After World War II, Enzo Ferrari began the work of retooling his small company from manufacturing parts for Italy’s war effort, to the manufacture of racing cars. Prior to the war, Ferrari had served as racing director for Alfa Romeo’s racing efforts, and as such, had been involved in the construction and campaigning of many of Alfa’s seminal racing cars, including the remarkable 1937 1.5-liter, supercharged Alfetta 158.

While heading this later project for Alfa, Ferrari was “loaned” the services of one of Alfa Romeo’s very talented designers, an engineer by the name of Gioacchino Colombo. As a result of this early collaboration, in 1947, when Ferrari embarked on the creation of his own eponymous racing car, he enlisted the services of Colombo to pen for him a bespoke engine. Whether due to Colombo’s previous experience with designing a V-12 engine for the prewar Alfa Romeo 12C, or due to Ferrari’s known affection for the V-12 engines found in early Packards and racing Delages, Colombo was directed to design a 1,496-cc V-12 for what would become known as the Ferrari Type 125. Unknown to either Ferrari or Colombo at the time would be the incredible legacy that this diminutive powerplant would forge over the course of the next 30 years.

Making Racing Profitable

Over the course of the next seven years, Ferraris would take the postwar racing world by storm. Cars like the 166 MM and 212 Barchetta brought racing success to Ferrari and with it, increased demand and therefore sales of his high performance sports cars. Up until 1954, Ferraris could be ordered in any manner of specification, from full-blown racer to grand tourer. But in the case of the later, these were really racecars that had certain creature comforts added to them to make them more amenable to being road cars. Along with this was the fact that each example up to that point was to a greater or lesser extent a bespoke car—with a total output of only 189 cars through 1953, the production of Ferraris was still very much a cottage industry.

However, late in 1953, Ferrari undertook a fundamental change in his business approach. Rather than just selling racing cars, or road-adapted racing cars, Ferrari reasoned that the creation of a dedicated line of road-going GT cars, could capitalize on his racing success, with increased sales. The profit from these sales could then be poured back into the development of his racing cars. With this in mind, at the 1953 Paris Salon, Ferrari unveiled what would eventually become its first “production” touring car, the 250 Europa. Put into production in 1954, the Europa featured an enclosed coupé body by Pinin Farina on a ladder frame, with a coil spring independent front suspension and live axle at the rear. For power, in the production Europa GT, Ferrari chose to utilize the 2953-cc version of Colombo’s Type 128 V-12 engine. With a 73-mm by 58.8-mm bore and stroke the 3-liter Colombo V-12 yielded a single cylinder displacement of 250-cc, thus giving rise to the 250 GT (Grand Touring) moniker that would carry on in the lineage of Ferrari GT cars to come.

From Europa to Boano

The popularity of the Europa led to an updated version of the 250 GT for 1956. In 1955, Pinin Farina began work on an updated 250 GT body that featured a lower roofline and improved passenger comfort and luggage space. The original intent was for Pinin Farina to not only design the bodies, but to also build them. However, production capacity at its Corso Trapani facility in Turin was exhausted and plans for building a new facility on the outskirts of Turin had been delayed. As a result the new design was farmed out to Carozzeria Boano for construction.

The new 250 GT prototype made its debut in coupé and cabriolet form at the March 1956 Geneva auto show, while the Boano-built coupé made its first appearance at the Paris Salon in October 1956. The new Boano was mechanically much the same as the Europa GT, with the Type 128, 3-liter Colombo V-12, driving through a 4-speed gearbox. The Boano GT was built from 1956 to the spring of 1957, when Mario Boano left the company to go to work at Fiat. As a result, the carozzeria was given to his son-in-law Ezio Ellena and renamed Carrozzeria Ellena, which is why 250 GT examples built from 1957 to 1958 are commonly referred to as a 250 GT Ellena. So well received was the Boano/Ellena that in 1958 Car & Driver crooned, “The 250 GT is a masterpiece. Hardly any other cars in the world compare with it—except other Ferraris.”

Of Cabs and Spiders

In 1957, Ferrari and Pinin Farina turned their serious attention to the creation of a series of convertible Ferrari GT cars. It is at this point, that a clarification of Ferrari nomenclature is in order. After its creation, Ferrari established essentially two familial lines of 250 GT. One branch of this family tree were termed Berlinettas, these were enclosed GTs like the long wheelbase “Tour de France and the short wheelbase “SWB” designed for racing, with a minimum of creature comforts or sound deadening. The other branch of the family tree were the 250 GT coupés, such as the Europa, Boano and Ellena, which featured more comfort and luxury and were not necessarily intended for racing. This distinction between the two branches becomes important in 1957 and 1958 when Ferrari and Pinin Farina embarked on a new generation of convertibles built on the 250 GT platform.

At the 1957 Geneva auto show, Pinin Farina unveiled a new 250 GT cabriolet. Decidedly low, sleek and sexy the new convertible featured a highly unusual asymmetry in that the driver’s side door was “cut down” as was then common with many British sports cars of the day, but not the passenger door! The chassis and drivetrain were of the same type used in the Boanos and Ellenas, though this prototype was later fitted with something new and experimental for Ferrari, Dunlop disc brakes. Used as personal transportation by Ferrari team driver Peter Collins, this particular 250 GT Cabriolet would serve as the first of a limited number (40 examples) of what would come to be known as the “Series I” cabriolets (though the balance of these Series I cars would carry on Ferrari’s traditional use of drum brakes).

Interestingly, the following year Ferrari was encouraged by California importer John Von Neumann to build a variant of the Cabriolet that might be more suited to racing. This convertible would be very similar to the Series I Cabriolet, but would be constructed using the long wheelbase, Berlinetta line of 250 GT as its basis. While visually very similar to the Series I Cabriolet, this new 250 GT Spyder California was a different beast that featured a detuned version of Ferrari’s potent 3-liter “Testa Rossa” race engine, with a subtly modified body, designed by Pinin Farina, but built by Scaglietti.

The Series II Cabriolet

One of the unintended consequences of creating the California Spyder was how very similar it looked like the Cabriolet. With Ferrari wanting to maintain a more clearly separated lineage between racing (berlinettas and spyders) and touring (coupés and cabriolets), it was deemed necessary to create more of a visual distinction between the two convertible variants of the 250 GT.

With this in mind, at the 1959 Paris Salon, Pinin Farina unveiled a new “Series II” Cabriolet, alongside an updated 250 GT Pininfarina Coupé. The new cabriolet looked much more like the coupé than it did the California Spyder, with a less aggressive nose and less flowing lines. While the new lines of the Series II Cabriolet were viewed by the contemporary press as being a bit staid compared to the Series I and California Spyder, improvements and refinements to the mechanicals made the Series II Cabriolet and Coupé extremely popular with the motoring press. Road & Track enthused, “We found the coupé to be not only confortable, responsive without being temperamental, and agile, but also one of the easiest cars to handle we’ve ever driven. This is a car designed by enthusiasts for enthusiasts.”

One of the many mechanical improvements on the Series II that so impressed the popular press was the inclusion of 4-wheel disc brakes—the Series II being the first production Ferrari to be so equipped. Other improvements included the replacement of the old Houdaille lever arm shocks with telescopic shock absorbers and the addition of an electrically-operated overdrive unit. Even the venerable Colombo V-12 received a series of upgrades including revised cylinder heads. Essentially a redesigned version of the heads found on the successful Testa Rossa racecar, these new units relocated the spark plugs out of the vee to the outside of the engine, which not only improved ease of maintenance, but when combined with other modifications cured the earlier head’s tendency to blow head gaskets. The redesigned cylinder heads also saw a return to the use of twin distributors, running off of each cam bank, which reduced the earlier engine’s tendency to devour distributor caps! Further, the three downdraft Weber carburetors were increased in size to 38DCL’s and these now fed charge through 6 individual intake ports, rather than the earlier engine’s siamesed arrangement.

With all these developments the Series II became the most refined Ferrari touring car to date. Fast, luxurious, it became the ideal of what the well-heeled gentleman should drive. In fact, many contemporary reports went so far as to stress the fact that they felt the Series II was so easy to drive…that it would be suitable for a lady! While these later statements would likely have made racer/journalist Denise McCluggage grit her teeth, in 1960 Sports Car Graphic did honor the 250 GT with its “Sports Car of the Year” award.

In all, 202 examples of the $12,500 Series II Cabriolet were produced from 1960 to the end of 1962. While the California Spyder would continue to be offered into 1963, it wouldn’t be until 1964’s unveiling of the 275 GTS that a new Ferrari convertible would be introduced.

Sampling a Sweet Cab

The example you on these pages is an “early” Series II Cabriolet, that is to say it was approximately the 72nd one of the first 100 examples built. These early cars are different from the late ones in several subtle ways. The later cars feature a center dash section, which connects the transmission tunnel with the dashboard. Additionally, many of the early cars, like this one, still retained the Houdaille lever-arm shock absorbers, the transition to telescopic shocks not occurring until closer to the final 100 Cabs built.

Glistening in the mid-day sun, this Cabriolet (Chassis #2077GT) looks like it could easily take center stage in a ’60s Fellini film. While ideal for playing the part of the daily driver of an Italian industrialist, in reality this example was sold new directly from the factory to Northern California, and has only enjoyed three owners in its lifetime. In more recent years, Chassis #2077GT received an exacting restoration by Antique Auto Restoration, of Carmel, California, in 2007.

While perhaps not as overtly “sexy” as its curvaceous sibling the California Spyder, the Cabriolet is by no means the dowdy spinster of the family. The Cabriolet was intended to have more “sophisticated” lines such that it would be the car of choice, for say a wealthy businessman, as opposed to a flashy starlet. In this regard, the Cabriolet’s styling hits the mark with what can only be described as “sporting elegance.”

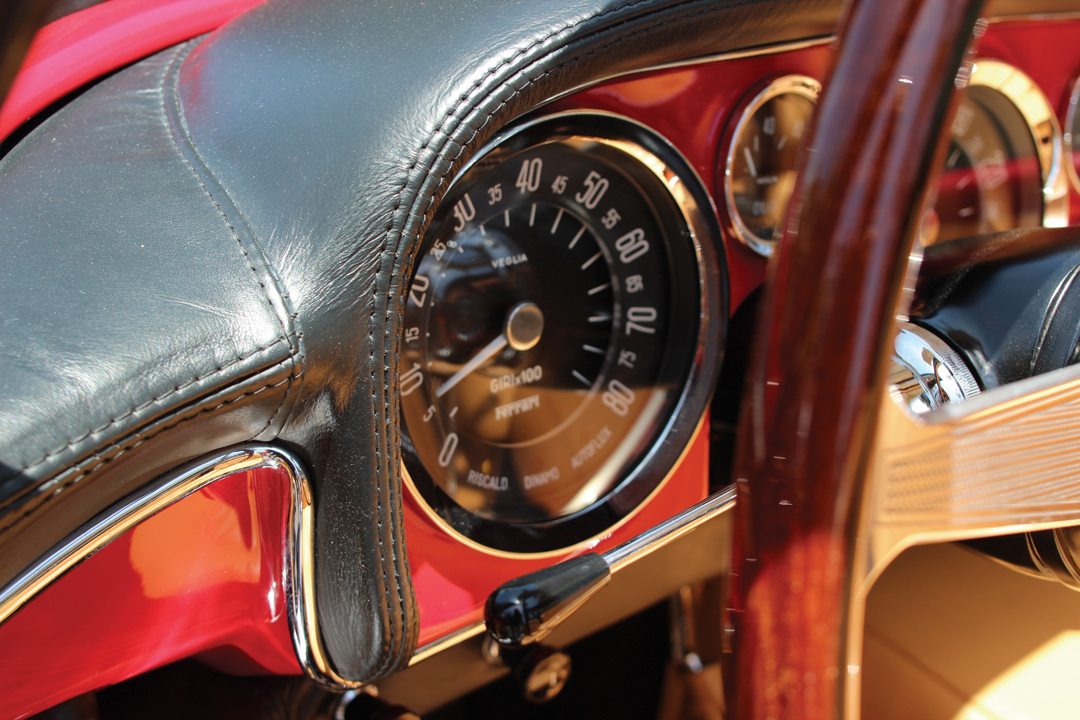

Open the driver’s side door and it’s necessary to dip one’s right leg under the large wood-rimmed Nardi steering wheel, in order to nestle into the large leather seats. Since the Cabriolet was designed for touring, and not racing, the large, upright seats are more akin to a split bench seat, than a racing inspired bucket. While eminently comfortable, one tends to sit on these, rather than in them, as you would in one of Ferrari’s more racing inspired 250s. Seating position is of the early Italian school—upright, with the floor-mounted pedals very close for a tall driver.

Reaching to the very center of the dashboard, I give the key a full turn and then push it into the dash. After a brief whirl of the starter motor, the 3-liter, V-12 burbles to life and instantly lays down into a quiet idle.

After, dipping the clutch and pushing the small black gearshift knob forward, into first gear, a small amount of throttle is applied, and as the clutch pedal reaches about three-quarters of its travel, the Cabriolet gently pulls out onto the road. No bucking, no jerking, just a buttery-smooth, flowing application of power.

At low speeds the Cabriolet feels large, but that is not to say heavy or ponderous. The Cabriolet—at 102-inches of wheelbase and 3,000-lbs—is not a small a car. It is a Grand Tourer, with Grand being the operative term. The Colombo-designed V-12 is not particularly torquey (195-lb/ft), which means that the Cab likes to make its 240-hp higher up the rev range. Begin spinning that all-aluminum alloy mill up past 3,500-rpm however, and the Cabriolet really starts to come alive. The V-12’s deep basso profundo, eminating from the four tail pipes, takes on a shriller note as the revs climb closer to the Cab’s 7,000-rpm redline. As the engine comes alive with increasing speed, so too does the chassis. As speed increases, the Cabriolet becomes progressively lighter and lighter on its feet, revealing the true intention of its creators. While it is perfectly docile in the city, this is a car designed for long, high-speed trips. Out on the open road, the Cab is most at home in that 80-mph to 110-mph range, blasting along open roads, with a sense of confidence and ease that allows the driver to sit back and comfortably enjoy the journey.

Within the current classic car scene, the Series II Cabriolet is an ideal choice for those looking for a Ferrari Grand Tourer to take part in multi-day rallies like the Colorado Grand, California Mille or Tour Auto. Encompassing many of the great elements of the California Spyder, at a fraction of the price ($700,000–$800,00 vs. $3 million-plus), the added level of comfort and luxury will not go unappreciated over the course of 1000-miles of “spirited” driving.

The example seen on these pages (Chassis #2077GT) has received a Heritage Certificate from the Ferrari factory (#0001061) and will be offered for sale at Russo and Steele’s Monterey Waterfront auction, August 16–18.

SPECIFICATIONS

Frame: Ladder-type, welded tubular steel

Wheelbase: 102.3”

Track (front): 53.3”

Track (rear): 53.1”

Suspension: (Front) independent with unequal A-arms, coil springs and Houdaille (early) or telescopic (late) shocks. (Rear) Live axle with semi-eliptic springs located by parallel trailing arms and Houdaille (early) or telescopic (late) shocks.

Engine: Colombo Type 128F 60-degree V-12

Displacement: 2,953-cc

Bore/Stroke: 73-mm x 58.8-mm

Compression: 8.57:1

Valvetrain: Single overhead camshaft on each bank with roller followers and rocker arm activation.

Ignition: Twin distributor

Carburetion: Triple Weber 38DCL twin choke, downdraft

Power: 260-hp @ 7000-rpm

Clutch : Single dry plate

Transmission: 4-speed, all-synchromesh with electrically activated overdrive

Brakes: 4-wheel disc.

Wheels: 6.00-16 knock-off, Borrani wire