You wouldn’t need all the fingers of one hand to count the number of men who could beat Juan Manuel Fangio around the daunting Nordschleife of the Nürburgring, but one of them was certainly a suave German named Rudolf Uhlenhaut. Strangely, he wasn’t a racing driver at all but a hyper-talented engineer who taught himself to drive state-of-the-art racing cars like the professionals. Not in the way that racing drivers of his day graduated through the lower ranks of their sport – motorcycles, saloon cars, grand tourers and so on – to the pinnacle of Formula One. Uhlenhaut, who never actually owned a car in his life, started from zero and taught himself.

As Uhlenhaut often remarked, however, driving such a hairy beast was not so difficult. Going fast in it was the difficult bit. And learning to do that was hard work.

Why go to all that trouble? Well, in 1936 at just 30 years of age, Rudolf Uhlenhaut was appointed technical director of the Mercedes-Benz racing department. His professional drivers were unable to tell him what a car did right or wrong and why. So, Uhlenhaut decided the only real way to find out was to learn to drive the cars at racing speeds himself.

The sophisticated Uhlenhaut, who spoke perfect English, was the man behind the all-conquering Silver Arrows of 1937-1955. Now that kind of pedigree ought to be enough for any man, but Rudolf Uhlenhaut worked hard at directing the technical side of the Mercedes-Benz racing department and learning to drive the cars he and his men designed. He worked so hard and was so talented that he even beat Juan Manuel Fangio’s time around the ’Ring by more than three seconds!

He never raced, however, and often wondered how he would fare in the heat of battle against the Auto Unions of the ’30s or the Ferraris and Maseratis of the ’50s. He had the technique, but it had only been put to the test when the tracks were empty.

This genius of a man was born on July 15, 1906 in London, where his father was a top executive of the Deutsche Bank. Banking was not for Rudolf, though. He was fascinated by machines and how they worked. Unlike many youngsters of his day, he did not want to drive steam engines, he wanted to design them.

He graduated in engineering from Munich University in 1931, the year he also joined Mercedes-Benz, after which trains gave way to cars as the love of his life. Germany was in the grip of an economic depression at the time, but the good news to Uhlenhaut was that he went to work in the company’s experimental department: the bad news was he was paid only half the wages of a skilled laborer when he did so. First, he worked on developing carburetors, but later moved to road cars. That meant he often took the new Mercedes-Benz sedans to the Nürburgring for testing, and there he drove them flat out. Toward the end of the 1936 season, when the company withdrew their uncompetitive W25 from motor racing, the directors cast around for an established engineer to become technical director of the racing department, but there were no takers. If results were poor, the technical boss’ career tended to be short.

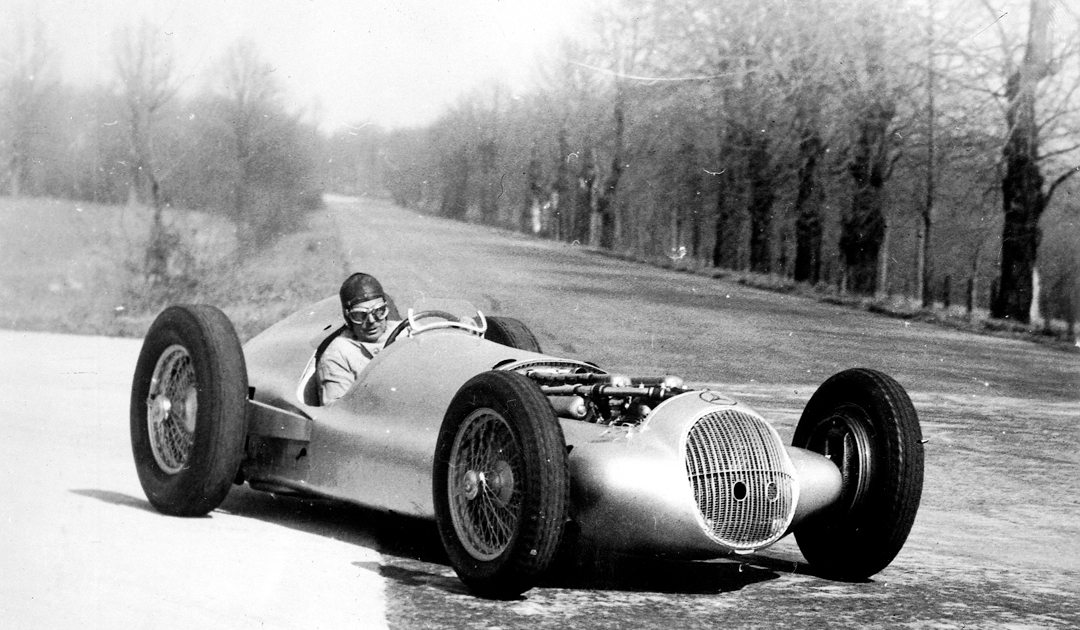

Eventually the board offered the job to 30-year-old Uhlenhaut and he took it. At the time, nobody in the department could drive a racing car, so they had to rely on the often inarticulate comments of the professional drivers. No way was that good enough for Uhlenhaut, so he had two W25s taken to the Nürburgring, where he began the long, hard process of learning how to drive them fast. Literally thousands of miles later, he had become so good at hammering around the ’Ring, Hockenheim and even Monza that he could beat people like Caracciola and Luigi Fagioli at their own game.

In actual racing, however, he let his drivers do the winning in cars like his low-slung 1937 Mercedes-Benz W125, which was the last of his company’s 750-kg formula racers. It was an 8-cylinder 5663-cc fireball that put out a whopping 592 hp and had a top speed of 200 mph, just right for the AVUS Grand Prix on those two autobahns joined at each end by sharp curves, one of them steeply banked. Ex-mechanic Hermann Lang gave the car its debut win there. His W125 gobbled up the race’s 97.3 miles in 35 minutes 30.2 seconds for an average speed of 162.61mph, but it was Rudolf Caracciola who won the 1937 German, Swiss and Italian GPs in the car and scored high placings in others to become European Champion for a second time.

For 1938 the team had the choice of developing either a 3-liter supercharged, or a 4.5-liter unblown engine. Mercedes-Benz had already gathered considerable experience in supercharging going back to the victorious 1924 Targa Florio car, so Uhlenhaut decided to tread the same path for 1938. He came up with the 3-liter V12 W154, the chassis of which was similar to its predecessor, but a little shorter to accommodate two fuel tanks to feed the thirstier engine. The W125’s tanks held 55 gallons, but the W154’s took 88. Fuel consumption of the 485-hp car was a zonking 140 liters to every 100 kilometers.

The W154 just ripped through the opposition, its supercharger keeping up a constant, almost terrifying screech as it went, winning six of the nine European Championship Grands Prix—they included Dick Seaman’s famous victory in the GP of Germany—and earned Caracciola his third and final title.

Some jiggery-pokery was afoot, however. Not until Monza in September 1938 did Uhlenhaut discover the Italians were so tired of being beaten by the marauding Silver Arrows that they were going to change the rules of “their” Grand Prix of Tripoli, which Mercedes had won in 1935, ’37 and ’38. The Italians’ plan was to admit only cars of up to 1.5 liters, knowing full well that the Germans had no such machine, but the devious little ploy backfired. Unknown to the rest of the world, Rudolf Uhlenhaut and his colleagues quietly went to work designing, developing and building two 1492-cc, 187-hp W165s especially for the Tripoli showdown. Incredibly, they went from being an idea in Uhlenhaut’s head to two finished cars in under eight months.

As Uhlenhaut was testing the first W165s at Hockenheim, Lang was winning the 1939 season’s opening Grand Prix at Pau on April 2 in a W154. Still not a whisper had reached Italian ears about the secret W165, now successfully tested, so jaws dropped as the two completely unexpected 1492-cc Mercedes W165s turned up at Tripoli’s Mellaha circuit just in time for practice. The Italians were flabbergasted, but not as much as when Lang won the race and Caracciola came 2nd in the new Wunderwagen, which never raced again. By season’s end, Mercedes had racked up six European Championship GP victories out of a possible eight, and Hermann Lang had won the title.

After that, motor racing stopped as the Second World War took over.

By 1950, Mercedes-Benz motor racing boss Alfred Neubauer was lobbying his company’s management to get back into racing—and he succeeded. So Rudolf Uhlenhaut, who was designing road cars at the time, was asked to come up with a sports racing car based on standard production car parts. The result was the 1952 300 SL, the famous 2996-cc, 170-hp gullwing in which Karl Kling won, Lang came 2nd and Fritz Riess 3rd in the Bern Prix in Switzerland. Lang and Riess then won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in the car, and Lang won the Nürburgring Jubilee Grand Prix with Kling 2nd and Riess 3rd. Then Kling scored his famous victory in the Carrera Panamericana, with Lang 2nd. A sensational year for a sensational car.

Mercedes-Benz was back, and its board decided to compete for the two top motor racing titles: the Formula One and World Sports Car Championships. Uhlenhaut and his team went to work again, this time without having to resort to production basics, and created the thoroughbred W196 single-seater in open-wheel and streamlined versions for F1, plus the 300 SLR for the WSCC.

Uncharacteristically, the W196 was late arriving. Juan Manuel Fangio had been contracted to drive the car from the beginning of 1954, but was given a special dispensation to campaign a works Maserati 250F so that he could score World Championship points from the outset; he won the Argentine and Belgian GPs in the Italian racer.

The W196 was ready for the Grand Prix of France at Reims, where there was a communal gasp of amazement as three seductively curvaceous streamliners were unveiled. Fangio won and Kling came 2nd in rather battered cars, whose sensuously sculpted bodywork obscured the drivers’ view of the corners. Marker drums went flying as the drivers strained to peer over the arched front fenders, but still the 2497-cc 8-cylinders led the field from start to finish. The open-wheel W196s were used for most of the remainder of the season, in which victories in the French, German, Swiss and Italian Grands Prix earned the Argentine his second world title.

Stirling Moss joined the team for 1955 and spent the year driving in Fangio’s wake in all but the British Grand Prix, which he just won from his hard-charging teammate. The two drove so closely together that they were called “The Train,” at the head of which Fangio won his third World Championship. Moss was more successful in Uhlenhaut’s elegant new 2981-cc, 180 mph 300 SLR sports racer, though. The Briton set the fastest time ever in the 1955 Mille Miglia by covering the 993.32 miles at an average speed of 97.96 mph, a record that still stands today. He and Peter Collins gave Mercedes the year’s World Sports Car Championship with their spectacular win in the last round in the series, the Targa Florio.

After the withdrawal of Mercedes from racing at the end of 1955, Uhlenhaut became head of Mercedes-Benz research. One of his many gifted developments was the series of futuristic C111 mobile laboratory cars from 1969, on which Mercedes experimented with rotary and diesel engines and turbochargers. Many of his ideas came to life and were built into their road cars for years to come.

Rudolf Uhlenhaut retired in 1972 after a spectacularly successful career and split his time between his handsome villa on the outskirts of Stuttgart, skiing in Davos, Switzerland in the winter and his Malta-based yacht during the summer. He died in May 1989.