1967 Lola T70 Spyder

The names Roger Penske and Mark Donohue are almost synonymous with the term Can-Am. While these two would totally dominate the Can-Am series in its later years with the mighty Porsche 917, they also played major roles in the championship’s first two seasons in 1966 and 1967. Using the fast and elegant Lola T70, Donohue and later teammate George Follmer would help put Penske Racing firmly on the racing map. With all the success that Penske Racing enjoyed during those first years (and in years to come), it was rather surprising to learn that the history of Penske’s Lola T70s had become a mixed-up conglomeration of fact, rumor and supposition. What seemed in the beginning like a very straightforward story on the Penske Lola T70, quickly turned into months of detective work to unravel the lineage of the half-a-dozen Lola T70s that were purported to have been run by Penske Racing in 1966 and 1967. With the gracious help of Sun Oil’s Penske liason Bill Preston, Penske driver George Follmer, the Penske restoration shops in Brookland, Michigan, and author John Starkey, we believe that we have finally unraveled the mystery surrounding the Penske Can-Am Lolas.

The Sun Rises

In 1966, Roger Penske made the serious decision to retire from driving and focus his attentions toward his business interests. The first stage of what would ultimately become an enormous business dynasty was turning his attention toward the burgeoning George McKean Chevrolet dealership that he had taken over in Pennsylvania. Fortuitously, an executive from the Sun Oil company, by the name of Elmer Bradley, purchased a new Corvette from Penske’s dealership that year and it wasn’t long thereafter that a deal was struck for Sun Oil, also know as Sunoco, to sponsor the racing Corvettes entered by the newly re-named Roger Penske Chevrolet.

After enjoying several early season successes at places like Daytona and Sebring, Penske hatched a plan to ratchet his and Sun Oil’s involvement up a notch by entering a Lola T70 in the newly announced Canadian-American Challenge Series (Can-Am). Not only would this effort add visibility and prestige to Roger Penske Chevrolet and Sun Oil, but the Can-Am also promised one of the richest purses in professional motorsport, an added advantage to the shrewd businessman/racer. With Sun Oil on board to fund a Lola T70 Spyder for Penske in the SCCA’s USRRC and inaugural Can-Am series, all Penske had to do now was find a suitable driver.

During this same period, a young driver by the name of Mark Donohue was beginning to make a name for himself in professional racing circles. After winning the SCCA’s E-production national championship in an Elva Courier and the Formula C national title in a Lotus 20B, Donohue caught the attention of Mecom racing driver Walt Hansgen who took Donohue on as a protégé. After sharing one of Mecom’s Ferraris, Hansgen brought Donohue along with him as co-driver when he joined the Ford GT40 effort in 1966. The pair finished 3rd at Daytona and 2nd at Sebring and travelled to the spring practice for Le Mans with high hopes of success. However, tragedy struck at Le Mans when Hansgen was killed after losing control of his Mk II GT40 in heavy rains.

Stricken by the loss of his mentor, Donohue returned to the States and was one of many racers at Hansgen’s funeral, where he happened to bump into Roger Penske. According to Donohue in his memoirs, “The Unfair Advantage,” Penske mentioned that he was looking for a driver for his Lola T70 in the upcoming USRRC and Can-Am championships and while he had been considering Dick Thompson, he was curious to know if Mark would be interested in driving on a race-by-race basis for $50/day. Seeing that the writing was likely now on the wall for his chances in the GT40 program, Donohue accepted and, in so doing, set in motion a chain of events that would lead to one of the most successful partnerships in racing history.

In the Beginning

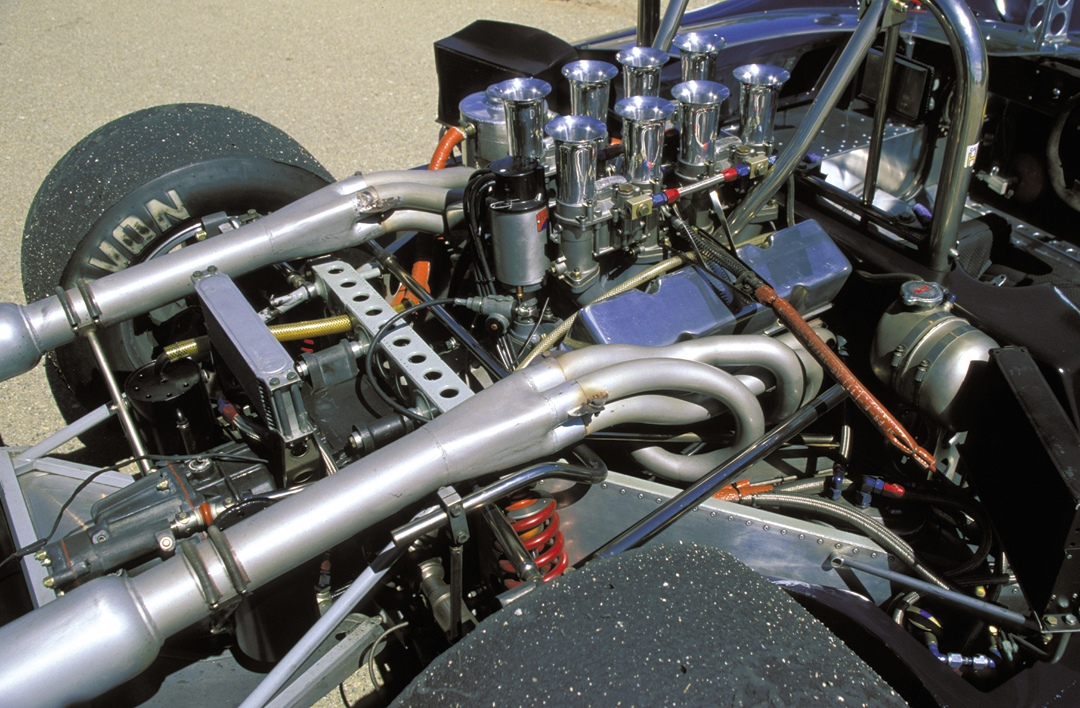

With funding from Sun, Penske purchased a new Lola T70 Mk II Spyder (#SL71/20) from John Mecom; and with the help of mechanic Karl Kainhofer and Sun Oil machinist Bill Scott, they set to work preparing the car for an upcoming FIA race at St. Jovite. In its conventional form, the 1600 lb. Mk II T70 featured an aluminum monocoque reinforced with steel bulkheads, independent front and rear suspension with cast magnesium uprights, coil-over shocks and anti-sway bars. The powertrains for these sports racers were usually a small block American V-8 driving power through a Hewland LG500 gearbox (in the later Mk III’s this would be upgraded to an LG600). However, in what would become typical Penske fashion, the team began to look for other engine options that would give them an “unfair advantage” against the opposition. Due to his tight connections with the engineers at Chevrolet, Penske opted to shoehorn the new 427-cu.in. big block V8 into the Lola, rather than the more conventional 333-cu.in. small block being used by the other teams. Unfortunately, oiling problems caused by poor drainage in the rocker covers destroyed the motor at the team’s maiden outing at St. Jovite and again at Toronto, prompting Donohue to remark after St. Jovite, “That was pure insanity…we never should have bothered. There were so many things wrong with that car that it was all I could do to just hang on.”

Photo: Casey Annis

So for the next race, a USRRC event at Watkins Glen on June 26, the team reverted to the more conventional 333-cu.in. small block. The change proved the right one as Donohue qualified 3rd and led for 20 laps until he crested a blind, right-hand turn and found a Porsche and another Lola parked sideways across the track. With nowhere to go, Donohue plowed into the Lola broadside with such force that it disintegrated the front end and forced open the gas filler cap, resulting in Donohue’s car immediately becoming engulfed in flames. As a result, Donohue suffered serious burns that required hospitalization and Penske’s first T70 SL71/20 was completely written off.

However, bolstered by the continued financial support of Sun Oil, Penske purchased another Mk II from Mecom, SL 71/35, and in just five weeks had the car – and a recovered Donohue – at Kent, Washington, for the July round of the USRRC. Finally, it all came good and Donohue went on to score his and Penske’s first win with the T70.

After a disappointing DNF at the next round at Mid-Ohio, Donohue and the Lola then took part in a Firestone tire test at Riverside Raceway on September 3, where they would also experiment with a new lightweight Airheart brake caliper. Unfortunately, one of the brake lines was installed too close to the hot disc and it failed at the 100 mph entry to Turn 7. Donohue shot off the track, through a series of haybales and plowed through the outer protective chain link fence. Clearly shaken, Donohue emerged from the wreck unhurt, but the same could not be said for the Lola which was later sold, as Donohue put it, “as a coffee table.”

Photo: Casey Annis

With little time left until the start of the inaugural Can-Am season at St. Jovite, Penske purchased his third Mk II T70 (SL 71/47) again from Mecom. Lady Luck would prove to be kinder to Penske and his third T70 during the 1966 Can-Am campaign. While Donohue did not finish the first round at St. Jovite, he did finish 5th at Bridgehampton, scored his first Can-Am victory at Mosport, a pair of 4th place finishes at Monterey and Riverside, as well as a 3rd place at the season-ending race at Las Vegas to finish 2nd in the championship behind John Surtees. Donohue capped off his roller-coaster first season with Roger Penske by driving SL 71/47 to victory at Nassau’s Speed Week in December, after which the car was sold to John Mayer.

Double Team

For 1967, Penske decided to field a two-car Can-Am team much to the dismay of Donohue, “It made it look like I wasn’t able to do the job against the Europeans…I didn’t like the idea of running on a two-car team.” However, Penske saw the financial advantages of twice as much sponsorship money and twice as much prize money, without too much of an increase in overhead. Penske initially planned to hire Chris Amon for the second team car; but when Amon backed out at the last minute, Penske gave the nod to George Follmer who had run some Trans-Am races for Penske the previous year.

Prior to the start of the 1967 USRRC season, Penske purchased a new Mk III spec T70 (SL 73/108) for Donohue. The combination proved unstoppable with Donohue winning six of seven races including Las Vegas, Riverside, Bridgehampton, Watkins Glen, Pacific Raceway and Elkhart Lake, while finishing 3rd at Laguna Seca. While this appeared to the outside world like an impressive tour de force, Donohue was more sanguine since the driving talent of the USRRC was not up to the same world-class caliber of the Can-Am. Donohue summed his feelings about the USRRC to Road & Track this way, “The USRRC was fine, but it was like playing tennis with your wife.”

With the USRRC championship sewn up, the Penske team now turned its attention to its two-car effort for the 1967 Can-Am season, which would kick off at Elkhart Lake in September. Donohue’s USRRC-winning car, SL 73/108, was turned over to Follmer for use in the Can-Am while a new Mk III, SL 175/124, was purchased for Donohue to race. According to Follmer, the plan was for Follmer to run the basic T70 without any modifications (presumably yielding a potentially slower, but more reliable car), while Donohue would test and race with all the development pieces that the team was working on at the time, including wings, side-draft carburetors and cold-air ram boxes.

In the first two races of the season, Donohue finished 2nd at Elkhart, with Follmer finishing 18th, while in the next round at Bridgehampton, Follmer finished 3rd and Donohue retired with a blown engine. With both drivers logging podium finishes in the first two races, the team moved on to the next round at Mosport, which proved to rekindle the team’s early bad luck in ’66.

During practice, Donohue had the left rear stub axle on his T70 fail going into the right-hand Moss corner. The car was badly stuffed into the embankment and upon later examination back in the pits was determined to have a severely bent tub. Just minutes later, Follmer had the tail section of his Lola come off as he crested the hump on Mosport’s back straight, which saw his car get airborne, careen off track and slice a telephone pole in half! The damage to his car was even more severe than Donohue’s. With valuable championship points and prize money at stake, the Penske team set to work repairing both cars for the next day’s race. As the team mechanics began the laborious process of trying to strip and straighten two tubs, Penske directed Sun Oil representative Bill Preston to take Penske’s personal plane and fly down to Indianapolis to get replacement parts. Preston recalls the adventure, “We flew down to Indianapolis in the middle of the night, went to George Bignotti’s shop and took the body pieces that we needed from one of the T70s he was working on…I think Parnelli Jones’ car. When we got back to the plane, we had to take all the seats out of the plane to fit the bodywork in and then flew back to Mosport so the team could fit the pieces in time for the race.” Not only did the weary Penske mechanics get both cars ready for the race, they even repainted the newly borrowed bodywork so that Follmer’s car would be presentable to Penske standards! As the “Captain” says, “Effort equals results.”

Photo: Bob Tronolone

In the race, Donohue retired with a blown engine, but Follmer finished a surprising 6th. This result was made all the more remarkable by the fact that his Lola was not only an inch shorter, but was uneven side to side. According to Follmer, “It made for a very interesting car to drive.” While Donohue’s SL 175/124 survived Mosport and went on to finish out the season, Follmer’s SL 73/108 was too badly damaged to continue. As a result, Penske purchased his 5th (and final) Lola T70, SL175/125, for Follmer to finish the season in, while SL 73/108 was cleaned up and used as a show car for the next couple of years by Sun Oil.

Photo: Bob Tronolone

With half of the ’67 Can-Am season completed, the series now moved on to California’s Laguna Seca where Follmer in his new Lola finished 3rd and Donohue retired with yet another blown engine. The subsequent event was the famed Los Angeles Times Grand Prix held at Riverside Raceway. Here, Donohue finished 3rd with Follmer finishing 6th, but by this time it was becoming increasingly clear that no one was going to be able to stop the McLarens of either Denny Hulme or Bruce McLaren from claiming the 1967 title.

The final round of the 1967 season was the Stardust Grand Prix, held in Las Vegas, Nevada. In the early stages of the race, it appeared that it would be yet another round of the Bruce & Denny show, with McLaren and Hulme out in front. However, both suffered uncharacteristic engine failures that when combined with problems for Jim Hall and Dan Gurney, handed the lead to Donohue. Donohue looked set to win his first and only Can-Am victory of the season when on the last turn of the last lap, his Lola began to sputter – he was running out of fuel! Donohue limped across the finish line, but not before Surtees pipped him for the lead and the win. Follmer ended his race and season with a retirement suffered at the hands of a broken shifter fork.

Photo: Bob Tronolone

In the final tally, Bruce McLaren had won the championship with Donohue finishing 4th and Follmer tying Mike Spence for 6th. Looking forward to the next season, Penske could see that the sun was setting on the venerable Lola T70 and was rising on the new McLaren M6. Penske thus made the decision to run McLarens in 1968 and so sold his two remaining Lolas at the end of the season, thus closing an important chapter in both Can-Am and Penske racing history.

Driving a Penske T70

The last of Penske’s Lola T70s (Follmer’s SL 175/125) continued racing after the 1967 season. At the end of the season the car was sold to Jerry Hansen who entered it in the SCCA’s All-American Race of Champions (the ’60s equivalent of today’s SCCA Run-Offs®) where he won the C-modified class with it. From there the car’s history gets murky until it is bought in the ’80s by Chuck Haines, who in turn sells it to Jim Campbell, who completely restores the car to its original Penske configuration. By the late ’80s, SL 175/125 is then sold to John Casado who in turn sells it to Tomy Drissi, who finally sells the car to its current owner, Steve Young.

Young was gracious enough to allow VRJ an entire test day at Southern California’s Willow Springs Raceway with the car, as a way of getting to properly come to grips with this important piece of Can-Am history. Needless to say, I didn’t have to be asked twice!

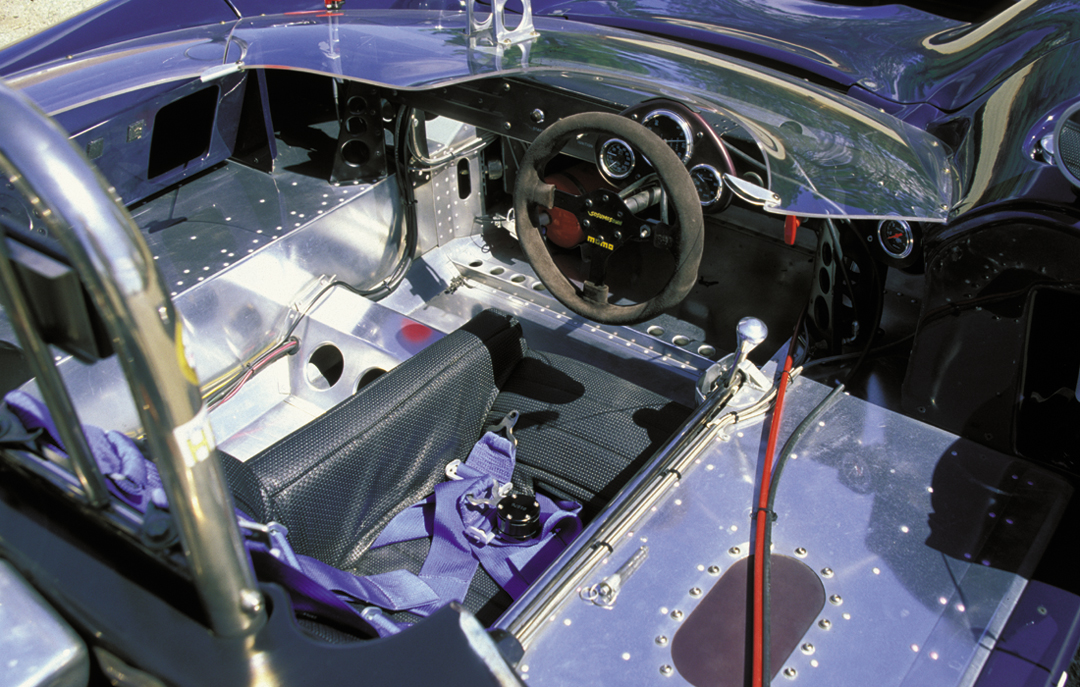

As I sit on the ground about 20 feet away from the Lola glistening in the hot August sun, I’m struck by the fact that this is not only one of the most sexy shapes to ever grace a racecar, but it is also perhaps the most animal-like. The curvaceous haunches of the T70 give it a very different quality than other racecars – the car almost seems catlike. Stepping over the plexiglass, wraparound windscreen, I stand in the right-hand driver seat and slide myself down into the cockpit. You don’t sit so much in the Lola as you are swallowed by it. Peering out through the front windscreen, as I buckle up the safety harness, my field of vision is dominated by two enormous blue fenders either side of the car. You sit so low in the T70 that the tops of the fenders are nearly above your head, yielding the sensation of sitting in a giant blue valley.

Once buckled in, Young plugs in the battery, I turn on the ignition, flip on the fuel pumps, press the accelerator pedal a quarter of the way to the floor, swallow the enormous lump in my throat and press the starter button. With several whirring grinds from the starter motor, the 333-cu.in. small block Chevy blares to life and immediately assumes a lumpy throttle. Pressing hard on the stiff clutch pedal, I pull back and toward me to select what I hope will be first gear in the Hewland LG600 gearbox, raise the idle to about 1500 rpm and gingerly let the clutch out. To my pleasant amazement, the T70 pulls away from the line and I’m spared the embarrassment of stalling this magnificent car!

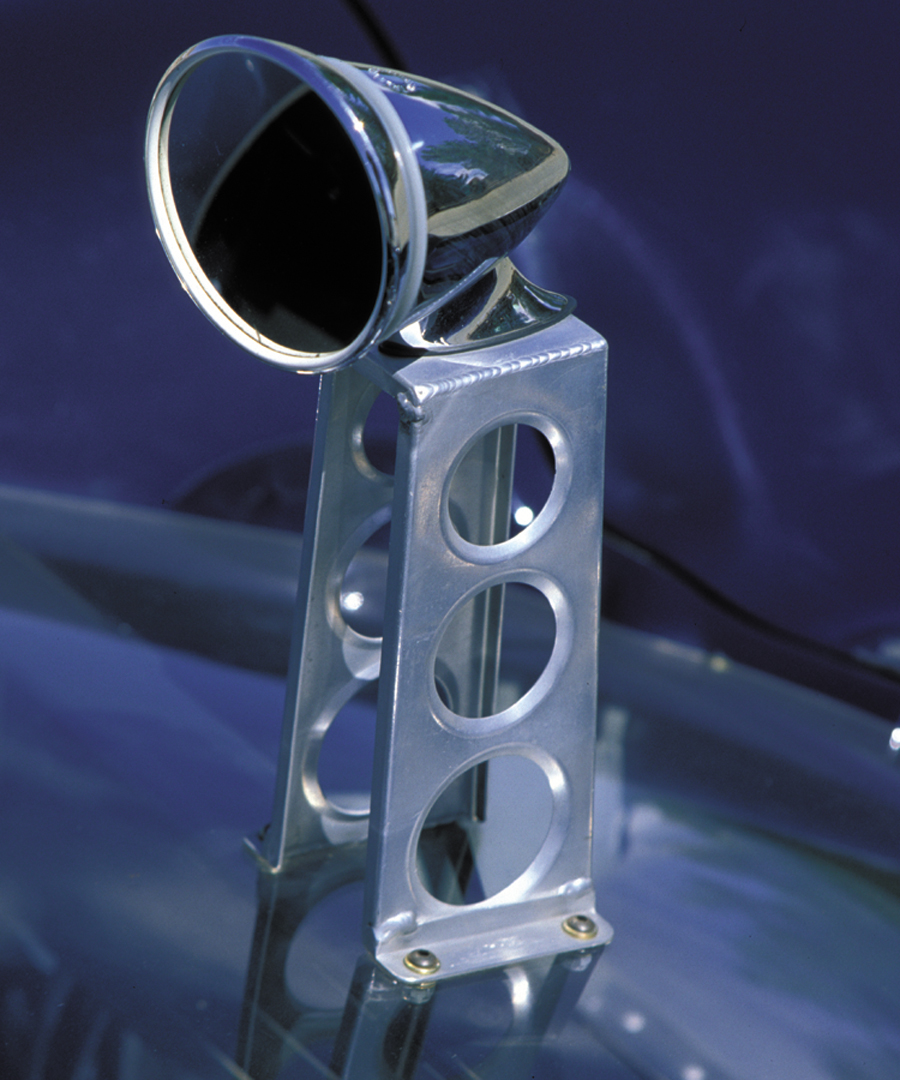

With the hard part over, I accelerate out onto a nearly empty track and begin to take my bearings. Visibility forward and to the sides is good, though those enormous sexy front fenders do severely impede your vision of the apex at turn-in. Out the back, visibility is about average – meaning that you sincerely hope that no one is lurking around back there because the three small, vibrating Raydot mirrors mean you’ll likely feel them before you see them!

After a lap or so to make sure that everything is properly warmed up, I start to stand on the gas exiting Willow’s decreasing radius Turn 9 and accelerate hard down the front straight. The small block Chevy pulls like a freight train – from third, I run the Chevy up to about 7000 rpm and snatch 4th and quickly thereafter pull fifth and continue to accelerate down Willow’s long front straight. By two-thirds of the way down the straight, I have the unpleasant experience of having the wind attempt to rip my helmet off my head. As a result, I tuck in my chin; knowing that I’m now entering a realm of scary fast speed.

At the end of the straight, I lift off the gas, stand on the brake, blip the throttle and engage 4th gear. The experience is so smooth and satisfying, I make another downshift to 3rd, release the brake, turn into Turn 1 and progressively squeeze on the power. The T70 drifts through the turn so sweetly, a tear comes to my eye (OK, maybe it’s the wind in my contacts, but it is one of the most satisfying feelings I’ve enjoyed behind the wheel). Accelerating toward Turn 2, I lift into the entrance to set the car up, start my turn and very gradually squeeze the throttle on as I power around the long right-hand turn. As I exit onto the short chute between 2 and 3, I briefly shift up to 4th, and just as quickly brake hard and down shift two gears for the sharp Turn 3 left-hander that launches you uphill to the Budweiser Balcony. As I accelerate up the hill and around the top at Turn 4, I’m impressed with how driveable the T70 is – solid, stable handling with controllable oversteer beckoning at your right foot.

Next I rocket down the hill toward Turn 5 and then back uphill over the blind right-hand crest at Turn 6. If a car has any evil handling characteristics, you’ll find them at the crest of Turn 6 with tragic consequences. Fortunately for me, the Lola is predictable and rock stable as I crest the hill and snatch 4th gear, accelerating down the long back straight toward one of the hairyest corners in the Western United States. Turn 8 is all psychology – in theory, it is supposed to be able to be taken flat, but not today and not in Steve’s valuable piece of Can-Am history! With a small confidence lift prior to 8, I carry what still seems like an impressive amount of speed into the right-hander and immediately set myself up at the outside of the track for the tricky decreasing radius Turn 9 again. Waiting until the last moment before I seemingly fall off the face of the planet, I start my turn-in, stand on the gas and feel my eyeballs flatten as I rocket out onto the front straight again for another round of helmet-ripping bliss. If this car has a shortcoming, I can’t find it.

Buying a Penske T70

As mentioned above, Roger Penske raced a total of five Lola T70s and at least two of those were completely destroyed. That only leaves three original examples, which certainly limits one’s options. In general a total of 15 Mk I’s, 33 Mk II’s and 19 MK III’s were built. Prices for a standard Lola T70 can start around $175,000 and go up from there depending on history. In the case of the Penske cars, history definitely commands a premium with these cars, potentially hovering around the $300,000 range – assuming that one of the owners could be tempted to part with it.

Specifications

Examples Built: 19 examples (Mk III)

Track: Front: 58.3”. Rear: 60”

Wheelbase: 95”

Overall Length: 157”

Overall Width: 74”

Height : 33.5”

Weight: 1500 lbs. (Mk III)

Chassis: Monocoque using steel and aluminium

Suspension: Front: Independent, with coil springs, magnesium uprights, anti-roll bar and telescopic dampers. Rear: Inverted wishbones at bottom w/ single upper link, radius rods, magnesium uprights and anti-roll bar

Brakes: Vented discs (12”) with four-piston alloy calipers (Mk III)

Engine: Traco-built Chevrolet 364-cu.in. small block (4.0” x 3.625”) with either four downdraft or sidedraft Weber carburetors

Horsepower: 495 bhp @ 6500 rpm, 490 ft-lbs @ 4500 rpm

Gearbox: Hewland LG500 (Mk I) , Hewland LG600 (Mk II, III)

Bodywork: Fiberglass

Wheels: Front 15” x 8”, Rear 15” x 10”

Resources

Lyons, Pete

Can-Am

Motorbooks International, 1995

ISBN 0-7603-0017-8

Starkey, John

Lola T70

Veloce Publishing, 1997

ISBN 1-874105-89-8

Donohue, M. & Van Valkenburgh, P.

The Unfair Advantage

SAE Publishing, 2002

The World of Sports Prototype Racing

www.wspr-racing.com

Special thanks to Steve Young, George Follmer, Bill Preston, Pete Luongo, and John Starkey for their help and patience in unraveling the tangled history of the Penske Lolas, once and for all.