South Africa has a rich motor racing history, and during the 1930s a number of International Grands Prix were held at major centers around the country. Whitney Straight won the first South African Grand Prix in 1934, and later visitors included the Auto Union team with such greats as Bernd Rosemeyer and Ernst von Delius, official Maserati teams and hosts of English amateurs with ERAs and Rileys. Sadly, World War II put a temporary end to this, so racing had to wait until the late 1940s to resume.

Motor racing quickly revived and became popular after the war, but racing cars were a scarce commodity. There were a number of interesting pre-war, factory-built racers that had found their way to the tip of Africa, but in the main, racing enthusiasts had to make do with what they had, could find, could afford, modify or make. Even when specialist racing cars were available, import restrictions for those who had the wherewithal to buy such “proper” racing machinery discouraged the acquisition of these factory-built machines.

Servicemen returning from the war and immigrants from Europe brought with them new skills, and innovative and ingenious “specials” began to be developed by resourceful amateur enthusiasts. The existing, much-raced old cars were recycled, cannibalized or converted, and some of the pre-war factory cars were also modified to take less exotic engines.

Racing took place on “makeshift” tracks, either on old airfields or public roads that had been cordoned off.

A bewildering array of machinery began to gather on the starting grids around the country. There was no engine size restriction and so single-seater, factory-built racing cars, homebuilt specials, sports cars and, in some cases, even cut-down and lightened sedans made up the fields. Because of the rich diversity of cars taking part, the championship events were run on a handicap system.

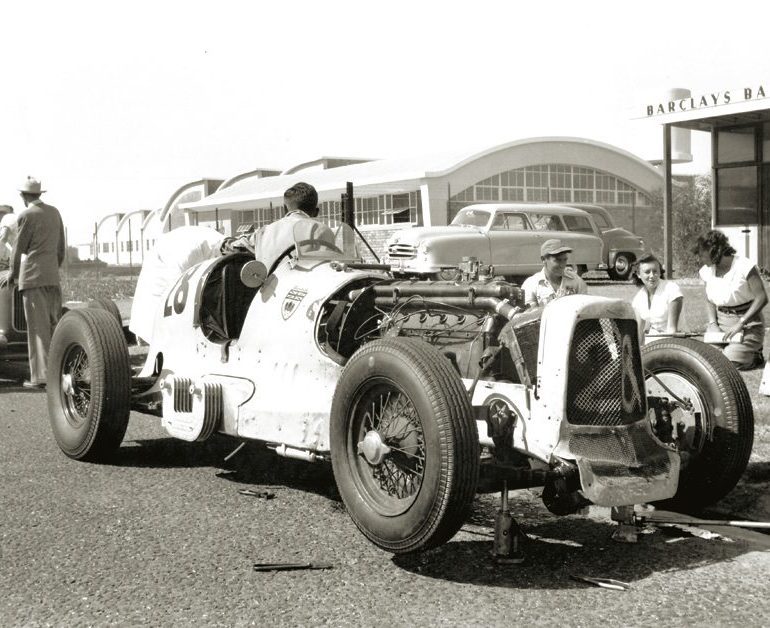

It was in this somewhat relaxed and sporting racing environment that gentlemanly John Gurney Hanning decided to take up the sport in late 1953, at the age of 41. He acquired a pre-war Aston Martin Ulster chassis that had been fitted with a 230 cubic-inch Nash Ambassador engine. The car had been owned by Peter Burroughs, an accomplished performer and, while not one of the outright fastest machines, it was capable of running “nearer the front of the field.”

John came from a well-to-do British Quaker family, the Aggs, and during World War II had served as an officer in the “Ack Ack” battalion.

After the war, John and his wife Hazel settled in Cape Town and John took up a position with a leading financial institution in an accounting role. Hazel—who from the age of five had helped her father, an amateur racing driver—considered herself a “good mechanic,” and so the Hannings joined the Cape-based Amateur Automobile Racing Club.

“As there was very little money involved, everyone helped everyone else. We were a happy lot of enthusiasts,” recalled Hazel.

Hazel noted that John had “dabbled” in racing at Brooklands before the war. “It was before I met him, but he had a friend who had an MG of sorts and they raced on Saturdays; but they didn’t do any good.”

The Ulster, in its original form, had been imported into South Africa by Billy Mills during 1937 and competed in the pre-war Rand and South African Grands Prix, but a succession of owners had resulted in the car being modified, with Hudson and Studebaker power plants being used at various times. Neville “Lofty” Wood, an inventive engineer and gifted mechanic, was the service director at Robbs Motors, the Cape Town dealership responsible for Rolls-Royce and Jaguar and had installed the 6-cylinder Nash engine in the Aston Martin for Burroughs, that “came with the car” to the Hannings.

Initially, Hazel took on the role of mechanic and assistant, and her daughters Judy and Jane became enthusiastic helpers while Neville concentrated on modifying and developing the car. One of Hazel’s first tasks was to redesign the bodywork, which resulted in a menacing-looking vehicle.

Those who knew her well describe Hazel as an intelligent and practical engineer, who besides her expertise with racing cars, carried out many clever building innovations in the construction of the magnificent family home near Cape Town.

Amazingly, this powerful out-and-out racing car was licensed for road use and was driven to the tracks by John or Neville. In a large country like South Africa, the distances between the various racetracks in the major cities, where the big championship events were staged, entailed trips of up to 1,000 miles at times, a lot of the journey being on the corrugated surface of dirt roads. Hazel would follow the racecar in her Nash sedan, its trunk packed with tools and spares.

Neville Wood recalled travelling to the race meetings: “The racecar was too difficult to tow, so we registered it in Stellenbosch, a wine farming area, where the authorities were fairly reasonable about such things in those days. It had no mudguards or any such paraphernalia. On the untarred roads between the big cities we had to cruise at about 80 miles an hour to handle the corrugations. If we had travelled at 35 miles an hour the car would have shaken to pieces.”

Besides being mean-looking, the Aston Nash was very “hairy” to drive. The late Frank Hoal, himself an accomplished racing motorist of the 1950s and one of South Africa’s foremost racing historians, told me that he had been very impressed with John’s driving prowess.

Said Frank, “This was not so apparent at first with the Aston Nash, which was a real handful; and, of course, John was still cutting his teeth.”

During the 1954 season the new “part-timers” acquainted themselves with the somewhat serene racing environment that was based on a handicap system due to the large variety of cars making up the fields, but in the two “championship” events they contested, the car was a non-finisher.

In 1955, they achieved some encouraging results with two 5th places and a 6th place overall in major events. Importantly, the hybrid Aston Nash was matching lap times of some of the fastest cars and most experienced drivers in the large 30-car-and-more fields, but still ran a few seconds off the pace of the top contenders.

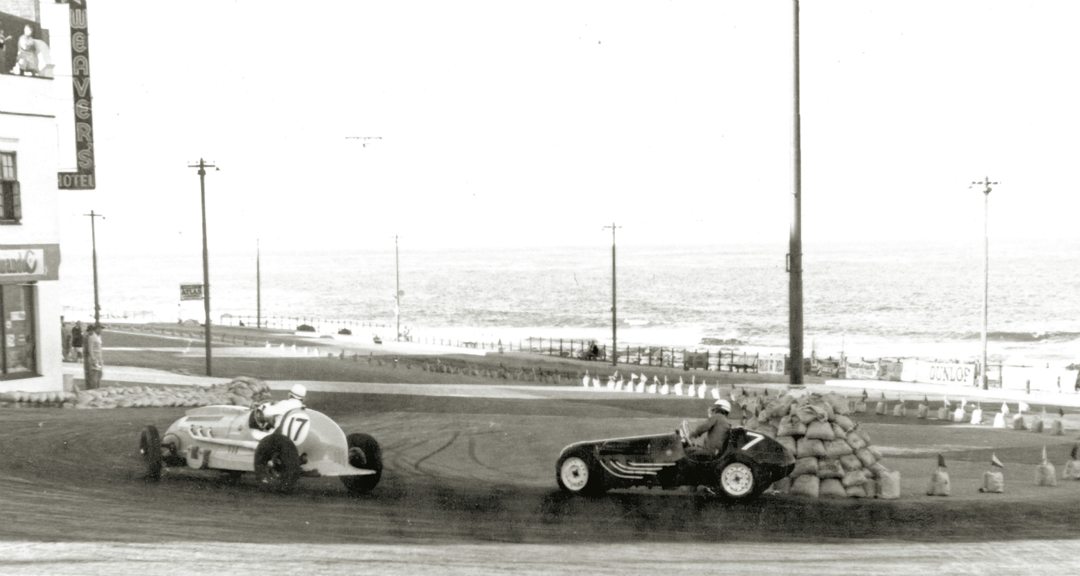

The mechanical and tuning skills of Hazel Hanning and Neville Wood were starting to bear fruit. In the False Bay 100 staged on January 2, 1956, at Gunners Circle (a makeshift track of some three miles around an industrial complex), in a field of more than 30 cars John brought the hybrid home in 9th position after some minor troubles, but his lap times at an average speed of some 87 mph were bettered only by Bill Jennings, in the championship-winning Riley Special, two Cooper-Bristols and a recently imported factory-built Cooper-Norton.

Later that year, the wealthy British privateer Peter Whitehead brought a Ferrari 625 to southern Africa for an “International” series of races, and was joined by British amateurs Bill Holt and Mike Young with A-Type Connaughts. John participated in the series, and in the Cape Grand Prix, run on the hazardous Gunners’ Circle, his promising run was cut short by bearing trouble at half-distance of the 140-mile race.

Two weeks later after a trip of some 900 miles, at Palmietfontein, a circuit carved out of an old aerodrome near Johannesburg, the 6-cylinder Nash engine strutted its stuff and with the “hairy” car suited to the wide open spaces of the airfield, he finished 8th overall in a field of nearly 50 starters. The Aston Nash proved to be as quick as several of the top local runners, and comfortably outpaced the horde of new 2.6-liter Austin-Healeys that took part in the race, but in the end Whitehead was a comfortable winner.

Hazel recalls, “John should have been 5th, but toward the end of the 150-mile race an external oil feed pipe to the rockers broke. It was a terrible mess and the car and driver were covered in oil. The pipe, which John had taped to the radiator hose, broke due to vibration.

“By then our engine modifications had made the car too fast for its brakes. They tramped so much that they were almost useless and John had to slow down very early for the bends, so Neville robbed some parts from a scrapped 1939 Buick and we converted the racer to hydraulic brakes. It was quite a sophisticated modification for the time, and we had twin master cylinders and adjustment for the back/front differential. Neville also made up anti-tramp cables to the front axle using 1947 Studebaker handbrake cables.”

After travelling over 1,000 miles to Pietermaritzburg for the traditional Natal Easter weekend racing, Hanning won the prestigious NMSU Invitation Handicap on Easter Saturday from a large field on the tight and twisty Roy Hesketh Circuit. On Easter Monday, however, the Nash expired while running near the front of the field in the championship race.

The change to A90 power was not without problems, however. Neville: “The problem with the A90 was that if driven hard it had a tendency to strip the teeth on the oil pump gears and it lost its oil pump and ignition. Engineering principles allow that if you have a skew gear you must make a hunting tooth. This will alleviate damage on one tooth that has picked up a blemish and stop it getting worse. So you should never have the same amount of teeth on one gear as you have on the other. But this principle was not used on the A90.”

To improve lubrication, they made up a little copper pipe from the oil pump delivery that sprayed a jet of oil onto the meshing gears. They found that it had little effect on the oil pressure but the modification solved the gear-stripping problem.

John then made a trip to Italy and returned with three 45 DC03 Weber carburetors. After the A90 cylinder head was skimmed to raise compression, the case inlet manifold used to take the original Zenith carburetor was machined off and the Webers fitted. The car in this guise became known as the Austin Martin, but during 1958 and 1959—although the team competed in a number of events—the car became outclassed and Hazel was disappointed that the Austin-engined car was very little quicker than when the old Nash was doing its sterling service.

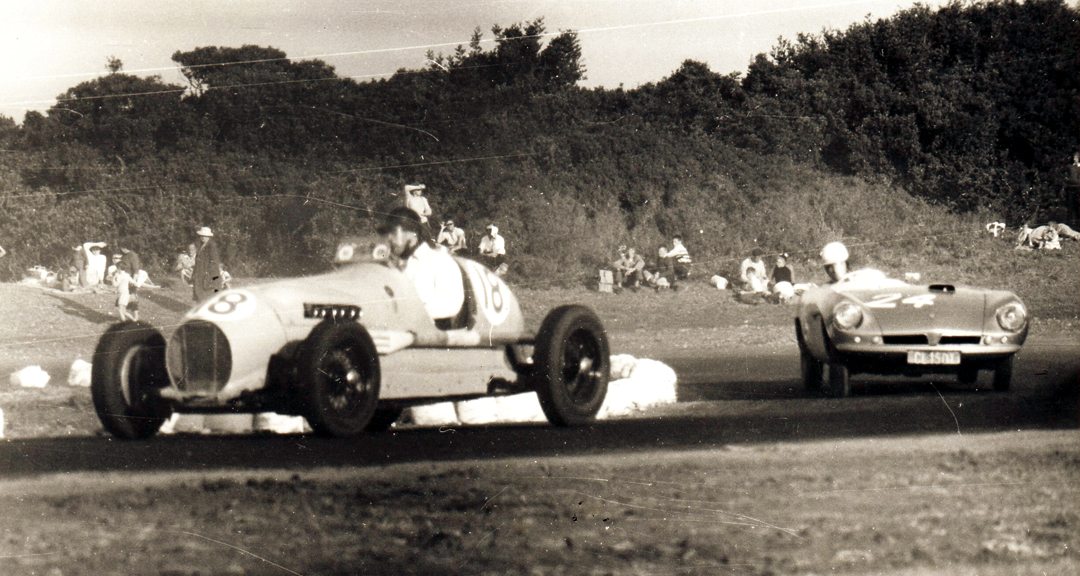

By this time there were some very “sophisticated” racecars appearing on the local scene, such as Sam Tingle’s ex-Dick Gibson Connaught, a pair of Cooper-Bristols, Syd van der Vyver’s new rear-engine Cooper T43-Alfa Romeo, the ex-Ecurie Kiwi Cooper T41s with single-cam, 1100-cc Climax engines, the Porsche 550 Spyder of Ian Fraser Jones, John Love’s Jaguar D-Type, a Ferrari Vignale Spider and Lotus 11s to name a few.

These modern, better suspended cars handled a lot better than the antiquated semi-elliptic leaf-sprung chassis of 1936 vintage, so despite its extraordinary evolution, the basic car was some 25 years out of date and it was decided that an all-new car was needed. In addition, the days of the old handicap system were over and scratch racing was the order of the day. Moreover, the country was abuzz about a coming Grand Prix, and there was talk that Stirling Moss would be invited to participate.

There were also plans to construct new purpose-built race tracks in the major centers, and the South African Grand Prix at East London would be held on a proper circuit and not the daunting beachfront Esplanade that had claimed so many lives.

Through Neville’s contacts in the motor industry a brand-new, but out-of-production, Austin-Healey 100/4 chassis was acquired and the A90 engine fitted. The chassis was “sawn-off” at the rear to make way for a fabricated rear end and Hazel designed the car’s independent rear suspension. An Austin Gipsy differential with a 4.1:1 ratio was installed and mated to an MGA twin-cam prop shaft, while Gipsy universals and halfshafts were fitted. That Neville was working for the Leyland agents explains the use of brand parts as the discounts obtained were an important consideration. Hazel described the Gipsy as a “Land Rover-type thing.”

The top wishbones were fabricated from boiler tube, while the lower wishbones and torsion bars came from a Riley 1.5. The radius rods were made from Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud track rods. Girling disc brakes were used, and calipers purloined from a crashed Triumph TR2 were fitted all round. A steering rack from a wrecked Peugeot was cut and shortened to fit. The outriggers of the Healey chassis were hacked off, leaving a slim X-braced frame onto which a single-seater body could be attached.

Hazel remembered: “We had an early plastic model kit of a Maserati 250F. Plastic was something of a novelty in those days. We based the body on it and I did the design with a little help from some university students. Len Colver, an absolute wizard with metal work built us a body in aluminum. We called our new car the Austin Monoposto.”

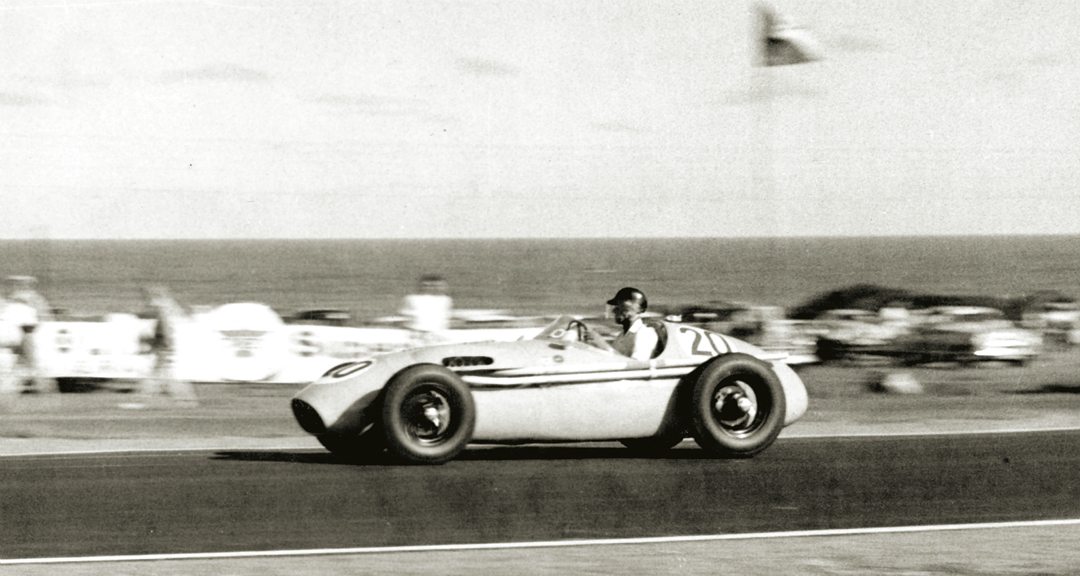

The car debuted in the 80-lap Formula Libre South African Grand Prix on January 1, 1960, at the purpose-built 2.4-mile East London race circuit, and race fans flocked to the track to see a lineup of 24 cars. The entry was headed by Stirling Moss and Chris Bristow in F2 Cooper T51-Borgwards, the Ecurie Nationale Belge Climax-engined T51s of Paul Frére and Lucien Bianchi and older Cooper T43s and T45s driven by privateers, but there was plenty of variety in the form of John Love’s D-Type Jaguar, Tony Maggs (Tojeiro-Jaguar), the Porsche 550 Spyder of Ian Fraser Jones, a Lotus 16 and a few local specials.

First time out the Monoposto was no less than 10 seconds a lap quicker than the old Austin Martin on the previous visit to the circuit, and John qualified 22nd. Although already outdated compared to the new generation rear-engined single seaters, the turquoise machine was immaculately prepared and a tribute to the Hanning team that had constructed it in their spare time, financed it privately and were using a modified passenger car engine, running on passenger car tires.

The race was drama-packed with Moss’ Cooper faltering in the closing laps and Frére snatching an exciting victory. John Hanning won his own battle and, running a consistent race, he coaxed the large front-engine car home in 13th position, 7th best of the local drivers. It was an encouraging start, but Hazel contended, “We needed more power because of the weight of the car compared to the low slung, rear engine jobs.”

The solution came in the form of a wrecked and burned-out 1951 Jaguar Mk. 7. Its 3.4-liter, XK twin-cam with the small valve cylinder head produced about 180 bhp. The A90 was dumped and the Jaguar engine fitted. The car became known as the Austin Jaguar. The company that Neville worked for was a Jaguar agent, so spares could be obtained cheaply.

Hazel remembered, “We ran it at first with 1¾-inch SUs, and with the compression ratio of 7 to 1 it was in a very mild state of tune. With a weight of some 1800 pounds it was a little slower than in Austin form. Then we increased the compression ratio to about 8.5 to 1. The fuel that was available was not very good, and we mixed it with Union Spirit, a local brew made from sugar.”

Neville introduced John to Geoff Pindar, the general service manager at Jaguar in the UK, and Hanning was able to obtain a brand-new cylinder head complete with inlet manifold and linkages that they believed were from a D-Type.

John owned a Jaguar XK150, so it was further decided to fit XK150 hubs and wheels to the new racing car. The story goes that a batch of XK150 hubs had left the factory without the splines being greased and as a result there were customer complaints from around the world because some XK150 hubs had developed rust. As a result, Neville had to order a new set of hubs for a customer’s XK150. The rusted hubs from this car were repaired by the Hannings and fitted to the single-seater.

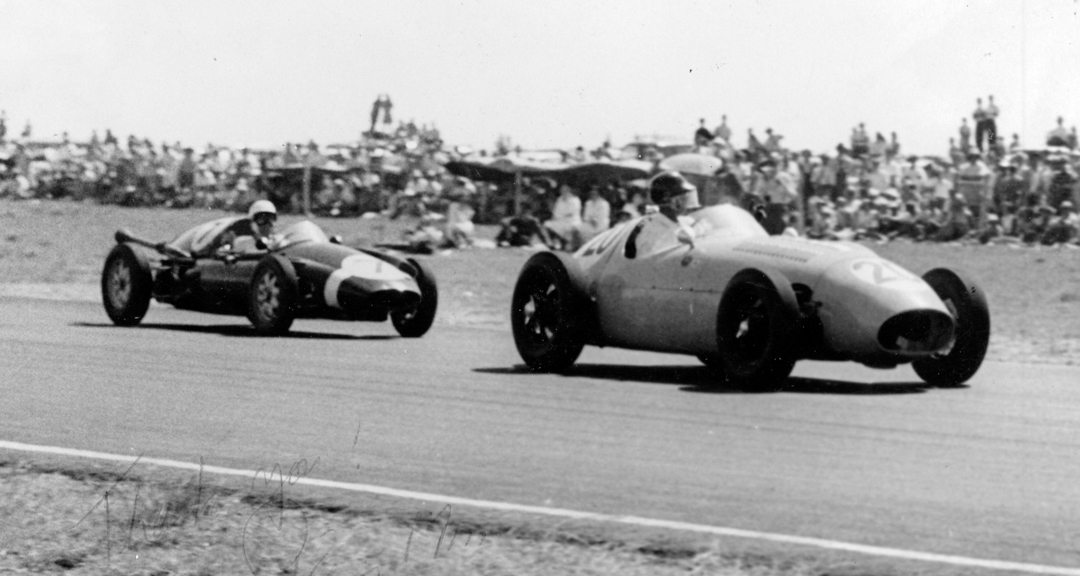

With the D-Type head and triple Webers the 3.4-liter twin-cam was probably producing between 220- and 240-bhp, and in November 1960 the car emerged as winner of the short but keenly contested Racing Car Scratch race at the new Killarney circuit in Cape Town against a field that included some new rear-engine machinery. This was a good warmup for the International Cape Grand Prix three weeks later at the same circuit.

Stirling Moss and Jo Bonnier, in F2 Porsche 718s, overshadowed everyone on their way to a convincing 1-2, with Wolfgang von Trips 3rd in a Lotus 18-Climax. Due to the excessive summer heat, sections of the new track broke up and driving became tricky. In gruelling conditions the immaculate Hanning Special soldiered on to finish 11th overall and 6th best of the local drivers after two hours of racing.

A fortnight later, at East London, Hanning knocked some eight seconds off his qualifying time at the previous South African Grand Prix during practice for the 7th SAGP.

“We had upped the compression to just over 8 to 1 and she certainly stretched her legs down the long straight,” recalled Hazel. The Hanning Special was as quick as the beautifully built rear-engined Jennings-Porsche, and quicker than a Maserati 200SI, Sam Tingle’s Connaught, a mighty Chevy V8-powered Cooper T20, a Porsche Spyder and others.

While Moss and Bonnier dominated in the 7th South African Grand Prix at East London with Jack Brabham (Cooper T53-Climax) finishing 3rd, Hanning had another trouble-free run, although, as usual, he kept a keen eye on the temperature gauge. The radiator was far too small for the job and the engine was prone to overheating. For much of the race, John tussled with the Connaught of the vastly experienced Rhodesian champion Sam Tingle, on his way to a 12th-place finish and 5th local driver home. Looking back, it says much for the stamina of the part-time racing amateur driver to be able to wrestle a bulky front-engine car around for a race enduring over two hours averaging some 80 mph.

Then, suddenly, it was all over.

In 1962, the Royal Automobile Club changed the regulations for championship racing in South Africa, limiting the grids to cars with engine capacities of up to 1.5 liters. With his special effectively banned from the grids and approaching the age of 50, John was forced to retire. Racing in southern Africa, for better or worse, had moved closer to “professionalism.”

The late Frank Hoal commented: “With the Austin Jaguar he showed what he could really do in a car that was more competitive than his previous cars, although still rather large and heavy. It was a great pity that he had to retire when he was really on the way up.”

For the talented design team the story did not end there. In those days with “wide open spaces” between the cities and towns and no speed limits, high-speed touring could be fun.

So, it was decided to use the Jaguar engine and other bits of the racecar to build a very special sports car.

Once again, through their contacts with the BMC plant they were able to acquire an Austin-Healey-looking bodyshell that Ralph Clarke, a works engineer at the factory, had built up when he constructed a special sports racer using an MGA 1500 engine and Austin-Healey 100 chassis. The special used standard Healey mudguards, doors and rear fenders, but Ralph made up his own front section and nosecone.

Ralph quips: “The powers that be did not like it as it was raising speculation what we might market next, and I was told to break it up. We gave the shell to the Hannings and they adapted it to fit their chassis and Jaguar setup. It was quite a handful to drive, but the straight-six made a lovely sound.”

Hazel did practically all the alterations, and the car complied with Appendix J International sports car regulations. Sadly, the beautifully made single-seater bodyshell met an inglorious end when it was dumped to make space in the garage. It was last seen in a chicken run.

Hazel recalled, “We had to widen our single-seater chassis to take the wider track. The Austin-Jag in road racing form was never raced, but we were very proud of it and had a lot of fun with it. It used the XK150 wire wheels, and we shod it with Dunlop CR65 racing tires. I remember once doing 100 miles in 62 minutes on a stretch of public roads.”

The original engine of the Aston Martin Ulster was located, and the car was restored by Ecurie Bertelli to be raced by Judy Hogg in British historic events. The Austin Jaguar was rebuilt in South Africa and still runs about.

John passed away in May 1984, and Hazel and the girls relocated to America where the remarkable lady engineer passed away in 2002. The efforts of the Hannings and Neville Wood showed that with ingenuity and innovation amateurs could share the tracks with greats of the time.

Hazel’s eldest daughter Judy Gregg, who now lives in America remembers, “Those were great days of my life, and we had a lot of fun even though some were a bit hair-raising to say the least. My parents made some good friends, and consequently lots of friendly rivalry in those simpler days of racing. What I learned about cars has been a great help to me all my life, although nowadays cars are so complicated with computers I would not know where to start. I still love driving and would rather drive somewhere than fly if at all possible.”