Click here to read Part 1 of Something Special

One of the chief complaints about early sports racers is that they cost too much, with RS Porsches, Jaguar D-Types and Ferraris going for $500K to over $1 million. Here are some suggestions that will get you into vintage sports racer groups on considerably less budget. It’s simple – buy American!

In the last issue we took a look at some great cars that carried the stars and stripes in 1950s sports car racing. This month we’ll pick up a few more classic sports racers that were actually built to sell to customers, as opposed to one-offs or purely factory-supported entries.

JABRO

In 1957, James Broadwell, of St. Louis started his line of H-Modified racing cars by purchasing a 1949 Crosley sedan for $50. He spent the next seven months fabricating a simple space-frame chassis from 1-1/4” diameter 17-gauge TV antenna masts. This tubing was chosen for its reasonable cost and low carbon content, which made it easy to weld. Split front axles were used, similar to early Lotus 11 and Mallock practice. Fabricated kingpin ends mounted Crosley spindles, and a standard Crosley rear axle was used, with spacers that extended the track to 44”. A Crosley torque tube was shortened and took the power from a modified Crosley engine and MG TD transmission. Brakes were Goodyear Hawley sport disc brakes with dual master cylinders. The attractive body (looking like a 3/4 scale D-Jaguar) was designed by Broadwell and cast in fiberglass. The first car was built for less than $750, and was named the Jabro Jr.

Broadwell soon put two models into production. To keep costs down, the base model Jabro Mk.I used Crosley suspension at front and back and either sport or drum brakes. A set of instructions and drawings to build your own chassis was $5 with a frame running $345 and a body $290. Total weight of a finished Mk.I was under 850 pounds.

The Jabro Mk.II was identical to the prototype and featured split front axles. The Mk.II could also be purchased in plan or kit form, with the revised chassis going for $595, complete with suspension. The bodies were very similar with the Mk.II having three vents added below the belt line and a wraparound windscreen. The door cutouts were accentuated to make it look more like a Lister-Jag.

In 1961, Broadwell introduced the Mk.III, which was sold in a variety of configurations. Initially, it was a front-engined design with offset driveline and a “birdcage”-style frame of 3/8” diameter tubes. The same split front axle suspension was used, and the engine choices were Crosley or Mercury outboard boat engines converted to automotive use. The Crosley torque tube had been replaced by a conventional live rear axle and coil springs. This chassis cost $695. For those who did not want the complexity of this type of chassis construction, a conventional space frame version was available for $100 less.

One Mk.III was converted to mid-engine configuration by a friend of Broadwell, and soon this version was available directly from Jabro. Still confusingly called a Mk.III, it had the same front suspension, but a rear end based on a Fiat 600 transaxle and rear suspension (although at least one was built with a VW transaxle). Engine choices included Crosley, Mercury or the SAAB 3-banger.

Although Broadwell did not sell turnkey cars, he sold many speed parts to help the home builder. He designed several head conversions for the Crosley engine. The first, modified it from twin ports to Siamesed ports for improved flow, while the later Mk.III head was a cross-flow design with four intake and exhaust ports. Jabro also revised the cooling system and adapted Dell’Orto carbs to fit. The cross-flow conversion cost $245, and a full-race 65-hp (@ 9,000 rpm!) engine was $850. Jabro would also sell any of its bodies for use on other chassis, so not every “Jabro” special has Jabro running gear.

A fair number of Jabros were built, particularly the Mk.I model. Although most were originally Crosley powered, many were re-engined over the years with SAAB or even BMC engines. I have seen rough examples sell recently for as little as $2,500, but expect to pay in the $10,000+ range for very nice examples, particularly the rare and quick Mk.III.

KELLISON

Californian Jim Kellison was a former fighter pilot who built his first kit car in 1959. There were initially four body styles, the J2 roadsters that fit a 102” wheelbase, while the popular J-4 coupe was a few inches shorter. Smaller K-2 roadster and K-3 coupes were intended for even shorter foreign car chassis. The J-4 coupe was an attractive fastback design that stood only 38” tall. In addition to selling these fiberglass bodies, Kellison offered several chassis kits as well as turnkey cars. His first chassis was designed by Chuck Manning, who had built winning racecars of his own. It had live axles at both ends and weighed a paltry 140 pounds. Later rectangular-tube chassis used Chevrolet sedan, Corvette or Dodge torsion bar suspension. Kellison sold bodies for $365 to $600, with chassis adding $650 to the bill. Kellison also sold plan sets for building replicas of his chassis.

The prototype Chevy-powered coupe was raced by Andy Porterfield in 1959, but it was not properly prepared and unsuccessful. A number were raced on a club level, and Kellison coupe bodies were also used on Bonneville and drag cars. In 1963 and 1964 the fastest sports car at Bonneville was Nolan White’s Kellison K-2-bodied Chevy road burner that was clocked at 224.477 mph!

In the mid-1960s Kellison production was taken over by Allied Fiberglass, who renamed the line Astra. They carried on the same body and chassis kits and added a higher-roofed model called the X-300GT. Both Astra and Kellison sold lightweight racing shells that were thinner than their street bodies, with optional headrests on roadster models. Production continued into the early 1970s. Several Kellisons have been run in vintage racing and in “touring” events like the Colorado Grand.

Kellisons are relatively plentiful, and unfinished examples with factory frames are selling for less than $5,000 (bare bodies for a fifth of that). Completed cars on a variety of chassis sell in the $5,000 to $20,000 range. Check with your local race group, but most clubs will accept a Kellison built with all-period equipment, particularly with a provenance. Try one on for size first, as the coupes can be pretty cramped. The most common engine choices were Chevy small blocks, Pontiac 389s and various sized Ford FE models.

OL’ YALLER

Much has been written about the legendary mongrels built by Max Balchowsky in Hollywood, California, in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Max’s personal cars, Old Yaller I and II, were fantastically successful on the West Coast, driven by the top talents of the era. However, Max had to earn a living, and he also built a number of cars for private entrants.

Max started building hot rods in the early 1950s, including a stunning ’32 Ford roadster with a Buick “nailhead” V-8. Max raced it in Cal Club races through 1955 and began swapping domestic V-8s, usually Buicks, into various imported sports cars. He particularly liked the Doretti, an attractive English sports car based on Triumph running gear. Max shoehorned a six-carb Buick into one and took it racing. It was successful enough to inspire a short production run, probably less than 10 cars. One of these would be a real find, as long as it hasn’t been “restored” by a well-meaning Anglophile.

Old Yaller I was built out of the Morgenson special, a Plymouth-powered homebuilt, but Max replaced the engine with his traditional Buick and modified the frame. This car was very successful, giving Max a formidable reputation in West Coast racing circles. He sold this car to Eric Hauser and built Old Yaller II, which was entirely his own design. With its huge grill and front clamshell fenders, it lacked in aesthetics but was fully competitive on the track.

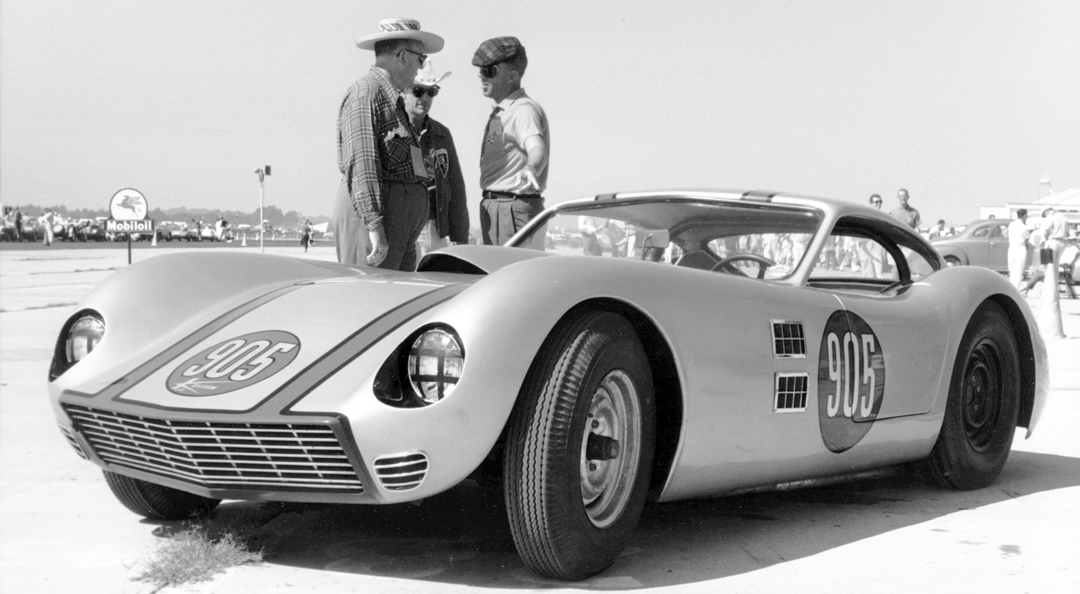

Photo: Bob Tronolone

With Old Yaller III, Max set down a basic formula for customer-version race cars. They had space frame chassis set up for a Detroit V-8 with steel or wire wheels. A Jaguar gearbox was usually specified, and the double A-arm front suspension was a mixture of Jaguar (upper arm) and Pontiac (lower arm) parts. A modified Studebaker Champion live axle was used with a locked spool differential. Torsion bar suspension borrowed from the Morris Minor was fitted all around. Jaguar disc brakes lived up front with Buick Alfin drums in the back. Customer Old Yallers had 91” or longer wheelbases and weighed about 1,900 pounds. The price for a complete chassis, less body, gearbox and master cylinders was $3,500 in 1960.

Although Max had made his reputation with ugly, if purposeful, race cars, he knew the customer cars must be better looking. Troutman and Barnes made a run of handsome aluminum bodies for $2,000 each. Old Yaller IV was similar to III, but number V was a “special” for Dave MacDonald and his sponsor Jim Simpson. The chassis was stretched to 92”, and a fuel-injected 327” Chevy was installed. Pontiac and Buick Alfin drum brakes were used all around. A pseudo-1961 Corvette body was made up (17” shorter than stock), and the rear axle was swapped to a Chevy II. This car became known as the MacDonald Corvette and it was successful on a club level in 1962, but was outclassed in national events. This jem is in hiding, although Max said a few years back it had been in Hawaii at one point.

Max reverted to his standard formula for number VI, but number VII was equipped with a fiberglass body and a Chevy V-8. It was rebodied with another fiberglass unit after an accident. This car is currently active in vintage racing. Mk.VIII was originally intended as a street car for Hollywood cinematographer Harold Wexler, who had sponsored Max’s racing efforts. It was built on a Jaguar XKE monocoque, with fabricated suspension and Buick drum brakes all around. A Chevy V-8 was used and California Metal Shaping made a one-off aluminum nose. Reportedly, Wexler was terrified of the car and it was soon sold. Later, it was rebodied by renowned stylist Dean Jeffries, and Lola T-70 wheels were installed. Old Yaller VIII has since been restored to original condition and is actively raced in vintage events.

Number IX was the last car built and resembled the earlier customer cars. It appeared in a number of movies, including Spinout with Elvis Presley and The Love Bug. The final race for number IX was in 1966, when Max and Bob Drake finished 15th in the Stardust USRRC race in Las Vegas, then drove it home to California. Most of the Old Yallers are currently running in vintage racing, with a few tantalizingly not accounted for. Old Yallers are among the most sought-after of American sports-racers and three have changed hands over the last five years. The last one I know about sold in the low six-figures and in today’s market, I would guess that would be a reasonable starting point. (See pg 47 of this month’s Market Guide for Ol’ Yaller VII on offer)

Photo: Allen Kuhn

KURTIS

Frank Kurtis “owned” Indy car racing from 1950 to 1955. His Los Angeles shop turned out strong, reliable cars that would stand up to the banging and beating of serious circle track racing and could be maintained in the field by privateer teams. So when he decided to try his hand at sports racing cars, he followed basically the same formula.

Earlier Kurtis sports cars had been boulevard cruisers, with his first series taken over by Earl “Madman” Muntz and revised into the Muntz Jet. Although these were not intended for racing, some owners tried and they were competent dry lakes cars. The first Kurtis design, intended for sports car racing, was the 1953 500KK chassis kit. Kurtis had taken note of the popularity of the first fiberglass kit car bodies. Most, like the Glasspar G-2, Woodill Wildfire, Byers SR-100 and Sorrell, were designed to fit on prewar Ford chassis with Ford flathead V-8 running gear. Some had tubular chassis made by the Mameco Company that retained the Ford suspension. Although a few were raced, they lacked the handling and brakes to take on an XK-120, much less Ferraris and Allards.

Kurtis reasoned that a chassis based on his 500A Indy car would be a better starting point for kit construction than an old Ford sedan. The Kurtis 500KK chassis was available in wheelbase lengths from 92” to 100”, with traditional Kurtis live axles at each end. Springing was by torsion bars, trailing at the front and leading at the rear. Brakes were up to the buyer and most opted for Ford drums. A variety of bodies were placed on 500KK chassis, including Byers, Sorrell, Atlas (a Cisitalia replica), Bangert and a few custom-made aluminum jobs. Engines ranged from hot-rodded GMC sixes to DeSoto hemis and Mercury flatheads.

For those who preferred turnkey racers, Kurtis built the 500S. This had essentially the same chassis as the 500KK and was sold in a variety of wheelbases. The aluminum bodies featured a shark-like toothed grill with a cigar-shaped body sporting cycle fenders. The obvious inspiration was the Allard J2, but the Kurtis handled much better. Although one of the first cars finished was powered by a Hudson six, most were fitted with hotter iron. Bill Stroppe notched up an impressive record on the West Coast in his Mercury flathead-powered version. Bill Murphy had a 500S with a DeSoto hemi, but later replaced it with a Buick.

By 1955, the 500S was getting long in the tooth, outmatched by the latest from Italy and England. Kurtis introduced the 500X, which used the same basic live-axle suspension as the 500S, but with a more sophisticated space frame chassis, 200 pounds less weight and a bulbous aluminum body. Reportedly, 10 were built, with the most successful being Bill Murphy’s Buick-powered bomb. The first six were sold in completed form, the rest as kits. Jack Hinkle had the first car built (he and Murphy were partners with Kurtis) and installed a 1500cc Offenhauser to take on the OSCAs in the Midwest. It was later re-engined with a Chevy V-8. Mickey Thompson had one with a Pontiac mill, Ak Miller preferred FoMoCo power, and Texan Bob Schroeder raced one with Bowtie muscle.

One of the lesser-known Kurtis models was the 500M, a street version of the 500S package, with a somewhat bulky full-fendered fiberglass body. The inner panels were steel, which made the 500M more civilized, if heavier, than the earlier model. Although originally intended to have a Ford 4-cylinder industrial engine, most were fitted with a variety of V-8 engines. Primarily intended for street use, they were occasionally raced. Bob Schroeder ran a Buick-powered 500M in Texas and Mexico, and Bob Christie raced one with a Nash engine in Mexico as well. About 20 were built before Kurtis shut down his sports car operation in 1955.

In 1962, Kurtis took one last stab at sports cars with the Aguila, another Indy car variation but with removable outer body panels, so it could be run as a sports car or, sans fenders, in the proposed Formula 366 series intended for domestic V-8s. A Chevy-powered example was raced by Herb Stelter in Texas, another ended up as a dragster for Sam Perriot. The third (and last) was fitted with a streamlined body and raced successfully at Bonneville by Jack Lufkin. That was it…by the early 1960s, live axles were old news and Stelter’s car was only run on a club level. It has been actively campaigned in vintage racing by George Shelley, and the Perriot dragster is in a museum in City of Industry, California.

Approximately 35 to 40 500S and KK models were built, and they remain rare and valuable today. Expect to pay from $125,000 to $150,000 for a 500S, although 500KK models are sometimes available for under $20,000 in rough condition with less attractive period-kit bodywork. However, pretty examples (like the Byers and Atlas bodies), with proper provenance, can command close to 500S money.

Kurtis chassis are very basic and therefore easy to duplicate so check the provenance carefully. Also, since Kurtis was state of the art in the early 1950s, many specials were built at that time with similar specifications and are easily mistaken for Kurtis chassis.

In the early 1990s, Arlen Kurtis, Frank’s son, began selling new 500S continuation models that were almost identical to the originals. Twelve chassis were built and some are still available in the $75,000 to $85,000 range.

In 1990, Jon Ward bought some chassis units from Arlen Kurtis and fitted them with modern brakes, engines and componentry for the Carrera Panamericana, which he won in 1991. He sold his race cars as well as some copies, but be aware that some clubs do not recognize these, so check your regulations first.

The 500X models are very rare and only about three survive. Since they and the Aguilas do not come up for sale on a regular basis, it would be impossible to set a value.

The 500M is a bit of a bargain if you like the vaguely Thunderbird-like appearance. There were two on the market as we went to press, one for $8,000 in rough rolling-chassis condition and the other at $30,000+ for a nice driver.

MULTIPLEX

While most American racing cars of the early 1950s were intended for big V-8 power, Multiplex chose to concentrate on the 1500cc class. Although this Berwick, Pennsylvania, company had built a handful of cars from 1912 to 1913, its principal work was industrial machinery. In 1953, they introduced the Multiplex 186, a sports car designed by former stock car and dirt track driver “Fritz” Bingaman.

The prototype showed some original thinking, with a space-frame chassis featuring a sheet steel backbone tunnel similar to the later Lotus Elan. Front suspension was by upper A-arms and a lower transverse leaf spring that also acted as the lower suspension link. Monroe 50/50 shocks were used and the geometry was adjusted to keep the wheels upright at all times. Goodyear 5.90-15 tires were used on perforated steel wheels. A Ross box was used for steering with a quick two turns from lock to lock. Rear suspension was conventional practice, with a Borg-Warner live axle hung from parallel leaf springs. Wheelbase was 85”, with a total weight of 1,925 pounds distributed 52% front, 48% rear.

Multiplex wanted to keep the car all-American and initially experimented with a modified air-cooled Harley Davidson 74 2-cylinder motorcycle engine, but reverted to an English Singer 1500cc mill for the competition debut. In September 1953, the light-blue prototype, with an uninspired slab-sided aluminum body, showed up for an AAA race at Floyd Bennet Field in New York. Driven by Henry Fanelli, it put on a good show in the under 1500cc class, running as high as third to an OSCA and Jim Pauley’s Bandini before losing a wheel. However, the Multiplex had outdistanced a potent field of Porsches, MG specials and two Siata V-8s (and this was with a stock Singer engine!). Fanelli also drove the car at Turner AFB in Albany, Georgia, for the final AAA race of the year, but OSCAs continued their class domination.

Encouraged by their potential, two more Multiplex prototypes were built for a production run. The body on the first car did not receive kind attention from the press, and fiberglass copies of the Cisitalia Grand Sport coupe and roadster were substituted (a number of companies made these bodies, including Atlas Fiber-Glass and Allied Fiber-Glass in California). The roadster was to have a modified Willys 4-cylinder engine producing 87 hp, while the coupe was treated to a 161” Willys six. The six was optional in the roadster as well. But according to The Standard Catalog of American Cars 1946-1975, only the three prototypes were built. Multiplex offered bare chassis as well, so it is possible more escaped before the ax fell in 1954. Setting a value on a marque this rare is difficult, although a Multiplex would probably sell for about the same as a comparable special (approximately $8,000 – $30,000, depending on condition and provenance).

Photo: US Air Force