1959 Cooper T-51 and 1960 Cooper T-53

The two Formula 1 Coopers you see here represent one of the key moments in the evolution of Grand Prix racing. From the beginning of the Drivers’ Championship in 1950, front-engine cars were the norm. Through the years of the 2.5-liter engine formula, Ferrari, Maserati, Mercedes, and Vanwall dominated. The British Vanwall rose to the pinnacle during the first year of the Constructors’ Championship in 1958 and took that title. Enzo Ferrari proclaimed that Grand Prix cars would always be front-engined. “You wouldn’t put the donkey behind the cart” was his view.

But behind the scenes, there was a shift going on in the “lesser” formulae, and the 500-cc F3 category was becoming largely the province of John Cooper and his father Charles Cooper with their peculiar looking little cars. But in F1, it took a long time before most people took rear-engine design seriously, and that was in spite of the huge prewar success of the Auto Union. Despite the presence of the odd Cooper in F1 toward the end of the ’50s, as 1958 came to a close with Vanwall glory, there is limited evidence that serious consideration was being given to “turning everything backwards”…except by the Cooper father-and-son team.

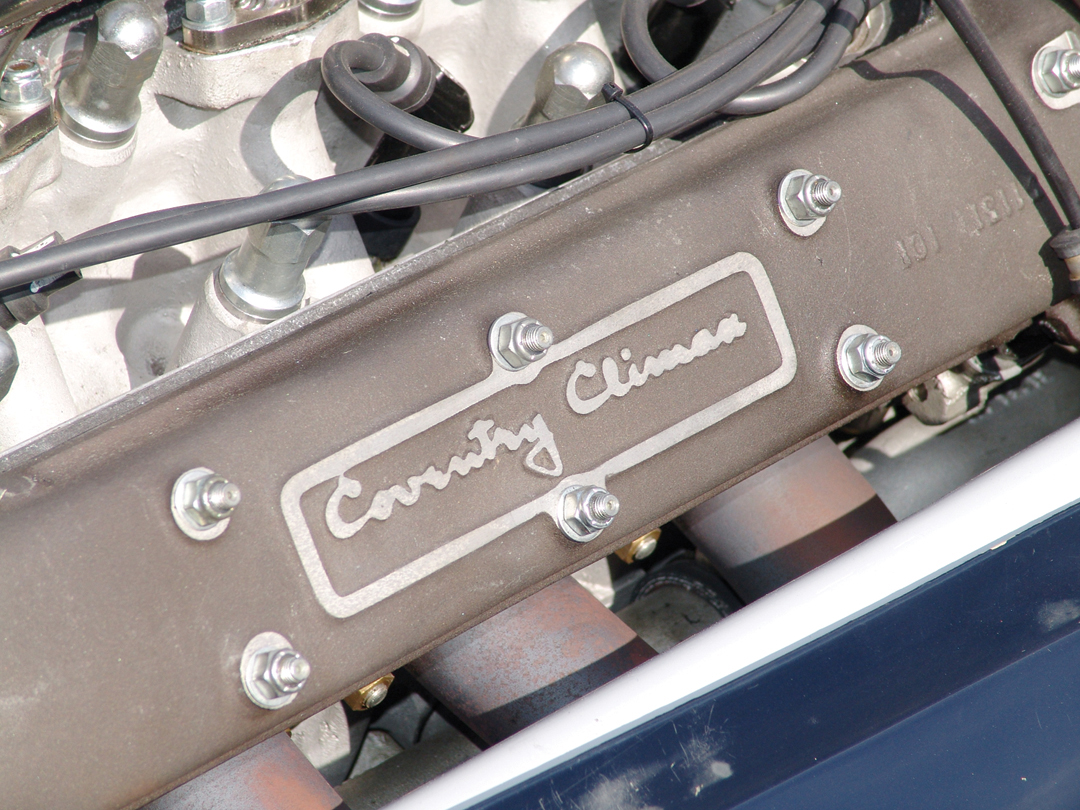

By 1956, the Coopers had put a Coventry-Climax 1,100-cc engine into one of the Mk. IX 500-cc chassis, then improved it, and pared down the bodywork, turning it back into a single-seater, the first Cooper F2 car. Then Coventry-Climax produced a 1,500-cc engine, which the Coopers set to enlarging. This, in combination with a modified Citroën gearbox (with French ERSA 4-speed internals), worked very well. During 1957, Coventry Climax moved from a single to twin-cam layout, Citroën internals replaced the ERSA parts in the gearbox, and engines were available at 1,475, 1,960 or 2,200-cc displacements. The 1958 version saw the standard transverse leaf spring suspension with lower wishbone at the front disappear, to be replaced by a coil and unequal wishbone set-up, with adjustable Armstrong shock absorbers in the coils. An easily removable antiroll bar, running through the frame cross-member, also appeared in this updated version. In the rear, the leaf, which laterally located the rear spring, was replaced by a lateral link. There were also improvements to the gearbox, a new casting featuring step-up gears to make changes smoother. When the Cooper won the first two Grand Prix races in 1958, the development of a full 2.5-liter Coventry-Climax became a priority under the eye of Wally Hassan, though it took rather longer than expected to appear. These first two races, the Argentine and Monaco GPs, were won by the Rob Walker team of Moss and Trintignant, in 2-liter cars.

Because the 2.5-liter Climax was slow in coming…pardon the pun…teams tried Borgwards, Maserati, and even BRM engines. The problem both the works Cooper team and the privateers had was finding a gearbox which could handle the increasingly available power. Cooper developed a new and tougher case for the works cars. They also had larger 6.00-inch tires at the rear, and with new upper wishbones, could adjust the camber more easily.

Rob Walker’s R.R.C. Walker Racing Team had a number of Coopers at the beginning of 1959, including the T-51 model, and Valerio Colotti was engaged to design and build a 5-speed gearbox for these cars at his TecMec Studio in Modena. This was built in four months and showed promise, but ended up with severe reliability problems. In the end, it was discovered that parts of the gearbox had not been correctly machined to Colotti’s specification, but it took a long time to discover this.

The T-51

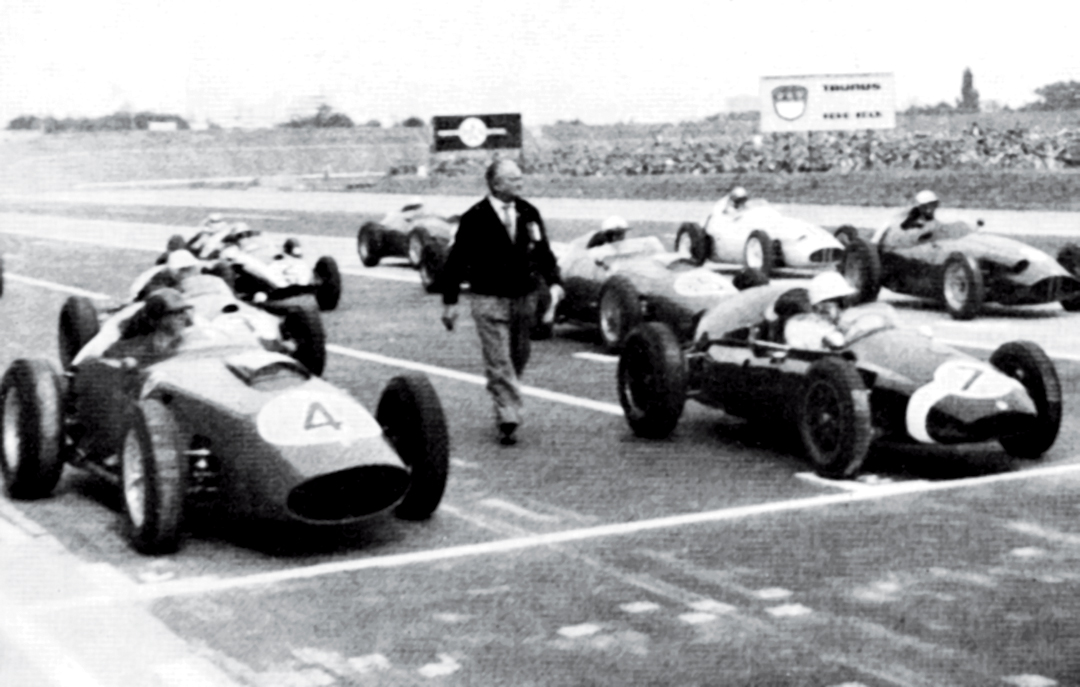

The Rob Walker team had entered six F1 and ten F2 races in 1957. While theoretically Ferrari looked very strong for 1958, the number of Coopers had increased, mainly on the basis of low cost and easy maintenance. The Walker team began to pay more attention to F1, running in 12 events, as well as taking part in eight F2 races. But the sensation for Rob Walker and Cooper was Stirling Moss’s sensational win at the Argentine Grand Prix in January. The field was small, but consisted of three works Dino Ferraris, a batch of Maserati 250Fs, including one for Juan Fangio…and one little, rear-engine Cooper T43 F2 car with a 1.9-liter Coventry-Climax engine…the Rob Walker entry for Stirling Moss.

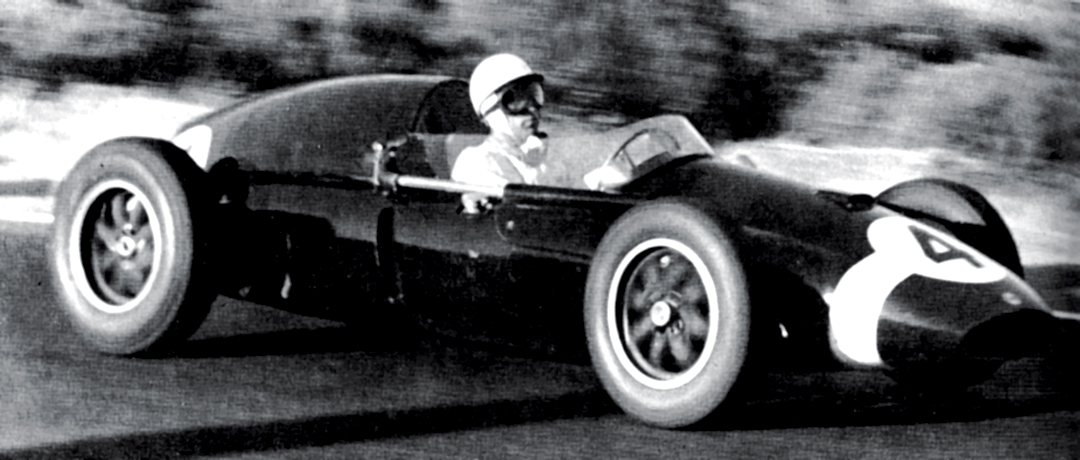

Moss was two seconds slower than Fangio in practice, 7th fastest in the small 10-car field. Moss started slowly but worked his way into the lead, but Musso was right behind after his tire stop, and as he passed the pits he saw the mechanics roll out new tires for Moss’s car, so wasn’t worried. It was a trick. Moss could see the canvas showing through on the tires but didn’t stop, and as a result won. Maurice Trintignant gave Walker another giant-slaying win at Monaco though that was a circuit much more suited to the Cooper. Moss swapped to Vanwall for Grand Prix races, but took two more nonchampionship victories for Walker in a Cooper.

For 1959, Ferrari still thought, without Vanwall, it had a good chance against the hordes of Coopers that Charles and John were selling to private teams. Even when the 2.5-liter Climax would appear, it would still have 30 bhp less than the Ferraris, which would certainly dominate on the fast, wide-open circuits. And Ferrari had a very impressive driver lineup for 1959 consisting of Tony Brooks, Jean Behra, Phil Hill and Dan Gurney.

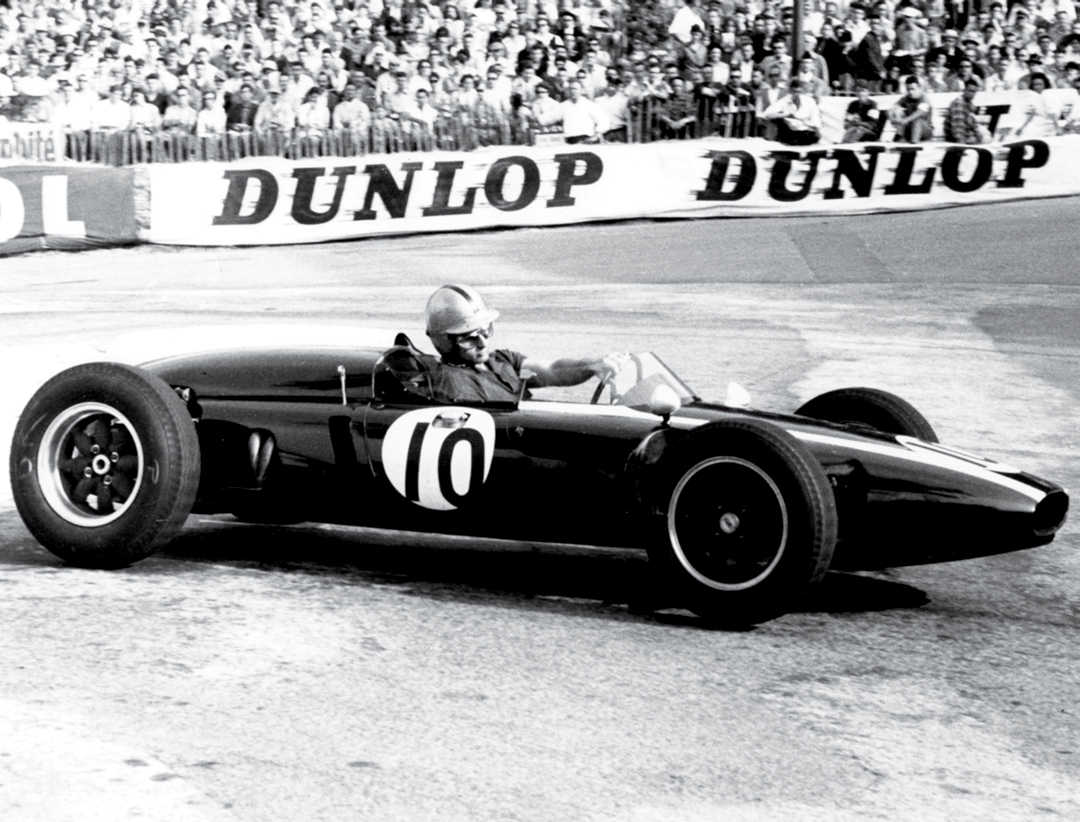

Moss took the opening nonchampionship race at Goodwood with Rob Walker’s first T-51, while Jack Brabham won the International Trophy at Silverstone in a works T-51. Roy Salvadori was 2nd in the new Aston Martin F1 car, providing a little hope for the new car but that would turn out to be a futile hope. Brabham then won the first championship round at Monaco, though Tony Brooks was not that far behind in a Ferrari. Moss had led but retired with 20 laps to go. Then Jo Bonnier gave BRM something to think about with his famous victory in the Dutch Grand Prix, in the front-engine P25. Moss managed to lead before the Colotti gearbox broke for the second time. A season-long battle for the drivers’ title had begun between Moss, Brabham and Brooks.

When the cars arrived at Reims for the French Grand Prix, the purists felt that tradition would be restored and that the Ferraris would disappear on the long straights. They got something of a shock in practice when Jack Brabham’s T-51 Cooper was only a fraction slower than Brooks’ pole-winning Ferrari. He was 15 bhp down but the Cooper’s advantage became apparent…it had a much smaller frontal area, and therefore less resistance. The weight balance had also been sorted out so it was quicker than expected on the straights, and very quick in the corners. It weighed less than the front-engine cars, and the drivers were cooler because the engine was behind them, though this was relative as it was very hot that day in France. Cooper had tried an aerodynamic body in practice but it lifted at the front so was put aside.

Stirling Moss was driving the BRM for two races, and his retirement in France probably cost him the championship. The Ferraris of Brooks and Phil Hill won, with Jack Brabham’s works Cooper in 3rd. The front-engine cars had done what was predicted on the fast Reims track, but Cooper had delivered a message…the car was not that much slower on the so-called “Ferrari tracks.” Jack Brabham then won convincingly at the British Grand Prix at Aintree, with Moss in the BRM 2nd and Brabham’s Cooper teammate Bruce McLaren in 3rd.

Moss was back with Rob Walker for the German Grand Prix, which was being held at the super-fast banked A.V.U.S. track in Berlin. Walker had acquired a new Cooper T-51 for Moss, chassis F2-19-59, one of the two cars you see here. He also entered the older car for Trintignant.

This race goes down in history for the terrible, fatal crash of Jean Behra in a supporting race, after he had left Ferrari under very acrimonious circumstances following the French Grand Prix. Tony Brooks was on pole in the Ferrari, though Cliff Allison was quicker, but started at the back because he was a reserve driver. The event was run in two heats and results would be decided on aggregate. Stirling Moss had F2-19-59 next to Brooks on the front row, thus the Cooper was again seen to be not that much slower than the more powerful Ferrari. However, Moss had his gearbox break yet again. Not coincidentally, it was about this time that Moss got something of a reputation as a “car-breaker,” though it wasn’t until much later that it was discovered that the gears had been incorrectly machined. Brooks won both heats and was the victor on aggregate from Dan Gurney and Phil Hill. This would, however, be the last 1959 win for a front-engine car. Trintignant brought the other Rob Walker car into 4th spot.

F2-19-59 more than compensated for its disappointing performance in Germany by spectacularly winning the next three F1 races. Stirling Moss had won the F2 race at Clermont-Ferrand in Walker’s Borgward-powered Cooper just before the A.V.U.S. race and was seriously enjoying the way the Coopers handled. While Moss would later say that the Lotus was more responsive and more likely to win, the Cooper was a more enjoyable car to drive.

Stirling Moss would certainly enjoy driving F2-19-59 at the Portuguese Grand Prix at Monsanto later in August. Monsanto was a true driver’s circuit and it suited Moss and the Cooper so well that they were a clear two seconds faster than Brabham in his works car which itself was a further second and a half in front of the hard trying Masten Gregory in another works Cooper. Trintignant was competitive in 4th qualifying spot ahead of Bonnier and the BRM, the first front-engine car. Bruce McLaren got the other, older works Cooper ahead of Gregory so that four Coopers were in the lead. Brabham tangled with Mario Cabral while lapping him on lap 23, and had a serious crash into a pole, and was lucky not to be badly hurt. When McLaren dropped out as gearbox problems hit the works car, Gregory motored on into 2nd where he remained, although even he was lapped by the flying Moss. F2-19-59 was having its finest and easiest run to date. Gurney got 3rd, though he punted Trintignant who was letting him past at the time. Moss set the fastest lap, and it was clearer and clearer that the days of the front-engine Grand Prix car were numbered.

A week later Moss was at the Kentish 100 at Brands Hatch for this F2 race, with the Walker Cooper-Borgward, but he had to give best to Jack Brabham and an amazingly on-form Graham Hill in a Lotus 16. Moss had a broken wishbone, but even with that repaired, he could not get past Hill.

After the Portuguese race, Brabham still led the championship with Brooks 2nd and Moss next, though not looking likely to catch up. Then the circus went to Monza for the Italian Grand Prix, where Ferrari would have expected to win at the beginning of the year, but now had doubts. By this time the 2.5-liter Coventry-Climax engine had improved and was generally reliable. In qualifying, it was a straight fight between Moss in F2-19-59 and Tony Brooks in the Ferrari Dino 246. Jack Brabham was next ahead of the Ferraris of Gurney and Phil Hill. Brooks had a piston break virtually at the start leaving the race between Moss, Hill, Brabham and Gurney, with Harry Schell in a BRM P25. Interestingly, BRM had brought along their new Type 48 rear-engine car for practice, thus having read the handwriting on the pit wall.

Phil Hill led many of the early laps, with Moss and Brabham having let the Ferrari stay in front. Everyone was being careful with their tires, and after 33 laps, all the Ferraris were brought in for new tires. Moss was left in the lead, and he drove a very smooth race. Phil Hill got the jump on Brabham, set fastest lap and was 2nd behind Moss. Brabham hadn’t done as good a job of conserving his rubber as Moss had done, since Moss seemed to have plenty in reserve at the end. Though Moss had closed the gap in the title chase, Brabham’s 3rd place gave him the edge as he chased his first World Championship.

The Rob Walker/Stirling Moss team’s winning streak continued at the nonchampionship Oulton Park Gold Cup later in September, when F2-19-59 won from Brabham’s works T-51 and Chris Bristow’s BRP T-51. Ron Flockhart’s BRM P25 beat Brabham at another nontitle race at Snetterton, which Moss missed, before the GP teams went to America.

The inaugural USGP would be the championship decider, with Brabham looking most likely to win the title. Moss would have to win and take fastest lap to claim the championship, while Brooks would have to win, set fastest lap, and have Moss and Brabham finish worse than 2nd. Needless to say, it was a tense situation! F2-19-59 had had a spell of speed and reliability, and Moss was three seconds faster than everyone in qualifying.

The fact that Harry Schell seems to have cut a corner on the long circuit and got onto row one proved to be fatal for Brooks’s hopes as he was rammed at the start and went straight into the pits for work. Moss led…for five laps…and then the gearbox gremlins returned and he lost the championship. Bruce McLaren won from Trintignant, moving Brooks back up to 3rd. He was 3 minutes behind at the end, the amount of time he lost at his stop…when he was ahead of Brabham. Brooks almost won the title. Brabham had run out of fuel and pushed the car over the line…but he was champion.

Stirling Moss drove F2-19-59 one more time, in practice for the 1960 International Trophy at Silverstone, though he didn’t race it. The car then was entered for Italian Giuseppe Maugeri for the Siracusa and Naples nonchampionship races in 1960, but didn’t show up. Maugeri crashed it during the London Trophy race at Crystal Palace but drove it to 10th in June at Brands Hatch in the Silver City Trophy. It was not exactly clear when Walker sold it to Maugeri as it seemed to be entered in some of these races by the British privateer, but it never had the glorious results Moss had given it…until John Harper started doing very well in historic events many years later.

T-53—The Lowline

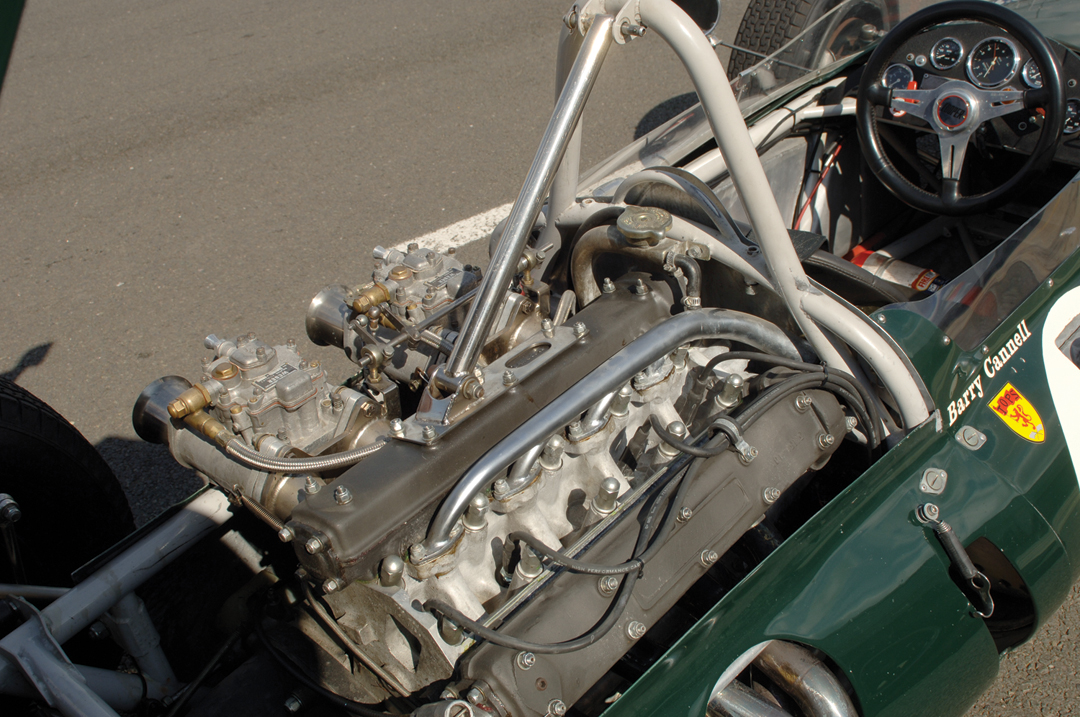

As this is being written, current owner Barry Cannell has just finished a very hard-fought and worthy 2nd place battle at the Monaco Grand Prix Historique, in FII-5-60. This is rather fitting, as this car made its racing debut at the Monaco Grand Prix on May 29, 1960, finishing 2nd in the hands of Bruce McLaren and setting fastest lap. In comparison to the Rob Walker T-51 Moss drove in 1959, this 1960 machine would have a much, much busier life.

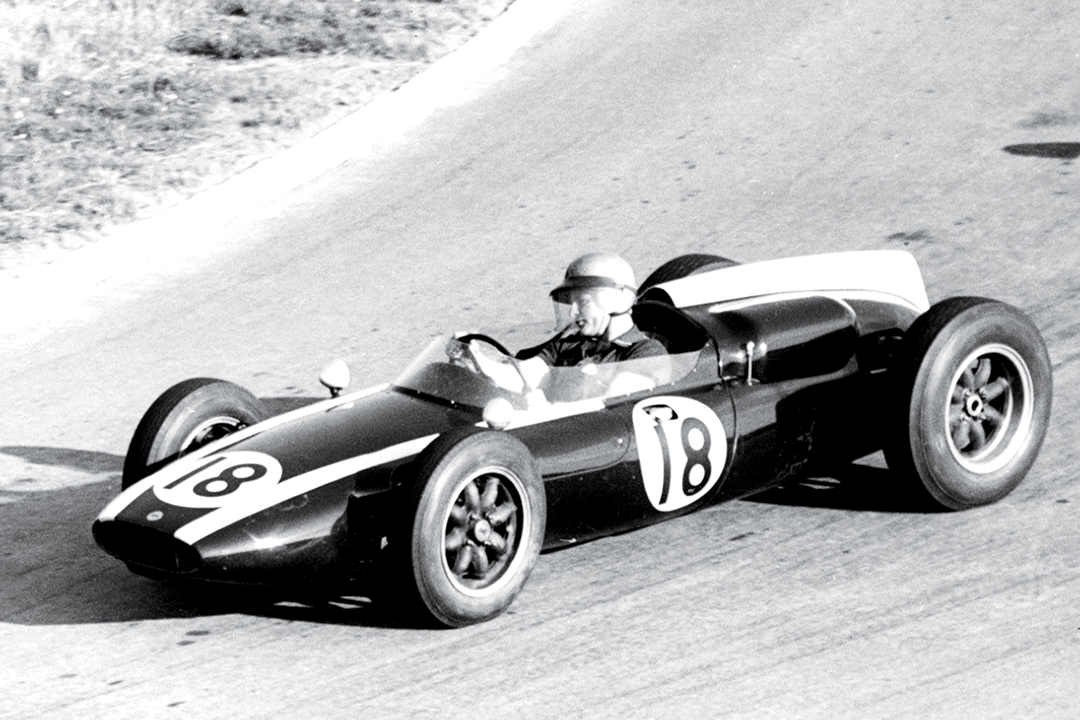

Bruce McLaren won the first race of 1960, the Argentine GP in an older T-51. Stirling Moss was on pole, but Innes Ireland was 2nd fastest and was very quick in the race until he spun and then had gearbox problems. Colin Chapman at Lotus had got the jump on BRM in the development of a rear-engine car, and the Lotus 18 was immediately fast. On the way back from that race, John Cooper and Jack Brabham decided they needed a new car. The combination of John Cooper, Owen Maddock, and Jack Brabham, with advice from Ron Tauranac, decided to move away from the standard Cooper curved-tube spaceframe. They decided to use straight tube, with added diagonal bracing tubes around the rear of the engine bay. The suspension mounting point locations and support joints were all well thought out. The result was that the frontal area was reduced. The engine was lower, the steering box was relocated forward and the cockpit was longer, allowing the driver to “recline”…thus the moniker “Lowline.” The result was a much sleeker car. There were wishbones at all corners and coil springs now replaced the transverse leaf at the back.

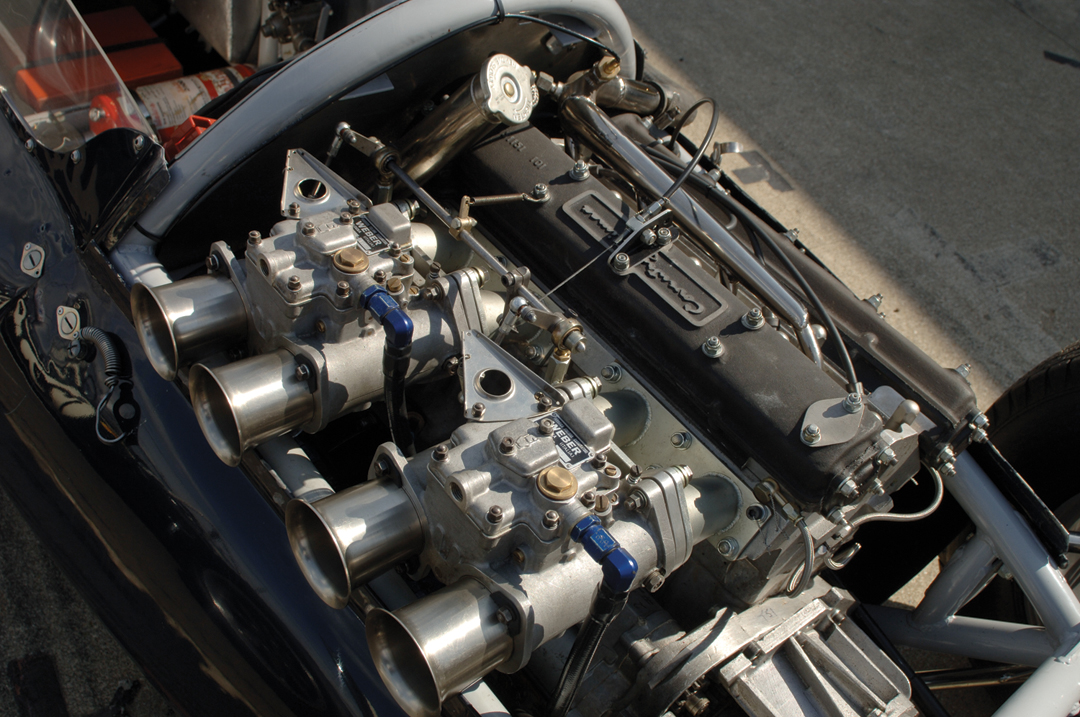

The Coventry-Climax unit was now producing 245 bhp, still 30 less than the Ferrari, though with loads of torque, and Cooper developed its own gearbox/transaxle. Early testing of a car that had only taken two months to build was very promising, though Ireland’s Lotus 18 beat them at the International Trophy at Silverstone.

At Monaco, Moss and Rob Walker had defected to the Lotus 18 ranks and was on pole from Brabham in his new works “Lowline” T-53. Bruce McLaren was down in 11th in FII-5-60, behind three Ferraris. One of these was in the hands of newcomer Richie Ginther…and now the engine was in the back…life at Modena had changed. It was an incredible race. Bonnier had the BRM P48 in front for a few laps before Moss took over. At the 30 lap mark rain fell, Brabham spun and was disqualified for a push start. Bruce worked his way up the field and had a great scrap with Phil Hill in the front-engine Dino. The skilled McLaren set fastest lap and got all the way to 2nd, nearly a minute behind Moss. Ginther was 6th, two Scarabs didn’t qualify, nor did Brian Naylor’s JBW-Maserati.

Bruce retired FII-5-60 at the Dutch Grand Prix, had another magnificent 2nd at Spa, and after this race was actually leading the World Championship with the car you see here. But Jack Brabham had the bit between his teeth and won the Dutch, Belgian, French and British races. Bruce was 3rd at Reims behind Jack, and 4th at Silverstone. The pair was proving that the choice to go “Lowline” was absolutely right. McLaren was then 3rd in the nonchampionship Silver City Trophy at Brands Hatch. He then took another impressive 2nd to Brabham at Oporto in this car and 4th at the Oulton Park Gold Cup. John Surtees was in a Lotus 18 in Portugal and was threatening. Most of the Brits missed Monza, which was being run on the full banking. Phil Hill drove his Ferrari Dino to victory, the last win for a front-engine car…everything had changed in two years.

At the USGP at Riverside, Bruce had his last race in FII-5-60, finishing 3rd behind the Lotus 18s of Moss and Ireland but ahead of Brabham, who took his second title in two years. Brabham then had eight races in FII-5-60 in 1961. He won the Lombank Trophy at Snetterton, retired at Pau, won two of the three heats at the Brussells GP, was 5th at Solitude, retired at Karlskoga, was 2nd in one heat and retired in the other at the Danish GP, 5th at the Modena GP and 2nd at the Flugplatzrennen in Austria. These were all nonchampionship races. Jack and Bruce had T-55s in the Grand Prix races, but the Coopers were eclipsed by Ferrari. The best 1961 result was a 3rd for Bruce at Monza.

Arthur Owen then took over FII-5-60 for the British Hill Climb Championship and scored wins in 1962–1963, with the car continuing to hillclimb for several years. It also went through John Harper’s hands, to Spencer Flack and then to Barry Cannell in 2002, where it remains very successful in his hands.

Driving Two Super Coopers

Occasionally we get rude messages from readers who deplore what an easy life we have, driving sensational cars, which most people can only dream about. Well, get set to start writing again. When we set about putting together a suitable Cooper celebration article, we went looking for cars which represented that significant moment in motor racing history, when Cooper was on top. John Harper and Barry Cannell, both long-standing and respected historic racers, responded to the appeal. Why not try a back-to-back test with Stirling Moss’s winning Rob Walker car from 1959 and the works Cooper Bruce McLaren raced in 1960, and that Jack Brabham ran the following year? These two cars truly symbolize the swap from front- to rear-engine cars in Grand Prix competition and Cooper at their championship-winning zenith.

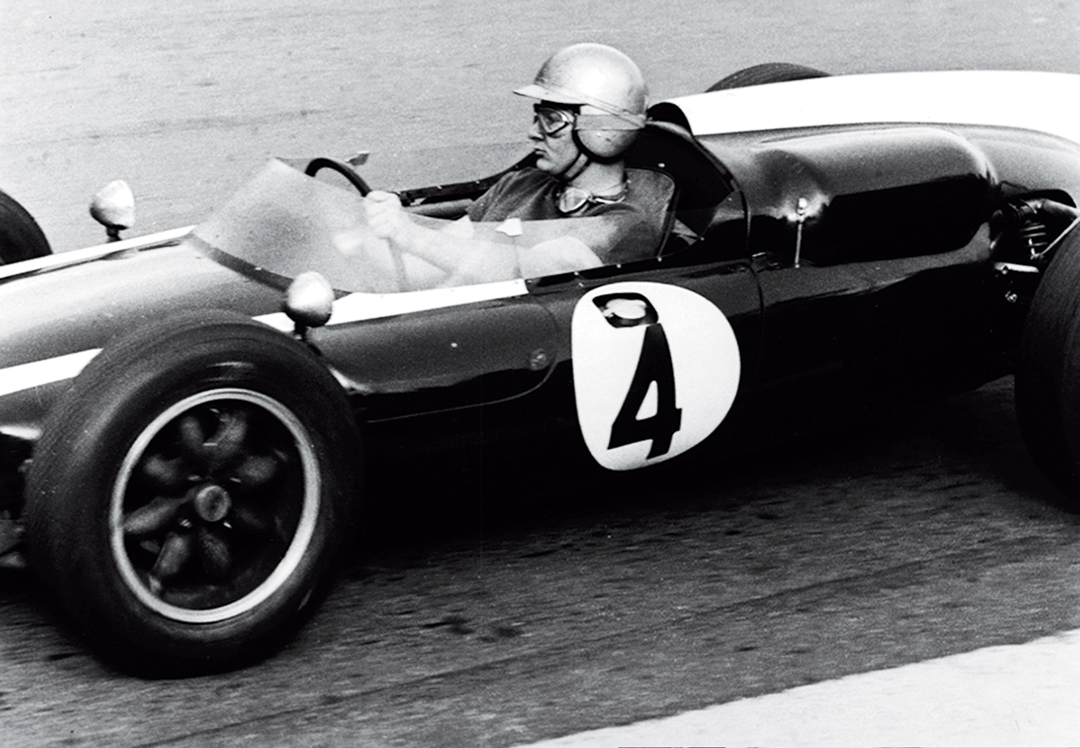

T-51…in Moss’s seat

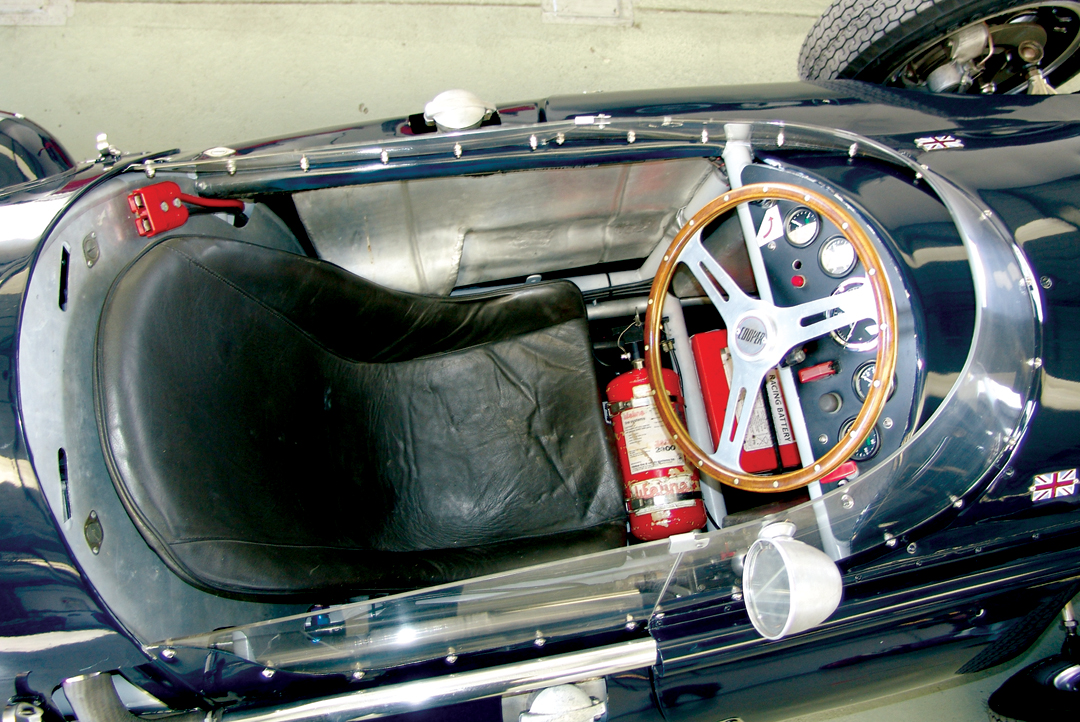

Behind the three-spoke wooden steering wheel sits a rev counter reading to 8,000 rpm, oil and temperature and pressure gauge to the right, and water and fuel gauges to the left. There’s a simple on-off switch on the left and starter button on the right. The gearshift looks complex but isn’t; it’s a straightforward 5-speed as per 1959. Despite a restoration some time ago, this car has lots of patina, with a leather seat and no seat belts, no roll-over bar, but a fire extinguisher under the driver’s knees. There’s a wraparound windscreen and only a mirror on the right-hand side…stay to the left! The interior has plenty of room to work in, and clearly the driver sits more upright than he will in the later “Lowline” model. The T-51 sits on Dunlop Racing tires, 5.00L15 on the front on alloy bolt-on wheels and 6.50L15 on the rear on wire wheels. The single exhaust exits out the right rear, and when you sit looking at the blue Cooper with its white noseband, you expect Rob Walker and Alf Francis to come sauntering around the corner any moment. As it was, the T-51 was sitting in the garage at Silverstone next to the Rob Walker Special, another Alf Francis project.

John Harper’s T-51 has the look and feel of an older car, but the performance was nothing short of amazing. I just loved that sensation of sitting upright, with no belts, and feeling the rush induced by slight roll-on entry to the corners, a barking from the back end as the power tried to bring the back end around. The circuit was a little quieter for my laps in the T-51, and the wind was blowing, which definitely caught me off guard on the straight once or twice. A little care had to be exercized in the shift from second to third, as the spring tended to want to push the lever back toward first. Once you know that, however, it is no longer a problem.

John Harper had some reservations about how effective the brakes were. What struck me, though, was that the car would whistle down the pit straight in fifth, use a dab of brake and flick down to fourth for the right-hand Copse and power through this quick corner. The T-51 was definitely a more basic car than its successor, with perhaps more weight at the back. That meant you had to drive with more attention on what was going on in the back, but it was also incredibly enjoyable. You could feel the front end bite as you turned in and went for the apex. I wouldn’t always get it right, but it was fun trying! I have to admit at least once seeing myself as Jack Brabham in 1959, hunched over the wheel and hauling the car through corners on the torque. It would bite, dig in and go. I just loved it! There is nothing quite like tigering up behind other cars and out handling them through the corners. This car could out maneuver much bigger and much newer racers.

T-53…Bruce and Jack were here

With the two Coopers sitting side by side, it is abundantly clear what John Cooper and Jack Brabham were thinking about as they made their way back from the Argentine GP early in 1960. They wanted something more compact, slimmer, lower, more streamlined. The T-53 is on Cooper wheels, with Dunlop Racing 6.50L-15 at the rear and 5.00-15 on the front. This car has a more “modern” appearance, equipped as it is with roll-over bar and harness. There are fuel fillers on both sides, a three-spoke leather-trimmed Cooper steering wheel, the chassis plate with FII-5-60 on the dash alongside the rev counter, this one reading to 10,000 rpm, though it is red-lined at 7,000. Gauges and switches are similar on both cars, as might be expected. The newer T-53 has a 5-speed gearbox, left and back for first and then the standard H-pattern. Again, the interior is comfortable, and the driver is slightly more reclined, though not yet horizontal as the Lotus 25 almost achieved two years later.

The gate had been removed from the gearshift on the car to make changing easier. Nevertheless, the box was very easy to manage, a good thing as the test session at Silverstone was very busy, with some quick cars, so there wasn’t a lot of time to go looking for gears! This car had both rear-view mirrors, which inspired a bit more confidence, but then again, they weren’t all that necessary as the car is very quick, and not many others were able to catch it. In fact, both Coopers had such impressive torque from the 2.5-liter Coventry-Climax, that they were quicker than anything else out of the corners and down Silverstone’s straights. A big Cobra came rumbling up behind the T-53 at the end of the straight into the complex, but was just left behind as the torque fired the nimble Cooper out of the tighter corners.

Using a 7,000-rpm limit, it was possible to grab fifth at two places on the circuit. It was down to fourth for Copse Corner at the end of the pit straight, holding fourth up to Maggotts and then quickly on the brakes for Becketts snatching third gear on entry. After a few laps, I relaxed enough to watch how good the traction was into and through this corner, which is important as you need to come out onto the straight quickly on the way down to the complex of left-right-right corners, through Woodcote and on past the pits. Historic racer and tester Willie Green raced both the T-51 and T-53, and felt the later car to be “100 per cent better in the handling stakes than the earlier T-51.” The T-53 seemed a “stiffer” car, more sophisticated, but I didn’t experience the rear end nervousness some drivers worry about. That was partly due to driving this car carefully but also because this car is superbly prepared. The road-holding was terrific, and that feeling of all the torque propelling you out of a bend and down the straight…well, it was unbeatable. The grunt of the Climax engine in both cars is just so surprising. It must have come as a great shock to the Ferrari drivers when the Coopers were staying with them at Reims. The car was very smooth and easy to drive, and the oversteer was not unnerving at all. It feels more refined than the T-51, and when you point it into a corner, the response is quicker. The power could stay on later and come on earlier, and the brakes made it all feel pretty safe.

The Dunlops gave lots of feel, and I found myself thinking what a good car this would be to learn to drive a rear-engine F1 car quickly. Driving toward the limit, however, is something different, and all Coopers get twitchy at a certain point. But if the Lotus, as Moss said, was twitchier…well, that needs some thinking about!

Specifications

T-51 / T-53

Engine: Coventry-Climax FPF

Cylinders: Inline-4

Bore and stroke: 94 x 88.8 mm.

Capacity: 2,462-cc / 2,495-cc

Compression ratio: 12 to 1

Power: 230 bhp / 245 bhp

Max torque: 204 lb.ft.@5,000-rpm

Transmission: 5-speed 3-plate clutch

Brakes: Girling discs / Girling discs

Front suspension: T-51: Wishbones and coil springs, anti-rollbar. T-53: Unequal double wishbone, coil springs, damper, anti-rollbar

Rear suspension: Wishbones and transverse, unequal double wishbone, coil leaf spring springs, damper, anti-rollbar

Chassis type: Tubular spaceframe / Tubular spaceframe

Wheelbase: 7’ 7” / 7’6”

Weight: 1,008 lbs. / 1,331 lbs

Resources

Thanks to John Harper and Barry Cannell for the loan of their cars, and their help, to Jarrah Venables, and to the Historic Grand Prix Car Association for letting us use their Silverstone test day.

Green, Willie.

Book of Racing Car Track Tests, 1989.

Sheldon, P. and D. Rabagliati.

A Record of Grand Prix and Voiturette Racing, Vol. 6, 1987.