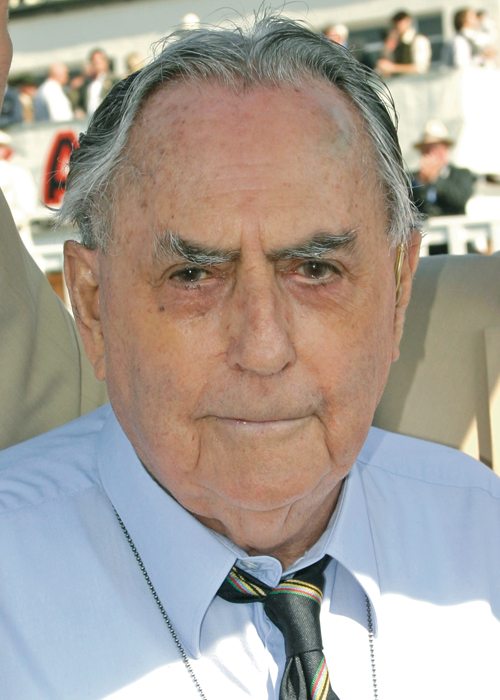

Photo: Roger Dixon

As a tribute to triple World Champion Sir Jack Brabham, the only man ever to win the World Championship in a car carrying his name, we offer this previously unpublished interview that the Australian icon gave to VR’s European Editor Mike Jiggle in which he discusses his decision to build his own Grand Prix cars, and then how he came to drive one to his third World Championship. With Brabham’s mid-May passing, we present it for you here as a way to honor his remarkably full life and the exceptional accomplishments of his career.

A few years ago my wife and I had the pleasure of having lunch with Sir Jack and Lady Brabham at their favourite hotel in Weybridge, England. Jack was a straight forward man and didn’t understand the concept of a club sandwich. To him, a ham sandwich was a piece of ham between two pieces of bread – end of! Despite Lady Margaret chastising him about his behaviour, he persisted to ask the waitress about the fayre she had brought to him – a ham club sandwich. He asked for another plate and the waitress obliged. He asked her what the oily stuff was dripping from his sandwich. “Dressing” she replied. “Well I like my salad like I like my women – undressed!” he replied to the now blushing waitress. He completely deconstructed his club sandwich and made what he really wanted – a piece of ham between two pieces of bread. Lunch was truly eventful.

When Formula One returned to power in 1966 with the new three-liter engines, doubling the size of the previous 1500-cc power plants, was that the reason you left Cooper?

Brabham: Cooper wasn’t going anywhere, really. Poor old Charlie didn’t want to go forward. I’d always wanted to build my own car anyway…the first car I ever raced I built myself. It was just time to do it all over again.

When the three-liter formula was announced, some teams were uncertain how to handle all the power. What were your thoughts?

Brabham: Yes, four-wheel-drive was looked at by some. It had already been done by Ferguson some years earlier. The problem with three-liters, everyone thought it was going to make Grand Prix racing far too expensive. Four-wheel-drive was never an option for me, although many went along that route just a few years later. Coventry Climax had lost interest in racing and they were on their knees by that time anyway, their 1500-cc engine wasn’t that good, either. I think they just lost interest.[pullquote]“I’d always wanted to build my own car anyway…the first car I ever raced I built myself. It was just time to do it all over again.”[/pullquote]

The new regulations also allowed supercharged and turbocharged engines, why didn’t anyone take that option?

Brabham: We certainly weren’t interested in that side of it, no one else thought about it either—I’m not sure why. A normally aspirated engine, for me, was a good way to go, and all others went that way too.

There was another concern with the power-to-weight ratio, a high-powered engine in a very light chassis?

Brabham: Yes, in other forms of racing where the power-to-weight ratio was high, we’d seen many accidents. I think that’s why the turbo and supercharged engines weren’t used at that time, people were a little hesitant about how safe they’d be, particularly with turbos, as you’d have no power one minute and far more than you could handle the next.

How did you decide to have Repco produce your engines?

Brabham: Well, we wanted a three-liter engine and we’d obviously had a little bit of warning about the changes. I happened to be in the Tasman series, so I asked them if they would be interested in building the engine for me. They went for it, they said they’d love to do it. As time was getting on, I suggested they use an Oldsmobile cylinder block to start with, and we’d build the engine around that. We could take time to build a proper block later. So, that’s the way it happened. I went to America and got hold of a block. Actually, I’d first decided on a Buick block, but fortunately the guy in the GM engine shop was a bit of a racer and said it would be better to use Oldsmobile.

Many teams went along differing routes with engine supply and design. What did you make of the BRM H16?

Brabham: There was really no need to make things so complicated. Unfortunately, BRM started a lot more races than they finished.

Among the other teams, Cooper went to Maserati and Bruce McLaren went to Ford. What did you make of that?

Brabham: The Maserati was an old engine, they were looking for power. The Ford engine wasn’t that good, it had very big ports and really didn’t work. It suffered from very poor throttle control, as well. The American idea of a powerful engine was a lot different to our understanding of a powerful engine. I remember going to Indy with Repco, we were based at the Champion facility. Mickey Thompson, the land speed record holder, came to have a look at our car, as they couldn’t believe how well it was going. He huddled around the engine with a couple of his friends, I heard him say, “Just think what we could do with something like this.” He was amazed.

Dan Gurney used the Weslake engine in his Eagle.

Brabham: Yes, a very nice little car, too. He made a good job of it, the only problem for him was that I ended up World Champion instead of him!

If we look at the season race by race, you didn’t finish too well in South Africa (non-championship race), although you had pole and fastest lap?

Brabham: No, we had a few problems. One was with a little cog belt that drove the distributor; that broke and we were finished. We made modifications after that, but it was a good test run for us anyway, it showed we had something going for us, which we could build on.

The next time out was the International Trophy Race at Silverstone. The first victory for you in the new Brabham-Repco.

Brabham: That was good…the first time is always good.

What were your feelings as you prepared for Monaco, the first round of the 1966 World Championship?

Brabham: The car was quite good, I think we started on the middle row, or thereabouts, but the engine threw a rod before I’d even left the line. I remember giving it a big burst and then bang! In our first three-liter engines, we were using Daimler con rods, and that’s what broke, the Daimler con rod. From then on we made our own and never had a bit of trouble with them. I suppose we’d tried to do it on the cheap using Daimler parts. It doesn’t always work.

Spa was next, a difficult track where local weather systems come into play. Wasn’t it a very wet race with a very big accident at the start?

Brabham: Yes, there was a huge accident at the start. In those days, the organizers had to make a decision whether to start us on dry tires or wet tires. At the time, the decision was made it was dry, so we all started on dry tires. Partway through the first lap, we came over a hill and as we went down the other side at the Masta Kink the road was soaking wet. I was so bloody lucky, I was sliding across the road and heading straight for a house—I thought I was going to go straight in there. Luckily, I caught a concrete curb, which stopped me going straight off. I kept going, the next lap around I saw half a dozen cars had gone off. Spa was a dangerous place to race, especially if the track was wet, and especially in those days. Jackie Stewart had a particularly bad crash ending up in someone’s back garden. You can’t believe how bad it was.

I took the lead in the race, but had to pit for some tires so went down the order a bit. I think we finished 4th. Changing tires then isn’t like it is today, not even “knock-off” wheels. It took some time and I lost track position.

It was due to that crash that Jackie Stewart started his safety campaign. What did you think about his work?

Brabham: Jackie did a great job. He was the right man. I couldn’t do much as I had a team to run, he was just a driver. He certainly made a difference. Some liked it, some didn’t. Less people were killed after he’d started, so it was a great thing for the sport. No one wants to die racing. Louis Stanley did a good job too, with the mobile Medical Unit, they didn’t go to all races though—mainly all the European rounds. It’s a shame that the Medical Unit wasn’t about in later years, we may have saved a few more people.

Talking about accidents, which one of the drivers lost had the biggest impact upon you?

Brabham: Losing Jimmy (Clark) was real bad, I think it really affected me. You didn’t expect it from Clark. He was a very close and good friend, as well. We just couldn’t believe it. It was just a puncture. Unfortunately, Jimmy didn’t have a lot of feel for the car. Months before that, in a Formula Two race at Rouen, we were having a big dice. During the race, I noticed Jimmy’s back tire was going down, I think everyone noticed—except Jimmy. He never backed off, he was going full chat and the tire was going down. He was one of those racers who didn’t care what the car was doing, he’d fight it to get it back under control.

In this race, we got to a stage where we were about to go through the Esses, I knew there was no way Jimmy would make it, so I backed off. I thought he would have an accident on his own. He made the first corner, but lost it on the second one. He went off and hit the rails. There were cars in front of me, which got through, but as Jimmy bounced back onto the track he hit me. It’s the first time, I’ve backed off, taken it easy and still had an accident. Jimmy just didn’t have a feel for a car, sadly that’s what happened at Hockenheim.

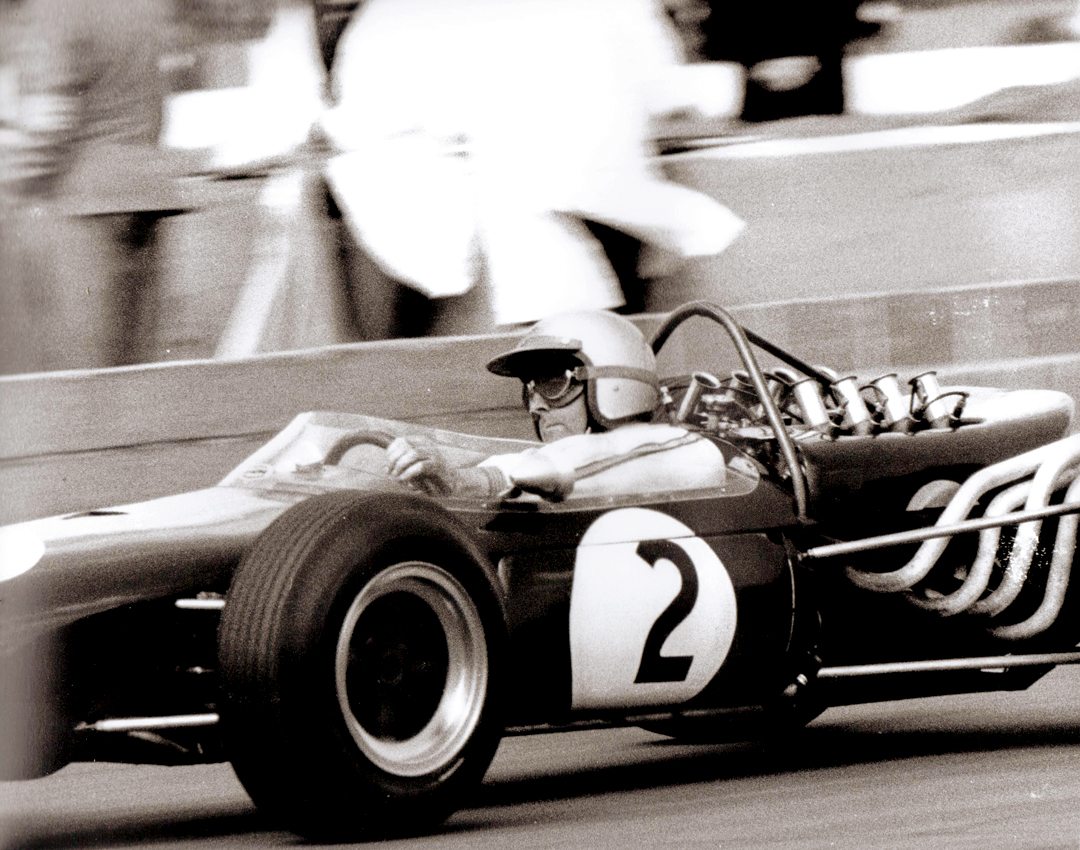

Reims was next, the place where Jack Brabham made history. What was it like winning a World Championship race in your own car?

Brabham: That was a big thrill too. Ferrari had had a lot of pre-publicity saying how they were going to win the race, that Reims was their circuit. I thought if I could beat Ferrari on “their own” circuit it would be extra special. I got more enjoyment out of that race than anything else. They had Lorenzo Bandini and Mike Parkes. Mike was a good driver, but I managed to down them. I think he finished 2nd and Denny Hulme brought the other Brabham in 3rd—the first race he’d had a Repco engine. It was great to beat them on a fast circuit. Many people, including Ferrari, thought they couldn’t be beaten on a fast circuit.

We ran in Formula Two that weekend too—both me and Denny. The Formula Two cars had Honda engines, they weren’t that great that first year, 1965, as they were just normal production engines. The problems were around the fuel injectors and things like that. At the end of the year, they built us a new engine for the 1966 season. So, not only did we win the Formula One race, but the Formula Two race as well.

I was one of the development teams for Goodyear—it was their first win at Reims with me, too. We went home with a couple of hundred bottles of champagne—a great weekend!

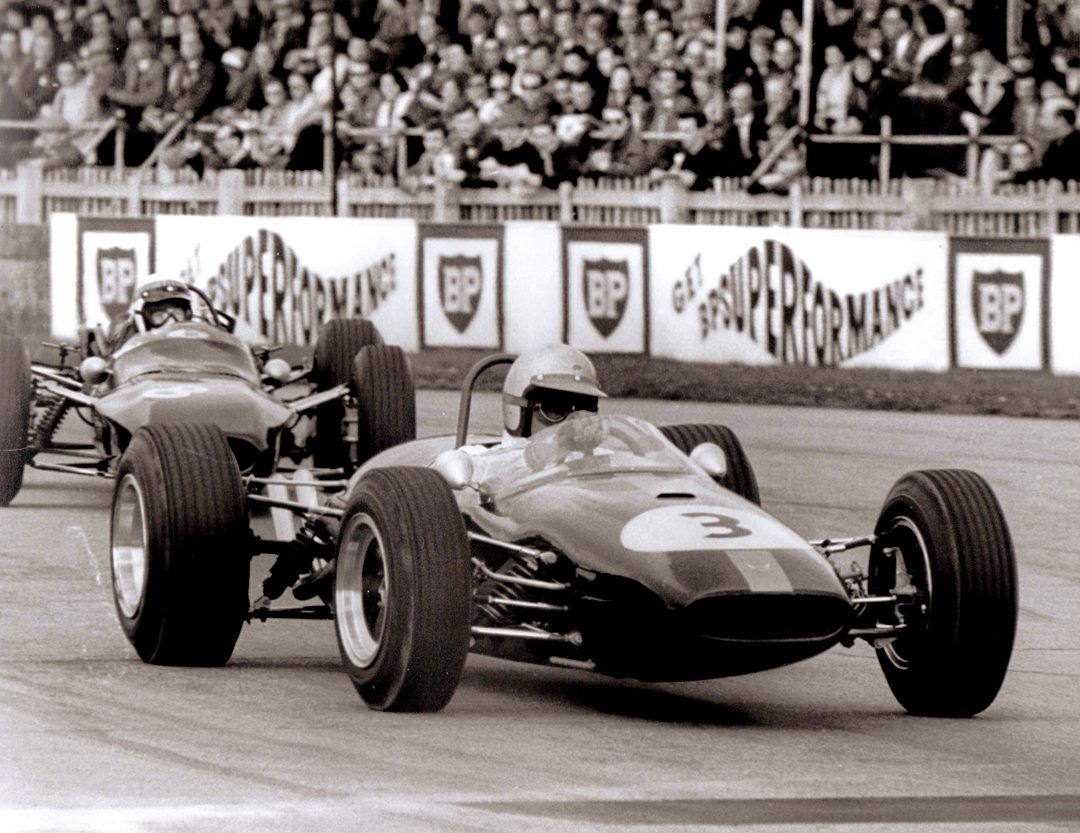

At Brands Hatch for the the British GP, after such a great weekend in France, were you pretty “pumped up” for that race?

Brabham: The car was extremely good, both on long, fast circuits and shorter, twisty circuits, the Repco engine had a good torque curve too. All round it was just an easy car to drive, a good handling car, as well. The British GP was our first 1-2, Denny finished 2nd. I couldn’t believe we were doing so well.

I loved racing at Brand Hatch. It’s a small circuit, but what I’d call a driver’s circuit. I’ve had some smashing scraps there, wonderful racing and just a fantastic circuit to drive. To drive on the limit at Brands, for an entire race, was quite a difficult thing to do, but very rewarding and gives a sense of satisfaction. To win there was just fantastic, it gave me quite a lift to do that.

Then came the Dutch GP at Zandvoort, what problems does the sand cause—especially on a dry, windy day?

Brabham: It made it a bit tricky around some parts of the circuit, it just depended on which way the wind was blowing. It didn’t affect me at all that I can remember, just gave us something else to cope with.

If the Brabham car was to be tested, wasn’t the Nürburgring, the next stop for the Grand Prix circus, the place to test it?

Brabham: It was wet, too. So, to win there was a great thrill for me. I don’t think anyone goes to the Nürburgring and wins first time out. It takes several goes to do that. Luckily, I’d raced there several times before and could probably say I knew my way around it—I’d got it taped. Flying lessons were another thing you needed, we took off at certain sections of the circuit. It made you concentrate, the landing was always very important. The car leaving the road was one thing, getting back was another, there was a danger it could shoot you right off. The secret was to have the wheels pointing just in the right direction.

You said that Reims was a Ferrari track, so the race at Monza was a chance to beat them at home, but it wasn’t to be, was it?

Brabham: No, but I had to give them a chance, otherwise they may have gone away and left Formula One altogether! I remember racing in 1958, with the Cooper, and we used the Monza banking. What a frightening thing, so much so, we told them if they were to use the banking in 1959 we’d simply not race. The surface was just concrete slabs, some were up and some down; it rattled and vibrated the car. You’d hear a bloody great bang and the suspension would fall to pieces—unbelievable to expect cars to race on it. You just couldn’t race on it.

After Monza wasn’t it then across the pond to Watkins Glen for the penultimate race of the season?

Brabham: We had a new batch of cam followers just prior to that meeting, made by Alfa Romeo. For some reason or other there was two or three cast iron ones among them. Unfortunately, my mechanic who was doing the engine put a cast iron cam follower in the engine and that was it.

We only had four mechanics, two for each car. Roy Billington, Ian Lees, Bob Village—he was the engine man actually—and Ron Dennis. Ron Dennis was a fantastic organizer. He’d always got the transporters organized alright, all the spare parts and that sort of thing. Today, each team goes to a Grand Prix with an army of men for this and that—hospitality too. For me, I’d mechanic all night on the car and just for a bit of relaxation I’d drive it in the race!

What was your relationship like with Denny Hulme?

Brabham: Yes, he was a good bloke, a great driver, he did well for us. He was a New Zealander who became part of the family. We got on very well.

The final race of the season was at Mexico, problems there?

Brabham: If I remember rightly, they had to start the race about an hour late. Pedro Rodriguez had to go around the track and ask the fans to move back off the road—they were sitting on the track. They moved and we started, but after about a couple of laps into the race they were back on the side of the road again—brave people, or stupid! Seriously, it put you off of driving. We could have easily run over their feet, no joke; completely ridiculous.

Didn’t you finish 2nd, and the championship was yours?

Brabham: I didn’t take the win, I was worried about all those feet I might run over. Just before the race we had to change the engine in my racecar as it had lost compression, so rather than try and fix it we just switched it. It took about an hour and a half.

We look at the cost of running a championship-winning team these days as being a multi-million-pound cost, what was the cost for you that year?

Brabham: We ran two cars, I think we entered 12 races that year (including the non-championship races) and I think our budget was £100,000. That wouldn’t pay for the catering corps these days!

Looking back, what was the high point of that season?

Brabham: It has to be the French Grand Prix at Reims, an all-Australian-built car, driven by an Australian, and then winning my third World Championship for Australia.

Photo: BRDC

Footage from the 1966 season was used in the film Grand Prix, did you get involved with the filming?

Brabham: I first got involved with motor racing film making with The Green Helmet, we would sit around for three days and do nothing. They would ask you to do stupid shit over and over. Frankenheimer was much the same with the Grand Prix movie. He asked me to go to Monza to film some action shots. Again, three days of doing nothing. I told him I was off, so he rushed around and did my bit in about half an hour. The thing they don’t realize, is we have a job to do. I can’t spend time sitting around. I thought the whole thing was pretty stupid; we had camera cars running in the race—dangerous too. We lived with it though. I think most of us thought if they were making a motor racing film they’d better make it the best they can, so we put up with things we wouldn’t have normally done. We made sure they got what they wanted, but when we were there it was on our terms. The problem was, to film makers, the film is the most important thing. To racing drivers racing is the most important thing. We couldn’t really live together, but we made the best of what we had.

John Frankenheimer was a decent bloke, he just couldn’t understand why we didn’t think his film was as important as he did. I think we thought the film might inspire interest in Grand Prix racing, and motor racing as a whole. Sitting for three days doing nothing wasn’t my kind of fun!

All these years later, how do you look at your achievement?

Brabham: Well, pleased I lived to tell the tale. Many of the blokes I raced with lost their lives. I survived, so I think being a survivor, especially during that period of racing, means a lot to me.