1935 Sulman Singer

We all have defining moments in our lives that remain with us. Moments that leave an indelible mark on our memories, maybe even our psyche. Memories so defining, they actually change the way we look at things.

There are a couple of events in my life that defined my interest in historic motor sport. No, I didn’t witness the flailing arms of a Gonzales, the smooth style of a Fangio or perhaps the power slides of a Moss. Nothing so spectacular. Growing up in Sydney, Australia, we hardly ever got to see the likes of such greats except for the Tasman period, but that’s another story.

My first defining moment was back at Easter 1970, when a friend and I traveled to Mount Panorama, Bathurst, some 130 miles west of Sydney. From 1939 through to 1973, motor sport enthusiasts made a bee line for Bathurst to soak up the aromas of Castrol R at the annual Easter race meeting. Sadly, just after the 1973 meeting, the decision was made that it was no longer economically viable and, from then on, the only time when the mountain circuit reverberated to the sound of racing engines was the annual Bathurst 1000 sedan races.

First Visit

I was just 19 and just loved motor racing and made my first visit to Bathurst. We had camped out at the top of the mountain where it was possible to watch the cars fly across the top before hurtling themselves off at Skyline, through the Dipper and down the esses. Far more interesting than watching them drive by in a straight line along one of the straights. However, through the trees and the haze, we could make out parts of Conrod Straight and the notorious humps—slight rises in the road that caused the front of some cars to lift, especially if there was a cross wind.

I recall vividly a sports racing car event with the likes of Sprites right through to V-8 Can-Am-style cars. In particular, I was taken by the style of car No, 99 and the driver’s smooth line. At that time, I didn’t realize that it was a 1,220-cc Climax-powered Lotus XI being driven by Tom Sulman, a very well known name in Australian motor sport.

The Mount Panorama circuit is 3.84 miles long, so at racing speeds there was just under 3 minutes between each time we saw the cars. I had taken a liking to car No. 99 and was looking forward to seeing it again, but while the other cars went passed, there was no sign of the Lotus. Suddenly there was an eerie silence, almost deafening. You know what it’s like when you’re surrounded by noise that suddenly stops—the lack of noise is more profound than the noise itself.

Soon, the low level noise of conversations started to rise. However, way off in the distance, we could see commotion along Conrod Straight. Back then, communication wasn’t the best, but soon the word had got around that as Tom Sulman’s Lotus XI had approached one of the humps, it veered across the track, hit another car followed by the earthen bank before cartwheeling a further 100 yards. Sulman lost his life and Australian motor sport had lost one of its most endearing personalities. And while back then I didn’t quite understand the significance of it, we were all deeply saddened.

First Sighting

Skip forward a few years and we were at Amaroo Park, a tight circuit built into a natural bowl to the northwest of Sydney—an enjoyable circuit for competitors and spectators. Amaroo Park is sadly no more, having succumbed to the inevitable onslaught of suburbia.

The meeting wasn’t special, just one of the periodic open events staged by the Australian Racing Drivers Club. I can’t recall what was racing except for just one car. It was in a race for open-wheelers. Probably a grouping of Formula Juniors, F3s and the like. However, there was also a small number of Formula Libre cars best described as “Formula Anything Goes.” Toward the end of the field was one particular car. Red in color with what was perhaps the shortest wheelbase of anything I had ever seen. The driver certainly wasn’t in his youthful prime but clearly from the smile on his face he was enjoying himself. Plus apart from his customary driving suit, gloves and helmet, he was sporting a bushy silver mustache and wearing a scarf that trailed behind him. At race’s end, I stood clapping my hands above my head and received a cheery wave in return.

I was enthralled and needed to know why this car, clearly from another era, was out there and why its driver was having so much fun. It was my first introduction to the Sulman Singer and to Ron Reid its owner. Significantly, it was also my first introduction to historic racing cars and, while Australian enthusiasts had witnessed some races for historic cars at open events, it wasn’t until January 1976 that the first all-historic race meeting was held—also at Amaroo Park.

I attended historic meetings regularly thereafter and, yes, the Sulman Singer along with Ron Reid complete with mustache, smile and flowing scarf were always there. It was to be a couple of years before I plucked up the courage to introduce myself to Ron, but I finally did and reminded him of the earlier meeting. He said he ran at those meetings for the fun of it.

To many enthusiasts, the Sulman Singer is historic racing in Australia. If you attended any meeting over the last 30 years, it would be a rare event indeed not to see it in the pits and out on the circuit. Sadly, Ron Reid’s scarf stopped blowing in the wind in 1999, but the Sulman Singer is still very much with us and looks to be so for the next 70 or so years.

Tom Sulman

Any story concerning this cornerstone of Australian historic motor sport cannot be told without looking at the man who originally built the car back in 1935.

Born in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, in the dying days of the 19th century, Tommy Sulman at just 10 showed signs of his automotive future by building a billycart to race through the orchard behind the home. He later rescued an FN motorcycle from the scrapheap and rebuilt it, the first of many motorcycles that were to influence his life. With an architect father it’s not surprising that Sulman was a skilled artist and cartoonist. So skilled that he sold his cartoons to a number of Sydney’s newspapers of the time, with the income going to motorcycles.

Photo: Steve Oom

With the Great War raging in Europe, Tom Sulman left school at 17 to enlist. However, his father had other ideas sending him north to cattle country in Queensland. His new Harley-Davidson was small consolation. At 18, Tom no longer needed his father’s permission to enlist, so he returned to Sydney. Sadly, one of Tom’s brothers, a pilot instructor, was killed in France while training a new pilot.

On leaving the forces, Sulman took advantage of the government’s repatriation scheme by studying engineering at a technical college. His natural talent was apparent when he turned his mind to the design of many motor vehicles, including that of a basic vehicle built around an Excelsior engine called the Sulman Simplex. While rudimentary, it would best be described as a cyclecar, a style of vehicle that was gaining in popularity. It was so well received that a further five were built with Lake, air-cooled V-twins. With financial backing, it looked as if Tom Sulman at 21 was destined to be a motor vehicle manufacturer. In far-off England, William Morris had other ideas and released the Austin 7—a small car in miniature—in response to the cyclecar trend. Virtually overnight, cyclecars were practically eliminated from the road, and Tom Sulman’s manufacturing future now looked grim.

Two-Wheel Racing

It’s hardly surprising that Sulman’s first venture into competition was on motorcycles, making his name on Harley-Davidson, A.C.E. and Henderson machines. Now working in vehicle sales he naturally progressed to competing with 4 wheels, especially behind the wheel of various Citroens and Austins in the popular trials of the time.

While Tom Sulman was making a name for himself, entrepreneurs realized that there was money to be made from motor racing. To capitalize on this, a large concrete-bowl speedway was constructed in the southern beach area of Maroubra. The organizers were keen on persuading Tom to compete and offered to buy him a front-wheel-drive Miller. Then fate stepped in when he married at 26, promising his bride that he wouldn’t race for a year. It was probably a decision that saved his life, as Maroubra Speedway became notorious when cars and drivers found themselves propelled over the bowl’s steep concrete edges.

As soon as the year past, Tom built himself a racing Salmson that he ran through to 1930. At the same time, he separated from his wife and the world’s economy spiraled into the red. Customers cancelled their new car orders and the company Tom was with went into voluntary liquidation.

England-Bound

Something had to give, and the Salmson was sold off with Tom buying a one-way ticket for England, arriving there with just £15 to his name.

Tom was prepared to do anything to make ends meet from spruiking, selling door-to-door, to driving a touring coach. Eventually, he purchased a cheap set of tools and started working on cars in the owners’ backyards before starting a repair business. He purchased a three-wheel Morgan, which sparked the idea in his head to start an American-style speedway in the UK. The Morgan was duly modified with an additional wheel, Ford steering and a Coventry Eagle engine.

Tom’s first race meeting in the UK at Crystal Palace was a success leading to further meetings and a total of 10 similar cars being built.

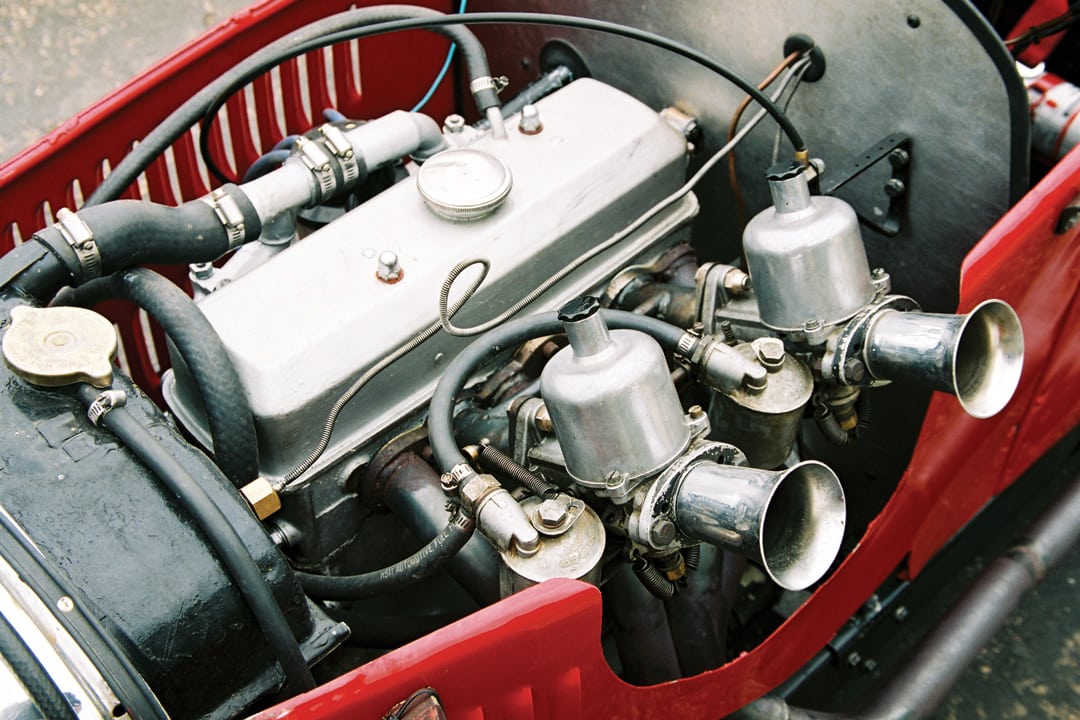

Speedway grew quickly in popularity, and in 1935 Tom was approached by the local Singer dealer, Bill Kydd to build a car around a Singer Le Mans engine and radiator. Tom built the car starting with a fabricated C-section chassis, G.N. chain-drive gearbox and solid rear axle, with Salmson steering and brakes.

The car was run successfully at Dancer’s End Hillclimb but Mr. Kydd’s plans didn’t quite work out as his books went into the red and Tom was left with the car and not the money he was hoping for. The Singer was put up for sale in The Autocar on May 29, 1936, for £210 but thankfully for us it didn’t sell. Tom also advertised replicas without success. However, there is some thought that a second car was built but after 70 years it’s difficult to substantiate.

As fate would have it, Tom Sulman kept the Singer-powered car and, in an interview given to Australian Autosportsman in 1969, said that he ran the car at Shelsley Walsh and Prescott, with a works supercharged 750 Austin being the only car that beat him at the latter.

Speedway success was short lived, especially when the four-wheel-drive Skirrows were released. Unable to best them with the Singer, he joined them with his own four-wheel-drive car. A small accident was soon followed by another in 1938, as he was pushed into a timber perimeter fence, not only severely damaging the car but braking a collarbone, ribs, damaged spine and a concussion. More dramatically, he received a broken nose and severe facial lacerations requiring plastic surgery, leaving him with a permanent “face-lift” appearance.

Photo: Steve Oom

Amazingly, a sympathetic speedway enthusiast started the “Sulman Fund” to receive donations from fellow fans. In thanks, Tom Sulman donated a silver cup to be called “The Tommy Sulman Challenge Trophy.”

All this fun came to a stop when a bloke in Germany set his sights on Poland and the world was again at war. Tom joined the Royal Army Service Corps, initially instructing motorcycle riding and later seeing active service in Africa and Italy. He was later discharged a captain.

Australian Singer

After the war Tom decided to return to Australia but being in the British army meant that he had to find his own way. Scheduled air services were still some time off, so he signed on as engineer on a surplus Halifax bomber that had been converted to take 18 passengers. Tom knew absolutely nothing about aircraft, the pilot had never flown a loaded Halifax, the copilot was a young woman who had never flown anything bigger than a twin-engine plane and the radio had a 10-mile range. Miraculously they made it!

Back in Australia, Sulman immediately went back into the motor vehicle repair business. The Sulman Singer? It was still in England but was brought out to Australia by steamer in 1947, without a body as not only was it cheaper to ship but government import duty on a complete car was greater.

With a new body, the car and Tom were ready for action. This was in June 1947, at a race meeting around the airfield at Nowra, south of Sydney where he narrowly won the under-1,100-cc scratch race. Later in October, Tom lined up for the first postwar Australian Grand Prix at the reopened Mount Panorama circuit. It was a handicap event over 38 laps or 150 miles, with the slowest car, an MG J2 driven by Les Burrows starting 37 minutes before the quickest car, Alf Barrett’s Alfa Romeo SC. With the Sulman Singer’s 947-cc, it was given 28 minutes start. Other cars in the field included Lex Davison’s 7.6-liter Mercedes, Hope Bartlett’s Brooklands Dixon Riley and the MG TC of Elliott Forbes-Robinson who, along with his son, made names for themselves later in American auto racing.

After a race time of 2 hrs 39:46 mins, first across the line was Bill Murray’s well-tuned MG TC with the Mercury V-8 Special of Dick Bland 2nd. Tom Sulman came in a highly credible 5th in 2 hrs 41:48 mins.

Just 3 months later, the 1948 AGP was held at the Point Cook Royal Australian Air Force base in Victoria. It was a stiflingly hot day and Sulman lasted just 17 of the 42-lap race, when the Singer engine expired. Undeterred, Tom fronted up at Bathurst over Easter, winning the under-1,100-cc event. Similar successes followed at the long-defunct Mouth Druitt circuit and in hillclimbs and sprints in and around Sydney. During this time, Tom had changed the troublesome chain-drive arrangement first a Singer gearbox and finally to an MG TC box along with a modified Ford Model A rear axle.

Moving On

It was 1950 and, at 50 years of age, Tom Sulman urged for more speed, especially at Bathurst where the Singer’s sub-100- mph top speed was a hindrance. It was sold off and replaced by an older 4C Maserati capable of 125 mph. With the Maserati, he was a winner and scored successes in both Australia and New Zealand. At one meeting at Orange, west of Sydney, Tom Sulman won five races in a single day.

In 1955, Tom together with fellow Australians Les Cosh and Tony Gaze traveled to England, bought three Aston Martin DB3Ss and formed the “Kangaroo Stable.” Teaming with them was also David McKay and a bloke by the name of Jack Brabham. In that year, they had 15 European races lined up, but the Le Mans tragedy put a stop to many meetings.

Tom returned to Australia with the DB3S but it was sold in 1958 and replaced by the first of two Lotuses. For a time, Sulman maintained a private team of the two along with an Australian-built Lynx. In the 1969 interview, he was effusive about obtaining a 1,500 crank for the Lotus XI and at 68 had retained his racing license. Sadly, Australian enthusiasts would only see Tom Sulman out on the circuits for another year.

Yellow Singer

The Sulman Singer passed hand to hand, and while featuring some successes never quite gained its former notoriety. From 1950 to 1965, there were six different owners,while it had received an unusual streamlined nose cowling and a coat of yellow paint.

Ron Reid wasn’t looking for old racing cars during a periodic visit to Sydney in 1965, but he was about to make a life-changing decision. Ron ran a garage in the country town of Murrumburrah, southwest of Sydney. Normally, during his visits, he would scour the auction yards looking for suitable automotive stock to sell. Somewhat disgruntled that he couldn’t find anything suitable, he came across a forlorn-looking, old racing car in a Sydney auction yard. A raise of the hand and $400.00 later, he was on his way home with the Sulman Singer.

No stranger to the old racing car scene, as soon as he arrived home, Ron phoned another doyen of Australian motor sport, Jon Cummins. The conversation between these two slightly larger-than-life characters must have been lively as Ron let on that he had bought the car feeling sorry for it. Surprisingly, he asked Cummo what he should do. Anyone who knows Cummo wouldn’t have been surprised with the answer. “Race it of course!”

Historic racing was still a decade away, and the Sulman Singer was really just an old racing car. Ron’s son Mal remembers the first competition event quite clearly, except it’s more remembered for the car falling off the trailer along the way! Ron then set about to rebuild it while removing the unsightly nose and fitting its now-familiar modified Austin 7 radiator. The less than mellow yellow was also changed to the familiar red.

In the hands of Ron Reid, the Sulman Singer was alive again and the Ron Reid trailer along with his smiling face, silver mustache and scarf became a familiar sight at circuits all over the southeast of Australia.

Next Generation

Like their father, both Mal and David Reid are deeply involved in historic motor sport and unsurprisingly both have strong memories of Ron and the car. Mal is the oldest and he looks back at helping his father with the car, and then Ron strapping a set of trade plates onto the roll bar to test it around the country roads, shouting out as he drove off, “If I’m not back in half and hour, come and get me.” It didn’t matter that Mal had yet to reach driving age and didn’t have a license. In David’s consciousness, the Sulman Singer is a permanent feature, as he can’t remember a time in his life when the little car wasn’t around.

Mal recalls that after his father rebuilt the car, he entered it in what was called Division 3 racing, perhaps the last outpost for the endeared Australian special.

“There wasn’t really a class for the car,” Mal told us. “However, Dad kept entering and running at circuits like Hume Weir, Oran Park and Catalina. Every six weeks the whole family would be packing the trailer heading off for a weekend of racing. Back then there was the occasional race for historic cars at larger race meetings. I remember one AGP meeting where there were thousands of people there to watch the F5000s, the popular touring cars and Dad out with the historics. It was great fun.

“Going to Bathurst during the ’60s with all of us was especially popular, as we used to camp out in the pits.”

David Reid recalls the meetings at Bathurst with the same fondness. “We had one of those pop-up tents that we would pitch and sleep in right there. During the day, when Dad was tinkering with the car, we would team up with other kids and disappear into the creeks around Mount Panorama looking for yabbies (Australian freshwater crayfish.) When historic meetings started at Amaroo Park during the mid-1970s, we always returned early from our holidays and then repacked for the races. Dad used to love his car racing and then sitting down at the pub on the way home to have a drink with his mates.”

It’s fitting that the Sulman Singer is remembered along with the names of Tom Sulman and Ron Reid. For Tom gave the car life way back in the 1930s and Ron brought it back to life 30 years later and, for the next 35 years, endeared its way into the hearts of so many Australian motor sport enthusiasts.

It’s also fitting to recount a little story that happened at a race meeting at Winton Raceway in Victoria. Australian motor sport generally comes under the watchful eye of the Confederation of Australian Motorsport. At Winton, a zealous CAMS official spied Ron Reid enjoying himself out on the circuit with scarf in full flight. No doubt with scenes of Isadora Duncan in his mind, he black-flagged Ron and the Sulman Singer. Ron by that stage had very much become the figure of historic racing, and there was a great hue and cry from enthusiasts. It was just before Ron’s seventieth birthday and, for a very much tongue-in-cheek gift, he was presented with two new scarves of the finest silk. However, stitched to each scarf was a label with the words “CAMS Approved.”

Both Mal and David Reid recall that after it was restored, they took the Sulman Singer to the 2004 Phillip Island races and were thrilled by people saying how great it looked and how proud their father would have been.

Australian historic racing was greatly saddened with Ron’s passing in 1999. As he requested, he was buried in his racing suit while the much-loved scarf remains a centerpiece of a collage of photos and memorabilia shared within the family.

Caring for the Sulman Singer

Photo: Reid Family Collection

You’ll have no chance in the world of having a Sulman Singer in your garage. It’s been in the Reid family since 1965 and both Mal and David are adamant that they also will be driving the car well into their seventies.

We had a chat with Michael Vigneron who operates Highlands Race & Classic specializing in historic racing vehicles. After Ron’s passing, Michael was entrusted with the Sulman Singer’s restoration. “When I first got it into my shop, it wasn’t too good,” Michael said. “That was about four years ago. After stripping it down, I went right through everything looking for what needed doing. The chassis was severely cracked and the body very sad.

“The body and engine were sent for repair, coming back in excellent condition with the engine probably seeing close to 60 bhp. Throughout the car’s later life, it suffered from bearing problems, so a modified Mercedes oil pump was fitted to improve oil circulation. However, the long-suffering crankshaft cried “enough!” Luckily, we managed to find a complete Singer Le Mans engine for just $120.00 and put together one using pieces from each. I also modified the sump and that, along with the pump, solved the problem. Currently, the engine is far less modified making it very easy to drive, and it should stay in top shape for some time.

“Except for the suspension, everything is bolted direct to the chassis,” Michael added. “It’s quite solid but I suggested fitting a roll bar extending to the tail of the chassis. I could see what would happen during a rear shunt with the Armco. This also strengthened the car even further.

“I usually see the car before every major meeting and give a quick check going over each nut and bolt ensuring everything is correctly tightened. Of course the oil is changed, brakes are checked and I adjust the toe-in where necessary. It really is a simple little motor car that is a delight to drive.”

Driving the Sulman Singer

Photo: Autopics.com.au

As I got into the Sulman Singer, the first thing that struck me was that almost half the steering wheel was missing! It soon became bleeding obvious when I tried to move away. With the gearshift between my splayed legs, I wouldn’t have had a chance of changing gears by reaching through the wheel.

The pedals? Well, they were interesting. Not quite like a central accelerator, but the clutch felt quite comfortable under my left foot and the accelerator likewise under my right but the brake was directly above and slightly to the left. Needless to say that, after 30-plus years of racing that one car, you would become used to it.

I started off around the Wakefield Park circuit with my memory going back to seeing Ron Reid looking so stylish and comfortable in the car. Michael Vigneron had told me to keep an eye on the temperature gauge and, if it looked as if the engine was getting hot, then press the button marked “A,” which turned on an electric fan. So I had one eye on the gauge, one on the rev counter and one on the road ahead.

It didn’t look like an MG box, which was true, as later Michael told me that it once again has a Singer four-speed. First, second and third by the end of the straight. Hard on the brakes and, surprisingly, it does slow down—thank heavens for the power of four-wheel drums. Then there is a run up the slight hill with the car held in third, while lining up for the right-hander that quickly turns 90 degrees. Then back through to second for the corner and down the hill in third and top toward the tricky left-hander that is taken in second, hopefully with some élan—at least it sounds good. Back to third and what seems like a continual right bend across the back of the circuit. I select top for a nanosecond, but it’s time for the opposite cambered hard right turn onto the straight. It’s soon into top and I’m watching the tach and keeping the revs below four grand. There is something special about open wheelers and watching the wheels jump around with the bumps!

The Sulman Singer is just a delight to drive. With its long stroke engine thumping away in front, adept gearshifts and brakes that proved to be progressive and assuring, I felt as if I could have put in some useful times. With its short wheelbase and smallish engine, I certainly didn’t attempt any power slides, but the car felt lively through my hands and behind. If “chuckability” was a word, it would be perfect to describe how I felt about the Sulman Singer.

To write about the Sulman Singer has been a delight. To experience a car that has become known as one of the mainstays of Historic Racing in Australia is a real privilege.

Chassis: Fabricated from C-section steel.

Body: Alloy single seater.

Wheelbase: 6ft 7in

Weight: 1,093 lbs.

Suspension: Front: Salmson beam axle, quarter elliptic springs and lever arm hydraulic shock absorbers. Rear: Modified Ford Model A live axle, quarter elliptic springs and tubular hydraulic shock absorbers.

Steering Gear: Salmson worm and peg.

Engine: Four-cylinder, 1,261 cc (64.75mm x 95.00mm)

Power: 50 bhp at 6,000 rpm

Carburetor: Twin SU H4 carburetors.

Ignition: Scintilla Vertex magneto.

Clutch: Single dry plate.

Gearbox: Modified Singer gearbox.

Gears: 4 forward, 1 reverse.

Foot Brake: 4-wheel Salmson Perrot drums.

Hand Brake: Nil

Wheels: Wire wheels with Salmson hubs.

Tyres: 3 X 15 Michelin.

Resources

John B. Blanden, Historic Racing Cars in Australia, 1979 & 2004, Turton & Armstrong Proprietary Ltd Publishers. ISBN 0 908031 83 1.

Graham Howard, Stewart Wilson, John Blanden, The Official 50-Race History of the Australian Grand Prix, 1986, R&T Publishing. ISBN 0 9588464 0 5.

John Medley, Bathurst—Cradle of Australian Motor Racing, 1997, Turton & Armstrong Proprietary Ltd Publishers. ISBN 0 908031 70 X.