While the Northern Hemisphere battens down against winter, we here in Australia and New Zealand are reaching for our suntan cream and heading for the beach, while our motorsport continues right the year round.

Major events such as the Australian and New Zealand Grands Prix have historically been held during the southern summer and before WW2 attracted the occasional overseas driver to compete on our shores in borrowed cars. However, such participation did tend to be a little spasmodic due to the vast distances between Australia, New Zealand and the rest of the world. The introduction of economical international air travel soon put paid to this tyranny of distance and opened up a new motor racing circus in far warmer climates.

In the late 1950s, the obvious pleasantry of this became apparent to race organizers and overseas drivers. With the Northern Hemisphere motor racing season closed down for the winter, drivers and their cars started to make the long trek south to compete in a loosely organized series of races in New Zealand and Australia.

Formula Libre

Motor racing in Australia is controlled by the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS), while Motor Sport New Zealand undertakes the similar role in that country. To attract overseas competitors, they created Formula Libre, which is really another name for Formula “Anything Goes.”

It was not unusual to see on one starting grid ex-Formula 1 Grand Prix cars, ranging from 3-liter front-engine vehicles from the fifties like the Aston Martin DBR4/1, Ferraris and Maserati 250F to any amount of Climax-engined Coopers. There was also the occasional car imported especially for the races, such as Lance Reventlow’s front-engined 2.5-liter Scarab in 1962.

It would be fair to describe it all as week-long festivities interspersed with some serious racing on the weekend. However, the races certainly drew the spectators with crowds of over 20,000 being drawn away from their normal diet of cricket or the beach.

New Formula

To capitalize on the success of the races, the sport’s governing bodies in both countries sought to formalize the races. In October 1963, details of the new championship formula was sent to the Commission Sportive Internationale of the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile. This new formula would be run in Australia and New Zealand during the Northern off-season and incorporate both the Australian and New Zealand Grands Prix. Known as the Tasman Cup, after the body of ocean separating the two countries, the winning driver would receive a cup made up from Australian gold and silver on a base of New Zealand timbers.

Maximum engine capacity was to be 2.5-liters running on pump fuel. With such short notice, some people thought that the universe as they knew it was coming to an end, arguing that with smaller displacement engines the racing wouldn’t compare with the Formula Libre cars. “Make it 3-liters to match the forthcoming 1966 Formula 1 capacity,” many cried in the popular motor press of the time.

However, the organizers knew what they were about. The 2.5-liter formula certainly suited the venerable Coventry Climax FPF four-cylinder engine and in a lot of ways shifted the emphasis on to driver skill, chassis design and importantly, tires.

It was also one heck of a distance to the Cooper and Coventry Climax factories in England. Australians and New Zealanders had been servicing racing engines for many years, but to maintain modern Formula 1 engines was seen as being technically difficult. The Climax FPF was a known quantity, and local organizations like Repco in Australia (for Brabham) and Wally Willmott in New Zealand (for McLaren) could easily provide the necessary servicing. In fact, Repco became so proficient with the Climax engine that the company was manufacturing almost complete engines. In fact, this raised their expertise so much it allowed the Australian company to jump the gun on the rest of the world with their Oldsmobile based Repco V8 with the introduction of 3-liter Formula 1 in 1966.

Interestingly, Willmott and Repco went different ways. The McLaren powerplants started with 2.7-liter engines which utilized a shorter stroke, making them 2.5-liters. This development gave them a slight power advantage over the purposefully built Repco unit. Thus, the McLaren engines could rev safely to 7,300 rpm, a whole 500 rpm higher than the Australian-built engine. The higher revs allowed McLaren to use a slightly lower final drive gear ratio giving greater acceleration.

As it happened, the new 2.5-liter cars proved faster than the previous 2.7-liter ones due to a combination of many factors, such as tires, but also the cars themselves. Both Brabham and McLaren had built cars specifically to suit the Tasman conditions.

Photo: Euan Sarginson

McLaren had previously wanted Cooper to build cars specifically for the Tasman Cup, but Charles Cooper rejected this idea. So McLaren set about to build new cars based on the Cooper design using a semi-monocoque chassis, strengthened stressed steel panels mid-section and top-rear, radius rod rear suspension instead of the usual Cooper practice of using a top wishbone. The result was an extremely narrow car at just 2 ft 1 in wide at the cockpit and with fuel carried in an eight imperial gallon alloy seat tank and a further seven imperial gallons in two tanks on either side of the driver’s legs. All up, weight was just 955 lbs with the 2.5 Climax engine and Cooper-Knight five-speed transaxle. In the end, organizers did eventually relent somewhat on the rules, allowing the use of Avgas.

Long Haul

The Tasman Cup was a series of eight races, with four in New Zealand held over consecutive weekends in January and the second four held during February in Australia. Races were to be restricted to a series of heats alone or heats and a final race of around 100 miles. Events were to be held at Levin, Pukekohe, Wigram and Teretonga in New Zealand and at Sandown, Warwick Farm, Lakeside and Longford in Australia. The Pukekohe and Sandown events were set down as each country’s Grand Prix.

The New Zealand rounds were, for the most part, sensibly staged with two on the North Island and two on the South. However, roads in both countries were nothing in comparison with those in the US and usually consisted of two-lane bitumen following every contour. The thought of towing a Tasman car over hill and down dale behind contemporary Australian-built Holdens or English-built Ford Zephyrs certainly didn’t appeal.

In Australia, the organizers excelled themselves in making life difficult. Sandown is located in Melbourne, the location of the present Australian GP. Warwick Farm is in Sydney, some 560 miles north by two-lane road with very few passing lanes, and Lakeside is a further 600 miles north close to Brisbane, the state capital of Queensland. All in all, a reasonable straight line, but then the final race at Longford was near the City of Launceston on the island state of Tasmania. This meant that the teams had to retrace their steps back south to Melbourne and then catch an overnight ferry across Bass Strait to be in time for practice. Bruce McLaren summed it all up when he called it, “… a ridiculous schedule.”

Teams and Drivers

Photo: Paul Cross

With the status of the Tasman Cup raised into the international arena, both host countries entered two car teams. The Australian team consisted of two Repco-Brabham-Climax cars with Jack Brabham and New Zealander Denny Hulme driving. The New Zealand team, under Bruce McLaren Motor Racing Ltd, ran two Cooper-Climax cars with Bruce McLaren and American Timmy Mayer behind the wheel.

Timothy Andrew Mayer was born into a well-to-do Pennsylvanian family and had graduated with a BA from Yale by the time he was 21. Timmy Mayer’s career was very much guided by his brother Teddy, and he started out in a 2.6-liter Austin-Healey and managed in his first year a fourth in the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) national rankings.

Drafted into the Army in 1961, Mayer continued to race his Formula Junior Cooper as Corporal Mayer when he could. The following year saw him in a newer Cooper winning the Kimberley Cup for the most improved American driver. This led to an unsuccessful drive in a works Cooper in the 1962 USGP, as he was forced to retire with a broken gear lever. Europe called in 1963 and with a new Cooper FJ, he continued to gain experience, especially against the highly successful Lotus FJs. However, his smooth driving style brought him under the gaze of Bruce McLaren and selection as number two driver for the forthcoming 1964 Tasman Cup and Formula 1 season.

New Zealand Rounds

The opening round of the Tasman Cup was held at Levin, a tight 1.1-mile circuit situated close to the New Zealand capital Wellington, and the new McLaren Cooper-Climaxes and Repco-Brabham-Climaxes were the main interest of the near capacity crowd. Despite all the preparation, Jack Brabham stayed at home and left Denny Hulme carrying the flag.

After the first heat, Hulme was on pole with Mayer, McLaren and Australian John Youl in a Cooper-Climax just outside his time. The start saw Hulme and Mayer drag to the first left-hand corner with the American leading by a short nose. For the first few laps, there was hardly daylight separating them with McLaren back in front of the rest of the pack. A third into the race, Mayer overdid it just slightly on a tight hairpin corner and Hulme took the lead. For the remainder of the race, it was Hulme out in front, followed by Mayer and then McLaren. Fourth place was Youl and then New Zealander Tony Shelley in his Lotus-Climax.

Photo: Paul Cross

In a less-than-straightforward point scoring system, drivers could count their best of three races in each country, with the New Zealand and Australian Grands Prix races compulsory inclusions. The points were: First 9, second 6, third 4, fourth 3, fifth 2 and sixth 1.

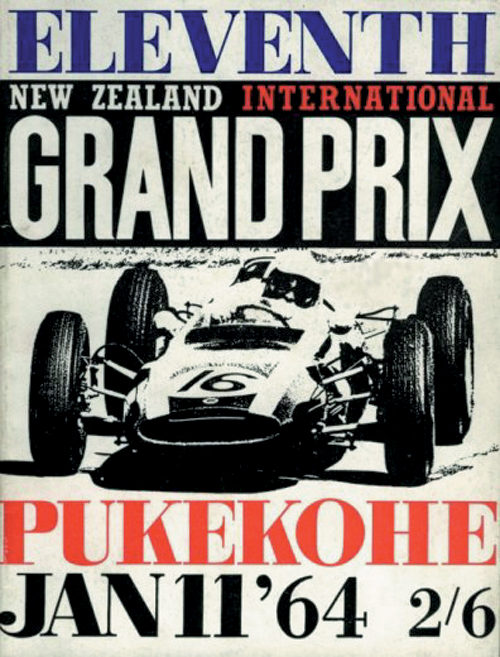

New Zealand Grand Prix

For the NZGP, both of the main teams were at full strength. Pukekohe is located just south of Auckland, and despite the presence of Jack Brabham, it was the start of better things for Bruce McLaren. Following the preliminary heats, it was McLaren on pole sharing the front line with Brabham in a two, three, two grid. Next was Australian Frank Matich in a Repco-Brabham-Climax along with Mayer and Youl.

With the race being 110 miles, McLaren mechanics topped up the tanks of the two cars after the warm-up lap to ensure that the cars lasted the distance. With the lowering of the New Zealand flag, Mayer made an electric start and led into the first corner, only to be soon passed by Brabham. After a poor start, McLaren passed quite a few of his rivals in the first lap to be scored third by the second time around.

Soon Brabham and McLaren had drawn away from Mayer, Matich and the fast-charging Hulme. It wasn’t long before McLaren found the gap he was looking for and took the lead. Matich’s drive was to be short-lived as he soon over revved his engine and ventilated the cylinder block with a broken connecting rod. However, Hulme soon got past Mayer into third. Brabham again passed McLaren and soon caught the back markers, and while passing Shelley, wheels touched, and Brabham’s car shot into the air. McLaren was now in the lead followed by Hulme and Mayer with the positions remaining so until the chequered flag.

Lady Wigram

The teams crossed to the South Island and the 2.2-mile Wigram circuit near Christchurch. With Hulme retaining a short lead in the points, the practice sessions were intense. The circuit was not to everyone’s liking, especially McLaren and Brabham, who were not thrilled with their cars becoming airborne at the infamous Loop. A feeling not shared by the 20,000 plus spectators.

Photo: Paul Cross

After two heats, Brabham was again on pole, with McLaren, Hulme and Youl sharing the line. Mayer was further back following a practice accident damaging the car’s suspension. Youl was first away but was soon passed by both Brabham and McLaren. A few laps into the event, McLaren’s throttle stuck going through the Loop, and after a short excursion into the rough, found himself back at eighth place. Mayer also had further suspension problems, and a long pit stop put him out of contention.

By the 23rd lap, McLaren had made his way up to third, took Hulme and had Brabham in his sights. The leaders circulated like clockwork, with McLaren constantly probing for a place to pass. It wasn’t until the 29th lap when he managed to get past the wily Australian and went on to win. Brabham came in second, followed by Hulme, Youl and New Zealander Jim Palmer in his Cooper-Climax.

Down South

Teretonga is a tight 1.5-mile circuit close by Invercargill, New Zealand’s most southern city. Again, Jack Brabham elected not to compete due to commitments elsewhere, leaving his team’s efforts to Denny Hulme.

Using new wide-section tires, Hulme found himself second on the grid behind McLaren. Mayer was third, with Chris Amon outside him in his ill-handling Lola-Climax. Hulme got away first and soon set fastest lap at 1 min. 5.7 secs. At nine laps, he was the same number of seconds in front of McLaren, and then halfway through the next, he spun hard into the infield and was out of the race. A somewhat surprised Bruce McLaren found himself in front, closely followed by teammate Mayer. Back in the pack, Amon had driven magnificently to gain third but spun off and finished his race rather ignominiously in a ditch.

Then suddenly during lap 35, Mayer shot to the front, and the huge crowd was thrilled at what had now developed into a real race with the lead being challenged and swapped a number of times. With just three laps to go, McLaren again found the lead, and they crossed the finishing line just one-tenth of a second apart. Some ten seconds back was Palmer and Shelly in his Lotus-Climax.

So ended the New Zealand leg of the Tasman Cup with Bruce McLaren firmly leading in the points.

Across the Tasman

Photo: Paul Cross

The first event of the Australian section of the Tasman Cup was the 29th Australian Grand Prix at the 1.9-mile Sandown Park circuit in the City of Melbourne. With practice, the event was spread over four days and all cars had arrived except for the ex-Chris Amon Lola-Climax, which was to be driven by New Zealander Tony Shelley, as it was still in the hold of a cargo ship.

Wet weather during practice certainly put the cat amongst the pigeons, but both McLaren and Mayer were circulating very quickly indeed. Despite their quick times, Brabham nonchalantly arrived at the circuit and set fastest practice time and won 100 bottles of champagne for his efforts. Like the New Zealand events, the races were also open to under-1500 cc cars as well, with local drivers Leo Geoghehan in a Lotus 27-Ford and Frank Gardner’s Brabham-Ford setting the fastest times.

Sharing the front row of the grid with Brabham were McLaren and Matich. As they went past the grandstand for the first time, it was McLaren followed by Matich and Brabham. However, Matich’s fame wasn’t to last, as he dropped out on lap three with gearbox problems. Just five laps later, the leaders were passing the tail-enders, and soon the order was McLaren, Brabham, Mayer, Australian Bib Stillwell, in his Repco-Brabham-Climax, then Hulme and Youl.

Then halfway through the 63-lap race, Brabham passed McLaren under braking and was not seriously challenged again – winning the Australian GP. Bruce McLaren’s race was only to last a few more laps, when a conrod let go and punched a rather large window in the side of the block. Second was Stillwell, then Youl and Mayer.

The Farm

This time the teams headed north along the Hume Highway to Sydney and the famed Warwick Farm circuit. An interesting circuit shared with a horse track that even had two wooden sections where it crossed over the four-legged domain.

Practice was in earnest, especially with McLaren and Mayer who wanted to repeat their New Zealand success. The big-draw card to the event was that Graham Hill, the 1962 World Champion, was competing after being coaxed to Australia by David McKay’s Scuderia Veloce racing team.

However, it was a shock when local driver Frank Matich used his local knowledge to score pole position and the champagne. Alongside him were Hulme and Brabham and behind were McLaren and Hill, also in Repco-Brabham-Climax cars. Brabham’s experience got him first into the corner, but just three laps later, Matich out-braked the twice World Champion to get past him at the end of the straight. Sadly, during the next time into the same corner, Matich speared off into the grass – it was later found out that his chassis had cracked.

With Matich out, the race degenerated into a procession, with Brabham followed by McLaren, Mayer, Hill and Hulme finishing in that order. While it may have been an uninteresting finish, it was good enough for McLaren to give him sufficient points that no matter who won the final two rounds, the Tasman Cup was his.

Lakeside

The next race in the inaugural Tasman Series was 800 miles north to the state of Queensland and the Lakeside circuit. Again, Australian Frank Matich looked to be the man to beat, if only his car would hold together. The circuit also suited Timmy Mayer, who found himself on the front row. Jack Brabham was in very unfamiliar territory sharing second row with John Youl.

The grid positions continued into the race, with both Matich and Mayer commanding a significant lead over Brabham. Then Matich’s bad luck caught him again as a stone found its way through the Weber trumpets, and yet another engine ventilated its block. Mayer took advantage and increased his lead over Brabham, only to find that on lap 16 his engine self-destructed and the car coasted to a stop.

Brabham gained the lead with Youl, McLaren and Hulme close behind. Youl was soon passed, but just a few laps later, McLaren and Hulme crashed wheels, with Hulme retiring. So Brabham made it three in a row with Youl, McLaren and Gardner following up.

Tragedy in Tasmania

Everyone then made the long trek south and across Bass Strait to the island State of Tasmania. Renowned for their hospitality, the City of Launceston and the small township of Longford certainly turned on the festivities for the visitors. The Longford circuit itself was one of the true “round the houses” venues and wound its way around corner pubs, up the main street and across wooden bridges. Graham Hill described it as, “One of the few remaining road racing circuits in the world.”

The weather was warm with just a little breeze, and Timmy Mayer was one of the first out in practice in his T62 Cooper-Climax. What happened next will always remain a mystery. Union Street in Longford had a dangerous hump and while most drivers wished to get over it without braking, most never did. Some think Timmy Mayer became airborne over the hump and landed with the brakes on at something close to 120 mph.

Local eyewitness reports stated that the Cooper landed at an angle and then shot into a tree, splitting it into two. Mayer was hurled 150 ft. landing on his back on the far side of the track with the car disintegrating and its fuel tank found some 450 ft. away. Not aware that Mayer’s 23-year-old wife Garrill and his brother Teddy were at the track, the voice of the announcer came over saying, “Car number 11, Tim Mayer’s car, has crashed – it’s a terrific crash….”

Timmy Mayer suffered a broken neck and was pronounced dead on arrival at Launceston General Hospital. When news got back to the circuit, the US flag was flown at half-mast with the announcement of Mayer’s death made over the public address system. Tim’s team gathered around the Mayer family, and Bruce McLaren announced that he would not take part in any further practice. Team secretary Eoin Young told the local newspaper: “It is the way of death that Tim would have chosen. He was enjoying himself with his foot hard down and lapping a new course at near-record speed – that was all he would have known about.”

Tasmania is a beautiful place, but it is about as far as you could get from the US and still be in the civilized world. In a few short hours, arrangements were being made to fly Mayer’s body back home, but this was very much a rural area, so it was easier said than done. However, the Mayer family had powerful friends, including the Kennedy clan. Tim’s uncle was the Governor of Pennsylvania, and it wasn’t long before the US Embassy was involved and local bureaucracy was swept aside. The body of Timmy Mayer, his young widow, along with brother Teddy and mechanic Tyler Alexander flew out in the dead of night.

With the death of Timmy Mayer, motorsport lost a charming and quiet young American who was heading for bigger things as number two to Bruce McLaren.

The Race

Two 10-lap heats decided grid positions for Monday’s race, with the day itself being overcast and bleak. Brabham was on pole alongside Hill and Matich. Behind came Stillwell and Australian Lex Davidson in a Cooper-Climax. Bruce McLaren started from the back row. The first corner saw Brabham in the lead, closely followed by Hill and Stillwell. Matich soon took over third, and just two laps later, McLaren had caught and passed Stillwell.

On the ninth lap, McLaren moved into third place, and halfway through, Brabham was leading with Hill just four seconds behind. Just three laps from the end, the differential in Brabham’s car cried enough, and he was sidelined. Hill moved into first with McLaren close behind and then Matich, which is how it finished.

Tasman Future

So ended the first Tasman Cup, well and truly won by New Zealander Bruce McLaren. The 2.5-liter formula, as well as our climate, continued to lure works entries from the likes of BRM and Ferrari along with overseas drivers including Surtees, Rindt, Stewart, Courage, Bell and Pedro Rodriguez, which in turn kept the spectators coming. The formula continued until 1969, and Formula 5000 was introduced the following year. However, the big V8s, while fast and noisy, were just not the draw card as expected and Down Under open-wheeler racing proceeded into the doldrums until the inclusion of the Australian GP into the Formula 1 World Championship in 1985.