For the past 65 years, Formula One motor racing teams have relentlessly chased the dream of perfection that concludes with them winning a World Championship. In the early years of the modern Grand Prix series it was the Italian Alfa Romeo, Maserati and Ferrari teams—with occasional intrusions by the German Mercedes team—that took the top honors. Spawned and led by the enigmatic Enzo Ferrari, until his death in 1988, Scuderia Ferrari has stood the test of time competing in all World Championship seasons since 1950, the inaugural year. Over those years, the much-revered Italian team has seen the very highest of successes and the nadir of abject failure, but still it strives and is adored by the zealous tifosi. In Ferrari’s instance, they haven’t depended upon others to produce their racing cars. For better or worse, the racing cars they’ve competed with have been manufactured and produced “in house,” winning their first World Championship Grand Prix at Silverstone, in 1951, when Froilan Gonzalez was first across the line. Since that day, Ferrari drivers have visited the top step of the F1 World Championship podium 224 times (as of the end of 2015 season).

Following the cessation of hostilities in WWII, Britain had a thirst to become a major player in the world of motor racing. This ambition was driven by Raymond Mays—racing driver, entrepreneur and former co-founder of English Racing Automobiles (ERA). Success would reflect favorably on the British car and engineering industries and bring prosperity to a war-torn nation. Manufacturers associated in the production of automobiles were invited to contribute to this new co-operative project, in the case of British Racing Motors (BRM), by the supply of goods and/or hard cash. Monies were put into a trust fund to finance the venture. Organized by a committee, progress and results were both slow and poor, so disillusioned support waned, leaving a shortfall of both components and finance. One of those supporters, Alfred Owen of the Rubery Owen Group of companies, eventually threw a lifeline to the ailing enterprise under the banner of a new company, the Owen Racing Organisation, which would become the financial kingpin of the BRM marque for most of its existence. The dreams and aspirations of the new team were analogous to those of Ferrari, in that ultimately they wanted to become sole manufacturers and producers of their own chassis, engine and gearbox. Alfred Owen’s business plan to recover some of his group’s investment, both cash and in kind, was for BRM eventually to sell complete cars and/or parts. History shows—for a variety of reasons—success for BRM was sporadic and sadly, in the main, disappointment became their only friend. Today, nearly 40 years after the demise of the BRM team, the legacy and romance of their ambitions and achievements are still revered far and wide, and most especially in their green and pleasant English hometown of Bourne, in Lincolnshire.

Choices

Aristotle said, “Excellence is never an accident. It is always the result of high intention, sincere effort and intelligent execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives—choice, not chance, determines your destiny.” Looking at that quote, it could be said that BRM and those steering the team always had the very highest of intentions, those who worked for BRM put in a sincere effort, and yes, there was intelligent execution, but looking at BRM’s history, some of the choices they made could be said to be questionable. For example, the poorly funded and overly complex of the initial V16 car, the involvement of Louis Stanley, Tony Rudd’s obsession with the H16 engine that nearly bankrupted the team and the lack of engine development in the latter years are just a handful of wrong choices that certainly determined their destiny.

Of course, there were better choices made that resulted in certain purple patches of team history, like the building and development of the P25. Stirling Moss considered it one of the best road holding racing cars of its era. Indeed, in the hands of Jo Bonnier, it gave the team their maiden World Championship Grand Prix victory at the 1959 Dutch GP at Zandvoort. However, it was the choice of bringing others in like Moulton, Issigonis and Chapman to reconfigure the rear suspension, Tony Rudd to make changes to the front suspension and their own Peter Berthon to make significant improvements to the engine that led to that victory. In the “make or break” year of 1962, the Tony Rudd-designed P57 was a great car that handed Graham Hill the World Championship, with the team also winning the F1 Constructors World Championship. But, 1962 became the ultimate zenith of the team’s existence. The appointment of Tony Southgate as chief designer was another inspired choice that resuscitated the ambitions of the team, as was team manager Tim Parnell’s decision not to change Beltoise’s tires in the 1972 Monaco GP, which led them to what would be the last victory ever for BRM.

Monaco 1972 and beyond

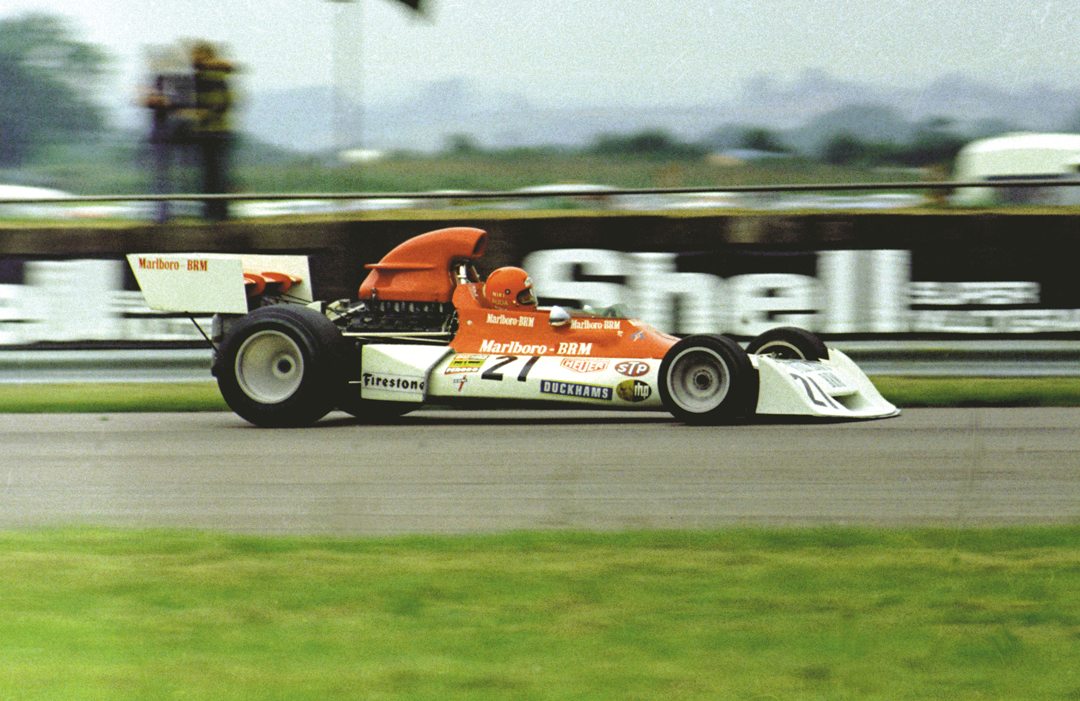

In fact, if we look at the BRM team during the 1972 Monaco GP, it was still riding reasonably high and on a crest of another wave of success. Then team manager Tim Parnell recalls that famous race around the streets of the principality: “In 1972, in our Marlboro car, we won the Monaco Grand Prix with Beltoise. I couldn’t believe it. At the time, Monaco was one of the only races televised worldwide, Marlboro was overjoyed.” He went on to praise the extreme effort made by Beltoise, “You know, Beltoise was a hell of a bloody good driver. However, he could have been a lot better if he had had two strong arms—he had a problem with them. The wet Monaco race suited his ‘condition’ as the car slid on the wet surface as he drove.” The then team designer, Tony Southgate, also extolled the driving virtues of Beltoise, “I’m not too sure of his problem, whether it was an accident, or if he was born with it, but he had limited movement in his elbow. He would have to swing his arm from his shoulder to his wrist. If you look at any BRM driven by Beltoise, you’ll see we compensated for his disability by putting an extra bulge on the right-hand side of the cockpit. This was to give him extra manoeuvrability and stop him hitting anything. As a driver, I don’t think he ever got the credit he deserved, especially driving in that race.”

Buoyed by this success, the team looked forward, but it was Louis Stanley who continued to “sell” drives in the cars that both stunted the growth and development of the team and confused the mechanics too. Southgate explains, “It was all to do with money. A lot of the extra drivers were ‘rent-a-drivers.’ They would have extra logos on the car, ‘Racing for Spain’ or similar. Louis may have thought the more cars in the race the more chance of winning, but I think it was money and prestige. Tim Parnell and I were dead against any of this. We went back to three cars, but still we had a race where not one finished. I think the engines were all tired and we needed a magic wand to wave more money to build new engines—even a revised V12 would have helped. By the end of 1972, we were being left seriously behind by the DFV brigade.”

Peter Bracewell, a BRM mechanic during that period, confirms the confusion with the number of cars entered into a race, “We, the mechanics, were just a happy band of blokes willing to do whatever we could to make the team successful. Louis Stanley, in an effort to build the finances, would sell drives in the car. Three cars in a race was reasonably manageable, but he wanted five in a race—that’s where the problems started. We had little, or very few spares, so to service five cars fully at a circuit it became a question of remembering who was in what car and remembering what we’d done in setting up and running each car.” At the end of the 1972 season, the team had slipped to 7th in the Constructors’ title table—from 2nd in 1971.

Click here to order this issue in either print or digital download format.

For the 1973 season a certain Niki Lauda joined BRM. He was both brash and opinionated, but knew what he wanted and knew how his car should be set up. Peter Bracewell explains. “Niki would come in and say change the front roll bar, or change the rear roll bar, or change the front or change the rear wing settings and go out. He’d come back in to see if his times were better—if so, the changes worked, if not he’d tell us to put everything back to where it was and try something else until he saw an improvement. On the other hand, Peter Gethin, although a great driver, would come in and say the car was oversteering, or understeering, and ask us to fix it. He didn’t really know how to set the car up.”

Photo: www.chrisbayleyautomobilia.co.uk

Mike Pilbeam re-joins BRM

At the end of the 1973 season, Ferrari had plundered Lauda and teammate Clay Reggazoni from the BRM team. Designer Tony Southgate also moved on, joining former BRM driver Jackie Oliver at Shadow. Southgate was saddened to call it a day, as he reflects, “I had enjoyed my time at BRM, and therefore was a little sad to pack it in. But, it was the end for them, history shows they declined quite rapidly from there on, although they did make some new cars. Mike Pilbeam took over chassis design. It was a team with little or no future, something that couldn’t be kept going without any great improvement.” Mike Pilbeam was no stranger to the BRM team, he’d worked for them earlier in his career during the days of Tony Rudd and the H16, but left to join Lotus and later Surtees.

With key members of the team departing, and following disagreement with Louis Stanley, Marlboro, like Yardley before, left for McLaren. With Stanley’s particularly persuasive manner and great hype for the team’s aspirations for the new season, French oil giant Motul became BRM’s new sponsor, and two new French drivers, Henri Pescarolo and François Migault, joined fellow countryman Jean-Pierre Beltoise. Pescarolo had been an F1 journeyman since 1968 driving for Matra. He’d previously enjoyed backing from Motul at Frank Williams Racing Cars during the 1971 and 1972 seasons. It was Pescarolo’s next to last chance of winning a Grand Prix, prior to full-time sportscar racing. Migault, on the other hand, was recognized as a new kid on the block with a glowing F3 background. His Grand Prix debut had been with the unfortunate Connew project in 1973, this was his chance to show bigger F1 teams exactly what he was capable of—that’s if indeed BRM had reliable enough equipment for him race.

Photo: Maureen Magee

BRM P201

Losing Lauda was a tremendous blow to the team, but inevitable once Enzo Ferrari had beckoned. It was particularly significant too for Mike Pilbeam, as the new car had been designed around Lauda, as Pilbeam confirms. “I had actually designed the car with Niki Lauda in mind as a driver, but he’d already left for Ferrari prior to completion.” Indeed, Lauda had actually sat in the cockpit prior to completion, but now all attention for the new P201 was on Jean-Pierre Beltoise. Beltoise, although in his seventh year of Grand Prix racing, was still an immensely quick driver with an appetite to win. He’d adapt his driving style to overcome any issues or problems encountered with the car, or outside interferences like the weather. Henri Pescarolo’s driving style and attitude was quite different, he’d simply persevere and drive round and round until his lap times eventually came down, although he was extremely capable.

BRM’s P201 was very different in style, design and appearance to the bulbous “coke bottle” shapes synonymous with the Southgate era, and bore a considerable resemblance to the new Gordon Murray-designed Brabham BT42 and BT44 cars. Mike Pilbeam commented on the design similarities to Murray’s Brabham, “On re-joining the team, I ran Tony Southgate’s P160 BRM for a short while. While finishing touches were put to the new car, the P201, I’d done some wind-tunnel work with the P160. It was pretty obvious that in a cornering attitude, particularly at high speed where it has a bit of a slip angle and a bit of a yaw on the vehicle, there was quite an appreciable lift directly associated to the curvy sidepods, so that’s where the triangular sides came into it. I had, indeed, tried something similar, but not as extreme, at Surtees on the TS9. John (Surtees) wasn’t too impressed as he thought the new squarer section would crash on the ground—the edges of the outer sidepod were quite close to the ground—I just took the idea a little further on the P201, but with a triangular shape rather than a square section. I can’t really remember, but I’m pretty sure the design concept for the P201 was a little before Gordon Murray’s Brabham was released. It was just one of those coincidental times when two designers arrived at the same line of thinking at the same time. Of course, like Tony Southgate, I had to make certain cockpit arrangements to accommodate Beltoise’s disabled right arm—the side panels were quite heavily sculptured to allow him to move freely. It was quite challenging for him to maneuver properly without these refinements to the cockpit.”

Photo: Maureen Magee

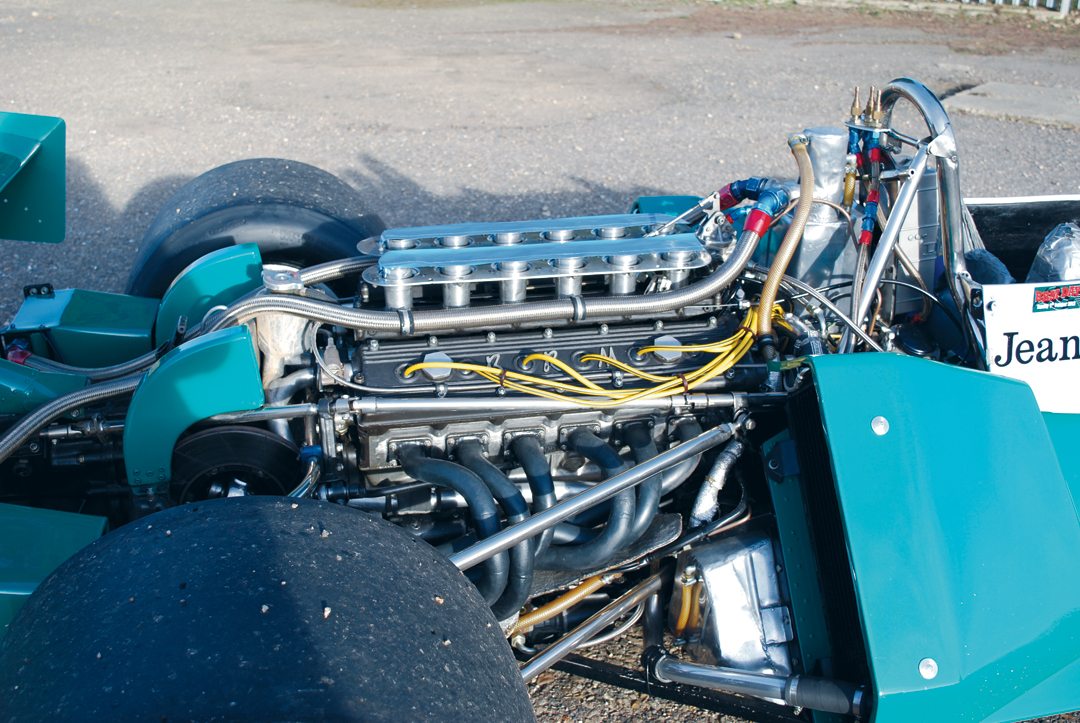

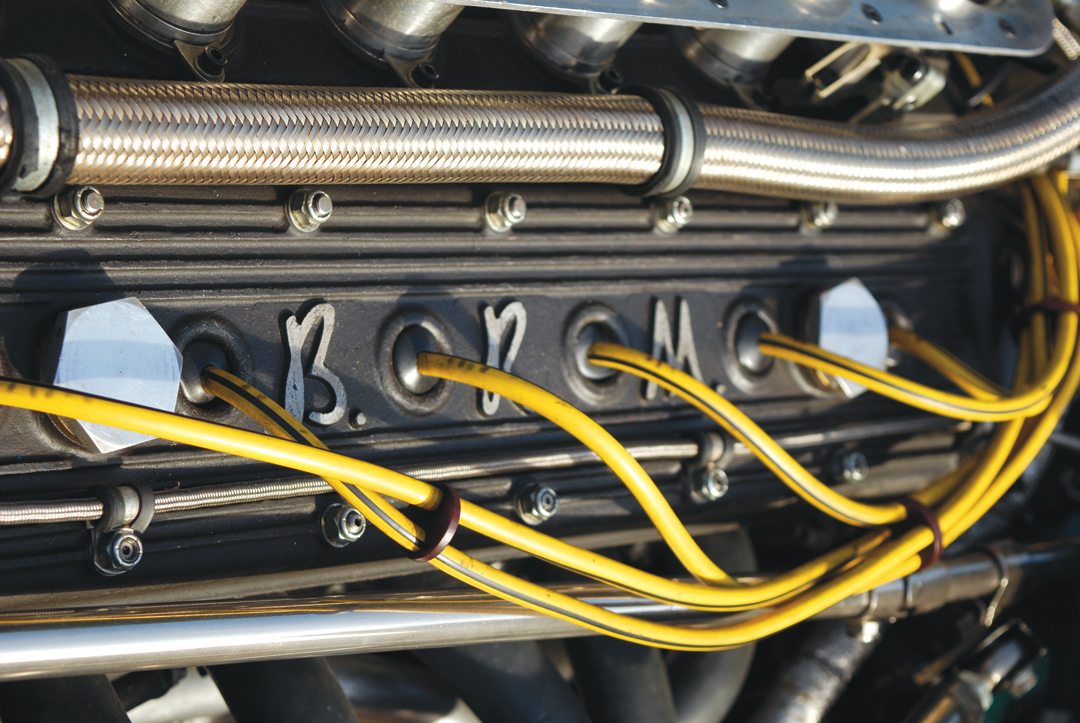

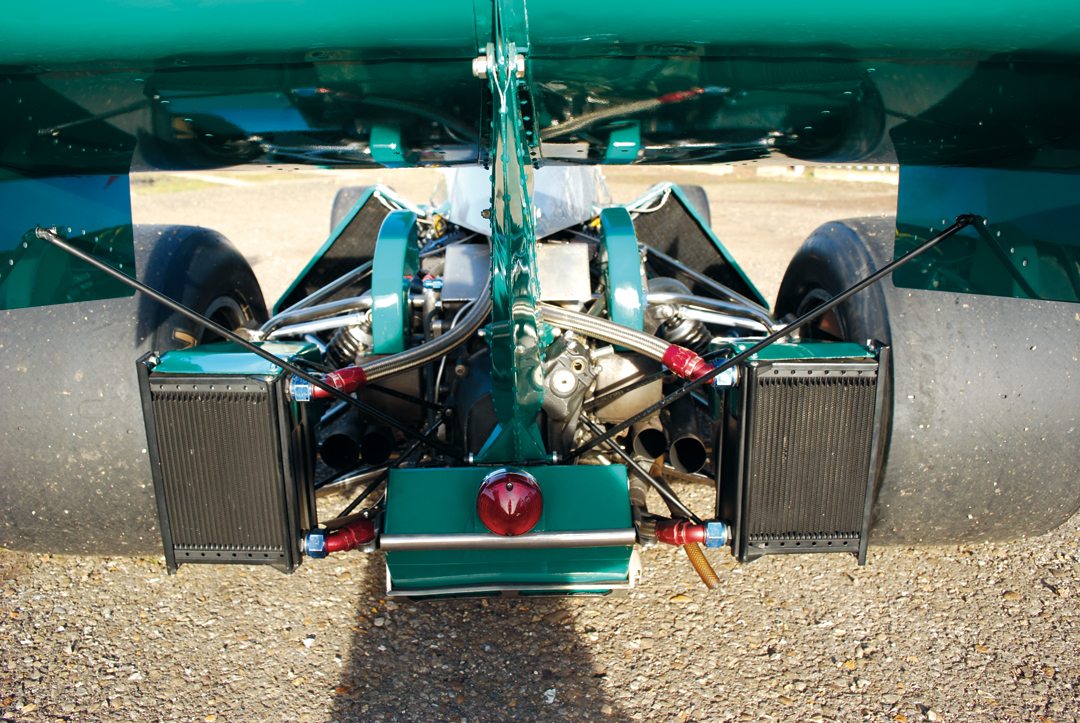

The car looked a little more compact than previous models, although both the track and wheelbase were increased in relation to the P160. It also included revised steering—lighter to maneuver, which obviously suited Beltoise—and suspension geometry to achieve better handling. Brakes, both front and rear, were inboard. As usual it was powered, using the term “powered” very loosely, by the now aging BRM P200 V12 engine. Louis Stanley reported the engine to have around 460 bhp at 11,000 rpm—on a par with the Cosworth DFV. The truth of the matter was plainly obvious when the car took to the track. Peter Bracewell explains: “The engine was the problem and, despite what Mr. Stanley would say, due to its age very much down on power in comparison to the DFV. The early races of a season would always be the best for us in those closing years, as we’d have most of the winter break to restore the engines fully with many new parts in them. As the season progressed, the engines would be rebuilt with the small supply of spares we had. From midseason onward, when funds were scarce, we’d be looking under our benches and scavenging some of the worn parts discarded from earlier rebuilds. Of course, this meant we were falling further behind on both power and reliability. It sort of sums up the team really, as mechanics we could only work and produce the best we could with the limited materials we had available.”

The first races of the 1974 season were, as usual for those days, in South America with the Argentine and Brazilian GPs. The P201 was still awaiting completion, so revised P160s were used with Beltoise, the best placed BRM driver, finishing 5th and 10th, respectively. To give a measure of the loss, Lauda and Reggazoni were 2nd and 3rd in Argentina and Reggazoni 2nd in Brazil. The debut race for the P201 was in Kyalami, South Africa. The team had run revised P160s at the opening South American events at Argentina, Beltoise was 5th, Pescarolo 9th, while young Migault retired. At Brazil, BRM didn’t fare as well, but at least all three cars finished 10th, 14th and 16th for Beltoise, Pescarolo and Migault, respectively.

Photo: Tucker Conley

BRM P201 chassis 01

In total, five P201 chassis were constructed, competing in 26 races. The first was the 1974 South African GP and the last, running in “B” spec, was at the 1977 South African GP, driven by Larry Perkins in Rotary Watches livery.

Jean-Pierre Beltoise was the first to compete in the new car, so while BRM P201 chassis 01 was for Beltoise to drive, the others had to use the upgraded P160s once again. Mike Pilbeam recalls: “We’d had a couple of hours shakedown test at Silverstone and another similar test at Ricard prior to the South African GP. We’d made minor adjustments, nothing too drastic, and looked at certain reliability issues that always crop up, but in essence the car remained much as I’d originally designed it.”

Tragedy struck in South Africa as the GP weekend was overshadowed by the dreadful loss of Peter Revson who was fatally injured at the wheel of his Shadow during practice. The Shadow team withdrew from the event as a mark of respect. This fatality followed closely that of François Cevert in October 1973, less than six months prior, at the USGP in Watkins Glen—ironically the last F1 race won by the unfortunate Revson. In qualifying, Beltoise finished 11th on the grid, while former BRM employee Lauda took pole—his first for Ferrari. In the intense heat, the race was one of attrition, with many cars falling by the wayside. By now the P201 had had the shroud covering the radiators removed. Beltoise plodded on and on, slowly making his way up the order as the new car performed well. A race reporter noted Beltoise’s driving style in that he had the presence of mind to keep out of the sweltering slipstream of cars he followed, therefore increasing a cooler airflow. Shod on used qualifying tires, the Frenchman overtook the McLaren M23s of Fittipaldi and Hulme and gained further places with the demise of both Lauda and Reggazoni in the Ferraris. Both Mike Pilbeam and Peter Bracewell agreed that the Kyalami circuit favored the Firestone better than the Goodyear tires, and it was an important ingredient in the new car finishing in 2nd place. Sadly, but inevitably, this would prove the last time a BRM driver would ever grace an F1 World Championship podium. The men from Bourne were jubilant and embraced Beltoise’s success, hoping it wasn’t to be another flash-in-the-pan result.

Race 2 for the car was the next GP on the calendar at Jarama, Spain, for the Spanish GP the curtain raiser to the European F1 season. BRM took three racing cars, the lone P201 for Beltoise and the two revised P160s for Pescarolo and Migault. Trying too hard, Beltoise lost control of his car in practice, damaging the front end, which gave the mechanics plenty of work that evening —especially as Migault had taken three corners off his 160 as well. Starting 12th on the grid, Beltoise managed just three laps in the rain-affected race before the engine—BRM’s Achilles Heel—let go, and that was his race run.

The new Nivelles-Baulers Autodrome in Belgium was the next race, just two weeks after Spain. This was only the second time the Belgian GP was run at the 2.3-mile circuit, of which drivers commented on the bland and sterile nature of the track in comparison to Spa. Despite that, Beltoise looked to be back on good form with a 7th-placed qualifying, again in the lone P201. In a reasonably uneventful race, Beltoise finished 5th in front of the McLarens of Hulme and Hailwood—the last time BRM would ever score F1 World Championship points.

The Monaco GP was the first race where Beltoise had the choice of P201/01 or the new 02 chassis. He could only manage a best time of 1m32.2s in the new car as opposed to a 1m28.1s and an 11th-place grid spot in his original car. The tight and twisty circuit of the Principality took its toll and Beltoise tangled with Hulme’s McLaren as they climbed the hill to Casino Square on the opening lap. As wheels locked together, the McLaren hit the guardrail, while Beltoise’s BRM suffered severe suspension damage. This coming together resulted in a melee that also took out Redman’s Shadow, Pace’s Surtees, Merzario’s Williams, Schenken’s Trojan and Brambilla’s March.

Photo: Pete Austin

Just two BRM cars arrived in Sweden a couple of weeks after Monte Carlo, with Beltoise again in P201/01 and Pescarolo having his first race aboard a P201, in the newer chassis 02. As Beltoise took 13th place on the grid he might have known it was to be an unlucky race—lasting just three laps before the engine expired. Pescarolo fared even worse when his car caught fire on Lap 1! BRM was back in the mire once again.

The youngster, François Migault, drove the P201/01 in the next race at Zandvoort and Beltoise P201/02—both retired with gearbox problems. Pescarolo, still in the P160 retired “officially” with handling problems, but truthfully by this time he was totally disillusioned with his position. For the following two races in France and Great Britain, Pescarolo was at the wheel of P201/01, but unfortunately, once again, the car retired with mechanical failure and an accident at Brands Hatch. It was the last time P201/01 appeared on circuit.

At the end of the 1974 Italian GP, Henri Pescarolo and François Migault left the team, with Beltoise being joined by Chris Amon, who’d campaigned his own chassis earlier in the year, for the races at Mosport, Canada, and the final race of the season at Watkins Glen. Neither Beltoise nor Amon were classified among the finishers at Mosport, but Amon finished 9th at Watkins Glen, while Beltoise was a non-qualifier for the USGP, the last Grand Prix he entered, due to a severe accident in practice that he was lucky to escape without serious injury. So, the end of the 1974 season brought the real demise of the team with the French drivers and the Motul sponsorship withdrawing, Mike Pilbeam leaving to begin a new business and Tim Parnell finding it difficult to work under Louis Stanley. As a result, Peter Bracewell and a number of other mechanics were “laid off.” Support from the Rubery Owen Group dwindled as the company fell upon hard times and Sir Alfred suffered poor health, sadly succumbing in 1975.

Photo: Mike Wilds Archive

Given this, Mrs. Jean Stanley, sister of Sir Alfred, who’d worked tirelessly in the background for so many years for the team, “officially” took complete control of the remnants of BRM. Having said that, it was her husband, Louis Stanley, who had his hands tightly on the reins. For this “new era” under new management the cars were repainted in a red, white and blue livery with the words “STANLEY-BRM” emblazoned—rebranded by many onlookers as the “Stanley Steamers” due to the times the engines blew up! Aubrey Woods took responsibility for the entire development of the car and just a handful of other staff, including Alan Challis, remained. Mike Wilds drove the P201 in the first two races of 1975. Although Bob Evans, Ian Ashley and Larry Perkins were to drive it after that, Mike’s candid recollections sum up the whole situation, which can be read in this issue’s “Legends Speak” column. It shows how Louis Stanley would take hard cash from American, French and Swiss companies to finance the race team, but also his intransigence at the thought of testing a Cosworth engine in the back of the P201—made in the UK, but financed by Ford—a suggestion that cost Mike Wilds his job. If Gordon Murray and Mike Pilbeam were on the same lines with racecar design at this stage, it’s hard to understand why BRM couldn’t see that the Cosworth-powered Brabham was more competitive in 1974 and 1975, with five wins from 26 races in total, and 2nd place in the Constructors Championship in 1975.

Photo: Paul Kooyman

Driving the BRM P201’01

The scavenged remains of P201/1 together with P201/2 were sold off during the latter part of the 1970s to Arthur Carter, and resold again to Mike Burtt in the 1980s. With the blessing of Rubery Owen, chassis P201/2 was rebuilt and so, subsequently, was P201/1, although by this time a new monocoque was required. Since the 1990s, it has been demonstrated and successfully competed at many historic festivals and events. Indeed, the car was taken to France and driven by its original pilot, Jean-Pierre Beltoise, during this period too.

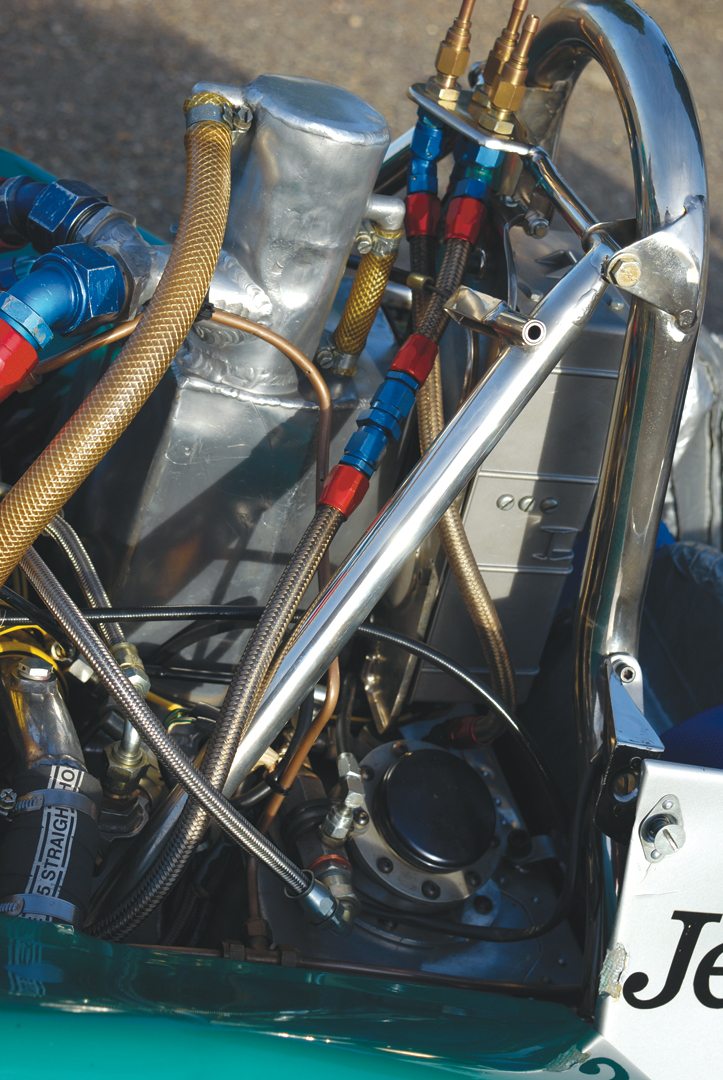

Today, it is resplendently turned out and was rebuilt in Bourne by former BRM mechanic Rick Hall’s restoration business. The car today looks the epitome of first class engineering, which indeed those mechanics and fabricators who produced the original cars did. In period, the team seemed to take a considerable amount of jibes and abuse from the motoring press, mainly due to the arrogance of Louis Stanley who, undoubtedly at the time the team became rebadged Stanley-BRM, thought he was England’s answer to Enzo Ferrari. Certainly, those I’ve spoken to who worked for BRM in those latter days feel a little hard done by, especially having to keep three cars racing at all the events, which meant them working very long hours and sometimes all through the night. Those men were a dedicated band producing some of the finest engineering seen in Formula One racing.

Photo: Hall and Hall Archive

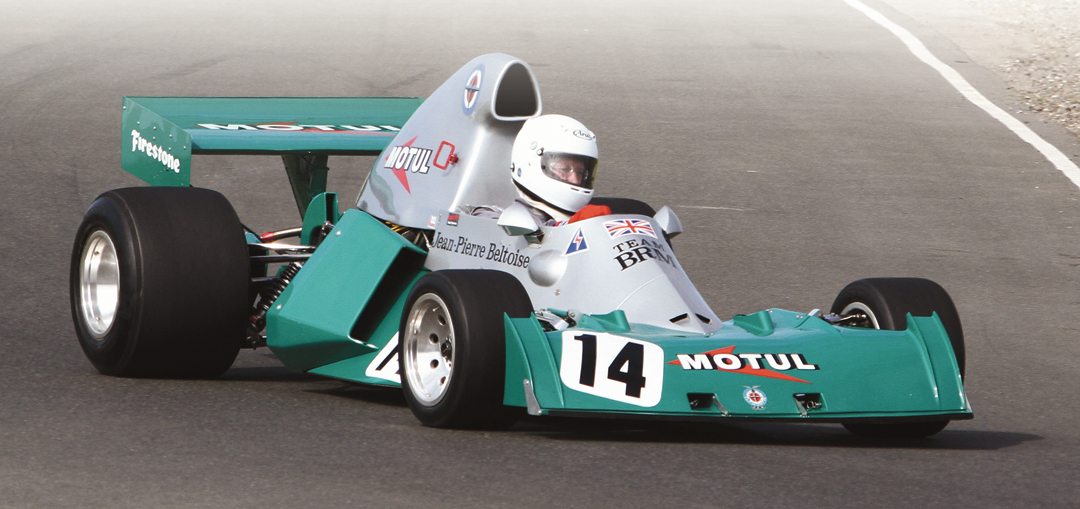

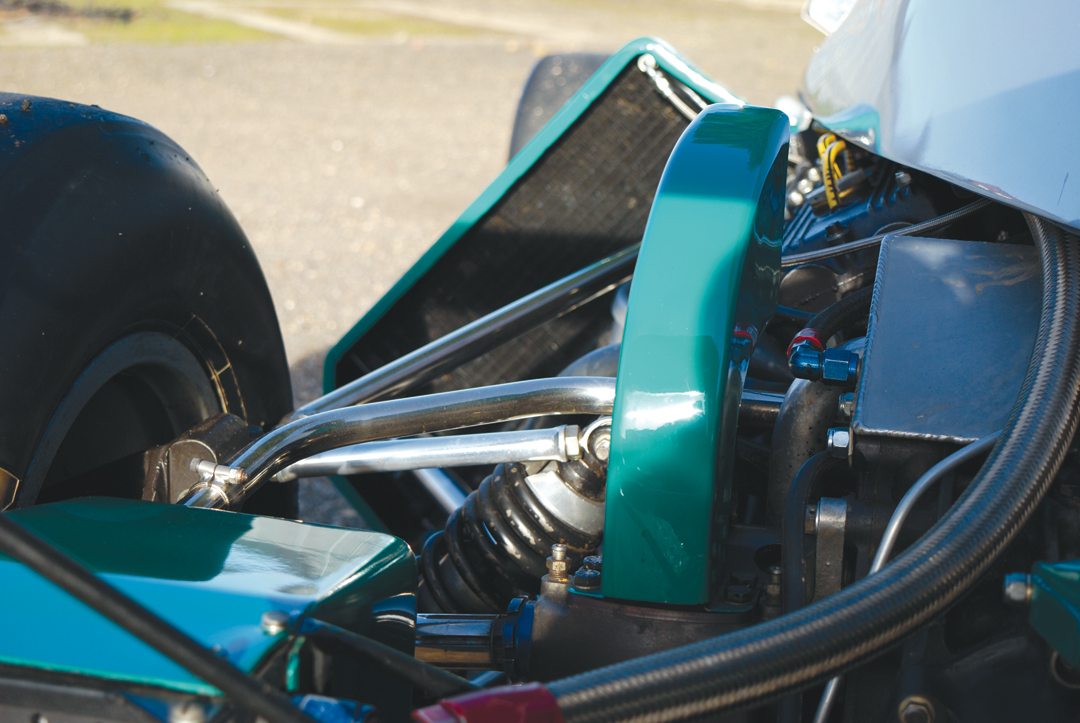

The car is back in original Motul sponsored livery with silver on the air-box and top surfaces and green sides, including the unique saddle-type radiator covers. The lines are sleek and purposeful and the car looks like a top contender of its day—although history tells a different story. Today, we are to test the car at a track in the home county of BRM, Lincolnshire. Blyton Park is a former RAF base, on the edge of the rural village of Blyton, and situated 70 miles north of Bourne, the former home of British Racing Motors. It was opened in 1942, and was the Operational Training Unit for Polish aircrews learning to fly Wellington bombers. This disused airfield, closed in 1954, has now had those concrete runways and surfaces fully tarmacked and since 2011 has operated as a driving center and testing facility. The 1.43-mile outer circuit is not your conventional racetrack in that, with just a small grandstand, the likely spectators are native four-legged wildlife and various ornithological visitors flying aloft. It’s fully open to the elements, and although on the chilly side, thankfully the sun is shining and the compact track is dry. The car has been thoroughly prepared and warmed up with water at 60-degrees, fuel pressure between 115-120 poundbs and oil pressure at the required limit too. The car is ready to go out on circuit, but will need a couple of laps to get the tires and brakes to operational temperatures. The front brakes have been put outside, rather than the original inboard position. Originally, the inboard units were of cast magnesium, but following Beltoise’s 2nd place at Kyalami the team noticed a crack in the unit, from then on they used fabricated brake discs and caliper mounts.

Comfortably sat and belted in the reasonably spacious cockpit, behind the steering wheel on the dash is a centrally positioned rev counter with its tell-tale red line set at 9,000. To the left is the dual water and oil temperature gauge, and to the right the fuel and oil pressure gauge. Now, it’s time for the type 202 V12 engine to burst into a wonderfully deafening roar. After the tires and brakes are warmed, we’re ready for a more purposeful lap, grabbing second and ensuring the revs are kept up, we enter and exit the tight left-hand Twickers bend. Accelerating up to fourth gear as we approach a tricky third gear, off camber left into Jochen, exiting we’re immediately on the next right and down to second for The Ump, this leads to a smooth left that opens into Lancaster where we can take full advantage and unwind some of the V12 power on the fastest part of the circuit, hitting near maximum revs in fifth gear. Above 6,000 rpm the power really comes on and the car responds appropriately, very well balanced, light to control and very forgiving. As we approach the Wiggler chicane it’s braking down to third, killing the speed for a slow in, fast out, left-right-left and back up to fifth before Bishops, a deceptive left-hand corner that looks tighter then it really is, taken in third. Exiting Bishops is the double apex corner Bunga Bunga. The first part of the corner is in third, but as the second apex tightens it’s down another gear. We’re soon back “on it” and approaching Port Froid that can be taken quite fast as long as the car is positioned correctly, it’s an adrenaline-charged smooth chicane that can be straight-lined. On to the last corner, Ushers—a small rise and fall undulation on this otherwise flat circuit—taken in third and then we’re back to Twickers a tight left which on our much faster entry is easy to understeer.

Given the experience of driving, the chassis, brakes and steering were all positive, giving a lie to the poor results and unreliability the car had in period. However, the V12 power unit has been meticulously prepared and is music to the ears of any enthusiast, it didn’t miss a beat. Up against the might of the V8 DFVs in period, the BRM V12, although less powerful and with less torque, would have given a good account of itself—as it usually did in practice. Serving with the team as he did at the time, Rick Hall said, “The press were constantly on our backs, unfairly in my opinion. They had no idea of the work that went into producing the cars, or the quality either. When the cars and engines were all new they could live with them all—DFVs, the lot. I wrote to Autosport journalist Alan Henry at the time saying that he should look at the grids. There were more Cosworths behind us than were in front, but my letter was never published. We were the only team out there, other than Ferrari that made everything. We needed some support in our hour of need, but didn’t get it.”

Today’s historic racing is a platform where the car can finally show some of the anticipated success it should have had when first unveiled. It may not have won a championship—although in the hands of Niki Lauda, who knows?—but the car could have had a better history written, if only the bumptious and bungling Louis Stanley had listened to his mechanics and drivers and given them the opportunity to develop a more reliable engine.

Click here to order this issue in either print or digital download format.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Aluminum monocoque

Engine: 2998-cc BRM P200 V12 – injection

Transmission: BRM 5-speed manual gearbox

Suspension: Double wishbones, coil springs, dampers

Tires:Avon (Firestone period)

Brakes: Ventilated discs all around

Steering: Rack and pinion

Power: 450 bhp

Wheelbase: 102 inches

Front-track: 60 inches

Rear-track: 60 inches

Weight: 1,290 pounds

Resources/Acknowledgements

Grand Prix—Race by race account of the F1 World Championship – Mike Lang

A-Z of Formula Racing Cars – David Hodges

Directory of Formula One Cars 1966-1986 – Anthony Pritchard

BRM – Raymond Mays and Peter Roberts

Grand Prix Who’s Who – Steve Small

Periodicals: Motor Sport, Autosport

Sincere thanks to Rick and Rob Hall and the team at Hall & Hall for help with the car and background information.

Thanks also to Mike Pilbeam, designer of the car, Peter Bracewell, team mechanic, and Mike Wilds, driver, for their recollections of period life with BRM.