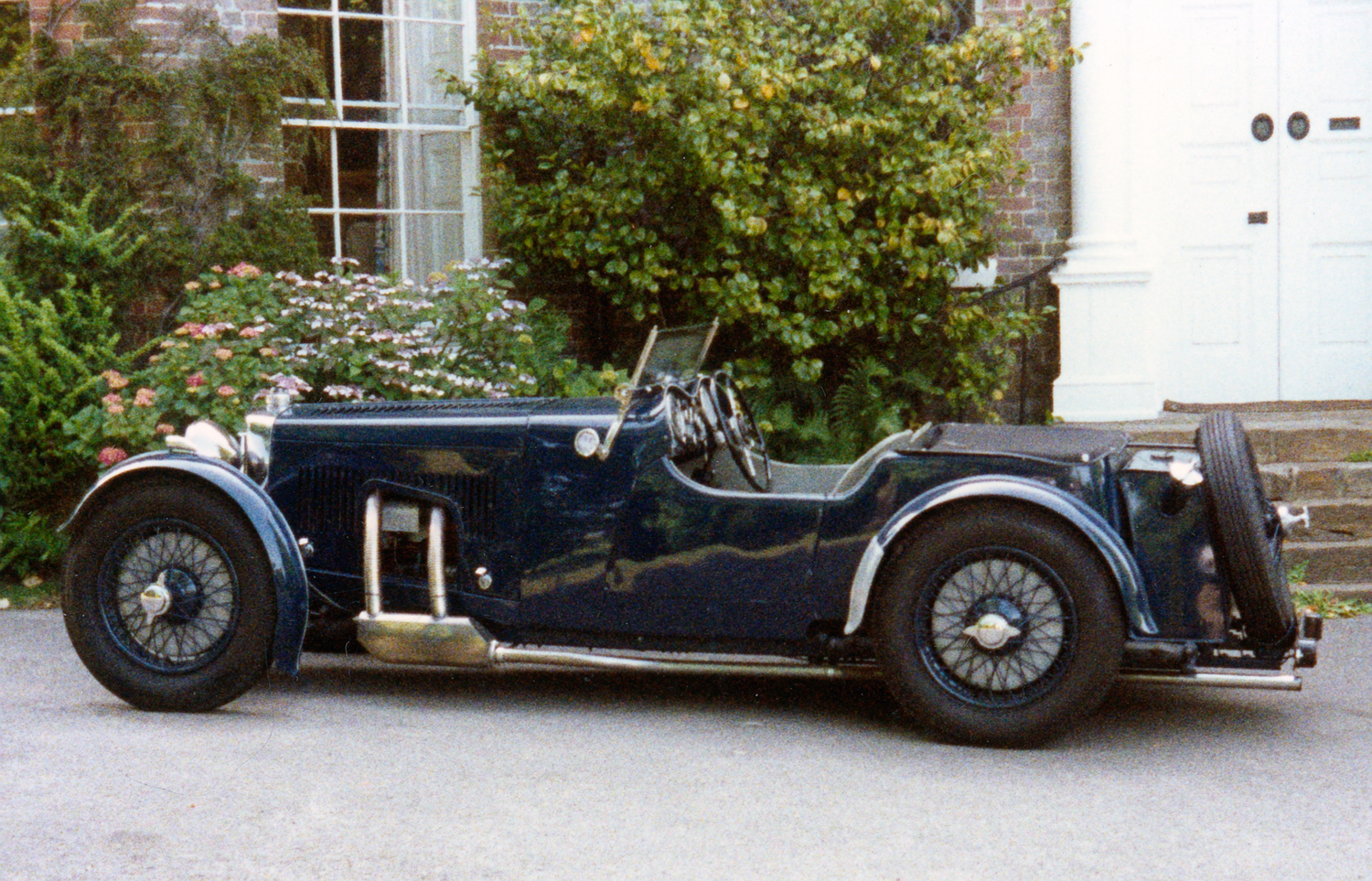

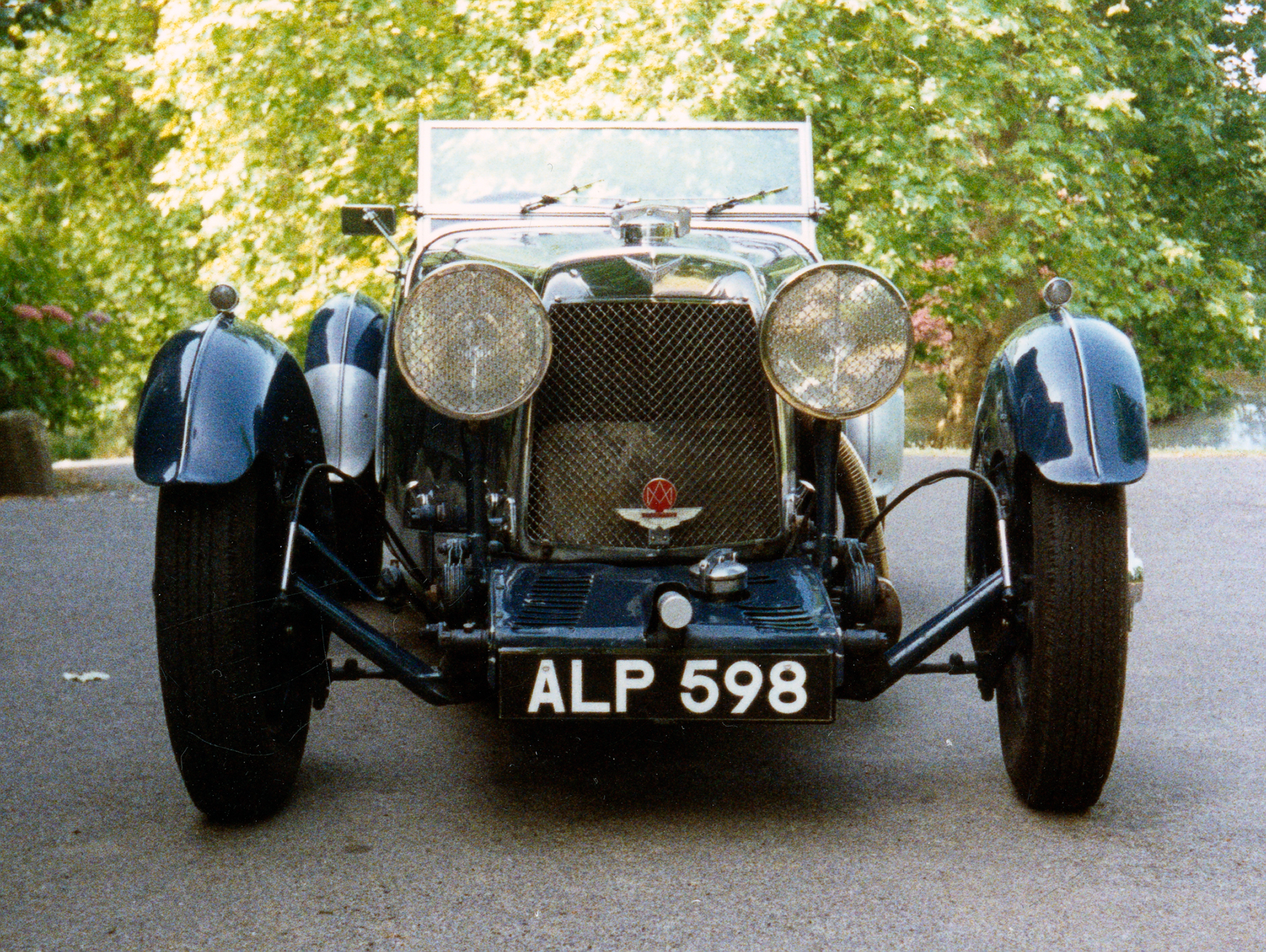

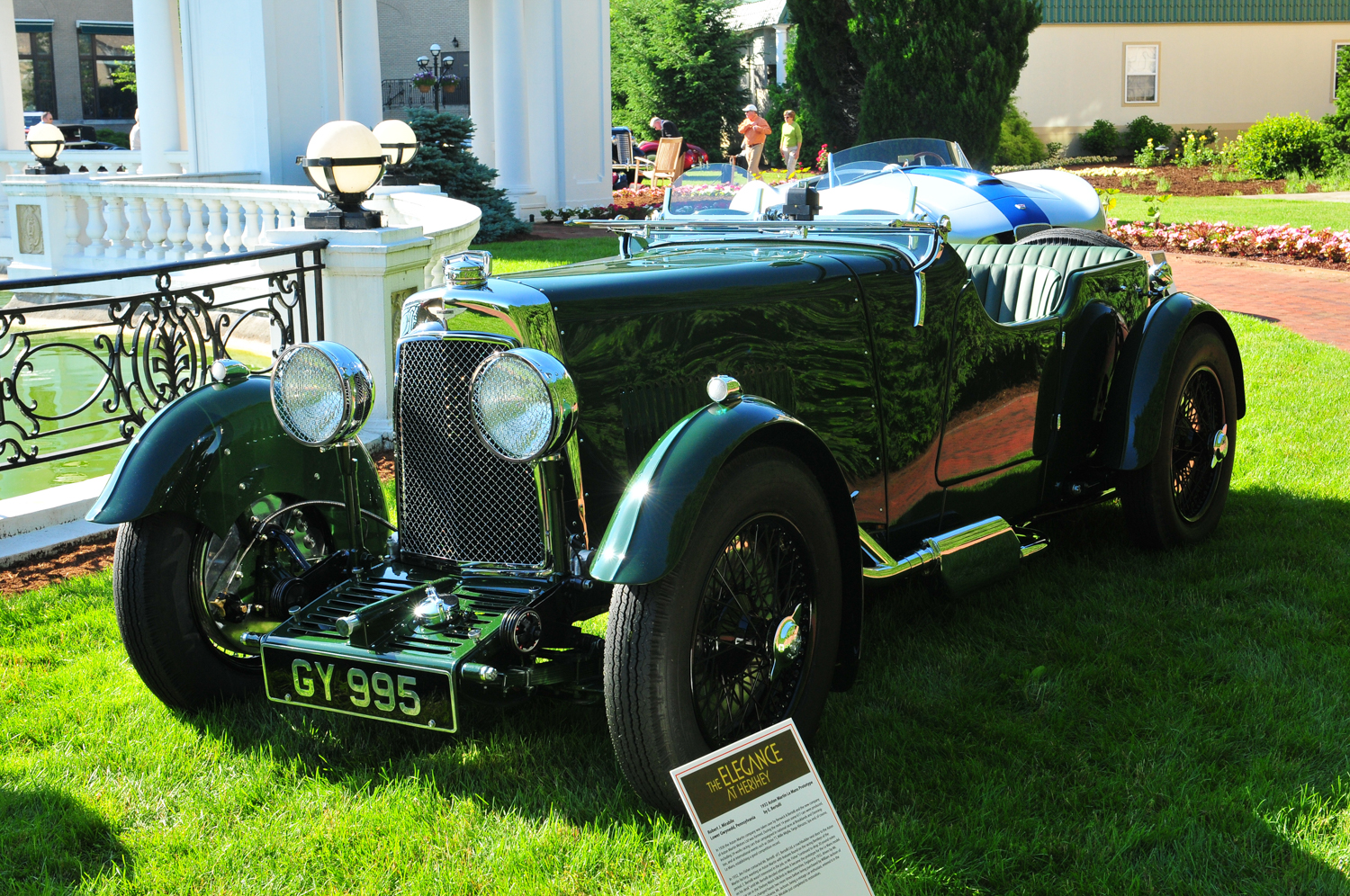

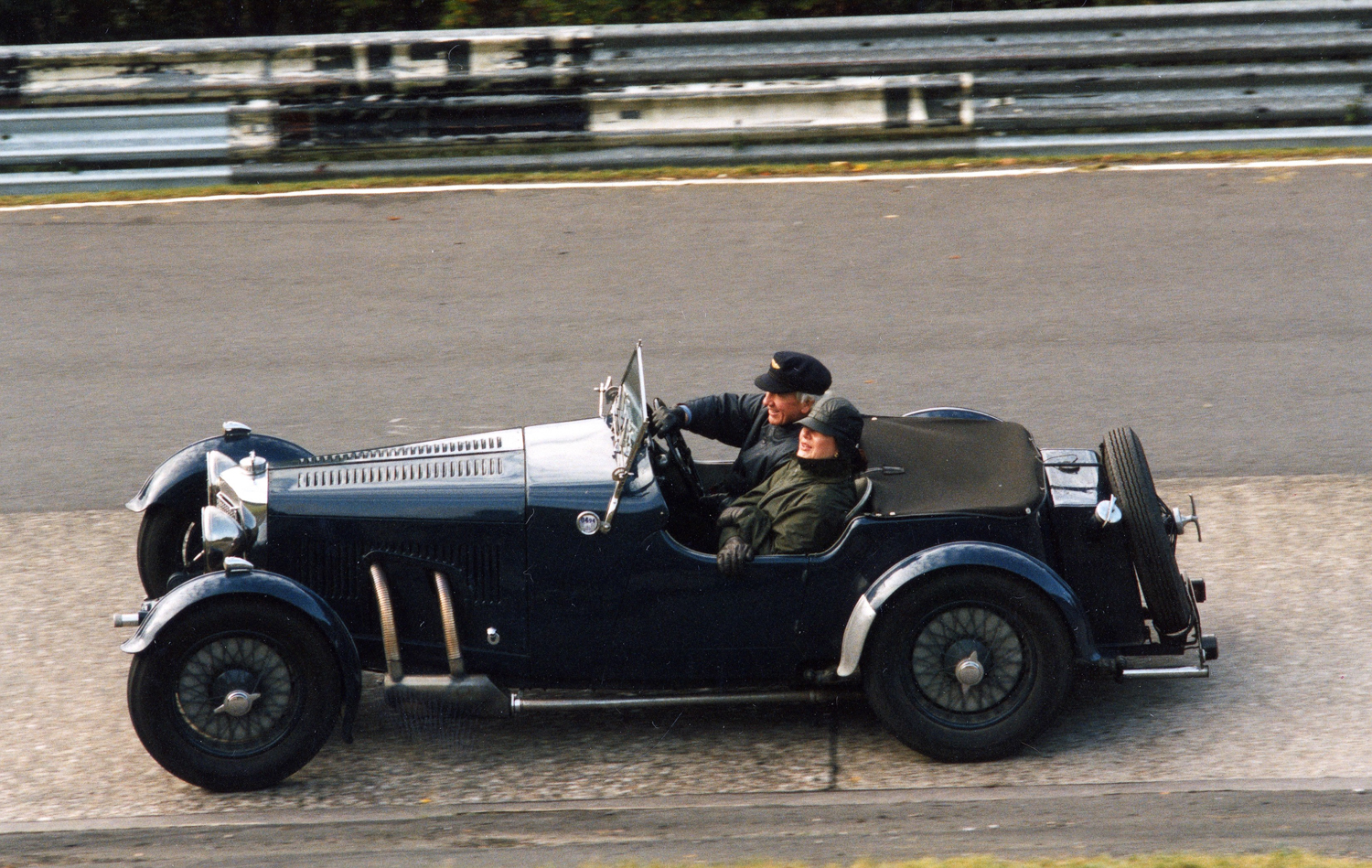

I made several stops before arriving at the showroom windows of Coys, which deserved its description as “the best toy shop in London.” There were the usual massive Bentleys, Rolls-Royces and Mercedes-Benzes. But parked athwart one window, the better to show off its low-built lines and outside exhaust pipes, was a Prussian Blue Aston Martin. It looked sensational: the quintessence of mid-’30s British sports car with its cycle fenders, liberal louvering, stone guards and slab fuel tank. Until then I hadn’t had a thought of acquiring a 1933 Aston Martin, but six weeks later I gave myself ALP 598 as a belated Christmas present.

I discovered I had a lot to learn about pre-war Aston Martins. I knew the factory team cars had done well at Le Mans. Thirty years ago I had driven and written about one of the rare 1935 Ulster two-seaters. I was also aware that the marque’s binary designation came from the names of its original creator, Lionel Martin, and the Aston Clinton hillclimb in which he had done well before World War I. Beyond that I would have flunked a quiz about Astons older than the DB-2.

A check of my car’s serial number, D3/225/S, in the excellent records of the Aston Martin Owners Club assured me that it was as it had been built by the factory in April 1933, a short-chassis Le Mans model with its original engine. This was important because many cars masquerading as such were actually cut down from 120-inch-wheelbase Astons to the 102 inches of the Le Mans. This was not always sensible because a knowledgeable car man, famed actor Ralph Richardson, much preferred the ride and handling of the long-wheelbase four-passenger version. But the shorter ones looked more sporty.

Aston Martin Limited made eight cars that month of April, in its factory on Victoria Road at Feltham, Middlesex, south-east of today’s Heathrow Airport. All but one of the eight were short-wheelbase cars like mine, series production of which had begun at the end of January 1933. In fact, the Le Mans model accounted for 85 of the 130 cars that Aston Martin made on the 1.5-liter Second Series chassis between February 1932 and December 1933. Considering that up to 1932 the total production of Aston Martins of all types since the first prototype in 1914 and the start of manufacture in 1922 amounted to no more than 200 cars, the Le Mans was a staggering success.

The Aston Martin Club lost sight of ALP 598 for a decade or so. They told me that it placed third in class in a Club concours in 1960 and then, after a restoration, was class winner in a 1973 concours. Since then it had aged gracefully to look like a well-kept 10-year-old Aston Martin. The impression that it hadn’t been driven much lately was given by such problems as out-of-balance wheels and excessive oil leaks that would have bedeviled anyone actually using the car, as I did, for serious driving in the English countryside.

What was the special appeal of the Le Mans model that attracted 85 buyers in 1933 and this particular buyer in 1982? In essence it was that Aston Martin had designed a more practical chassis for its 1932-1933 models without sacrificing the longevity and toughness for which its cars had become famous. Then they clothed it in handsome bodywork that was inspired by the low lines of the factory Le Mans racing cars. Also influential was a reduction in price to £595, although it was still more costly than other British sports cars of similar engine size.

The combination was attractive. Wrote Ted Inman Hunter, who worked for Aston Martin in those days, “Certainly the new car was the finest Aston Martin to emanate from Feltham up to that time. Indeed, to many enthusiasts it remains the finest of them all.”

Credit for the success of the Second Series 1.5-liter cars was owed to several individuals. One was the company’s managing director, Augustus Cesare Bertelli. Born in Italy and reared in Wales, Bert Bertelli had been with the company since 1926. Beyond being an engineer and entrepreneur, he was also well able to drive his cars at racing speeds. His elder brother Enrico, better-known as Harry, managed an independent coachbuilding company within the Feltham works. His drawings, full-size in chalk on a blackboard, resulted in the lines of the Le Mans.

The financial investment that the company needed for the new chassis design came from the Winter Garden Garage in London’s theater district in return for exclusive sales rights. Winter Garden was the property of Lance Prideaux Brune, who believed in demonstrating the car’s virtues in competition. The backing required to boost the production in 1933 was provided by the Sutherland family. Shipping magnate Sir Arthur Sutherland had bought the controlling interest in Aston Martin later in 1932. His son R. Gordon Sutherland became joint managing director with Bert Bertelli.

For the new mode, substantial improvements were made in the four-cylinder engine that had powered all Aston Martins since 1927. Its original design was the work of William Somerville Renwick, who had once been in partnership with Bert Bertelli. Influenced by the ideas of turbulent combustion chambers being put forward by Harry Ricardo, Renwick gave the engine a chamber elongated laterally. He positioned the exhaust valve directly above the piston with the inlet valve offset to the side in a pocket that also contained the 18-mm spark plug.

The stems of the overhead valves were parallel to each other and inclined at 14 degrees to the left to give the chamber the shape of a doorstop. Both inlets and exhausts had 39 mm valves seating on 35 mm ports. A deeper head casting for the revised engine gave better cooling and improved port shapes, siamesed on the inlet side to suit the use of twin SU carburetors.

Squish areas were added above the dome-topped pistons to bring the compression ratio of the Le Mans engine to 7.5:1, high for the era. Bore and stroke were 69.3 x 99.0 mm, giving a capacity of 1,494 cc. These cylinder dimensions were practically identical to those of contemporary Italian sports engines, such as the Maserati fours and eights and the Alfa Romeo Tipo B.

A single overhead camshaft opened the valves through pivoted fingers. Eccentrics at the pivot points accounted for part of the valve clearance adjustment. It was also variable by the height of the valve-spring retainers, which screwed onto the valve stems—a new feature of the 1932-1933 engine. A duplex chain running at half engine speed drove the camshaft from a pack of accessory gears at the front of the block.

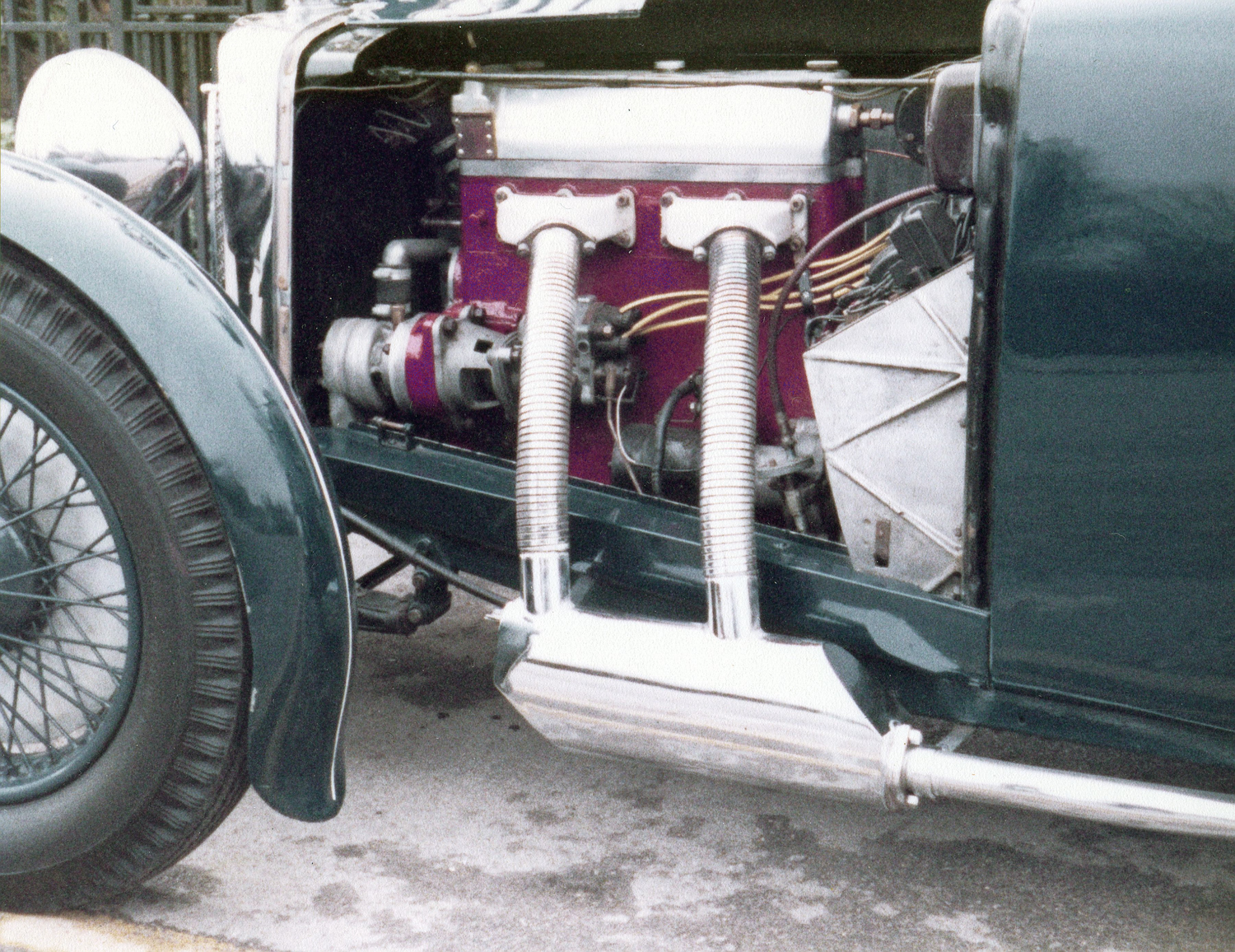

A gear train to the left of the engine turned the water pump and, along the left side of the block, the British Thomson-Houston magneto. The generator was driven directly from the front of the engine. So were a pair of oil pumps, for the Le Mans has a dry-sump lubrication system, a novelty in its time for a road car and still unusual today. The extra pump scavenged oil from the aluminum sump and delivered it to a reservoir. Placed between the front frame dumb-irons, this was exposed to a cooling flow of air. Dry-sump oiling contributed to the lowness of the Le Mans chassis and was a distinctive feature of all the most sporting Aston Martins from 1928 to WWII.

The head and the deep-sided cylinder block were cast iron. Three main bearings carried the steel crankshaft while the long connecting rods were made of aluminum alloy. A massive 24-pound flywheel and Borg & Beck clutch completed the engine, which was attached to the frame by four tubular arms. When new it was rated at 70 bhp at 4,750 rpm, a very respectable figure for a 1.5-liter road car more than 80 years ago.

Except for its Standard and New International cars, Aston Martin had always made its own transmissions. The Le Mans gearbox was simple, light and tough in an aluminum case with four speeds, the indirect ratios being selected by sliding the straight-cut gears into engagement. E.N.V. supplied the spiral-bevel rear axle; in ALP 598 the gear carrier is aluminum.

The chassis was an absolutely classical affair with semi-elliptic leaf springs, friction dampers and a forged-steel front axle with tubular ends. At the rear the deep channel-steel frame passed under the axle to lower the center of gravity and assist the building of low-profile bodywork.

The new series was launched with 21-inch wheels but soon became available with 18-inch wheels, which mine had, with tire sections of 5.25 front and 5.50 rear. Huge brakes with 14-inch aluminum drums were operated by cables with an individual adjuster for wear and balance at each wheel.

Front and rear tracks were 54.0 and 53.0 inches respectively and the wheelbase was 102.0 inches as mentioned earlier. This was by no means small for a 1.5-liter car. The early-1930s Aston Martin deserves its reputation for being heavy in relation to engine size. The factory-quoted figure for the Le Mans was 19 hundredweight or 2,130 pounds. Of the 85 Le Mans models made, 17 were on the longer wheelbase of ten feet fitted with full four-seater bodies.

Harry Bertelli did his best to keep the overall weight under control by paneling the body in aluminum over an ash frame. The cast-aluminum firewall was provided by Aston Martin. Steel was used for the helmet-type fenders, which were carried as unsprung weight attached to the brake backing plates at all four wheels. This accounted for the car’s very tight, trim look. Such fenders, first shown on a prototype at the Olympia Show in 1927, were generally adopted on Aston Martins in 1928 and became a characteristic feature of the make.

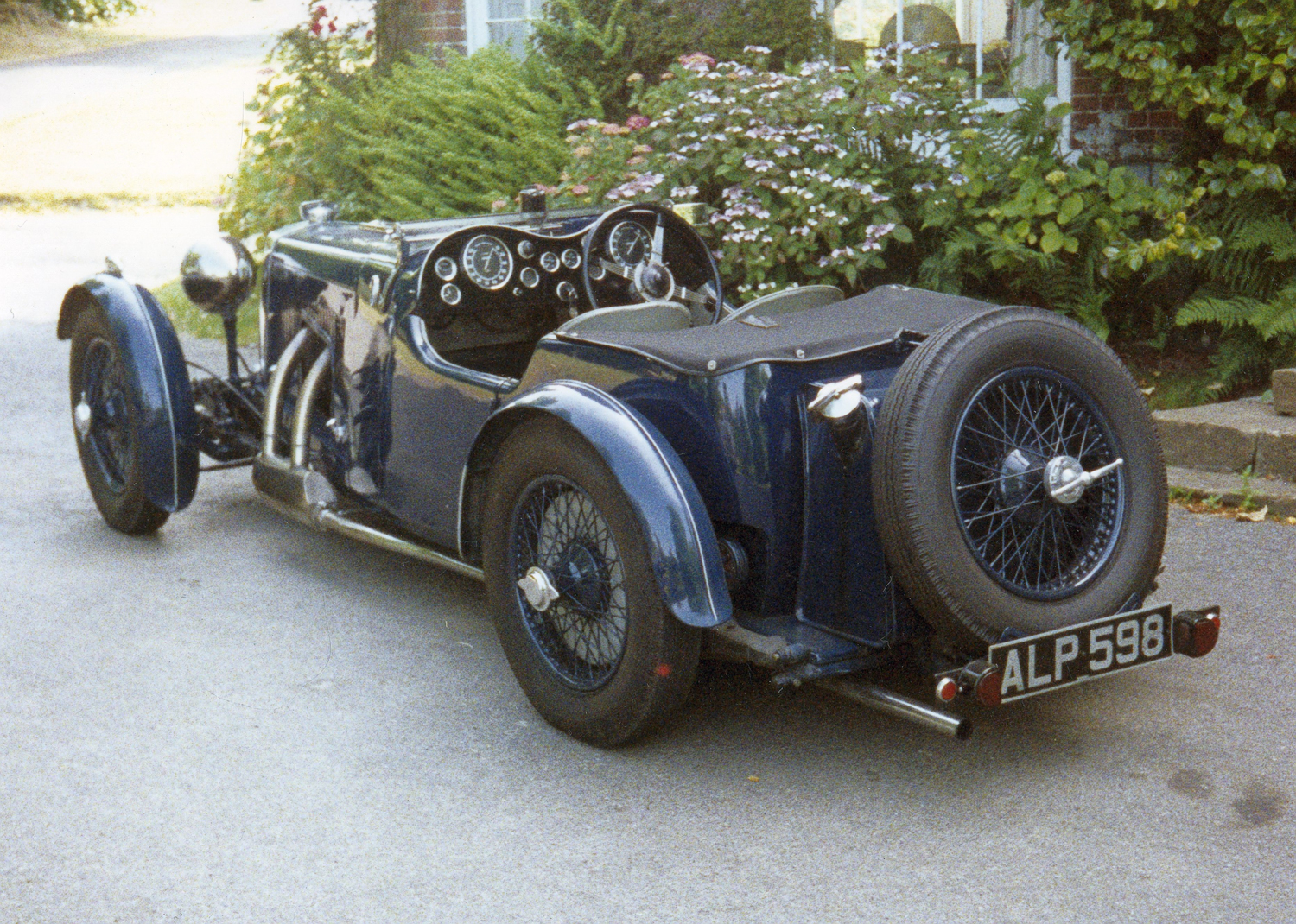

Among the 1.5-liter production Astons the Le Mans was unique in having a raised twin-cowl dash, carried over from the works racing cars. On this model Harry Bertelli also managed to stow the folded top entirely within the tonneau, which gives a much cleaner look at some sacrifice of storage space with the top down.

Several features of ALP 598 showed that along the way an owner wanted differences from the standard Le Mans specification. It was fitted with large and powerful Marchal headlamps, for example. Someone installed a fuel gauge, which worked as poorly as it looked. The real fuel gauge on this car is its system of dual Autopulse fuel pumps, one drawing from a lower point in the tank than the other. You run on the higher outlet and switch over to the lower pump when the engine sputters to a stop.

An archivist would have to dig deeper than I have to prove my suspicion that this Aston Martin model was the first car named after the Le Mans race. Since then, makes as diverse as Singer, Frazer-Nash, Ferrari and Pontiac have had Le Mans models but I haven’t found one that antedates Aston Martin.

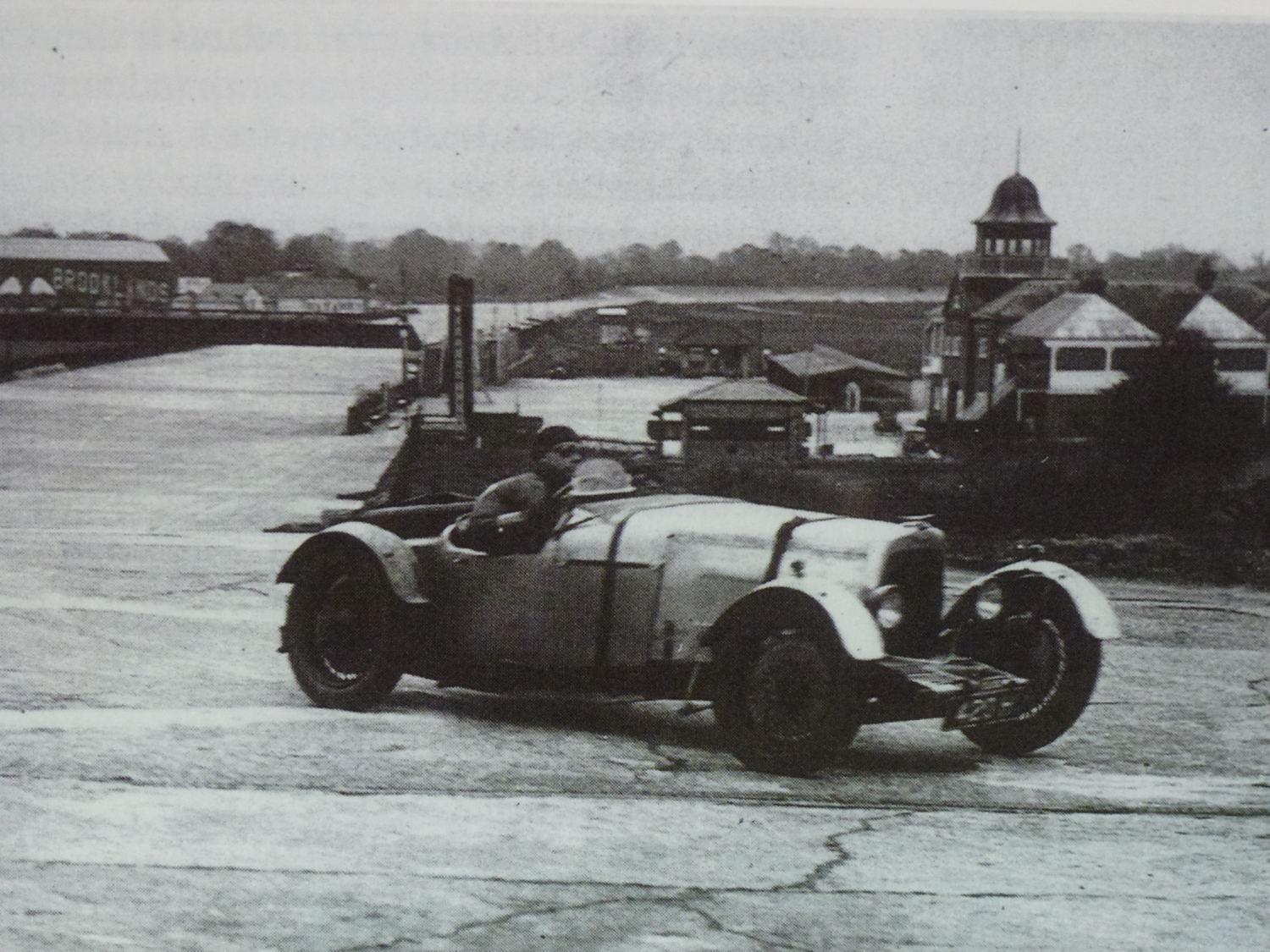

Justification for the name was Aston’s class victory and fifth place overall in the 1931 race by a works car driven by Bert Bertelli and Charles Maurice Harvey. After the name was announced it was made even more appropriate by placings in fifth and seventh in 1932 and the award of the Rudge-Whitworth Biennial Cup.

A production Le Mans—serial number B3/239/S, built in February of 1933 for Gordon Sutherland—was loaned to several magazines for road testing. Maximum speeds in the indirect gears were reported as 25, 45 and 65 mph without violating the 4,750-rpm limit. Both The Autocar and Motor Sport timed the top speed as slightly better than 81 mph with the screen up and 85 mph with it folded flat. This verified the top speed that Aston guaranteed to be 84 mph. Nought to 60 took Motor Sport 21.0 seconds and The Autocar no less than 24.6 seconds.

What we consider sluggish performance today was called then by The Autocar “really fierce acceleration through the gears.” The magazine’s view in July 1933 was that “this Le Mans model of the latest type now tested is about as near a racing machine as it is possible to buy for practical and general use on the road.”

The testers couldn’t fail to remark on the whine, especially under full throttle, of the spur transmission gears. I found the shifting delightful, light and easy with a tiny gate and very short travel between top and third. By all accounts this was much better than the shift on the preceding International model. Appropriately for a right-hand-drive car the shift pattern has first and second on the right and third and fourth on the left, where the lever is out of the driver’s way most of the time. This took some getting used to, as did the central throttle pedal.

After the magneto was rebuilt ALP 598 started at the first push of the button with a tug on mixture enrichment and full spark retard. At idle it had a “pocketa-pocketa “ rumble that would delight Walter Mitty while under acceleration the exhaust had a deep-throated snarl.

Watch an Aston Martin Le Mans in action on the Prescott Hillclimb.

Belying its unimpressive statistics, the Aston felt remarkably punchy. At revs over 4,000 a storm of mechanical noise broke under the hood, discouraging prolonged exploration of that region. Four thousand on the big chronometric tach was a good cruising pace around 70 mph, the cooling so effective that a radiator mask had to be used most of the time. Despite the lack of a fan I had only a couple of anxious moments in heavy traffic.

From behind its wheel the Le Mans is obviously a much larger car than, say, an MG TC. With light and direct steering it has a nice way of going where you aim it, getting good grip through corners from its low center of gravity and wide track. The ride is as bouncy as you’d expect from the car’s layout but the long wheelbase kept it from being excessively choppy. A strong push on the pedal gives good stopping but when the huge brakes are wet they want careful watching.

When I bought ALP 598 I did so with the reassuring feeling that the world expert in the repair and restoration of pre-war Aston Martins, Morntane Engineering, was only two miles from my house. Backed by Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason, a keen car enthusiast, Morntane was captained by Derrick Edwards, for many years a racer of an Aston Martin Ulster. He assured me that although my car sounded like a threshing machine at idle, they all did.

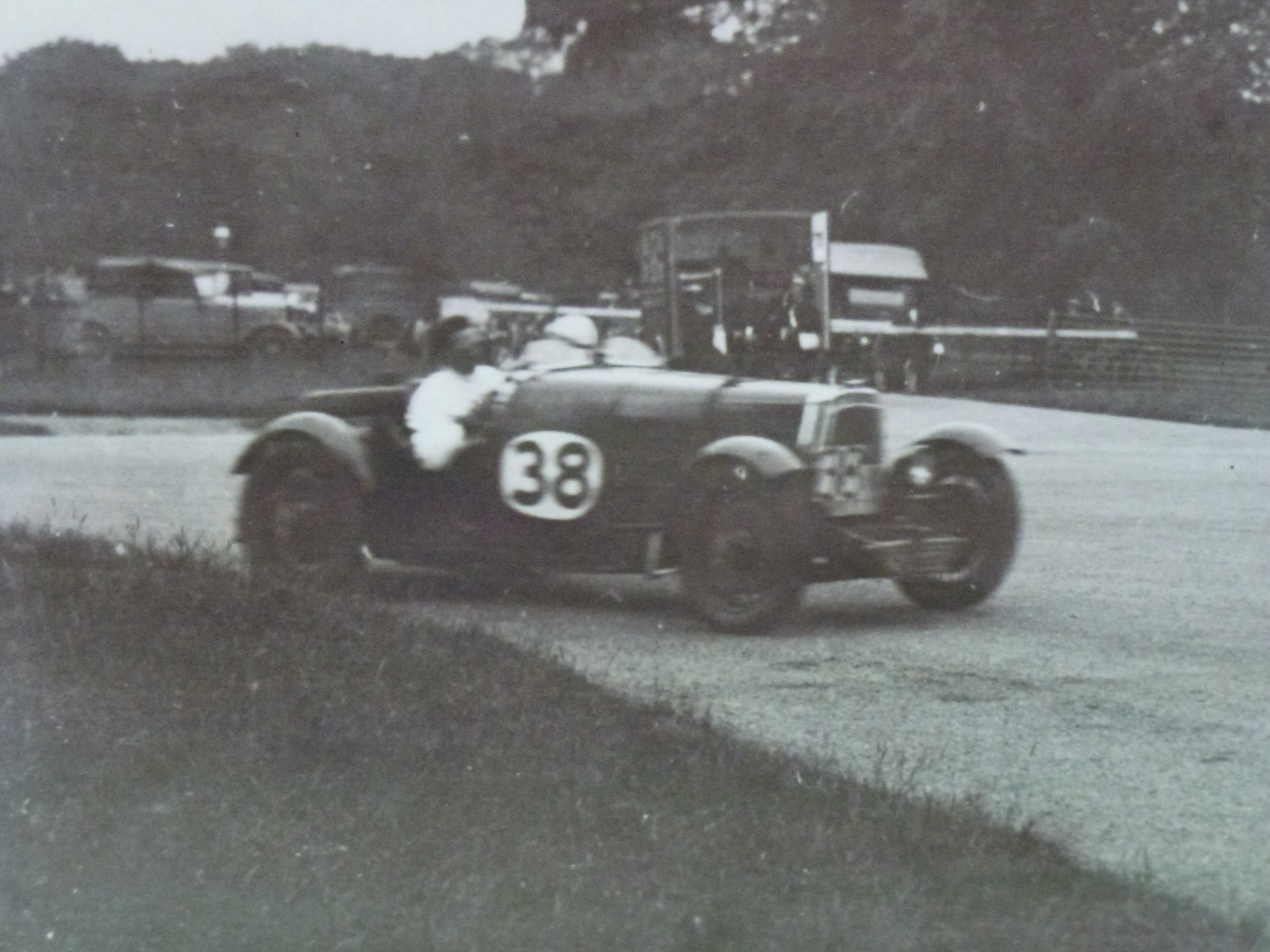

Keen on racing as they all were, the Morntane folks talked me into competing with ALP. I had three outings with her, one at Silverstone, another at Oulton Park and the last one at Brands Hatch. My son Miles was my pit crew at Silverstone, where we didn’t bother to check the oil level in the reservoir between qualifying and the race. ALP went well, really taking to the club circuit and placing decently among similar cars.

Before driving back to London after the race Miles and I checked the oil and found it alarmingly low. Obviously we should have looked at it earlier. But here we found a race-bred feature of the Le Mans. The outlet from the tank was at the bottom on the left-hand side, just where the very last drop of oil would be available when competing on a clockwise circuit, as were most in Europe including Le Mans. Bertelli’s development saved us.

I was looking forward to competing at Oulton Park, an interesting hilly and scenic circuit. At first practice went well but then the Aston started acting up, running sluggishly with a smoky exhaust. Not good. It turned out the that scavenge pump was no longer scavenging so oil was staying in places it shouldn’t. She went back to Morntane—on a trailer.

At Brands Hatch ALP and I enjoyed the club version of this short but challenging circuit. In practice we clocked times a shade better than another Le Mans so I thought we would wax him in the race. At the start, however, he just motored away! His engine was anything but standard! After Brands I decided that by racing I was only wearing out what was a perfectly good road car. I wasn’t prepared to go the full Morntane with racing modifications.

A few years ago we saw ALP again at Silverstone. Only her Prussian Blue color was the same! She had been ‘restored’ to within an inch of her life, the powerful Marchal headlamps gone along with the white pinstriping of her coachwork highlights. A comfortable, roadable Le Mans had been turned into a primped showpiece. Considering the six-figure prices these cars sell for now, I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised.