1971 Tecno F2

The brothers Pederzani—Gianfranco and Luciano—ran a hydraulic pump company in Bologna. In 1962, they started up a second company to manufacture racing karts, known as Tecnokarts. Amazingly, within ten years they constructed and ran an F1 car—some people would later say that they should have stuck to pumps!

While this last sentiment was grossly unfair to the hardworking brothers, it is however, true to say that they went too far too fast. Their karts were immensely successful with many national championships going their way throughout the 1960s. They moved up a step by producing a tiny F4 car with a motorcycle engine, usually a 250 cc Ducati, then a similar but bigger machine for the Italian national F850 championship. In 1966, they turned their attention to F3. The works car won a European F3 round in 1967 and then took the Championship in 1968 and 1969. At the time, Tecnos were also winning French, Italian and Swedish national F3 championships.

The early F3 car was little more than a scaled-up F250 with a Cosworth engine, outboard suspension, a short wheelbase and a very “stubby” appearance. The 1967 space frame was much more refined, with the independent front and rear suspension incorporating double wishbones and coil spring damper units, with long radius arms at the rear. In spite of the squat appearance, the F3 Tecno was aerodynamically efficient and very quick on fast straights. Sales of these cars were healthy throughout 1968 and 1969—helped by Ronnie Peterson and Jean-Pierre Jaussaud winning in spectacular style—so a Formula F2 project was soon undertaken in 1968.

The 1967–’71 1600 cc formula for F2 was seen by many as the “Golden Era” of F2 (which might be disputed by some of those who raced in or were part of the previous series in the early 1960s) but it certainly brought many drivers to the fore who were in or went on into F1. The chunky little F2 Tecnos, like their F3 predecessors, were “chuckable,” and their karting heritage was very evident, with precise, sensitive steering and braking and a back end that could be placed anywhere on the track. The early F2 car was so small that it appeared to be only engine, wheels and suspension, as the driver’s ‘cell’ was compact indeed. In 1968, there were two Tecno teams running in the series, with Regazzoni entering 11 races but only scoring 13 points, with a 3rd place at Crystal Palace his best finish. However, Regazzoni and Jaussaud suffered several big accidents with their cars that year. In 1969, a single works team was run, with François Cevert giving Tecno their first F2 victory at Reims.

In 1969, older brother Luciano Pederzani retired, but Gianfranco kept a frantic pace of work going. As a result, the new F2 car for the 1970 season had substantial modifications. Though its heritage was still evident, the basic tubular chassis was refined and several changes were made to the suspension to make the handling more predictable and stable. The body was much improved and was generally flatter, and a new wide nose was tried. Interestingly, Tecno’s design to use a split radiator with air ducted in through each side of the wide nose is thought to be the first attempt at this approach. After such difficult seasons in ’68 and ’69, it came as something of a shock to the other teams when Regazzoni won the 1970 Championship, using an older car for one win and the new car for the other three. François Cevert rounded out the season by also claiming a win in 1970.

Originally, the Tecno F2 cars had started using primarily Cosworth BDAs, but it was not long before the Pederzanis were taking the basic Ford unit and rebuilding it to their own specs. This continued throughout the life of the formula and the works cars had the Tecno-tuned units, which occasionally suffered reliability problems.

Photo: Peter Collins

At some point late in 1970, or early in 1971, Gianfranco and the team made the decision to go into Formula 1, a fateful and possibly fatal…decision. Whether it was due to Tecno’s newfound focus on F1 or not is anyone’s guess, but Tecno’s 1971 F2 car was little changed from the previous year’s model. The Tecno-BDA needed considerable work in the reliability department by then but it didn’t get it, which was unfortunate because some significant and talented drivers were to be behind the wheel in 1971. Marco Bodini, whose father was a works Tecno driver, and had chassis 716 in his possession for many years after the 1972 F2 program was shelved, says that the 1971 cars were not new chassis. He states that a large batch of cars had been built in 1970, and several of the frames were slightly revised, renumbered and used for 1971. It is not clear whether these particular chassis had been used at all in 1970. The French oil company, ELF, sponsored the works team for 1971, and with the funds available, it is unfortunate that the cars were not developed further. Bodini adds that he believes that it was the F1 plan that really spelled the end for the F2 program.

716 and the 1971 F2 Season

Chassis 00716 had a remarkable, if not entirely successful, racing career while its drivers were some of the most memorable in the business, both in F2 and Grand Prix racing. These included Jean-Pierre Jabouille, Patrick Depailler, Ernesto “Tino” Brambilla and François Cevert, all of whom had solid Formula One careers.

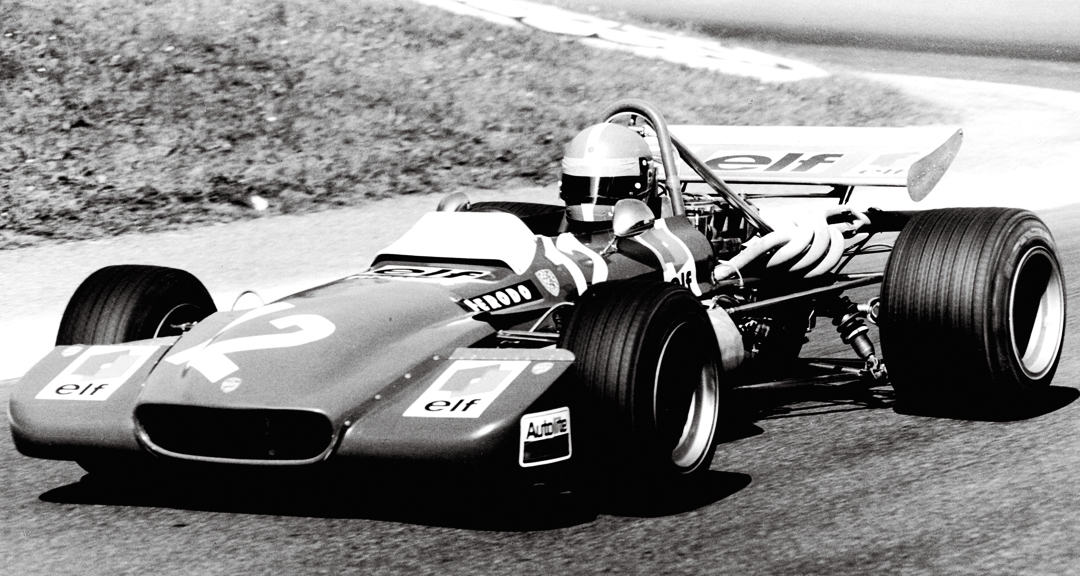

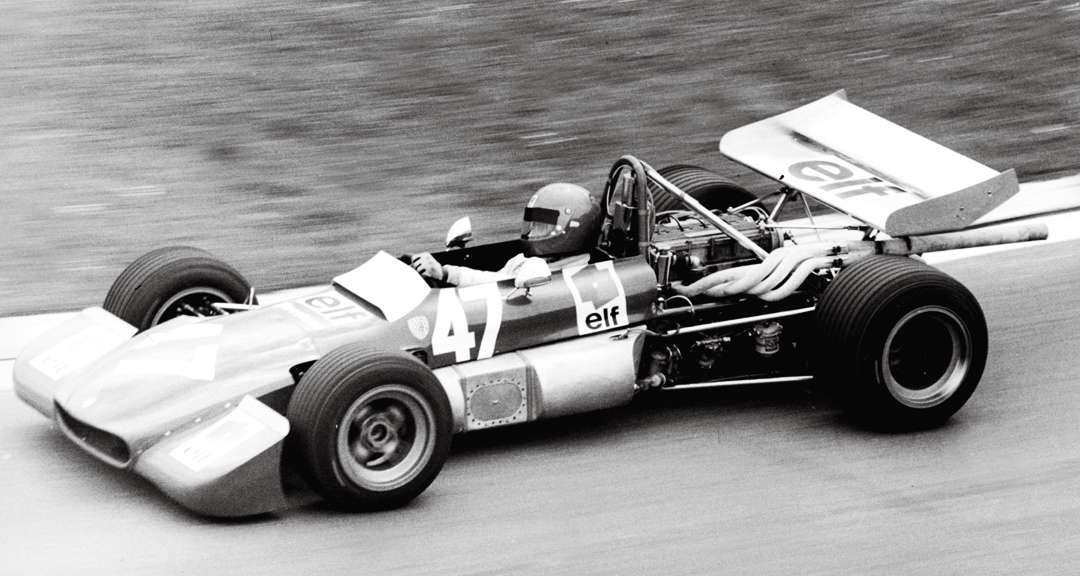

The F2 Tecno, with the newly developed Ford BDA-inspired engine with belt drive, first appeared at Hockenheim, the initial round of the 1971 Championship. It had ELF instead of Motul decals that year, and it was the ELF money that was funding the limited engine development. The race was run in two 20-lap segments with Cevert (712) disposing of the fancied Ronnie Peterson’s March 712M to win the first heat. Depailler (714) retired with a broken injection trumpet, while Jabouille qualified 15th and finished 12th. Cevert’s 3rd in the second heat was good enough to give him the overall victory so it was a fine debut for the team.

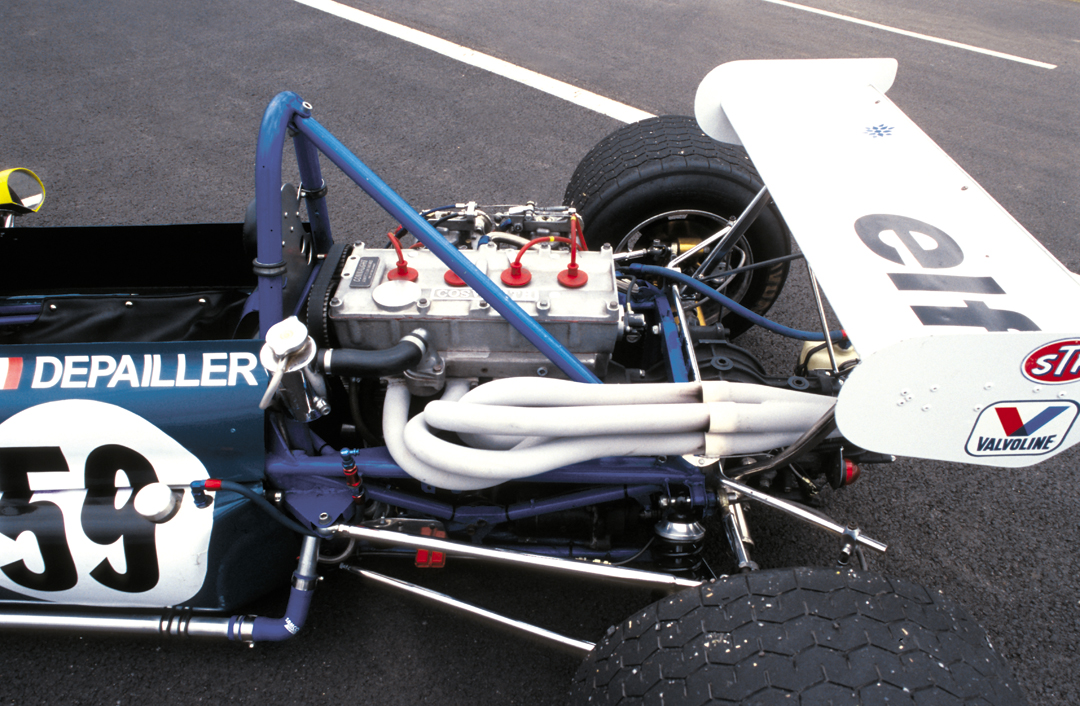

Photo: Peter Collinsreliability and ease of maintenace. The carbureted BDA pushes 210 hp through a five-speed Hewland FT-200 gearbox.

Photo: Peter Collins

At Thruxton a week later, Graham Hill driving a Brabham BT36 won after two 28-lap heats, from which the fastest cars would go into a 50-lap final. Cevert was penalized in 712 for a push start although his car was handling badly on the sweeps of Thruxton. Depailler in 716 had qualified 12th but his engine let go so he was forced into retirement. Cevert managed to drag his wallowing Tecno into 4th after a very hard race. There was a nonchampionship round at Pau in south-western France on April 24, where Jabouille qualified 716 in a strong 6th spot and then drove a superb race to finish 2nd, providing the best result all season for this chassis.

Cevert scored another victory at the Nürburgring in 712, in the Eifelrennen, ahead of Emerson Fittipaldi, Carlos Reutemann, Peter Westbury and Graham Hill, but Depailler, who had qualified 14th in 716, had the oil pressure disappear and he eventually retired. At this point in the season, Cevert was building up a points lead in the Championship, due in no small part because the engine was reliable at that stage. Two weeks later, the cars were all at Jarama in Spain and the Tecnos were out of luck with Cevert crashing 712, and Depailler not racing because his engine could not be readied on time. Depailler then drove 716 at Crystal Palace where he qualified 8th and was going strongly when the engine let go on him for the second race in a row. Tecno fortunes were on the downturn at Rouen as Cevert crashed his new car, 722, with a wheel breakage, followed by another engine breakage at Mantorp Park. The Italian Ernesto “Tino” Brambilla, one of the exuberant brothers Brambilla, was in 716 at Mantorp Park, and—lo and behold!—he managed to crash it in the same spectacular style his brother was noted for!

At Tulln-Langenlebarn, in Austria on September 12, in dangerous wet conditions, Cevert drove 716 in the first heat where he managed to finish 4th. It seems that he and Depailler may have been swapping between 716 and 722, but Depailler managed a 9th in the second heat after qualifying 17th. Cevert suffered wet electrics in part two and was now losing contact with Peterson for the championship. Cevert then retired 714 at Albi, where Depailler had qualified 19th but again had an engine failure and didn’t finish. Cevert was at the final round at Vallelunga in 722, where his radiator exploded, covering him in boiling water. That resulted in Schenken having a big crash trying to avoid him. Thus, Cevert had dropped to 5th in the Championship won by Peterson from Reutemann, Dieter Quester and Tim Schenken. Chassis 716 had a quick rebuild after Brambilla’s crash but Depailler didn’t feel it had been done correctly, and that ended up being its last race in the period.

Another full F2 program, which had been expected for 1972, was dropped as the Tecno F1 project advanced, so several of the F2 cars were moved to the back of the factory, as happened to a number of Tecnos. Chassis 716 was eventually sold or given to works driver Bodini, and seems to have stayed in his collection with other Tecnos for many years. In 1999, several of the cars then came on the market, at which time 716 was sold to the UK but never completed.

Nick Wadham and Andy Kirkby pooled their resources two years ago when the car was being advertised on the Internet, among other places. The ads said it required essentially a checkover, a fire extinguisher and fuel tank, but in fact a number of parts were missing and they undertook a complete rebuild from the chassis up. All the rose joints were worn, and it was decided in the interest of safety that it needed to be done thoroughly, although much of the original car has been retained. Aside from replacing missing and nonworking gauges with newer and more reliable ones, nothing else has been remade. When the car made its debut at Donington a few weeks before this test, it was the first time that 716 had turned a wheel in anger in over 33 years. However, the owners were rewarded with a satisfying 3rd in class in this maiden event.

Driving an F2 Tecno

It’s always an interesting experience to be involved with an historic racing car that is just re-emerging. In spite of Nick Wadham getting a good result a few weeks earlier, there was still some shaking down to be done on 716. There is always a danger of assuming that a 1600 cc F2 car might be rather tame, but that would be a serious mistake. With a weight of just 450 kilograms and 210 bhp on tap, this is a potent combination, and as a result the owners have been cautiously working themselves through familiarizing themselves with the car. Their plans include running six or seven races in the Historic Derek Bell Single-Seater series, and perhaps an international event at Spa in September. If the rebuild of the BDA at the end of the season doesn’t eat up all their funds, they will be aiming for the historic F2 Championship in Europe in 2005, where a well-known car such as this will be very welcome.

Photo: Peter Collins

Chassis 716’s BDA is now running on carburetors instead of the original injection, mainly for reliability and to keep the costs of the enterprise down to a manageable level. Injection adds a lot of time and expensive parts to the quotient and demands constant fiddling. Andy Kirkby reckoned that there is only a loss of about 2 to 5 bhp with the carbs, and that is only coming out of the corners and on the start line whereas everywhere else it is about the same as the injected engines. As part of the restoration, 716’s engine was carefully rebuilt, as was the Hewland FT200 five-speed gearbox, both of which have been in the car for all these years. Wadham and Kirkby had a lot of difficulty getting and keeping the engine running in the first months that they had the car going, but now the maintenance input seems to be limited to in-between race cleaning and checking. There is a tendency for air to collect in the water system, so it needs to be bled regularly and it runs somewhat hot. Oil temperature is slow to rise so caution has to be exercised in the warming up period, especially on cold British days. I found that the engine wanted to be run at no less than 2000 rpm, as it will foul, though it actually seems to sit happily on tick over. The BDA is a refined unit though knowledge of its particular habits is useful.

When I was finally ensconced in the car—or perhaps stuffed into is more apt—I could begin to concentrate on how to keep the tricky short-wheelbase machine on the road. Like many single-seaters built for diminutive racing drivers, this is a tight fit, although also like many similar cars, once you get into the proper low-down position and relax, it doesn’t feel so tight. The snap-on leather racing seat covers a fuel tank right beneath one’s posterior but it’s comfortable. The bigger problem will be getting out, and being embarrassed by requiring three people to help do it! But it’s so nice to be sitting in a car with Patrick Depailler’s name on it.

The tight cockpit means the Tecno three-spoke wheel is in your face, with the gearshift off to the right. The rev counter reads to 12,000 but is red-lined at 9,000, with temperature and pressure gauges and not a lot else. I had a bit of work to get my feet down to the pedals as they need to be raised over a cross member. I certainly got them stuck getting out.

Photo: Nick Loudon

The warm-up period is slightly prolonged, after having been rested by Nick’s first runs on the Silverstone circuit. A few tire pressure and wing adjustments have been made, the tires are warmed up and that buzzing BDA from the four-into-one exhaust on the left sends you off in the smooth Cevert-Depailler-Jabouille (but hopefully not Brambilla!) mode. The kart origins are instantly noticeable, highlighted by very sensitive steering. It doesn’t take long to feel the understeer in quicker corners—I like that—and oversteer when you boot it out of the slower ones. I like that too, but I am pleased it’s dry today. The torque provided by the presence of carburetors rather than injection makes the gearbox use more flexible, and as Nick says, it allows you to get away with a wrong gear occasionally, which I quickly found out. Andy and Nick are rapidly gaining knowledge about choosing ratios in order to extract the most from this engine on carbs.

The small and compact size means the car is very nimble—that characteristic comes across almost instantly. It can be placed on the road where you want it, it avoids slower cars with ease and behaves well when cornering off the “proper” line. I get a lot of practice at that particular activity, and there are some cars that just sense when you are off line and try to throw you into the scenery, but not the Tecno. It is well balanced and set up softer than it was in the days of Depailler and Co. Harder settings will be tried when the handling is better mastered. It is certainly possible to drive deep into a corner, leave the braking late, keep the power on, let the back end out and drive it on the power. Photographer Collins may attest to this as I came extremely close to his toes, looking totally out of control, but such was not the case! You can definitely slide the car without losing it, and that is an interesting dimension of a car with such a short wheelbase. On harder settings, though, I expect that moment gets hairier and these cars did have a fair number of “incidents.”

The car I was driving has just had new brake discs fitted. It started with discs which were grooved, and the braking was anything but predictable. As you can’t buy these discs off the shelf, they had some made and they have made a considerable difference, inspiring greater confidence in taking the car closer to its limit. The pads were bedded in quickly and the solid pedal showed a big difference, allowing Nick to circulate at respectable lap times. The car is slightly slowed by not having slicks at this point, but it is reaching top revs in fifth gear at two points at Silverstone. The improved braking allows for very hard stopping into the tight corner at the back of the circuit where the back end tends to slide out, and slicks would improve the acceleration down the straight. The Hewland gearbox was behaving faultlessly, with just a snick to get it up and down the box. Stiffening the suspension might also make the aerodynamic efficiency of this car more obvious, although it will then put greater strain on the brakes. Like all racing cars, the more you do, the more you have to do! At the moment, however, the car has a superb sense of balance and is intrinsically easy to drive.

Nick Wadham, who raced Renault-Alpines, says he likes the car because it feels like the Alpine, with everything happening at the back. As another Alpine devotee, I have to agree with him—there is that great sense of things happening, and the driver’s challenge is to manage them.

Buying and Running an F2 Car

The car was up for sale at a bit over $30,000, a very fair price for a machine with the history that this car has, with all those rounds of the 1971 F2 Championship behind it in the hands of some superb and colorful drivers. A fair amount of work and cash has now gone into bringing it up to a safe and competitive state so the car’s value is probably closer to $50,000.

Maintenance, as Nick and Andy have said, is pretty routine, as long as you know how to take care of a BDA engine and you are good with your in-between race care. There is nothing inherently complex about the car, but it helps if you have some race engineering experience and you are good at sourcing the parts needed. Tecno spares come at something of a premium!

Oh yes—you do also need at least two friends to haul you out of it when you are finished!

Specifications

Chassis: Tubular space frame

Track: Front: 1380 mm; Rear: 1380 mm.

Wheelbase: 2100 mm.

Weight: 450 kilograms

Engine: Cosworth BDA

Carburetion: Originally fuel injection, currently on twin Weber 48DCO2

Capacity: 1596 cc

Power: 210bhp @9000

Gearbox: Hewland FT200 5-speed

Brakes: Girling discs

Tires: Avon Racing Front: 9.0/20/13; Rear: 12.0/23.0/13

Wheels: Tecno

Resources

Guba, E.

Motor Sport Annual Number 5,

Grenville Press, 1972

Hodges, D.

A-Z of Formula Racing Cars 1945–1990

Bay View Books Devon, England 1990

Grateful thanks to Nick Wadham and Andy Kirkby for their help and loan of their car.