Vanwall VW14

Vanwall is best remembered for becoming the first British racing car manufacturer to win a World Championship Grand Prix. The first wins came back in 1957 when Tony Brooks and Stirling Moss shared the winning car at the British Grand Prix at Aintree. Moss won again at Pescara a few weeks later and again at Monza. In 1958, with Stuart Lewis Evans also in the team, they clinched the manufacturer’s title in its first season. If the cars hadn’t been so competitive with all three drivers doing so well, one of them, presumably Stirling Moss, would have won the driver’s crown, which, of course, Mike Hawthorn took by one point.

The Background

1958 became the year when Coopers also started to win, and the British cars seemed to have ended the dominance of the Italians (Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Maserati and Lancia) and the German Mercedes. They would have carried on the trend they started except the teams managed to put their heads in the sand when new Formula One rules were announced in late 1958, slated to come into effect in 1961, which dictated a change from 2.5-liter engines to 1.5-liter. The Brits didn’t want it to happen, and they managed to convince themselves that it wouldn’t happen. In essence, that’s how Ferrari came back and stole everything in 1961, until BRM, Lotus and Climax all got their acts together in 1962. However, it wasn’t until 1969 that another country’s racecar builder got a look-in when Matra took the manufacturer’s championship, (though that was a Matra-Cosworth, with some people calling it the first Tyrrell!).

Photo: Peter Collins

The Vanwall story, however, was about far more than winning a crown for a constructor. Tony Vandervell, who headed up Vandervell Bearings, the world’s leading producer of thin shell engine bearings, was a fiercely patriotic man who desperately wanted to whip the Italians. The dominance of Alfa Romeo, Ferrari and Maserati in the postwar period really was a source of irritation to him and there were those who felt he hated the Italians (and all foreigners, in general). In many respects, this is too simplistic an explanation for the motives of a very complex man, but, in some part, it served to move him in the direction of joining the board of BRM in the late 1940s. BRM was going to build the Grand Prix car to finally vanquish the foreign hordes. However, the BRM project seemed doomed to disaster, and in the early 1950s, Vandervell lost patience and set out to develop his own team.

Tony Vandervell was a cagey customer, and though he clearly had his sights on running his own Grand Prix team, he didn’t want to ruffle too many feathers at the BRM organization. In addition, he was the supplier of his bearings to companies such as Ferrari, and he wanted to keep his customers. He also wanted to make use of these contacts, and thus he entered into a deal whereby a Ferrari would be purchased and run as the Thin Wall Special, a sort of mobile test bed for the company’s bearings. In reality, it was Vandervell’s clever way of breaking into Formula One without upsetting the establishment and getting very valuable experience for the future. It wasn’t long before the Ferraris were abandoned for his own Vanwall Special, which then became the Vanwall and went on to be a very powerful force in racing.

VW14

When Vandervell achieved all his aims in motor racing at the end of 1958, he decided to retire the team. This decision was also partly precipitated by the death of Stuart Lewis Evans in the final race of the year, and it took some of the lustre off of the team’s accomplishments. After half-heartedly preparing one car for Brooks for the 1959 British Grand Prix, the team built two new chassis, but then only appeared once more with the front-engine machine at Reims in 1960. As Vandervell had held onto all the cars, these things were possible, as no cars were sold off to privateers.

Then along came 1961 and the new rules. In addition to the Grand Prix formula for 1.5-liter cars, there appeared another international category known as the Intercontinental Formula, which allowed up to 3-liters. This was seen as a series that might tempt some American teams into the arena. The British teams were very much against the 1.5-liter rules and believed the crowds would happily support the larger engine alternative, and indeed there were a few good races in the first half of the 1961 season.

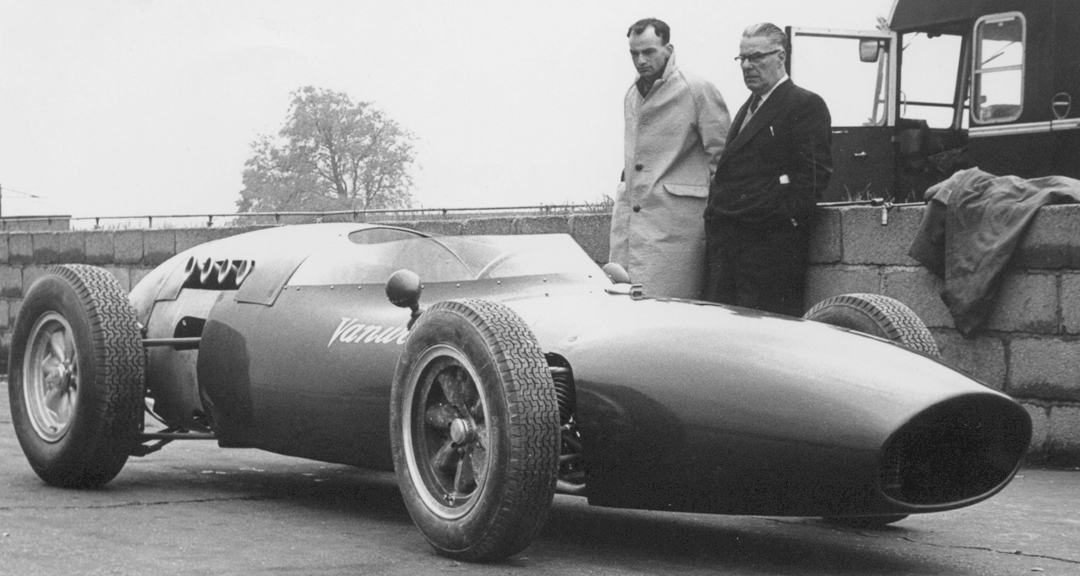

For reasons which are not entirely clear, Vandervell gave the “OK” for the construction of a rear-engine car for the Intercontinental series. After the team’s experience with Colin Chapman and Frank Costin making the front-engine Vanwall so fast and aerodynamic, there was a lot of knowledge at Vanwall. In 1960, a Lotus chassis (Lotus 18 chassis 901) was used with an enlarged 2.6 engine in the rear. This was known as VWL12 and was used for test purposes only. In 1961, with some thought that the Intercontinental series might be successful but with no real plan for a season’s racing, VW14 was built, using slightly modified versions of three engines from the earlier cars and adapting them for rear-engine usage.

In reality, VW14 probably had about as short a racing career as any car can. Back in 1958, Tony Vandervell met John Surtees and asked him if he would like to try a Vanwall. Surtees was polite, but nothing came of it at the time. Vandervell was very keen on motorcycles and indeed was a director of Norton, from whom the Vanwall engine was derived. In simplest terms, a Vanwall engine is four Nortons!

Photo: Peter Collins

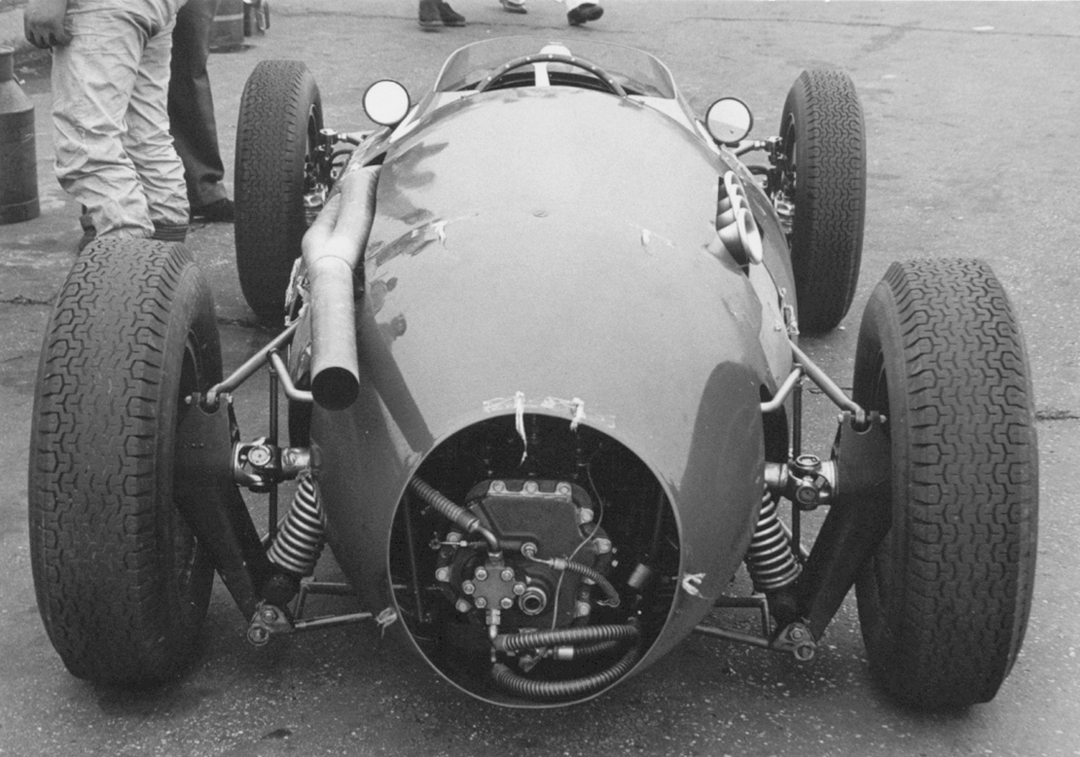

After Surtees tried the Aston Martin Grand Prix car in 1959, Vandervell reminded Surtees that he had offered him a drive, so Surtees did 170 laps at Goodwood in a front-engine car, equalling the fastest times the car had done there. It was not too surprising then that Surtees should be invited to try the rear-engine car in its debut outing in The International Trophy at Silverstone on May 6, 1961. The International Trophy was the third race in the Intercontinental series and had the best grid to date with Moss, Brabham, Clark, Graham Hill, McLaren and Roy Salvadori. Surtees qualified a creditable 5th on the grid and already thoughts at the Vandervell factory focused on a rear-engine return.

At the start on an extremely wet track, Brabham, in a Cooper, led McLaren and Moss, also both in Coopers, followed by Surtees, in the dark green Vanwall. Surtees pushed past Moss at an early stage into third, but was demoted again. Moss got past Brabham on lap 23 and disappeared into the distance. Surtees then got by the gritty Brabham into second until he spun at the fast Abbey corner and was forced into the pits to remove mud and grass from all the car’s orifices. In spite of this, a determined John Surtees went out and fought back up to 5th. But that was how it ended, and that was the last appearance of a Vanwall in a race.

VW14 today

Shortly after the Silverstone race, Jack Brabham did a test session with the car, but it then went back to join the other Vanwalls in Tony Vandervell’s Acton factory in London. When the Vanwall collection was sold off, most of the cars went to Tom Wheatcroft’s Donington Collection, including VW14. The car had been tried in two body formats, one with an enclosed nose, before returning to the more traditional open nose of the period.

Tom Wheatcroft, as we have said in these pages before, is a larger-than-life character and is responsible for returning Donington Park to being a great race circuit and for the world’s largest collection of Grand Prix cars, including several of the Vanwalls. Tom occasionally runs what he calls one of his “play days,” when he takes a handful of cars from his collection over to the track to give them a run. One sunny day last summer, I was asked if I wanted to come, and out came the P34 6-wheel Tyrrell, VW2 – a very early front-engine Vanwall – the Lancia D-50 and VW14. Tom, his son David and Rick Hall had a run in some of the cars. I was supposed to try the D-50, but that became impossible, so Tom said, “Try what you like, lad!” I opted for VW14.

John Surtees raced it once. Jack Brabham did some test laps, and Tom did a few laps. Tom said he thought I would enjoy this and should “get on and see what she’ll do.” You don’t get an order like that very often.

The car had been dubbed the “Whale” back in 1961, and Surtees had referred to it as “The Beast,” largely in reference to its rather skittish handling tendencies in high-speed corners. Although there had been rumors that Vanwall might develop a 1.5-liter car, nothing much more happened other than a bit of tweaking to the suspension before VW14 went into retirement, and Vandervell concentrated its research and development on improving bearings.

The car is thus very much as it last ran in 1961, and in 2002 it doesn’t look at all like a “whale” or a “beast” but an attractive and extremely neat execution of the rear-engine Grand Prix car.

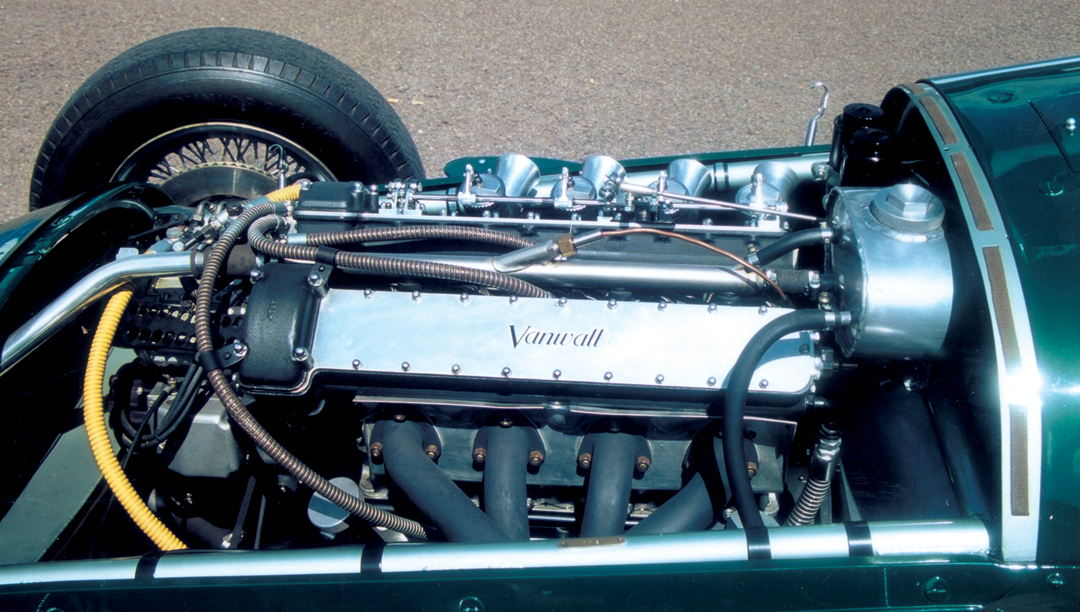

Sitting behind the driver in this car, however, is an engine unlike its contemporaries in many ways. Vandervell’s connection with Norton and his belief in what four 500 cc units could do was the basis of all Vanwalls. By 1955, Leo Kusmicki had taken Norton engine development on a long way, and an effective camshaft design allowed the possibility of using a Bosch fuel injection system, with the injectors for the system linked to the bodies and throttle slides of four Amal carburetors. This produced considerable power and reliability. By the time the engine was in its final stage in 1958/59, it was putting out 290 bhp.

The Vanwall’s unusual layout has two overhead camshafts, each carried in a separate housing on pedestals, with the valve springs and hairpin return springs exposed to the air for cooling. It takes some getting used to, and looks for all the world like the mechanic forgot to reassemble the engine! It does mean also that there is going to be some oil about. Ignition is by magneto and two plugs per cylinder. Not surprisingly, the crankshaft turns in Vandervell Thin Wall bearings.

The Chapman/Costin inspired light space frame of the front-engine cars is retained in VW14. The same five-speed gear cluster with synchromesh on the top four gears is also fitted.

Driving the rear-engine Vanwall

Tom Wheatcroft had a half dozen laps purely for the joy of driving, taking it fairly easy after some harder lappery and a spin or two in his magnificent Lancia D-50. VW14 was left to me to peruse and reconnoiter, a little known car pretty much ignored by the journals of 1961, in spite of it representing a possible return to racing by Vanwall.

Vanwall is scripted tidily across the cam covers on this unique engine, and a tour around the back reveals that the gearbox is well aft of the car. One might think this is going to mean oversteer, however Tom reports a slight tendency to understeer into slower corners – though he admitted to not using a lot of throttle. The interior features a simple cloth-covered seat, but a key focus of attention is the way in which the steering column gets down amongst the pedals. There will be no left foot braking here! The gearbox, once the four-cylinder barked into life, required firm handling and a sure sense of direction, but was completely unproblematic after that. First gear is left and back, and forward for reverse, fortunately these two gears lock out for safety, with the rest of the pattern being a normal “H.” The three-spoke steering wheel feels thin for a Grand Prix car, but this is 40 years old after all. The rev counter reads to 8000 rpm, and I was asked to use 7000 and only proceed to 7500 with caution. I suspected I might never get that far anyway.

There are the usual instruments, all within a good line of sight. The cockpit is relatively wide, and I could sink down into it; whereas Tom, who is rather tall, found himself being buffeted about. As the water rails run at shoulder height, you try not to lean on them too much. There is a fuel tank at either side and one at the front as well, with a filler in front of the screen.

Grip is provided by Dunlop Racing 500 L 15 on the front and 6.50 L 15 at the rear. The interesting thing about your perception from inside the car is that the nose and shape look distinctly Vanwall, as it does from the front. The Costin look and attention to cleanliness has been carefully carried over into this car. To my surprise, there was more immediate torque apparent than all my reading had led me to expect. This is not wild torque but provides a smooth sense of power. As soon as you put your foot down, the 2.6 engine pushes you away. The lovely exhaust is two sets of two pipes joining as one just behind the driver’s left ear and gives a good account of what is happening in the engine. My biggest concern was what those narrow tires would be like turning into medium corners. However, that caution induces a smooth approach, and that is what this car likes.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

John Surtees may have found it twitchy in the wet; but here, on a dry and warm Donington, grip was good, and within a few laps, I could maintain a higher gear through Redgate, keep my foot flat down through the wonderful Craner Curves and hold it flat…..well nearly……all the way to the old hairpin. While this corner could force you down to second, keeping the revs up and staying smooth, it could be taken hard and fast in third, then up to fourth as the Vanwall winds its way up to McLeans. Under some pressure, the understeer goes, turns to fabulous tail-out oversteer – all very manageable. The narrow tires in the line of sight keep telling you not to overdo it in the turns, and a fast exit is possible onto the straight, up to top gear at 7000 rpm and managing to get to about 6400 in top. That’s pretty quick….maybe 145 mph, but it’s not the speed that’s impressive but the fantastic friendliness of the drive.

This is my first ever run in a 2.5-liter Grand Prix car and I am beginning to go quickly. Three, four, five laps go by and each corner can be taken a bit faster, with the braking being left later. There is no brake fade, and they remain totally smooth, provided they are not overused. This is classic driving…in slow and out fast, keeping the revs as high as possible. All the concentration is on letting the car slide, but not scrub off speed. I am amazed the tail doesn’t want to break away. Twelve laps go by and all too soon it is over. I am full of regret that somehow Tony Vandervell didn’t get inspired by the new age of rear-engine racing cars. Given Surtees’ performance in an untried machine, and the power of the unique Vanwall engine, this car certainly could have done well in the remainder of the Intercontinental series. That series, by the way, died the death. The harbingers of doom, who said the 1.5-liter formula would be terrible, soon saw the smaller cars running quicker than those with an additional liter of displacement. Perhaps the Vanwall engine would never have gotten down to 1.5 liters, but it would have been nice to see it try.

Buying and owning a Vanwall

Well, that’s pretty simple. Vanwalls don’t come on the market so you would have had to buy one in 1986 when Tom Wheatcroft got most, if not all, of them. However, maintenance means it helps to have a museum. In the course of our “play day,” the gearbox broke on VW2. That means lots of rare parts will have to be made. Fortunately for Tom, Rick and Rob Hall look after the cars and have done most of the upkeep and restoration when needed. What is required is an in-depth knowledge of the cars, especially something like these Norton-based engines. Given the rarity of the cars, it is almost impossible to put a price on them. The front-engine cars of 1956-58 would bring a fortune, but VW14 is a bit of a mystery. Somehow, I don’t think we will see that on the market anyway. Thanks, Tom.

Photo: Peter Collins

Specifications

Chassis: Tubular space frame

Wheelbase: 7’ 6.25”

Track: Front: 4’ 5.75”, Rear: 4’ 3.75”

Weight: 1200 lbs approx.

Engine: Four cylinder, in-line

Capacity: 2596 cc

Valvetrain: Twin overhead camshafts operating 2 valves per cylinder

Fuel: Bosch fuel injection

Power: 290 bhp @ 7300 rpm

Transmission: Five-speed gearbox in unit with final drive

Brakes: Vandervell-Goodyear disc brakes

Tires: Dunlop Racing

Resources

Jenkinson, D. and C. Posthumus

Vanwall

Patrick Stephens, Cambridge, 1975 ISBN – 0 85059 169 4

Lawrence, M.

Grand Prix Cars 1945-65

Motor Racing Publications

Surrey, UK 1998

ISBN – 1 8998 70393

Posthumus, C.

Classic Racing Cars

Optimum Books, London, 1981

ISBN – 0 600 35003 7

The generosity of Tom Wheatcroft and the Donington Collection is gratefully acknowledged.