In the three-liter class, one of sports racing’s most competitive, Britain’s Aston Martin fancied its chances in international racing from 1951 through 1959. It was a saga of rising fortunes that culminated in the beautiful DBR1/300 of 1956-’59.

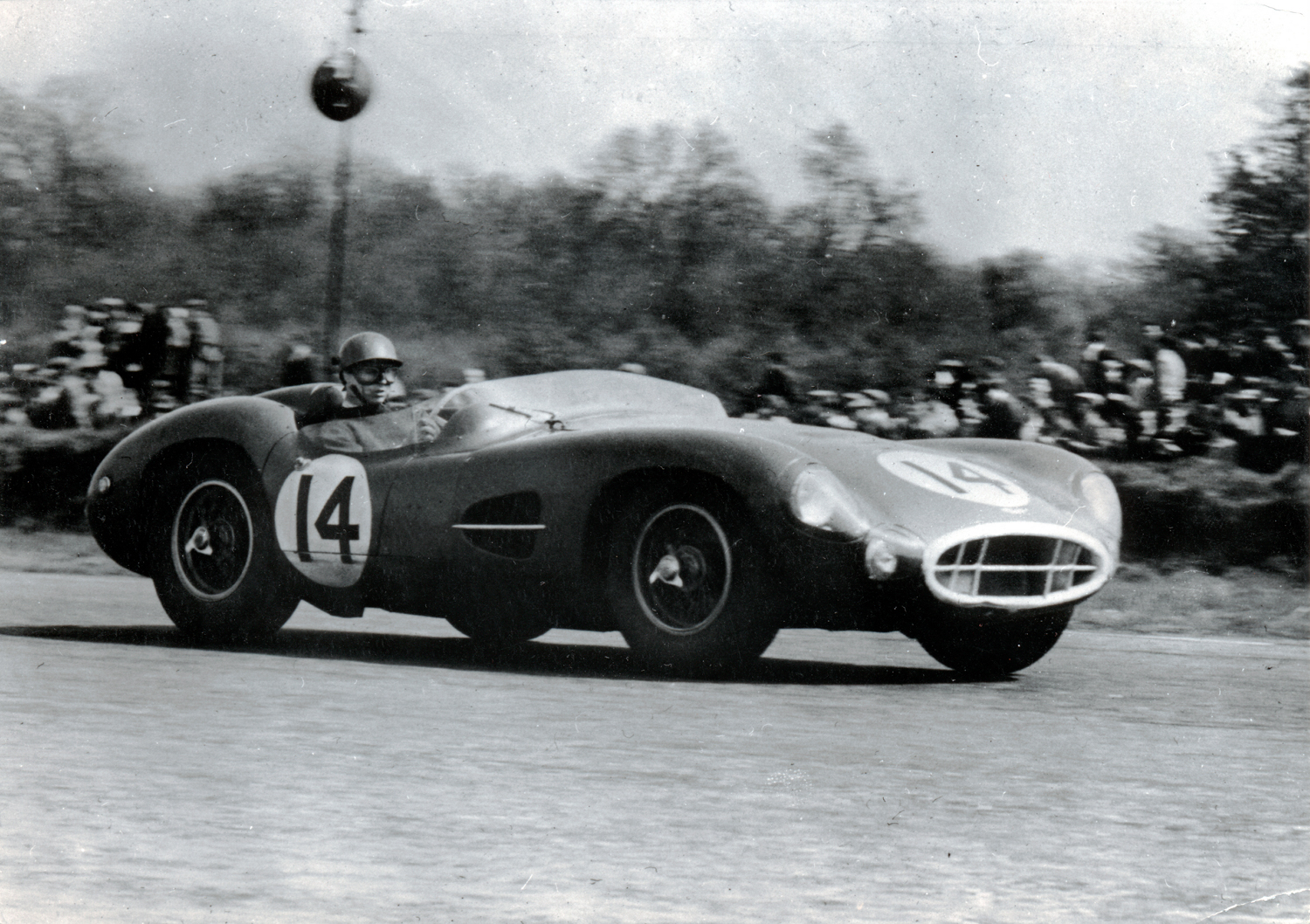

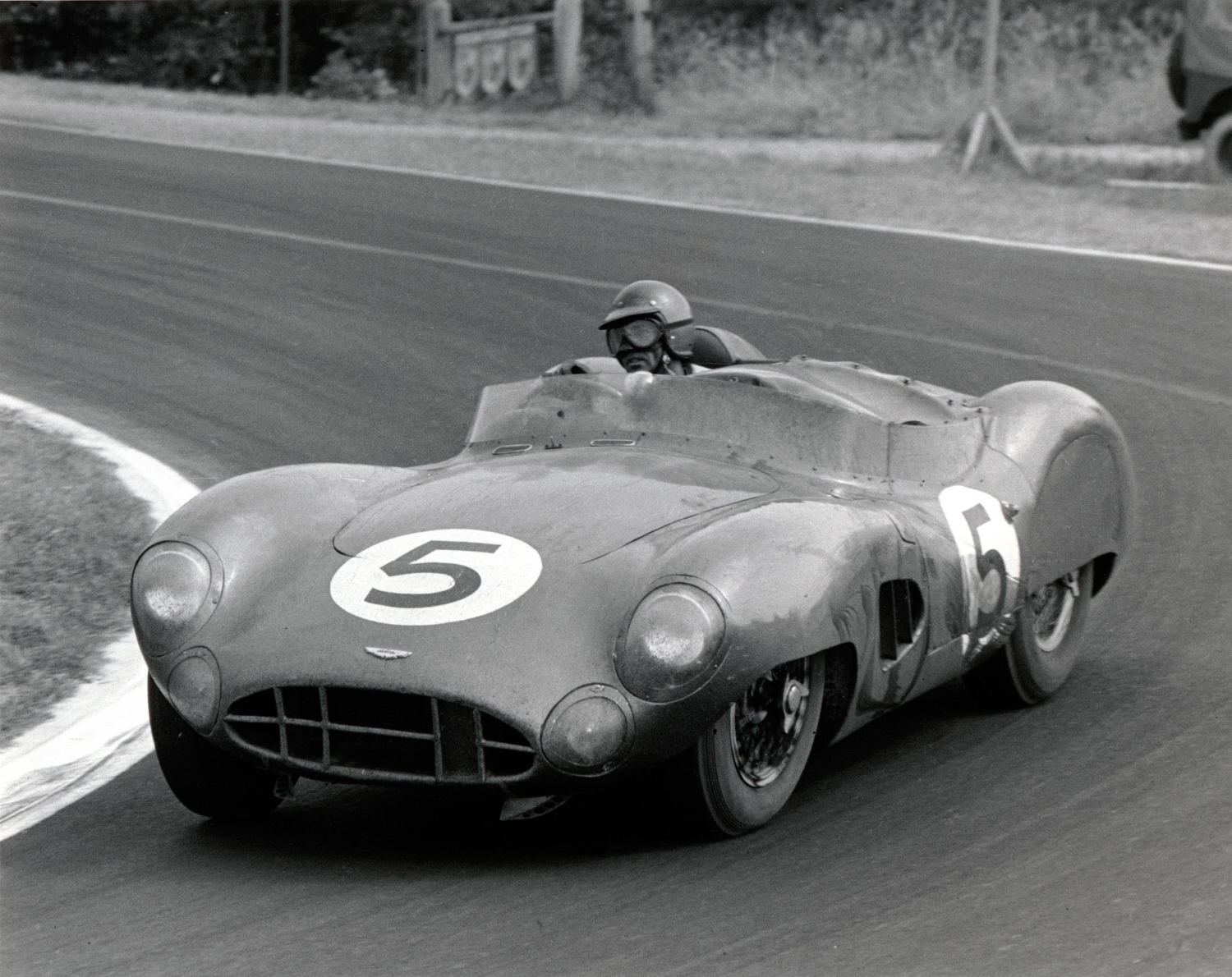

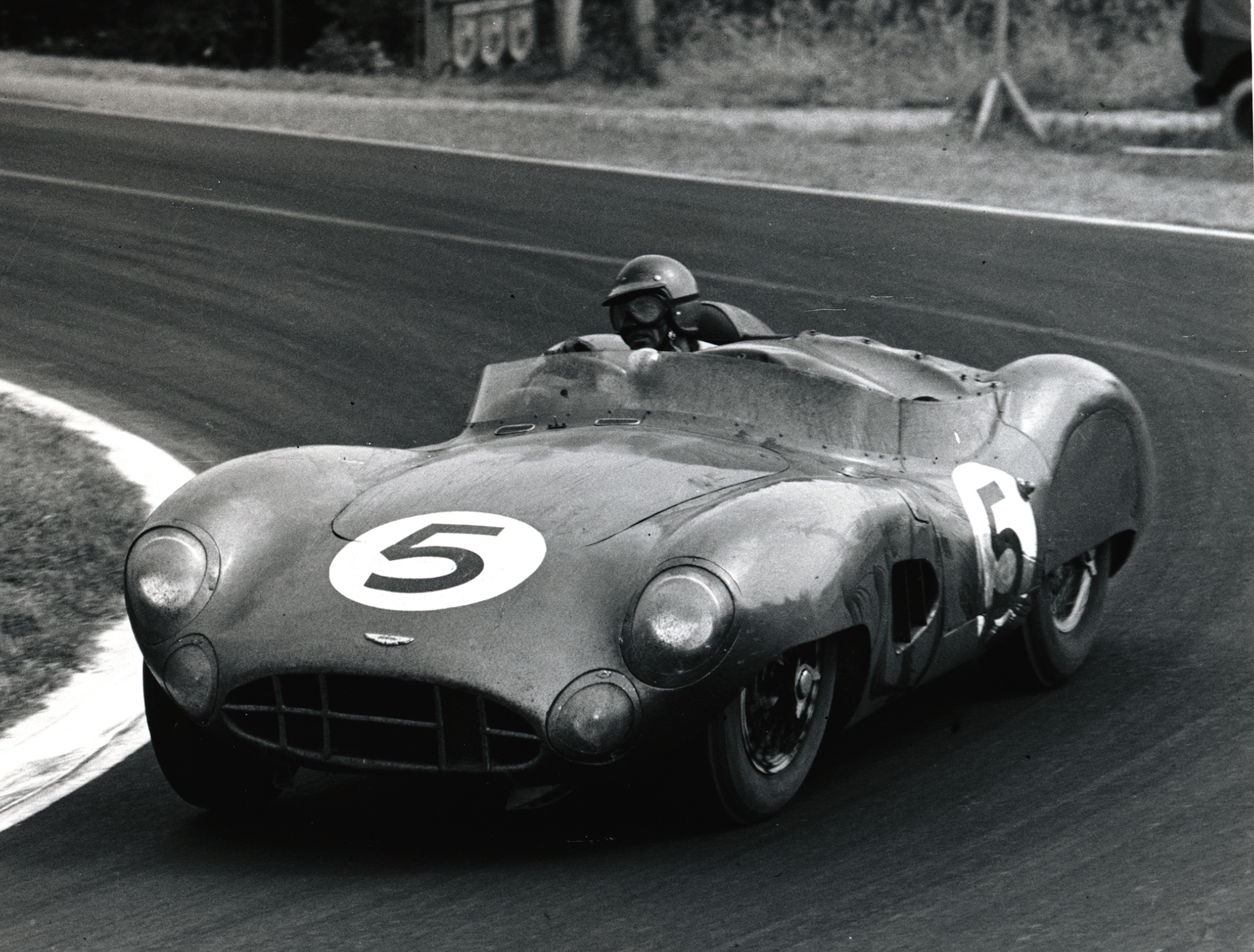

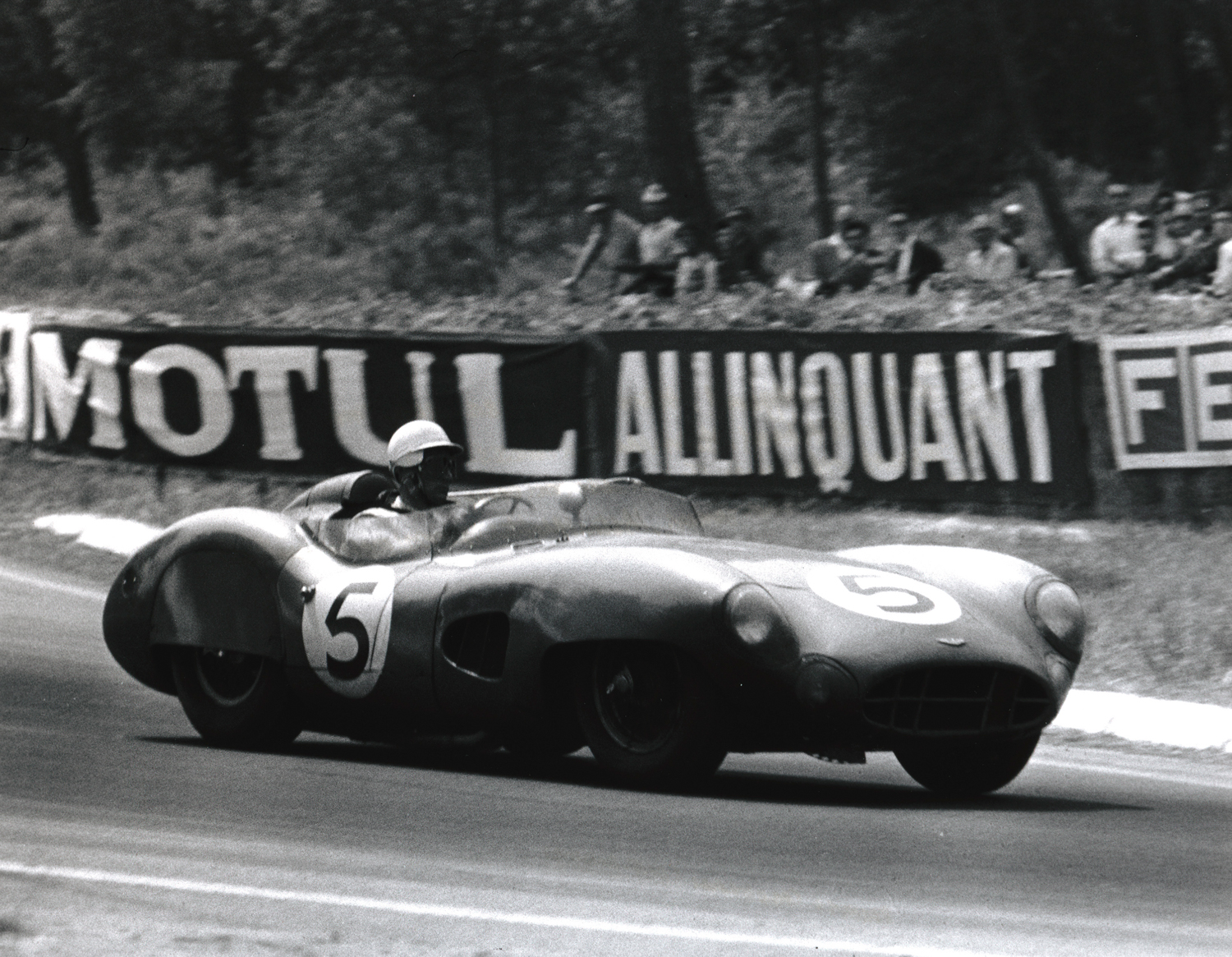

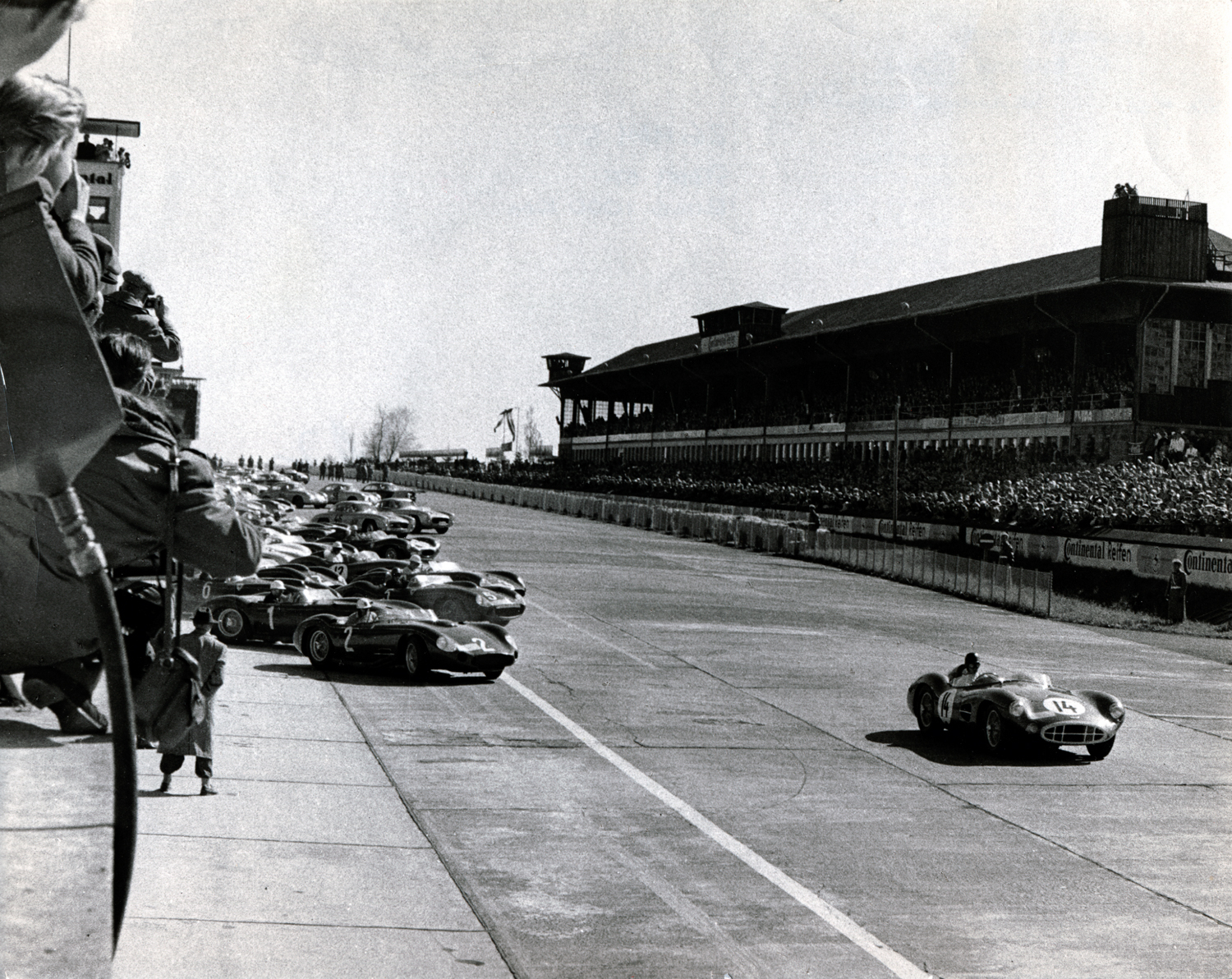

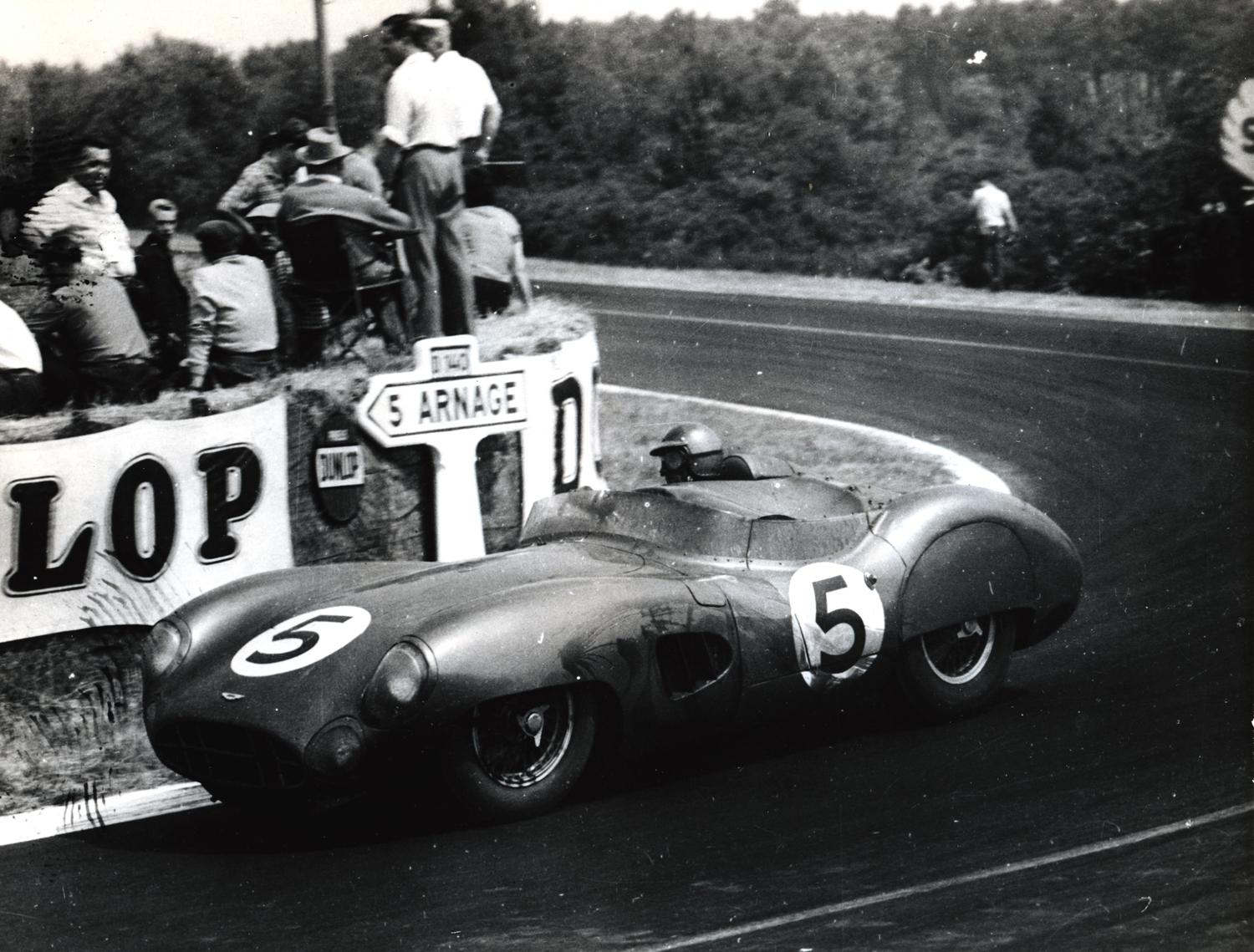

On the 26th of May 1957, English cars and a gent from Huddersfield named David Brown attained a long-sought goal. Since the war this short, bespectacled industrialist had spent hundreds of thousands of pounds on machinery to perpetuate the name “Aston Martin.” On that day he had the pleasure of watching his latest Aston racing car trample the cream of Italy’s sports machines on one of the world’s most testing road courses: the Nürburgring. His drivers were the impeccably fast Tony Brooks and newcomer Noel Cunningham-Reid, young men who had been groomed for Aston’s racing program by team manager Reg Parnell and his predecessor John Wyer, now general manager of David Brown Automobiles.

Although an all-English victory, it was important for other reasons. Since the war, Jaguars had dominated fast courses like Le Mans and Reims. Britain’s own short sprint and club races were the province of home-grown marques like Lister and Tojeiro, while Cooper and Lotus had to be reckoned with in any class under two liters. Yet through it all there was no English car that challenged the eminence of German and Italian cars in most of the world’s classic sports car races: the ‘Ring, the Mille Miglia, Targa Florio, Tourist Trophy, Mexican Road Race and Sebring.

These and similar events could only be contested by well-balanced, all-round sports racing cars on the order of the 300SLR Mercedes-Benz or 300S Maserati: not too big and not too small, with no more power than could be used and excellent suspension to keep it all on the road. Aston Martin was the only English outfit to pursue this goal sincerely. Always just on the verge, they finally made the grade that May. Their car, the DBR1/300, was a beautiful design that drew heavily from the past and pointed significantly to the future.

Thanks to the enthusiasm for good cars of David Brown himself, a keen racer in his youth, by the year 1948 the David Brown Companies (builders of Cropmaster and Trackmaster tractors, transmissions, axles, gears and gear cutters, steel castings, and once the Lucas Valveless and Dodson cars) owned the assets of both Aston Martin and Lagonda. The latter boasted little more than a respected name and a promising prototype engine designed, in 1945, by W. O. Bentley, famed for his creations during the 1930s.

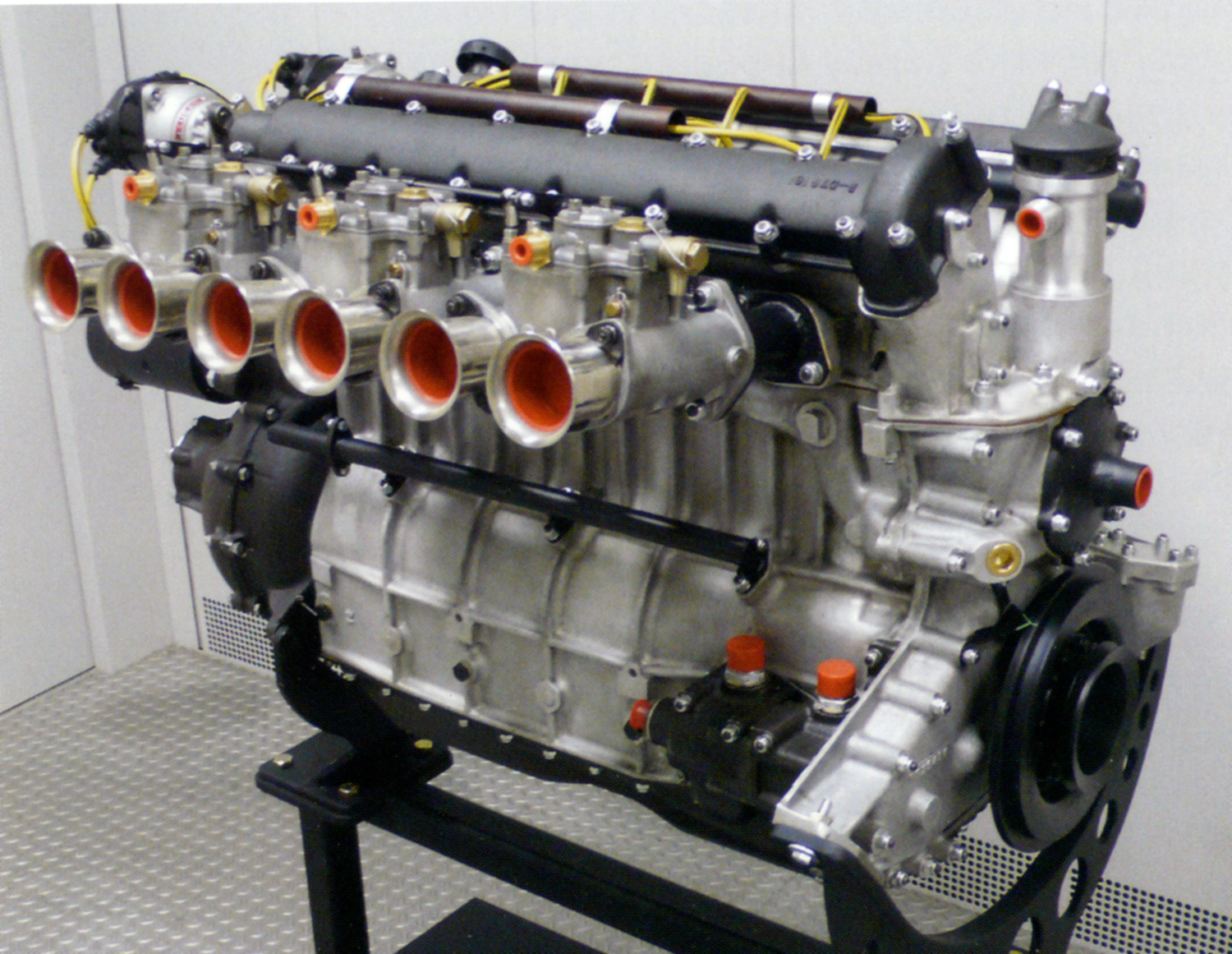

Bentley’s twin-cam 2½-liter six, the LB6, became the heart of the early post-war Astons and was still recognizably the base of the DBR1’s engine. Much heartache was endured before this latest version was worked out, however. Features of Bentley’s engine that remained in the racing Astons were the twin-overhead-cam layout, valve angle and actuation and chain cam drive. Early racing versions and production Astons had cast-iron heads with one plug per cylinder and a single water outlet between the cam cases, just as W. O. laid it out. Around Le Mans time, in 1954, the head was reworked to allow casting in aluminum alloy and to double the number of spark plugs, to be used in the competition cars only.

The cylinder head was narrow and had very short integral ports. It was deep, however, allowing a lot of water to contact its plugs, valve seats and valve guides. All the guides were wet, pressed in place and partially retained by the inner coil valve springs. Valve operation was much like that of the Jaguar XK120, with cup-type tappets shrouding the coils, but clearance adjustment was by selective assembly instead of shims. Valves were inclined at 30-degrees, either side of the cylinder centerline, giving a shallow combustion chamber and minimizing shrouding of the open valve. A feature aiding production and maintenance was the use of a common horizontal plane for the parting lines of cam-bearing caps and housings on both sides, simplifying head machining and assembly.

The water outlet system in the redesigned head was unique for a six. A tidy manifold along each side collected hot water from six oblong ports just above the intake and exhaust openings and ducted the flow forward into a tee, from which one short hose fed into the header tank. They tried two separate hoses to the header but that wasn’t the answer.

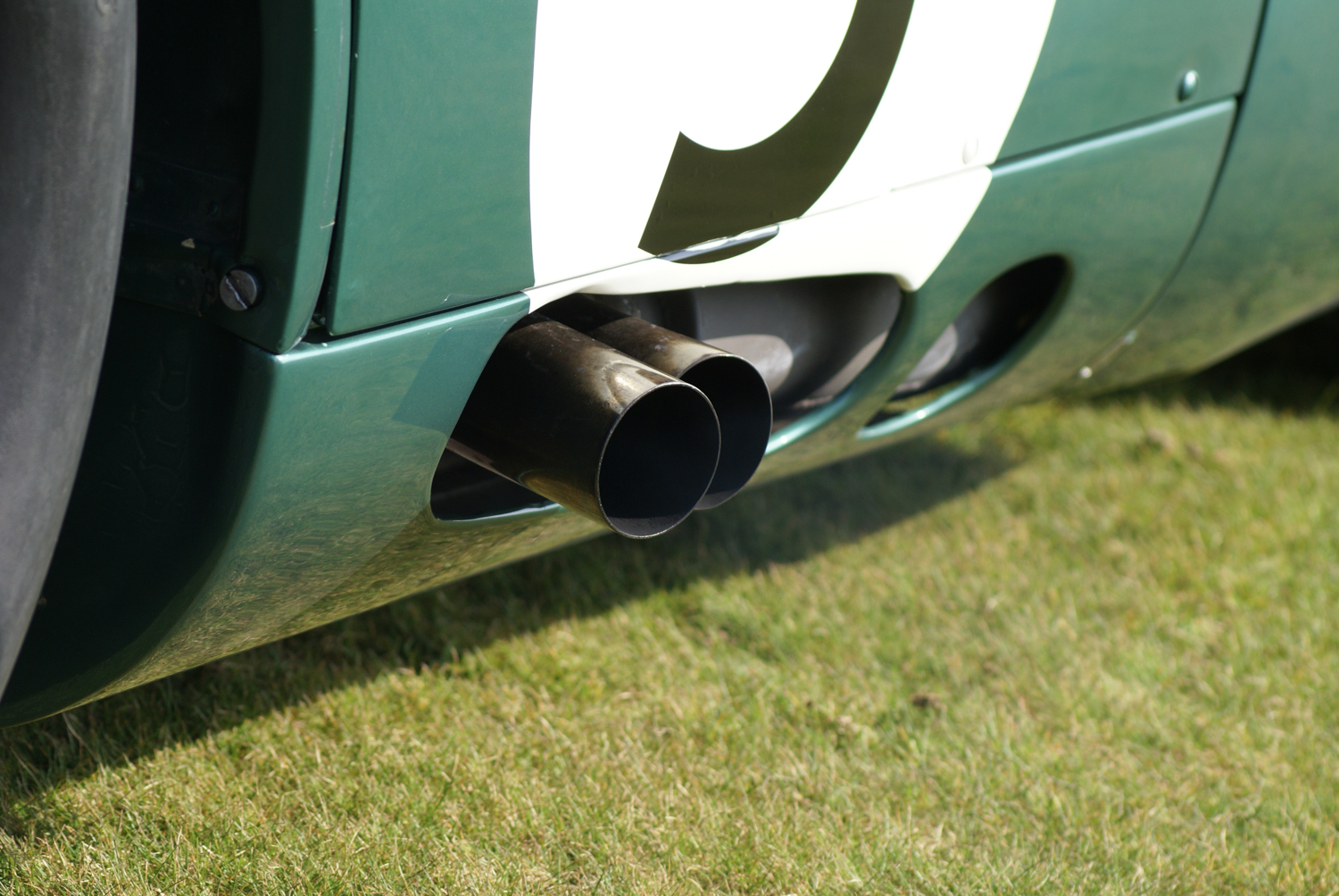

Once pioneers in the use of Solex twin-throat, side-draft carburetors, Astons were now back to the standard fixtures: Webers. Three 45-mm, double-bodied units were carried a short distance from the head by fabricated piping. Cool air came from the low snout via a flexible pipe and an alloy balance box. Exhausting was through two short, separate manifolds and twin pipes coming down through the right wing and under the DBR1’s door. Three big holes chopped down there drew heat away from the nearby driver.

To fire its 12 plugs, the alloy head included two Lucas distributors driven from the back ends of its camshafts. Most of these cylinder-head refinements were carried out on the DB3S racing Astons during 1954 and 1955. Early in the latter year, David Brown began contemplating a replacement for the DB3S. After Le Mans 1955, the go-ahead was given by John Wyer, general manager of the car division, for a new racer. Edward John ‘Ted’ Cutting was named chief designer, special products, David Brown jargon for racing engines and cars. The new machine would be his baby.

For what would be called the RB6 engine work began at once on a new aluminum cylinder block to take the existing racing head. The ex-Lagonda block-crankcase casting was barrel-type, three of the four main bearings being supported by split bearing carriers or ‘cheeses’ that were bolted together around the main journals before the whole assembly was threaded in from the clutch end of the crankcase. The W. O. Bentley interpretation demanded that the machined exterior of each circular carrier mated perfectly with corresponding interior bores. Set screws were used to locate the carriers.

When using aluminum carriers in an iron block, as in the production Astons, high temperatures and hard work caused the fit to tighten, if anything. This didn’t hold when the block was alloy too, so in the RB6 the system of using ‘cheeses’ to carry the main bearings was replaced by a conventional bottom end in which the crankcase sides came down four inches past the crank centerline—virtually as far as did the older block—so the deep main-bearing caps could be cross-bolted into the structure. A deeply ‘waffled’ exterior added stiffness to new block.

Cutting decided to use the old crankshaft forgings, which continued the use of four main bearings. The mains were 2½ inches in diameter and very wide while the 2.0-inch rod journals were nearly the same width. Just enough room was left for thin connecting webs and three big counterweights.

Bentley’s 1945 concept for the LB6 engine included a two-stage, roller chain-drive for the cams. Ted Cutting rejected this in favor of an all-spur-gear drive to the cams as well as the accessories including the oil pumps. Just as in the iron block, the water pump fed a duct cast along the top of the exhaust side of the block. This directed the coolest water where it was most needed and allowed the coolant around the cylinder liners to circulate by convection only.

Speaking of liners, they too were changed. The Lagonda design had flanges at top and bottom of the liner, which was compressed into place and sealed by the cylinder head. To relieve stress on the centrifugally cast iron wet liners, Cutting adopted Vittorio Jano’s Lancia solution. The liner was firmly clamped by a flange at the top only. The bottom end hung in an appropriate bore and was sealed by O-rings.

New to the RB6 engine, dry-sump lubrication was adopted to allow the engine to be set three inches lower in the chassis. A single pressure pump and double scavenging unit fed a reservoir set opposite the driver to balance his weight. Oil was cooled by a radiator block to the right of the Marston water radiator.

Available for consideration was an in-house fuel-injection system that had been built and tested in the DB3S. It adapted a CAV diesel injection pump to deliver petrol instead of diesel oil, along the lines of the successful Bosch injection. A huge Mercedes-style air box was riveted up, with an air valve at the front end and ram tubes to the ports. Instead of direct injection to the cylinders, as used in the German cars, injection nozzles were out in the air box and aimed down the ram tubes. Although the injected engine performed fairly well in a DB3S, the ever-reliable twin-choke Weber carburetors were retained for the RB6.

With its dimensions of 83 x 90-mm for 2,922-cc the RB6, which designer Cutting called “the illegitimate son of the LB6,” typically produced 240 bhp at 6,000 rpm. When it first raced at Le Mans, in 1956, its size was 2,493-cc with the short-stroke dimensions of 83 x 76.8-mm to suit the 24-hour race’s specifications that year for prototype cars. Delivering 212 bhp at 7,000 rpm, it took the car into fourth place, which it held until the 21sthour when bearing failure retired the Aston Martin. This was the DBR1’s first and only outing in 1956.

To contrive the original racing car to use W. O. Bentley’s LB6 engine, David Brown hired a renowned designer from Bentley’s era: Prof. Dr. Ing. Eberan von Eberhorst. First famed for his association with Ferdinand Porsche and for most of the design work on the 1938-’39 Auto Union Grand Prix car, Eberan seemed a good choice to create the DB3, Aston Martin’s competition sports car.

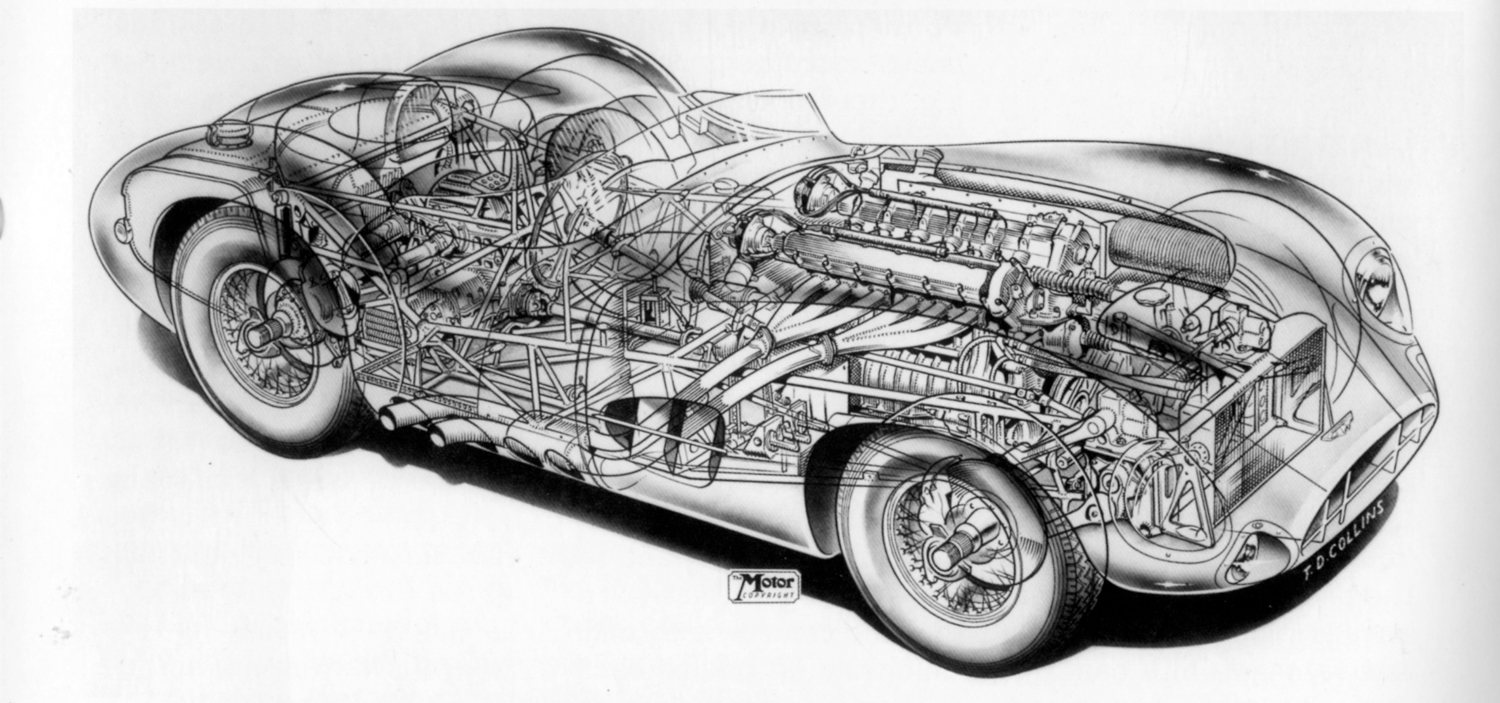

As it first appeared in 1951, the DB3’s big-tube frame, trailing-arm front suspension, steering geometry and de Dion tube location were twins to those of the Auto Union. For the DB3S, the de Dion placement was changed from a Panhard rod to a vertical slide to eliminate snaking on bumpy straights. The same advantage with less friction was given by a Watt’s linkage on the new DBR1/300.

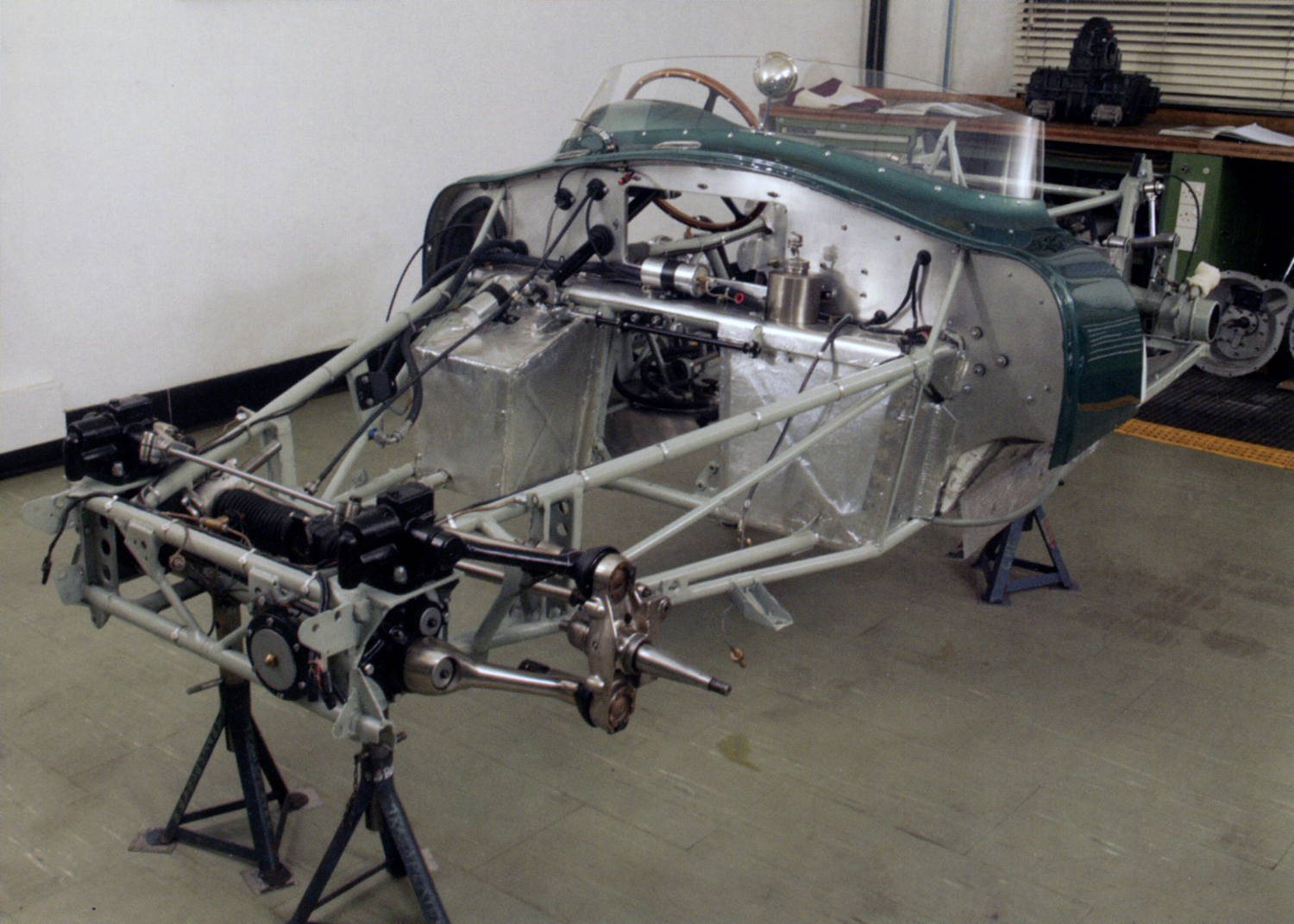

Rear suspension on the DBR1 was entirely new and well worked out by Cutting. A two-piece de Dion tube was bolted together at its center, forming a “V” behind the final drive unit. Hubs and most other fittings were welded up of light sheet stock. Parallel trailing arms on each side guided the hubs, working in wide rubber bushes. Lateral location, as mentioned, was by a Watt’s linkage, with the vertical member straddling the axle tube in the center and the guiding rods extending to each side of the frame. The suspension’s torsion bars were aligned longitudinally instead of laterally, where they would have fouled the new rear-mounted transaxle.

The DB3S front suspension and steering were carried over to the DBR1, taking advantage of the improvements made by Eberan since his days with the Auto Unions. One problem in that pre-war era was change in camber under heavy braking, thanks to weak upper trailing arms. Eberan’s Aston design—with triangulated upper arms whose branches embraced lever-type hydraulic dampers—was the perfect answer. A thin torsion anti-roll bar connected those arms at the pivots.

The bottom trailing arms, single but heavier, turned in two big needle-roller bearings each and were connected by spherical blocks to transverse torsion bars. To fit these in they had to be crossed, with each anchor above the opposite pivot. A single casting at each side took all the stresses from arms, shocks and anchors and fed them into the chassis through six bolts. This structure, and its ball-jointed steering knuckle, was unchanged after six years. However, Ted Cutting made alterations in materials to reduce weight.

The DBR1’s steering made use of a rack-and-pinion gear and a two-piece track rod. As on the Auto Unions, this brought precision and simplicity at the price of mild wheel fight in bumpy cornering. The wheelbase was three inches longer than that of the DB3S at 90 inches while track was the same at 51½ inches. Dampers were Armstrong tubulars, placed well behind the hubs.

Cutting replaced the two big frame tubes favored by Eberan with a multi-tube space frame that followed the successful example of the latest models from Colin Chapman’s Lotus, rather than the ultra-complex Mercedes-Benz designs. He used chrome-molybdenum steel tubes with diameters of 1.0 and 1.25 inches depending on their locations. The designer admitted that “by the time the brackets to hold the major components etc. were added the weight saving was not so great as anticipated.” Dry weight was 1,800 pounds with 60 per cent on the rear wheels over the range of fuel-tank capacity.

Just aft of the front suspension on each side were two engine mounts, welded to drilled pillars, which when married to the block added frame strength. At the center of the firewall was a rectangular opening, into which a separate clutch-housing casting was bolted at three points. A group of studs spaced on the back of the block in the shape of an inverted “U” attached the engine to this casting. The clutch proper was a small-diameter, dry, multiple-disc unit developed for racing by Borg and Beck. The starter motor protruded to the rear above the drive shaft. Torque and engine rpm were carried back by a conventional Hardy-Spicer prop shaft.

As David Brown Industries were in the transmission business in a big way, the post-war Aston Martin gearboxes were always handsome in appearance and smooth to handle. Perhaps due to unfamiliarity with operating conditions over a rev range double that of commercial vehicles, however, some of the racing gearboxes and final drives had not been fully reliable. There had also been much variation from car to car.

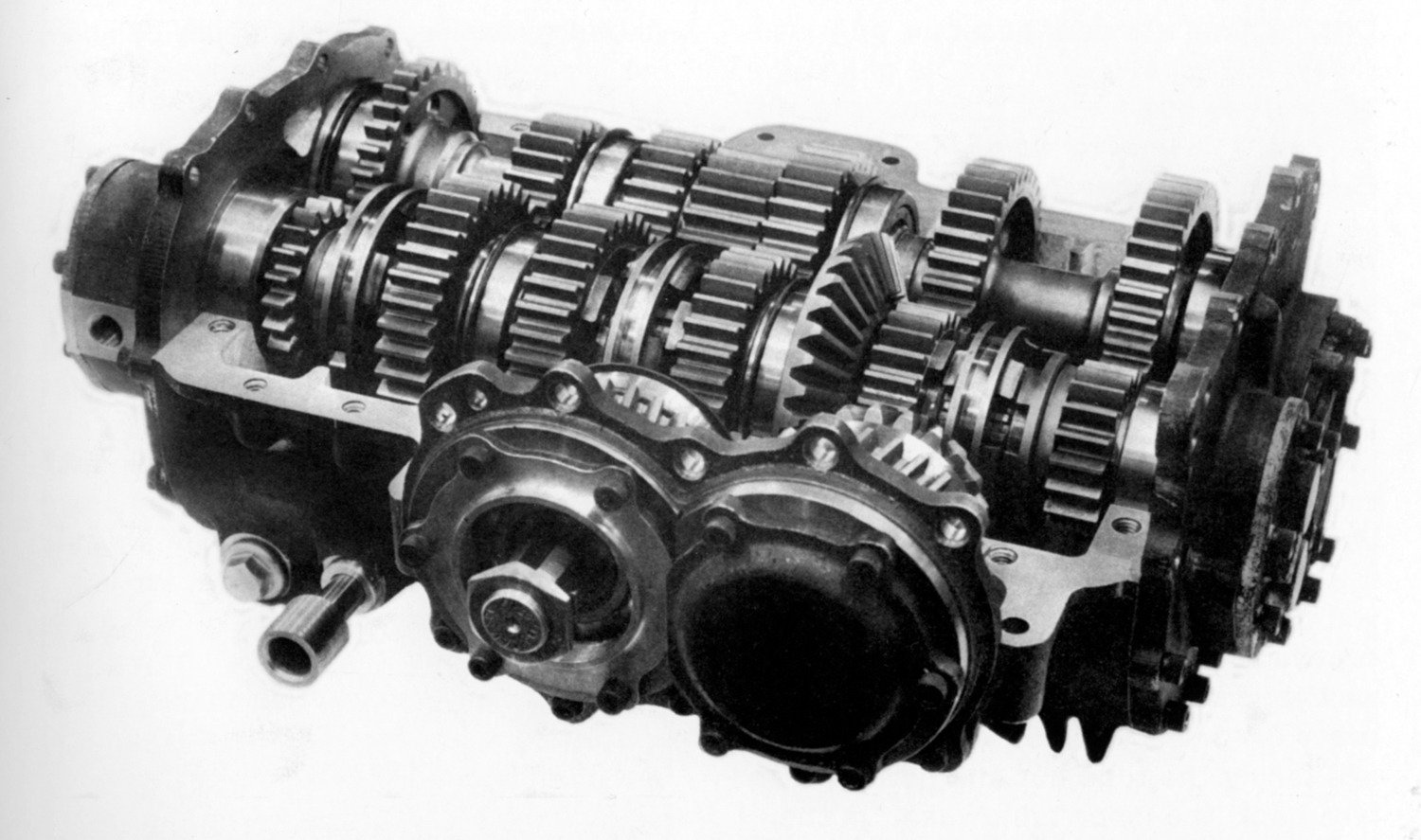

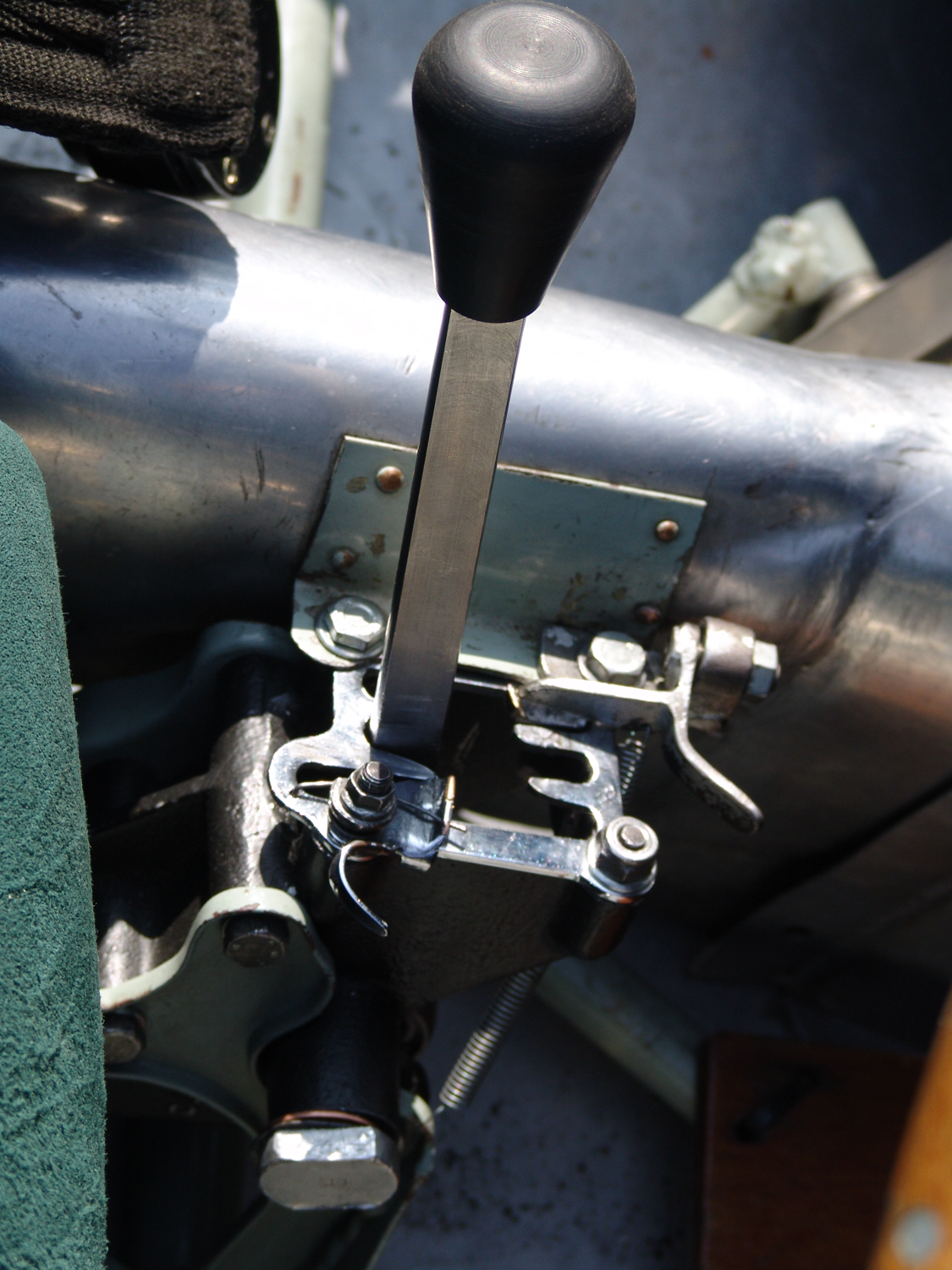

The DB3 had a synchronized five-speed transmission laid flat, in unit with the engine, and a hypoid final drive. With but four speeds and synchromesh, the DB3S box was arranged vertically and drove a spiral-bevel gear set. Now, the DBR1/300 appeared with five constant-mesh spur-gear ratios selected by dog clutches and a general layout reminiscent of the 1937 Mercedes-Benz W125 final drive.

This was the CG537 transaxle from David Brown. Drive from the prop shaft entered through a helical pair of gears at the front that could readily be changed by removing the Allen-head cap screws and cover plate. Ultimately six different ratio sets were available, which with two choices of final-drive gears gave a choice of overall ratios from 2.78:1 to 4.75:1. The two gearbox shafts were placed across the chassis with the primary shaft to the front. It was driven by a straight-toothed bevel set and carried all the dog-clutch selectors.

There were three cavities in the case and four bearings for each shaft, made possible by case separation on the shaft centerlines. First and second gear sets were on the left while third and fourth—most commonly used—were in the center, embracing a spur takeoff to the ZF differential above. Overdrive fifth and reverse were in the right-hand section. The shift rails were interlocked with a valving system which directed oil under pressure only to those gear sets that were under load.

Although the CG537 transaxle was conceived as a wet-sump assembly, Ted Cutting asked that it be reworked as a ‘semi-dry’ unit. An added scavenge pump delivered oil to a one-gallon reservoir through a gilled-tube cooler in the right rear wheel well. Hung from one point high in the front and two lower down in the rear, the transmission contributed to the frame’s stiffness. Fully machined half-shafts had Hardy-Spicer universal joints and splined couplings.

Moving the hefty five-speed gearbox to the rear was in accord with the latest thoughts on weight and mass distribution—with which Eberan von Eberhorst did not fully concur. Without fuel, which was stored right in the tail in Gallay tanks, the DB3 and DB3S had about 56 percent of their weight on the front wheels. This gave them a basic understeer. But due to a low polar moment of inertia (engine in unit with gearbox, placed well back) these models were still oversensitive to control in some high-speed situations. A dry DBRI/300 now had 52 percent of the weight carried at the front and a much higher polar moment of inertia. Thanks to this and its lowered center of gravity it handled better than its predecessors, especially on fast bends like those at Spa.

Always faithful to Girling, Aston Martin waited until 1955 to adopt disc brakes. Since then its simple single-spot calipers had been used exclusively. In ‘56 they were modified to allow 45-second replacement of the thick Ferodo pads. At first on the DB3S specially offset Dunlop wire wheels were required to leave room for the discs and calipers, but for the DBR1 Borrani wheels were specified. For some time Astons had enjoyed the complete attention of the Avon Tyre Competition Department. Avon served only Aston and Astons used no other tyre.

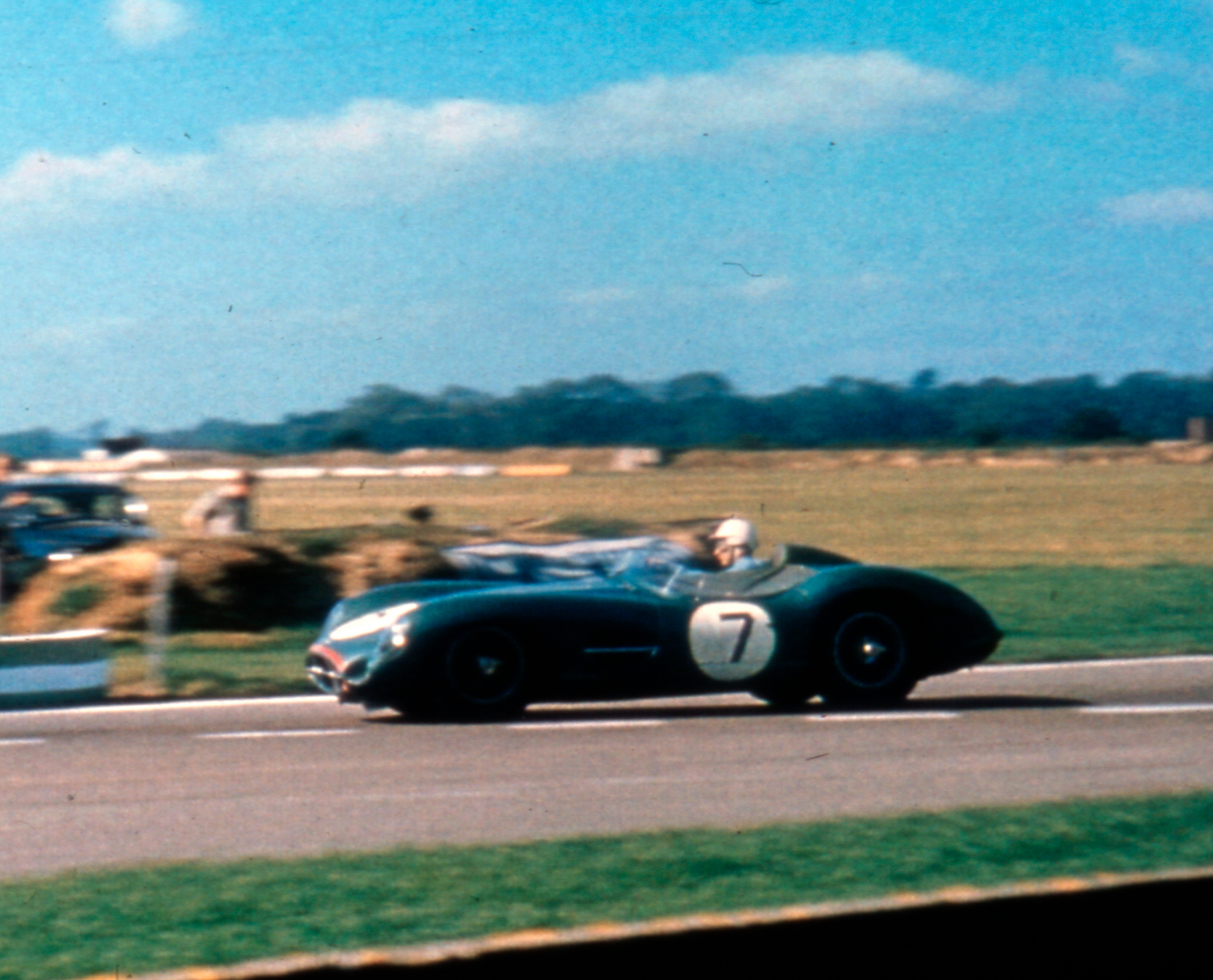

Both before and after the war good looks were an attribute of Aston Martins for both road and racing and the DBR1 was no exception. Body designer Frank Feeley received credit for many jobs well done. In this instance, however, the shape was Ted Cutting’s—and a lovely job it was. He was assisted by body draftsman ‘Steve’ Stephens. A false step was the front end of the 1956 Le Mans prototype DBR1/250, but the 1957 version was a handsome sports racing car in the Aston tradition.

The shell of the DBR1 was pounded out of aircraft-quality aluminum alloy sheet and hung on a light tubular framework. Dzus fasteners were used wherever practical, such as sections of the belly pan. All the body shapes were functional except for one quirk that managed to attract water from the wheels into the cockpit on a wet track. Smith instruments festooned the typically English dash, featuring a huge 8,000 rpm tachometer and smaller dials for charging, water and oil temperatures and oil pressure. Pivoted from the floor, drilled brake and clutch pedals were bracketed by the accelerator and a ‘dead pedal’ for bracing the left leg.

The 1957 season that began so well for the DBR1/300 continued for Tony Brooks with a win in the 359-mile Grand Prix of the Belgian Auto Club against non-works opposition. Le Mans saw both cars retire, which was repeated at Sebring in 1958. Nor did a car for Moss and Brooks—a wonderful pairing—survive the 1958 Targa Florio. Although Moss set a new record for the circuit on his fourth lap, his Aston retired with gearbox problems, Brooks never getting a chance at its wheel.

In the meantime, development had continued on a cylinder head designed by Willie Watson with greater airflow potential. Watson took a classical approach with extremely steep valve inclinations of 45-degrees from the vertical for the inlets and 50-degrees for the exhausts, a total of 95-degrees.

“It had a combustion chamber just like a short, fat sausage,” Ted Cutting recalled, “cut in half horizontally. At each end was a valve and the two spark plugs were in the very short cylindrical bit at the middle.” This attempt to induce some squish and swirl into the mixture failed, Cutting said, “so we modified it by machining a cone into the chamber and making it into a close approximation of a straightforward hemispherical head.”

Of aluminum, the 95-degree head was fitted with cast iron and bronze guides for the inlet and exhaust valves respectively and carried the camshafts direct without bearing shells. The new head was first raced at Spa in August, 1957, giving a useful power increase over the 60-degree head and, by 1958, the Aston team sports cars were regularly using it. When fed by 50DCO Weber carburetors with 40-mm venturis and a 9.8:1 compression ratio it delivered 255 bhp at 6,000 rpm and 235 lb-ft of torque at 5,400 rpm.

The Nürburgring, in 1958, was again a happy hunting ground for the DBR1/300. This time the star was Stirling Moss with Jack Brabham on hand for mid-race relief. Number one on the car was number one at the finish, with the brilliant Moss making up for the lesser pace of Brabham, who had little practice time in the car. Though three Aston entries failed at Le Mans, three entries placed 1-2-3 in the 355-mile Tourist Trophy at Goodwood. In what Motor Sport called “a high-speed demonstration” against negligible opposition the Moss/Brooks car won against Salvadori/Brabham second and Shelby/Lewis-Evans third.

For the 1959 season—the second in which a three-liter limit for sports racers played into the hands of Aston Martin—an enlarged bore of 84 mm brought the engine’s capacity to 2,992-cc. For reliability Ted Cutting strengthened the block and fitted seven main bearings. Connecting rods were a new, deeply‑webbed pattern. Fully machined from forged blanks, they effected a 200% increase in strength at the sacrifice of one more ounce of weight. Full‑skirted Hepworth and Grandage pistons carried one oil ring each and two narrow Dykes compression rings a respectful distance below their steeply peaked crowns.

In 1959, Aston Martin repeated its ‘58 victories in the Nürburgring 1,000 Kilometers and Goodwood Tourist Trophy. At the ‘Ring Stirling Moss’s mid-race co-driver was Jack Fairman, who like his predecessor could not manage the Moss pace and, even worse, put the car off the road. By “sweating blood” he got it back to the pits—to the relief of team manager Reg Parnell—where a refreshed Moss set about catching two works Ferraris and setting new sports-car lap records. At Goodwood, both Moss and Fairman shared the winning DBR1/300 with Carroll Shelby, their pit stops speeded up by installing an on-board jacking system.

In search of more straight-line speed at Le Mans, a quarter-scale model of the DBR1/300 was tested in the Cranfield Aeronautical College’s wind tunnel. As a result the cars for the 24-hour race had raised rear decks, shrouded front wheels and spats over the rear wheels. These brought from 7 to 10 more miles per hour on the Mulsanne Straight, even though the added internal friction of the seven-bearing 1959 engine meant that it was slightly less powerful than its four-bearing forebear.

After failures at Le Mans three years running for the DBR1 design it came good in 1959. Three cars were entered, Moss being designated the hare to break up the opposition. This he did effectively, a leading Ferrari retiring, before his own retirement. Next fastest Aston was that of Roy Salvadori and Carroll Shelby, who were obliged near noon on Sunday by retirement of another Ferrari that left them in the lead to the finish. Backing up the win were Maurice Trintignant and Paul Frère in second place, a lap behind the winner.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1iagFDIjosI

This epic success was not only deeply satisfying on its own but also a contributor to the points total that made Aston Martin the World Champion of Makes in 1959. This marked the achievement of key goals that David Brown had set for his team. On the recommendation of John Wyer, who saw merit in quitting while ahead, Brown approved the withdrawal of Aston Martin from works sports car participation after the 1959 season.

In 1960 and ’61, the cars were in the hands of private teams. One of the latter was the Border Reivers outfit, which was moving up from Listers and Lotus Elites. In its Aston a young Scot named Jim Clark was in his third major season of motor racing. He and Salvadori placed third at Le Mans in 1960 in their DBR1/300, a car of quality nurturing the career of a driver of quality. It was a fine legacy for the best racing car that Aston Martin had yet built.