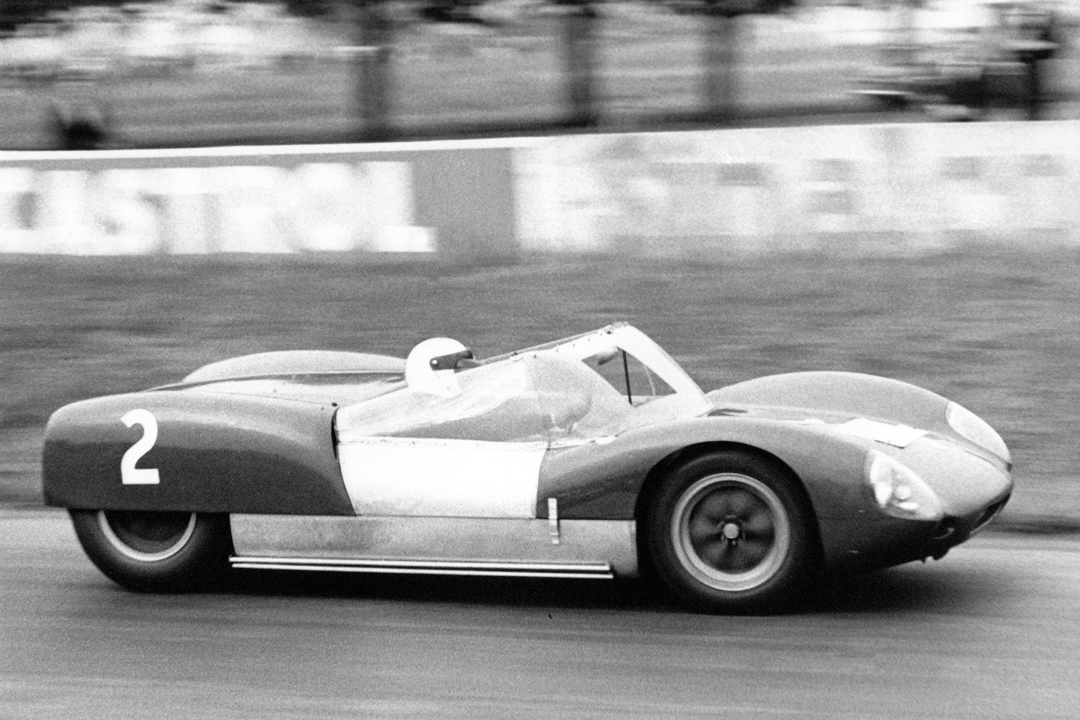

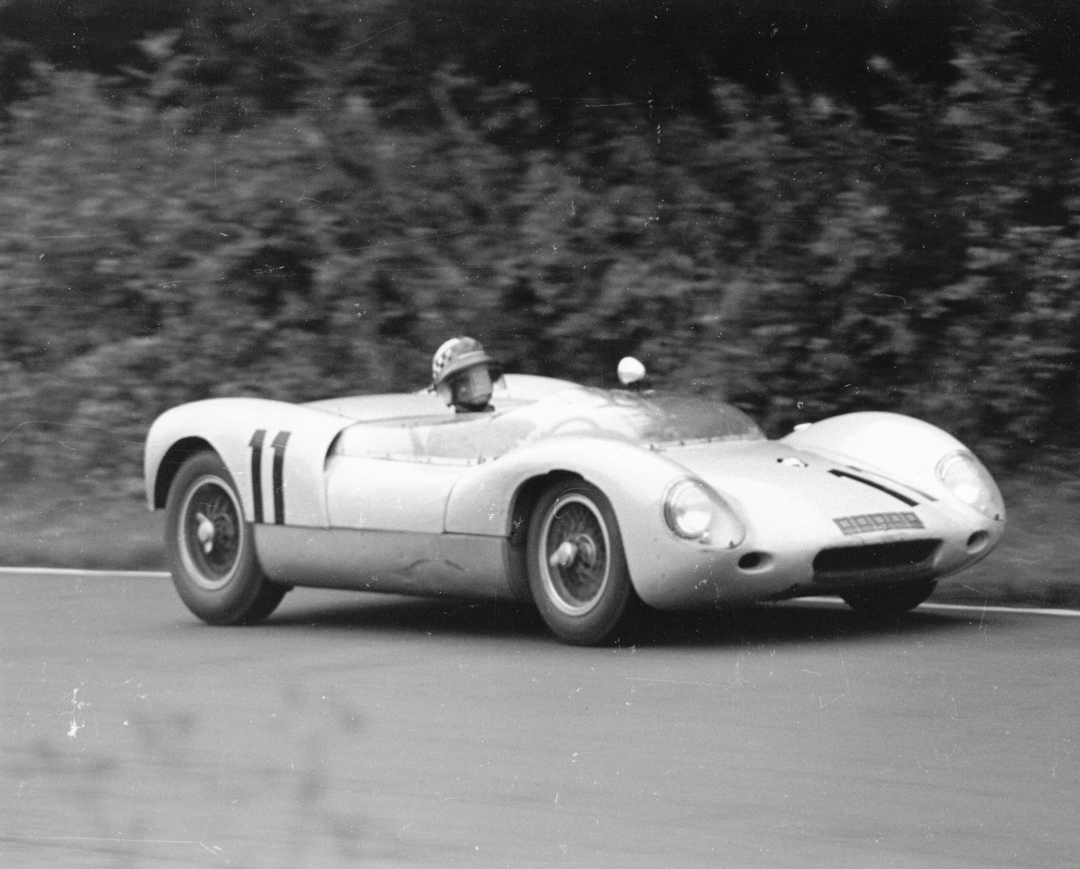

The Lotus 19 took sports car racing to a whole new level upon its debut in 1960, rendering rivals such as the Cooper Monaco and Maserati Birdcage obsolete overnight and leading photojournalist Pete Biro to label it the “Birdcage Cleaner.” A real “wolf in sheep’s clothing,” it was essentially a Lotus 18 Formula One car with the chassis widened to accommodate an extra seat, clothed in curvaceous all-enveloping bodywork. Michael Oliver profiles this rare beast, of which only a few genuine examples survive today.

The Lotus 19 “Monte Carlo,” given its tongue-in-cheek moniker by company founder Colin Chapman to mimic Cooper’s successful Monaco, was the first rear-engined Lotus sports car. Like the Monaco and the Lister-Jaguar before it, the 19 wasn’t really designed with endurance racing in mind, but for rather shorter, nonchampionship, international and national races instead.

With Cooper and Lola having taken over its traditional market in sports cars, Lotus was under pressure to reassert itself after the relative lack of success of its front-engined 15 and 17 models. It was, therefore, essential that this new car ran trouble-free and was quick straight out of the box. Chapman and his right-hand man, Mike Costin, didn’t rush to get it on sale for the start of 1960. Instead, they waited until they had their first rear-engined single-seater, the 18, sorted (in Formula One, Formula Two, and Formula Junior form) and then, by mid-season, turned their attention to the 19.

The Formula One 18 had quickly proved itself at the top level of the sport in the hands of drivers like Moss, Ireland, and Clark, so it seemed logical to base the design on that. In fact, the front and rear bulkheads were Formula One components and the two cars shared identical wheelbase, front and rear track measurements. The chassis itself was an exquisite triangulated structure of 1-inch and 3/4-inch, 16 and 18 gauge tubing, which diverged behind the front bulkhead in order to accommodate the two seats required by regulations of the time. A specially enlarged scuttle hoop of tubular and perforated sheet steel construction provided rigidity in the center of the chassis, as well as mountings for the steering column, gear lever, and instruments. From the scuttle hoop rearward, the chassis rails ran straight back to the engine bulkhead, then converged toward the rear bulkhead (through which the gearbox protruded).

Suspension consisted of double wishbones at the front, with the lower wishbone and driveshaft providing transverse location at the rear, combined with parallel rear radius arms picking up on the engine bulkhead. Motive power came from the Coventry Climax 2.5-liter FPF engine (shortly to become redundant in Formula One as a result of the introduction of the 1.5-liter formula), while the troublesome Lotus sequential gearbox (known colloquially as the Queerbox) was retained.

With the radiator and oil tank mounted in the nose, coolant and lubricant had to make their way fore and aft via external pipes, which looked quite exposed mounted on the sides of the chassis. Finally, braking was provided by outboard front discs and inboard rears, while the car sat on 15-inch cast magnesium “wobbly web” Lotus wheels.

The prototype—chassis #950—was finished early in August 1960. The car was made available by the works to Stirling Moss, who at the time was still recuperating in St. Thomas’s Hospital, London, from his mid-June Belgian Grand Prix practice accident at the wheel of Rob Walker’s Lotus 18, where he had broken both legs and his nose, as well as crushing three vertebrae.

Dick Tarrant, mechanic that day, takes up the story: “He left the hospital for the afternoon and somebody brought him up to Silverstone. He went out and broke the lap record by nearly one and a half seconds—amazing.”

The test also provided one of the only occasions when a 19 was driven by a woman, as Tarrant recalls: “Stirling’s sister Pat [an accomplished race and rally driver in her own right] had been on and on at him to let her have a go and, at the end of the afternoon, he did. So off she goes, and then she didn’t come back around. So Stirling said to me that I’d better go and find out what had happened to her. I said I’d take the van and trailer, but he said, ‘No, take Pat’s Saab.’

“I found her on Hangar Straight. She said it had just died, and we figured it had run out of petrol. So I said I’d go and fetch the trailer but she said, ‘No, give us your hand.’ Well, the Saab was left-hand drive and in the Lotus you sat on the right, so she just held on to me and I towed her all the way back around to the pits like that.”

One problem that showed up in early testing was that the gearbox oil was getting very hot and the brakes were fading, caused by the inboard discs and a lack of ventilation. Consequently, the car went back to the works and the discs were moved outboard and all subsequent cars were thus equipped.

On Sunday, August 7, 1960, the Yeoman Credit/BRP 19 took part in its first competitive event, the annual Kanonloppet race at Karlskoga in Sweden. Moss started from pole position, won the race, and set fastest lap in a display of complete dominance.

This was the only occasion the still-unpainted prototype competed in its original aluminum bodywork before the front and rear body panels were removed and used as a template for subsequent bodies made in fiberglass—although the bottom half of the center section and the doors remained in aluminum.

However, the prototype 19 had one more task to perform before its return to the UK—that of record-breaker. Jo Bonnier had persuaded his good friend Moss to lend him the car for a crack at the Swedish flying kilometer record, in Lund, in the south of the country. Mechanic Dick Tarrant fitted a taller top gear but otherwise the car was unchanged. Ironically, although Bonnier took the record at 157.5 mph, he managed it without ever getting out of fourth gear, the run-in to the measured kilometer featuring a dog-leg corner which compromised his approach speed.

The car returned to Lotus and continued its development program, being driven at Silverstone by both Mike Costin and Colin Chapman. It was painted in the pale green of Moss’s manager Ken Gregory’s British Racing Partnership and entered for two races in the United States—the Riverside Grand Prix and the Pacific Grand Prix, along with the first production 19, chassis number 951, for Dan Gurney, entered by Frank Arciero. Although the two 19s showed early pace at Riverside, they both went out early in the race, leaving Billy Krause to take a popular victory in his Birdcage. However, at Laguna, Moss won both heats unchallenged, as practice problems sidelined Gurney.

The writing was on the wall: Gurney had been some three and a half seconds inside the lap record at Riverside and only one driver got within two seconds of Moss in the race at Laguna. The two 19s traveled to Nassau in the Bahamas, where they both competed in two races in early December. In the first, the Governor’s Trophy, each retired but in the Nassau Trophy the next day, while Moss had another nonfinish, Gurney went on to win and take the first of many victories in the Arciero car.

By the start of 1961, production of customer cars was in full swing at Lotus Components’ Cheshunt base. The first to receive its cars was the British Racing Partnership, now running a “super-team” known as UDT-Laystall. They collected chassis numbers 952 and 953 from the works in February 1961, although one of these cars was at the time little more than a box of bits. With just one exception, the remaining production cars were destined for non-UK owners, the majority on the North American continent, with two going to Europe for hillclimbing.

Cars were not delivered according to chassis number but in order of urgency. Consequently, 960 was the next car collected, in March, since it was to appear at the Sebring 12 Hours in the hands of Fort Lauderdale native Robert Publicker, who was to share it with Charlie Kolb. Unfortunately, its 1.5-liter Climax blew in practice, so it did not start the race. Further attempts to run the car appear to have been frustrated by the Queerbox, since, when it was offered for sale in October 1961, it was with a Porsche RS transmission and “Lotus progressive box optional extra.”

In April, 957 was dispatched to Tacoma, Washington-based Tom Carstens, less engine, but he had decided to scale down his racing and it was eventually sold without having turned a wheel. In May, Swiss hillclimber Harry Zweifel collected his car (chassis 961) fitted with a 2-liter Climax engine and proceeded to take in eight rounds of the European Hillclimb Championship, scoring three class wins. He would later fit a variety of power units to his car including 2.0- and 2.9-liter Maserati engines.

In June an up-and-coming Canadian driver by the name of Pete Ryan took delivery of chassis 959, and the following month Charles Vogele, another Swiss hillclimber, collected 956. In September, 955 and 958 were dispatched to wealthy Los Angeles cosmetics heir Jack Nethercutt Jr., and former Porsche-peddling Floridian pilot, Roy Schechter, respectively. All of these cars were fitted with 2.5-liter FPFs.

In the meantime, UDT-Laystall’s three-car assault on major British sports car races had yielded a 1-2 at the opening meeting of the year at Goodwood, and then two successive 1-2-3 finishes at Oulton Park and Aintree, with drivers Henry Taylor, Cliff Allison, and Stirling Moss (with Graham Hill and Mike Parkes stepping in when Moss had other commitments).

However, their dominance came to an embarrassing halt at Crystal Palace in May. Trying out their new wire wheels with knock-on hubs in preparation for the forthcoming Nürburgring 1000 kilometres, both Taylor and Parkes lost their nearside rear wheel due, it transpired, to a fault in the manufacturing process, as team manager Tony Robinson recalls: “They weren’t heat-treated properly and their tensile strength just about corresponded to mild steel—they sheared off like carrots.”

With only a matter of days before they were due to depart for the Nürburgring, there was no option but to withdraw the cars. A single car (believed to be 952) was sent out to Mosport in Canada for the prestigious and lucrative Players 200 race in June, in which Moss scored an easy victory.

In August, Henry Taylor traveled up to a minor national meeting at Aintree, in a bid to restore his confidence following a crash in the British Grand Prix three weeks before which had left him with a couple of cracked ribs. He had been lucky to escape more serious injury, for a signpost had speared through the outer skin of his Lotus 18/21, through the fuel tank, across his lap, and out the other side, trapping him in the car. Driving one of the team’s 19s with a 2-liter Climax, he finished a morale-boosting 2nd and set fastest lap.

Two of the team’s cars then traveled out to Canada and the United States to take in some late-season big-money races, starting with the Canadian Grand Prix at Mosport on the last weekend in September. Although there is no doubt about the identity of one of the cars—953, which was competing in the 2-liter class driven by Belgian Olivier Gendebien—there is some uncertainty as to which of the other UDT cars went to this race and to the two events that followed, at Riverside and Laguna (either 950 or 952).

At Mosport, the troublesome Queerbox on the Moss car had been replaced by a Colotti unit, which was quite a bit heavier and bulkier than the Lotus ’box, necessitating removal of the upswept undertray at the rear of the car. However, photos of the car driven by Moss at Riverside and Laguna seem to show this in place, suggesting either a different car (e.g., 950) or that the team had reverted back to the Queerbox, which seems unlikely.

During the Mosport race, Moss, in the Colotti car, swapped the lead (more for entertainment of themselves and the crowd, it seems) with Gendebien in the Queerbox car, until everything unraveled in the latter stages, with the Briton forced to pit to have (ironically) gearbox maladies sorted and the Belgian’s crown wheel and pinion failing. Although Stirling was able to rejoin, he had lost several laps, leaving victory to Pete Ryan in his 19.

Around this time, Dan Gurney had also concluded that the Arciero Brothers’ 19 needed an extensive reworking to make it more robust. Among other things he decided that he too needed a Colotti Type 29 gearbox, and had one installed in time for the Riverside race. However, it also gave problems, losing him four laps, and he finished a lowly 9th overall. Meanwhile, Moss led the race handsomely at one stage, but pitted just before half-distance with a defective brake seal and was out. Gendebien salvaged Lotus pride by finishing 6th and taking the under-2-liter prize.

By Laguna, both Gurney and Moss seemed to have ironed out the niggles with their cars and proceeded to engage in a real humdinger of a battle in both heats of the race, with Moss leading home his American rival each time and Gendebien coming home 8th, taking the 2-liter class again. A sign of the growing popularity of the 19 was the fact that five cars were entered for this race, Pete Ryan finishing 7th overall and Nethercutt failing to qualify on the first outing with his car.

Schechter’s 958 entered the fray six days after Laguna, at the Pensacola Divisionals in Florida. Making a debut that was portentous of future troubles, the car suffered engine maladies on the Saturday and did not race in the main on the Sunday. Two weeks later at Geneva, it blew a head gasket in the prelim and did not start the main again.

At the end of the regular season, UDT-Laystall disposed of two of their 19s. Chassis 952 was sold to Texan Tom O’Connor’s Rosebud Racing team, while 950 was sold to the Australian driver Frank Matich. The team retained 953, easily identifiable by the absence of the oil and water pipes along the side of the chassis (these had been relocated early on in the car’s life).

Matich’s car first appeared at the Catalina Park meeting on January 21, 1962, but was generally delivered in a poor state of repair, in the end a broken crank during practice put paid to its weekend. A dispute subsequently arose with UDT, with Stirling Moss (who tested the car in Australia after it had been delivered to Matich) backing the buyer over his former team bosses.

Redress was eventually arranged and the car went on to be extremely successful in Australian sports car racing at that time, until it was shunted into the pit wall at Warwick Farm in 1963 by Matich’s mechanic, necessitating the supply of a replacement chassis. The new car, which was built up and raced in team sponsor Total’s white, red, and blue colors, became known unofficially as a 19B and used many Brabham parts, including wheels and suspension. It, too, was a consistent front-runner, until a July 1965 practice crash at Lakeside caused sufficient damage for it to be written off for good.

The Rosebud car, driven by Moss, raced in Nassau in December 1962, looking immaculate with wire wheels, knock-on hubs, and the cutaway bodywork around the rear wheels. It also featured a Colotti box, supporting the theory that it was this car that Moss had used in Canada in late September. Although the car was fast, it was still fragile, and he didn’t finish either of the races he started.

During 1962, Rosebud experimented with several different drivers, including Pedro Rodriguez (at Daytona in February), Olivier Gendebien (Players 200 at Mosport in June), and Pete Lovely, who raced on two successive weekends in June at Laguna and West Delta Park, breaking the crankshaft on the 2.5-liter engine in the latter. When the car returned to the tracks in September 1962, it was running a 2-liter FPF (with Innes Ireland now the regular driver) and continued to do so for the rest of the year.

Ireland was also sharing the regular driving duties of the UDT car in the UK with Masten Gregory and, on one occasion, world champion-to-be Graham Hill. Whoever drove, it proved virtually unbeatable, winning six out of seven races and finishing 2nd in the other. When it ventured abroad, it was also extremely competitive, winning the Players 200 and the Canadian Grand Prix in September (both at Mosport) each time with Gregory aboard.

Dan Gurney continued to campaign the Arciero car during 1962, scoring a popular win at the Daytona Continental meeting in February, where he broke a crankshaft in the dying laps but was sufficiently far ahead to be able to park up at the top of the banking and then roll the car over the line using gravity to get it moving to take the checkered flag. Although some insist that he wound the car over the line on the starter motor, the man himself denies this, all these years later.

Meanwhile, several new names were cropping up on the list of Lotus 19 drivers. After another DNF in the Osceola Grand Prix at Sanford in July 1962, Roy Schechter gave up the unequal struggle with his car. “I just couldn’t finish a race in that car. We couldn’t keep the gearbox together. We did everything, we made new gears but it made no difference.” He sold it to the Causey brothers, Dave and Dean, based out of Carmel, Indiana, who broke up the tedium of the long drive home by unloading the car and driving it on the road for a time.

The Publicker car, 960, also reappeared in June 1962, in the hands of Chicago-region racer Tom Terrell, who proceeded to drive it in a host of races in his area, with a 2-liter Climax fitted, before selling it to Wisconsin driver Doug Thiem.

Meanwhile, the Ryan car (959) had been acquired by Francis Bradley and made its first appearance in the Players 200 at Mosport in June 1962. It won the Canadian Championship in 1962 in Bradley’s hands, and then repeated the feat the following year, this time driven by Dennis Coad.

Three new cars appeared in September/October 1962, these being J. Frank Harrison’s 954, prepared by former Arciero-mechanic Jerry Eisert, the ex-Carstens 957, now in the hands of West Coast former Ferrari Testa Rossa racer Jerry Grant, plus a newly delivered 19, 962 for Californian Lotus subdealer Rod Carveth. Carveth’s car was supplied less engine but with a Colotti Type 29 gearbox, reflecting his desire to fit a 214-ci (3.5-liter) Buick V-8 into the engine bay, and the consequent need for a robust transmission to cope with the power, while Grant’s car was also Buick-powered. The Harrison car, for Lloyd Ruby, was fitted with the standard 2.5-liter Climax.

These three cars all made their race debuts at the same meeting—October’s L.A. Times Grand Prix at Riverside. Although not the first rear-engined sports cars to feature V-8 engines (Bob McKee had converted a Cooper Monaco for Rodger Ward in 1961), Carveth and Grant’s mounts were the first examples of Lotus cars fitted with “big-banger” V-8 engines and the forerunners to the USRRC cars that would morph into the Can-Am series.

They were joined by a further five 19s—the Arciero car for Gurney, Rosebud’s 952 for Ireland, the UDT 953 for Gregory, Nethercutt’s 955, and Dave Causey in 958. Best-placed finisher was Gregory in 3rd, victory going to Roger Penske in the center-seat Zerex Special, based on a Cooper Formula One car, while Ireland finished 5th to claim the 2-liter spoils.

A week later, the “circus” moved on to Laguna Seca for the two-heat Pacific Grand Prix. Although not quite as spectacular, the Lotus 19 entry still ran to six cars. While Gurney won the first heat, he suffered a broken gearshaft in the second, leaving Penske to win again from Ruby in the Harrison 19.

Three more 19s joined the fray for the 1963 season. Chassis 963 was delivered at the end of 1962 to Bob Colombosian of Woburn, Massachusetts, who had bought it with his partners in the Autolab garage business, Henry Olds and John Todd. In the UK, John Coundley acquired 964, to which he fitted a 2.7-liter FPF engine, while the Texas-based Mecom Racing Team, owned and run by John Mecom, Jr., bought a rolling chassis into which they installed a 2-liter Climax for their driver Augie Pabst to race.

By the end of 1962, Team Rosebud’s chief mechanic Jock Ross had concluded that the 2.5-liter FPF was becoming uncompetitive, when pitted against larger capacity, torquier, and more powerful units, so he set about fitting a 3-liter Ferrari V-12 into 952. It was an exquisite piece of engineering, shoehorned into the engine bay, and the car made a wonderful noise.

Unfortunately, on its first outing, Innes managed to crash it into a marshal’s parked car, putting him in the hospital with a dislocated hip, writing off the 19, and damaging the vehicle he hit. Chassis 952 was subsequently rebuilt with the Ferrari V-12 (it is not clear how much of the original chassis was incorporated in the rebuilt car) and continued to race until the end of 1964.

Back in the UK, UDT continued to campaign the old warhorse 953 throughout 1963 in domestic races, although it was not as successful as in previous years. It was also shipped out to Canada in June for Graham Hill to drive in Mosport’s Players 200, where it joined another six 19s on the grid. Clearly the design might have been getting long in the tooth, but it remained a popular choice for this type of race. A 19 won, too, in the hands of Chuck Daigh, driving the Arciero car formerly piloted by Gurney.

The final evolution of the 19 came with chassis 966, the only car designated 19B to leave the Lotus factory. In fact, according to designer Len Terry, it had very little in common with other 19s. “It was completely different, even though the bodywork looked quite similar. We took the body mould, slit it down the middle, and added four or five inches to give it greater width due to increased tire sizes. I also put in a much more complicated space-frame chassis. It was a completely new design—Colin Chapman gave me “carte blanche”—I didn’t even refer to the 19 drawings. He wanted to sell Dan a Lotus 30, but Dan didn’t want to know. So, he said that he would get me to design a car for Dan, and the 19B was the result.”

The new car, powered by a 289-ci (4.7-liter) Ford Fairlane V-8, was delivered to Gurney just in time for the Nassau Speed Week in December 1963. Although the car was not ready in time for the Governor’s Trophy, he managed to start the Nassau Trophy but retired early on with suspension troubles. When it raced in 1964, this car suffered from poor reliability with a series of DNFs, often let down by its Colotti gearbox. A revised version, the 19J, appeared at the 1965 Sebring 12 Hours with new bodywork and set off as the “hare” to try and draw out the Chaparrals, but retired early on and, shortly after this, Gurney sold the car.

Other 19 owners were quick to see the potential of the 1963 Fairlane 289 engine, too. Only a matter of days apart, at the end of September 1963, Lloyd Ruby had debuted the Harrison Special, which was 954 reworked with the Ford engine and new, Troutman & Barnes–supplied bodywork, while Canadian Norm Namerow had put one into 963, which he had acquired from Colombosian.

The next logical move was for owners to squeeze a big, powerful Chevy in the back, something tried by both the Arciero Brothers and Jerry Grant. However, back in 1960, when the 19 was conceived, it was designed to handle around half the power now being banged out by these ferocious 450-500-bhp monsters. By 1965, the space-frame design was beginning to show its age and was being superseded by stiffer and stronger monocoque chassis newcomers, such as the Lola T70 spyder.

Although 19s raced on as late as 1969, they quickly slipped down the tree of competitiveness and became obsolete racers, just as they had made the Birdcage obsolete on their introduction in 1960. The Lotus 19 filled a neat gap between the era of the front-engined sports cars and the evolution of the “big-banger” Can-Am cars. It was undoubtedly one of the fastest cars of its generation and, but for some reliability issues, would probably have been able to lay claim to being the most successful, too. Given their scarcity and rarity value, not too many are racing nowadays but, when driven well, they still have the capability to clean out a few ’cages.…