The late 19th century was not a great time for the Farina family to be bringing up eleven children in rural Italy. The tenth was christened Battista, and with all these mouths to feed the Farina family upped sticks and headed away from their hometown area of Cortanze d’Asti to the city of Torino for the simple practical reason that there might be more work there. Battista had been nicknamed Pinin, which, in Piedmontese dialect meant the smallest or baby of the family. The name stuck.

Meanwhile, the search for work had led an elder brother, Giovanni, to be appointed to one of the hundreds of carrozzerie in Torino, Marcello Alessio. Pinin would often go and meet his brother after work, and fell in love with cars in the process.

In his spare time—he already had a job cleaning all the copper pots in his mother’s kitchen—Pinin would draw or sketch the cars he had seen at Alessio’s, and sometimes he would fantasize about the possibilities of designing his own car and then sketch his thoughts.

By 1910, Giovanni had acquired considerable experience of horse and horseless vehicles at Alessio’s and that year he left to start up his own Carrozzeria with brothers Carlo and Pinin. The latter was only 17 and the new company, named Stabilimenti Farina, enabled him to meet and mix with all the top automotive and racing men in Torino: Lancia, Wagner, Nazzaro, Cagno and many others.

Soon he was put in charge of publicity and design and it wasn’t long before Fiat themselves came knocking on the door asking for a design for their upcoming new car, the Zero. After many proposals, the final choice was narrowed down to two; one was from Fiat and the other was Pinin’s. Fiat boss Agnelli himself asked Farina which one he would choose and the young man replied “Mine, because I designed it!” And, as in all great stories, the Fiat man was impressed enough to take it on. So impressed was he, that he later gave Pinin a torpedo-bodied Zero as a mark of his appreciation.

Once the First World War was over, Pinin went on a mass-production techniques fact-finding tour of the USA. While there, although he absorbed what was going on to the extent that much of his future work would be highly influenced by it. During a further visit in 1952, he was offered a job by Ford that he turned down with the reason that he preferred the idea of continuing to be based in Torino.

Pinin was turning out to be something of an enigma. Contemporaries described him as being outwardly modest and unassuming, but in fact he had tremendous drive and was totally unequivocal, leading him to consider going his own way by the end of the 1920s. This would not have been as easy as it sounds as there was no financial umbrella under which he could shelter if he did this—despite the Farina company being family-owned. If he broke away, it would be entirely up to him whether a new project would sink or swim.

The break came in 1930. This was not entirely wishful thinking for Pinin as Lancia had promised him that if he started his own business, then the legendary Torinese manufacturer would guarantee him work. There was also some money forthcoming through his wife Rosa’s side of the family. So, Carrozzeria Pinin Farina was set up in Torino at Corso Trapani 107, and within the year he was at work designing a Lancia DiLambda for the Queen of Romania. Even at this early stage in his career, Pinin was being referred to in Auto Italiana magazine as “the insuperable master builder.”

Vincenzo Lancia was as good as his word and, being an innovator too, the two men started a partnership that continued on from that of Pinin’s brother. This close arrangement lasted until 1955 when Lancia was bought out by cement magnate Carlo Pesenti, but was to continue later.

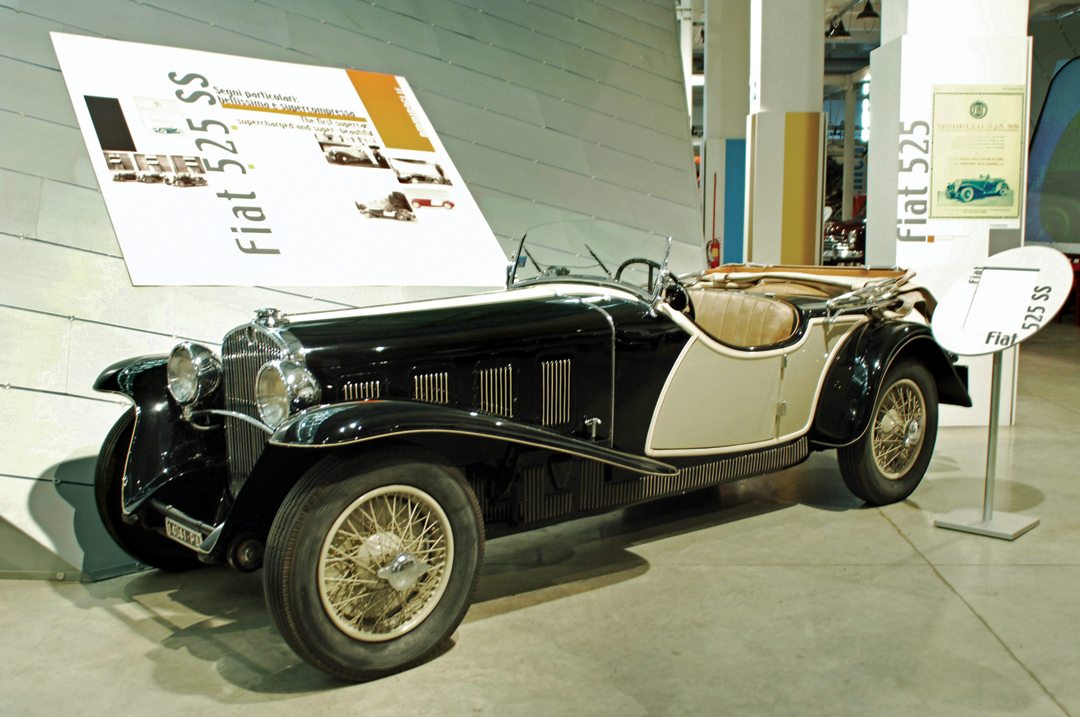

Photo: Courtesy RM Auctions

The new company started with 90 employees and took on Franco Martinengo from Stabilimenti Farina as its first styling director. He is on record as saying that in those formative years, the shape of any car was usually controlled by the height of the radiator. This tended to influence all the rest. It wasn’t until lower and wider radiator concepts were introduced that Pinin’s men were able to strike out in so many different styles. From the days when Lancias were the company’s staple diet, there were soon many manufacturers keen to have Pinin lay his hands on one of their chassis and to breathe upon it his magic. From big cars such as Isotta Fraschini down to small Fiat 1100s, before the war he was very happy to allow his designs to show American influence from such as Cord, Studebaker and Buick. A first toe-in-the-water exercise in racing aerodynamics was undertaken on the chassis of a 1937 Lancia Aprilia for the Mille Miglia. Although its lines were drawn entirely freehand, when it was much later subjected to wind-tunnel tests it was found that those lines were nearly perfect.

It cannot be stressed too highly how important the many competitive pre- (and post-) war Concours d’Elegances were to Pinin, and how important and useful it was for his cars to win these events. Nowadays we have Pebble Beach, Amelia Island, Het Loo and Villa d’Este, but then there was a never-ending succession of Concours everywhere and in all seasons. To win them increased Pinin’s standing throughout the automotive industry and marketplace.

Most industrial sites in Torino—along with Milano—were devastated during the hostilities of war and car production of any sort was but a flicker in 1946-’47, even compared to the modest numbers of 1938.

Remarkably, Italy’s economy and appetite for cars, once established, increased exponentially and continued throughout the 1950s and ‘60s at a prodigious rate. Partly this was because the pre-war base point in the country was very low compared to other European countries, so it had a lot of catching-up to do. A perfect example of this is the way the entry for early ‘50s Mille Miglias exploded to over 500 cars as young men finally managed to get their hands on Topolinos or any form of four-wheeled motorized transport and felt they had to enter.

And Pinin Farina was there to help manufacturers make the most of the situation, clothing anything, including the most mundane transport, in fabulous concepts to help excite the public who had increasing amounts of spare cash in their pockets.

It was the establishment of Cisitalia in 1947 that gave not only Pinin Farina, but the whole Italian Carrozzeria industry, the necessary kick and impetus to start to show the world the pre-eminence of Italian car design, especially that from Torino. The gorgeous little coupe that Pinin penned for them forged a place forever in the history of the motor car. It can truly be said to be the first-ever GT car, and Pinin Farina continued to refine the idea and shape through the 1948 Maserati A6 1500, the forgotten 1949 Fiat 1100S and probably even more forgotten 1951 Rolls Royce Silver Dawn Due Porte to the epochal Lancia Aurelia B20, also of 1951. A Cisitalia 202 was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1951 as part of a show entitled “Eight Automobiles,” and was described in the program by Arthur Drexler as “rolling sculpture.”

Pinin’s determination had shown through as early as 1946 when the Paris Motor Show of that year was not prepared to display Italian manufacturers’ wares, so Pinin simply set up his own show in the street outside the main show gates. In 1952 he made another important visit to the USA and came back with contracts from Nash to build the Nash Healey Spider—based on an English floorpan and American engine—and later several sedans for mass production. This U.S. connection was to stand the company in good stead for decades to come.

Perhaps the most enduring and profitable relationship Pinin was to be involved in also arose that year at the Paris show in the form of a cabriolet. It was based on the 212 Inter chassis from Ferrari in Maranello and the “partnership” survives as strong as ever to this day with the 599 Fiorano, California and 458 Italia models. This relationship became more than one of company interaction. It is reported that when Enzo Ferrari departed after one of their meetings, Pinin would stand to attention and give a little bow.

Complete body designs to high-volume manufacturers started in 1953 with the stylish Peugeot 403 saloon and continued with Alfa Romeo and the Giulietta Spider of ’55 and the British Motor Corporation Austin A40 of ’58 and later middleweight A60. It had become clear to Pinin that the only way forward for the company, and to allow for expansion, was to embrace full industrialization to allow for increased production, and in 1958 this led to a move out of Torino to a spacious, modern factory in Grugliasco.

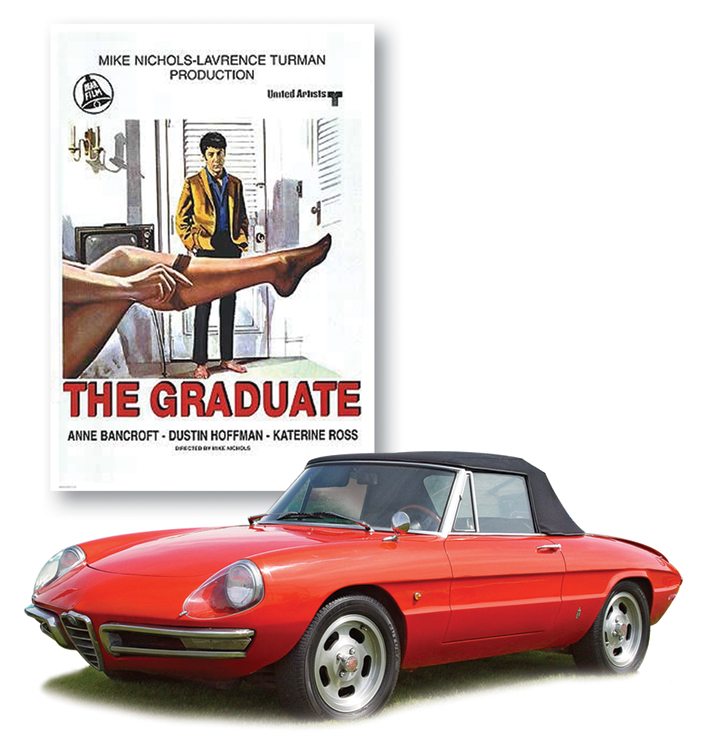

By then there were nearly 1,000 employees, and by 1960 output exceeded 11,000 car bodies. In 1961 the family changed its name by deed poll to Pininfarina, with the company duly renamed Carrozzeria Pininfarina as well. From this period, perhaps the Alfa Romeo Duetto of 1966, as featured in the hit film The Graduate with Dustin Hoffman will immortalize Pininfarina’s lines in the minds of many.

Sergio, one of Pinin’s sons became the General Manager of the new factory in 1961 and on April 7, 1966, Pinin died. Sergio then became Chairman, and Renzo Carli took up the post of Chief Executive. The connection with Lancia had endured, and Pinin had used the prototype Lancia Florida (to materialize as the Flaminia) as his own road car right up to the time of his death.

Chief designer Aldo Bravaraone was joined by Leonardo Fioravanti, who was taken on in 1967 and became responsible for many of the best-known Pininfarina projects and, in fact, took control of Pininfarina Studi and Ricerche in January 1982, at a new location in Cambiano, 20 kilometers from Torino, after it was split off from Industrie Pininfarina.

Fioravanti, along with Antonello Cogotti, had also been responsible for the establishment of an in-house wind tunnel in 1972, and in 1980 the 50th anniversary of the company was celebrated with the construction of the Ferrari Pinin.

This was a four-door sedan Ferrari powered by a flat-12 as used in the 512. Although Enzo was sympathetic to the concept and was interested in the possibility of producing it, Gianni Agnelli said no, because he thought a sedan did not fit in with the Prancing Horse’s image.

A new factory was built in the 1980s to accommodate the courageous Cadillac Allante project by which Pininfarina designed and built a lavish coupe in Torino and the shells were airlifted, 56 at a time, to Detroit for final finishing.

It is easily possible to fill a book with just the most important car concepts and projects that the company has produced over the years but, as Pinin realized all those years ago, it was necessary to industrialize and expand frontiers to survive, and Pininfarina has done just that. In 1987 it helped design a new high-speed train for Italian Railways, and has stayed in the rail business ever since, most recently collaborating on refurbishment of the Anglo-French Eurostars. The 2006 Winter Olympics torch was designed by them, as have been trollies for the USA, and they were design consultants for Coca-Cola Freestyle.

While the motor car business has faced considerable difficulty during recent years, with many manufacturers employing their own designers with hugely variable results, the 3,000 people employed by the various Pininfarina spin-off companies around the world causes most of us to be touched, in some way or another, by the Pininfarina aesthetic today. That’s not a bad legacy for a family from rural Northern Italy, and further, this same legacy helped re-establish Italy in the forefront of world design.